George Barbier fashioned the roaring twenties — in the uneasy afterglow of one war and the encroaching shadow of another, when Paris refused to dull. It shimmered—defiantly, deliriously—as though light itself were a champagne bubble trying to escape the glass. The Jazz Age didn’t simply arrive; it erupted, blaring from brass horns, stitched into dropped waists, and inked across the pages of fashion journals. In that maelstrom of reinvention and ritualized opulence stood George Barbier: not a witness, but a conjurer.

Barbier's work was less mirror than spell. His lines—clean yet lavish—reanimated centuries of aesthetic tradition through the electric prism of Art Deco. Each illustration was a deliberate incantation: a ballet of color, classical restraint unhooked by fantasy, silhouettes stolen from antiquity and draped in modern mischief. Barbier’s genius was not in depicting an era, but in embalming its fever dreams in pigment and pochoir, so that even now, we can hear the rustle of satin in his paper salons and the pulse of freedom in his liberated forms.

Picture the curtain just before it rises—perfumed silence, breath held. That’s the atmosphere Barbier captured again and again: the moment before the spectacle becomes memory.

Key Takeaways

A Life Steeped in Art Deco: Born in 1882 in Nantes, George Barbier epitomized the modern glamour of the interwar years, emerging as one of France’s most important illustrators who deftly combined classical art with Art Deco sensibilities.

The ‘Chevalier du Bracelet’ and His Circle: During a pivotal 1911 exhibition in Paris, Barbier gained swift acclaim. He soon joined an elite group dubbed The Knights of the Bracelet, helping define the elegant lines and vibrant colors that would captivate the 1920s.

World War I’s Aftermath and Artistic Rebirth: In the optimistic frenzy after the Great War, Barbier’s rich pochoir prints and sumptuous designs met a craving for luxury and spectacle, shaping how the era’s fashion, ballet, and literature were visually recorded.

From couture to Cabaret: Barbier’s influence went far beyond the page: he crafted costumes for the Ballets Russes, stage designs for Folies Bergère, and even styled Rudolph Valentino for a silent film, sealing his reputation as a consummate Art Deco visionary.

Enduring Legacy: Although he died young in 1932, Barbier’s masterful blend of exotic influences, classical references, and modern flair continues to mesmerize historians, fashion devotees, and art lovers, reminding us that true style transcends time.

Nantes, London, and the Alchemy of Early Influences

![]()

George Barbier, La Merveilleuse au Palais Royal (1921)

A Youth Bound for the Capital

George Barbier was born in Nantes in 1882—a city etched by the salt of Atlantic winds and the quiet theatre of global trade. In its port, ships whispered of distant empires, and in its galleries, provincial patrons glimpsed the flickering promise of Paris. Barbier absorbed both: the wanderlust and the rigor. He carried this dual inheritance into the École des Beaux-Arts in 1907, where under Jean-Paul Laurens, he learned the reverent discipline of academic draftsmanship. He did not just study Ingres and Watteau—he inhaled them. He traced their gestures until his own lines could whisper with the same nuance, the same implied world.

Even then, Barbier’s canvases shimmered with more than historical mimicry. There was already something libidinous in his restraint, something ornate hiding behind the veil of neoclassical poise. Local commissions from Nantes revealed a student whose talent exceeded his age—and whose appetite exceeded his training.

An English Sojourn & Beardsley’s Spell

Then came London, and everything became silhouette and shadow. The English illustrators were a different breed—visionaries who fused the grotesque with the lyrical. Blake, Ricketts, Doré, Rackham, and, above all, Aubrey Beardsley: the monochrome magician of decadence. Beardsley’s influence hit Barbier like a thunderclap. From him, Barbier borrowed not just the ornamental curve or theatrical flourish—but the license to transgress. His palette remained lush, but his lines grew bolder, unafraid to cut the page like a knife.

It’s said he Anglicized his name from Georges to George during this sojourn—a quiet metamorphosis, as if to mark this new skin he’d slipped into. It’s apocryphal, perhaps, but fitting. London had carved its initials into him.

The Louvre Beckons

Returning to France, Barbier became a fixture at the Louvre, haunting its antiquity halls like a devoted apostle. There, amid Hellenic torsos, Persian ornament, and Japanese screens, he stitched together a worldview as eclectic as it was precise. Each civilization offered him a lens—through which beauty could be abstracted, gender reimagined, and costume transformed into cultural dialogue.

These weren’t references. They were building blocks. The Etruscans gave him contour, Egypt gave him narrative stillness, Persia gave him motif. From Japan came restraint; from Greece, lyricism. Barbier didn’t choose between tradition and modernity—he hybridized them, quietly drafting the blueprints for what would become Art Deco: a fusion aesthetic of east, west, past, and next.

The Spark of Modernity: Barbier and the Birth of Art Deco

George Barbier, Laissez-moi-feule! (1919)

1911—A Debut in Paris

In 1911, Paris saw a new kind of debut—not in the salons or on the runway, but in the incandescent walls of Galerie Boutet de Monvel. George Barbier stepped from anonymity into sudden reverence. His illustrations—meticulously constructed, riotously colored—did not pander. They seduced. Critics, disarmed by their discipline, succumbed to their decorative hedonism. With this first showing, Barbier announced his refusal to separate elegance from intellect, or pleasure from precision.

Soon, he was enveloped into a rarefied tribe: a coterie of aesthetes known as Les Chevaliers du Bracelet—a name bestowed by Vogue with equal parts irony and awe. They were illustrators, yes, but also dandies, costume sorcerers, and social provocateurs. Their bracelets weren’t just accessories—they were declarations of allegiance to beauty, artifice, and flamboyant self-invention. Pierre Brissaud, Paul Iribe, Georges Lepape—they each played their part in this decadent pantheon. But Barbier’s vision was the flame they gathered around.

He took the lush curvature of Art Nouveau and caged it inside Art Deco’s geometry. His work moved with the confidence of a blade wrapped in silk.

Cartier and La Femme avec une Panthère Noire

Even before the 1920s roared, Barbier’s flair had caught the eye of haute couture’s high priestesses. In 1911, Jeanne Paquin—a couturier known for her theatricality—commissioned Barbier to bring her designs to life. By 1914, Cartier followed, seeking an image to define the maison’s mythos.

Barbier delivered La femme avec une panthère noire—a vision of sublime contradiction. A woman in a Paul Poiret gown, Grecian in bearing, poised beside a jet-black panther. Here, femininity was strength. Elegance had claws. Exoticism met restraint. This image would become Cartier’s totem, its spirit animal: fearless, poised, predatory.

Barbier had drawn not just a woman, but an archetype.

Euphoria After War

When the cannons fell silent in 1918, Europe exhaled—but not with relief, with appetite. The world had seen its own ruin and now demanded excess, spectacle, distraction. In Paris, beauty became survival. The old order had collapsed; the new one wore rouge, clutched pearls, and danced into the night. Art Deco emerged like a phoenix wearing lacquered heels and embroidered silk. In this new vocabulary of form—hard angles made lush, symmetry made decadent—George Barbier spoke with a native tongue.

His pochoir prints did not soothe. They shimmered. Rich with gouache and ambition, they caught the light like a champagne coupe, refracting a thirst that could never be quenched. And for a culture scorched by austerity, Barbier’s images were more than pretty diversions—they were blueprints for a world re-enchanted.

Fashioning the Roaring Twenties: Ink, Pochoir, and the “Modern Woman”

![]()

George Barbier, Le Jeu des Graces (1922)

The Ascendancy of Magazine Illustration

Barbier’s art did not hide in galleries; it paraded through the pages of France’s most coveted fashion journals. In Gazette du Bon Ton—published from 1912 to 1925—his pochoirs were not mere illustrations, but visual editorials, each a couture aria. These hand-colored images mimicked the luminosity of paintings, giving fashion the gravitas of fine art. But Barbier didn’t stop at the image—he wrote, too, dissecting the subtle drama of fabric, silhouette, and gesture. His pen was as sharp as his brush.

He also contributed to Journal des Dames et des Modes (1912–1914), which chronicled Parisian society with exquisite poise—until war shuttered its pages. Barbier’s early entries there offered a glimpse of a city on the verge: decadent, daring, and dancing too close to the edge.

Poiret’s Liberation

At the same time, Paul Poiret was dismantling the female silhouette. He banished the corset, uncaged the body, and set fashion ablaze with Orientalist flair. Barbier became his visual echo. His illustrations didn't merely flatter Poiret’s designs—they enacted them. With bold sweeps of ink and riotous color, Barbier conjured a new female archetype: sleek, self-possessed, in motion. She wasn’t waiting in a drawing room. She was halfway out the door, laughing.

In Print and Beyond

The list of magazines and almanacs bearing Barbier’s touch reads like a symphony of desire: Les Feuillets d’art (1919–1922), Art Gout Beauté (1920–1933), Vogue, Femina, La Vie Parisienne. And beyond them: fashion albums like Modes et manières d’aujourd’hui, La Guirlande des Mois, Le Bonheur du Jour, and his magnum opus Falbalas et Fanfreluches. Each entry was less a depiction of clothing than a coded whisper of who one might become if they wore it.

Barbier didn’t just draw Fashion. He aestheticized freedom.

A Shift in the Cultural Landscape

The 1920s were a carousel of upheaval disguised as glamour. Beneath the sparkle of flapper dresses and jazz clubs was a world unsure of its next step—rebuilding, reinventing, grasping for meaning in the ruins of old orders. In Paris, this uncertainty transmuted into brilliance. New movements collided: Poiret’s sensual minimalism, the Ballets Russes’ theatrical avant-garde, and the relentless cadence of mass production. And threading through it all, like a gilded ribbon, was George Barbier.

His art caught the moment not as it was, but as it ached to be—sleek, poised, and painted with longing. fashion was no longer a matter of cut and cloth; it was narrative. Each gown, a signal. Each page, a spell. In Barbier’s hands, the illustrated figure became a cipher for changing norms—of gender, class, and desire. The “modern woman” emerged not from manifestos but from silhouettes that dared to move.

And yet the Great War never fully receded. Even in opulence, Barbier’s work remembered. The symmetry, the ritualism, the historical echoes—they were all whispers of the fragility beneath the gloss. He was staging a revival, but he never forgot the funeral.

Key Publications

Each publication was a stage. Barbier, the conductor. His medium: illusion, precision, and that aching glamour only a war-scarred generation could dare to wear.

| Title | Description/Significance |

|---|---|

| Gazette du Bon Ton (1912-1925) | More than a fashion journal, it elevated illustration to high art. Here, Barbier wrote and drew with equal flair, defining the decade’s aesthetic from the inside. |

| Journal des Dames et des Modes (1912-1914) | A love letter to prewar Paris, it captured the city’s last gasp of prelapsarian luxury. Barbier’s pochoirs made its pages sing—until war silenced them. |

| Falbalas et Fanfreluches (1922-1926) | His five-volume opus. A baroque symphony of costume, story, and print that distilled the 1920s into a tactile dream. |

| Le Bonheur du Jour (1920-1924) | A shimmering study in manners and memory, this folio connected postwar chic with Empire-era grace, showing fashion’s ability to echo across centuries. |

Curtains Rise: Barbier on Stage and Screen

George Barbier, Le Jour et la Nuit (1922)

Captivated by Dance: Exquisite Éditions de Luxe

Barbier was never content to be confined by the flatness of the page. His visions begged for breath, for sequins that moved, for limbs that leapt across orchestral swells. And Barbier didn’t just adapt—the ballet gave him velocity and he orchestrated fresh visions. Dressing ephemeral moments in immortal line.

The Ballets Russes were no ordinary troupe; they were a cultural detonation. Under Sergei Diaghilev, the company redefined performance as gesamtkunstwerk—a total artwork. Barbier, mesmerized by this fusion of sound, story, and spectacle, entered their orbit with awe and ambition. Vaslav Nijinsky—scandal, swan, and saint—became a particular obsession. From this infatuation bloomed two rare gems: Dessins sur les danses de Vaslav Nijinsky (1913) and Album Dédié à Tamar Karsavina (1914), both lavish éditions de luxe, where pochoir met plié in a quiet riot of pigment and pose.

These books weren’t just fanfare. They were choreography frozen mid-flight, color applied with the tenderness of a pas de deux. Barbier translated movement into poise, and breath into curve. The ephemeral became tactile.

Though full records are elusive, Barbier’s hand is traceable across a constellation of legendary ballets: Schéhérazade, Carnaval, L’Après-midi d’un Faune, Petrouchka, perhaps even Le Spectre de la rose. He costumed Anna Pavlova, the era’s floating myth. In each case, he met the body not as constraint but as canvas.

Folies Bergère and the Silver Screen

By the mid-1920s, Barbier had scaled the height of Parisian spectacle—the Folies Bergère. With Erté, he conjured a procession of visual ecstasy: costumes that shimmered like broken stars and moved like whispers. The stage wasn’t just illuminated—it pulsed with narrative.

Cinema came calling next. In 1924, Barbier designed for Monsieur Beaucaire, dressing Rudolph Valentino not just in elegance, but in archetype. The New York Times applauded the artistry. Barbier had turned a silent film into visual opera.

He didn’t stop there. He costumed Casanova for Maurice Rostand in 1919 and brought Lysistrata to vivid life for Maurice Donnay. Across these ventures, his gift remained the same: to infuse historical fantasy with sensual clarity.

Each set, each silhouette, was a kind of conjuration—proof that illustration was not only art, but theatre, myth, and memory stitched into motion.

Key Collaborations

| Production / Role | Collaborator / Year |

|---|---|

| Various Ballets - Costume & Set Designer | Ballets Russes / Diaghilev (1910s) |

| Dessins sur les danses de Vaslav Nijinsky - Illustrator | Vaslav Nijinsky (1913) |

| Album Dédié a Tamar Karsavina - Illustrator | Tamar Karsavina (1914) |

| Folies Bergère Productions - Costume & Set Designer | Erté (Mid-1920s) |

| Monsieur Beaucaire - Costume Designer | Rudolph Valentino (1924) |

| Casanova - Costume & Set Designer | Maurice Rostand (1919) |

| Lysistrata - Costume Designer | Maurice Donnay (unknown) |

Illuminating the Written Word: Barbier as Book Illustrator

![]()

George Barbier, Seated Woman and Cherub (1929)

An Interpreter of Literature

Not all performance unfolds on stage. In the hush of finely printed pages, George Barbier found another canvas—more intimate, more deliberate. Here, the choreography was between text and image. His illustrations were not passive embellishments but active translations, converting literary rhythm into visual form.

He approached every commission as a collaboration between mediums. Whether conjuring the flirtations of Paul Verlaine’s Fêtes Galantes or the dusty allure of Théophile Gautier’s Le Roman de la Momie, Barbier’s pochoirs performed like quiet operas. Each image was a sensuous pause between paragraphs—rendered with precision, flushed with restrained desire.

Barbier’s literary works weren’t secondary to his fashion prints or ballet sets. They revealed a deeper, more introspective current: one where narrative, mood, and line coalesced into pure atmosphere.

Prestigious Titles and Poetic Depth

Barbier’s illustrated bibliography reads like a cabinet of decadent curiosities. He visualized the moody sensuality of Charles Baudelaire and brought scandalous elegance to Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’ Les Liaisons Dangereuses. That posthumous 1934 edition is still considered a masterpiece of twentieth-century book art—each pochoir pulsing with scheming glances and satin-draped malice.

He turned René Boylesve’s La Carrosse aux deux lézards verts into a fairy-tale of line and color, and infused Maurice de Guérin’s Poèmes en Prose with a gentle, melancholic lyricism. Pierre Louÿs’ Les Chansons de Bilitis, notorious for its erotic charge, found in Barbier’s hands a visual echo—equal parts reverent and provocative.

Each volume became a world unto itself: page as proscenium, typeface as libretto, image as aria.

The Art Deco Book Culture

In Barbier’s literary commissions, the Art Deco ideal crystallized. Line and geometry intertwined with narrative tone. Golds and carmines weren’t just ornamental—they were emotional. He didn’t illustrate scenes; he evoked subtext. Motifs snaked through margins, framing text like drapery or mosaic.

This was a golden era when artists and writers conspired—not just to adorn but to transform books into tactile spells. Barbier was among its most seductive magicians. He wrapped story in surface, turned sentiment into ornament, and gave literature a second skin.

In his pages, reading became more than comprehension. It became seduction.

Falbalas et Fanfreluches: The Crown Jewel of Personal Vision

George Barbier, Fumée (1921)

A Masterpiece in Five Parts

Between 1921 and 1925—plus a final installment in 1926—George Barbier composed Falbalas et Fanfreluches, a five-volume series that was part almanac, part love letter to the sensuous life. Here, for once, he was unbound. No house style to mimic. No commission to fulfill. Only his own voice, rendered in pochoir and prose, echoing across twelve plates per volume, each image accompanied by text from luminaries like Colette and Cécile Sorel.

The series was neither magazine nor book—it was ritual. A seasonal offering of imagined narratives and wearable fantasies. The romantic, the risqué, the mythic—all played out in Barbier’s meticulous theater of fabric, posture, and painted light.

Uncompromising Quality

Every volume of Falbalas et Fanfreluches was a masterclass in pochoir technique. Some plates required over thirty stencils, each hue laid by hand with patient precision. Color wasn’t applied—it was orchestrated. Pigments bloomed across the paper like silk catching candlelight. You could almost hear the rustle of the gowns, smell the perfume, feel the page resist under your fingertips.

These books were not mass-produced objects. They were handcrafted reliquaries of longing, each page a stage set, each print a gesture of devotion. They exemplified a kind of luxury rooted not in wealth, but in attention—the luxury of being deliberately made.

Evoking the Années Folles

This wasn’t escapism. It was embodiment. Barbier poured the rhythm of the 1920s into every vignette: flappers in moonlit gardens, languid lovers in gilded salons, decadent muses cast as allegories of sin. The 1925 volume rendered the seven deadly sins not as moral warnings, but as Art Deco divinities—gluttony in velvet, pride ablaze in gold.

Each issue of Falbalas captured the ephemeral mood of the années folles: elegance in excess, identity as ornament, history re-enchanted through surface and style. Barbier wasn’t illustrating a moment—he was crystallizing it.

The series was his most distilled creation: the dream of a world where beauty wasn’t luxury—it was law.

Le Bonheur du Jour: A Portrait of Fashionable Manners

George Barbier, L'étourdissant Petit Poisson (1914)

Manners Make the Woman (and Man)

In 1920, George Barbier unveiled Le Bonheur du Jour, ou les Grâces à la Mode, a folio as refined as a well-placed compliment and twice as disarming. Within its grand landscape format, he didn’t just illustrate clothing—he charted the choreography of charm. Sixteen pochoir plates, hand-colored by Henri Reidel under Barbier’s exacting direction, portrayed men and women not as models, but as social agents navigating the rituals of dress, flirtation, and self-display.

But beneath the velvet satire lay sincerity. Barbier wasn’t mocking manners—he was memorializing them, capturing fleeting codes of elegance before modernity swept them away.

A Hundred Years of Parallels

In his introduction to the folio, Barbier performed a kind of historical mirroring. He reached back to the post-Napoleonic world, drawing parallels between that age of aesthetic renewal and his own post-Great War moment. After every rupture, he suggested, society returns to ornament, not in denial but in declaration—frivolity as defiance, style as recovery.

He referenced Horace Vernet’s Incroyables et Merveilleuses—those absurdly attired dandies and muses who swaggered through Restoration salons with revolutionary bravado stitched into their lapels. Barbier’s 1920s figures weren’t imitations; they were descendants. Flappers as merveilleuses. Jazz Age as sequel.

It wasn’t nostalgia. It was historical rhythm.

Reflections of Shifting Societies

The images in Le Bonheur du Jour are not static portraits. They pulse with context—gender fluidity, shifting courtship rituals, the emergence of fashion as public theatre. Each pochoir is an observation: how a gesture can signify a worldview, how a gown can claim autonomy.

Barbier understood that style is never superficial. It is social language. Through delicate transitions of color, poised silhouettes, and meticulously staged backdrops, he captured a culture in flux. Not yet modern, not quite old, but suspended—gracefully—in between.

In Le Bonheur du Jour, manners weren’t rules. They were reflections. A way to say, without words, who we imagine ourselves becoming.

In Living Color: Decoding Barbier’s Pochoir Magic

George Barbier, Les Trois Beautes de Mnasidika (1922)

The Pochoir Technique

At the core of Barbier’s brilliance lies a process so tactile, so exacting, it borders on the monastic. Pochoir—French for “stencil”—was not just a method. In Barbier’s hands, it became a form of devotion. Unlike mechanical printing, which diluted color into mass production, pochoir preserved purity. Every layer of pigment—often gouache—was hand-applied through carefully cut stencils, sometimes thirty or more per image.

The result? Prints that breathe. Color that hums. Edges not flattened by ink but slightly raised, catching the light like embroidery woven from shadow. These were not illustrations. They were relics. Labors of pigment and patience. And Barbier orchestrated them like a conductor—tone by tone, layer by layer.

A Dance Between Geometry and Flora

In Barbier’s visual world, nothing stood alone. Hard angles met soft petals. Straight lines flirted with curves. His compositions moved like pas de deux—zigzags against tulip folds, stylized sunbursts set beside rococo curls. Art Deco was, in his hands, both declaration and seduction: geometry dressed in perfume.

Barbier embraced contrast with surgical elegance. Pale backgrounds set jewel tones ablaze. Gowns bloomed from dark silhouettes. And through it all, a kind of sacred symmetry: modernity rooted in classical proportion, ornament unashamed of its lushness.

Every line led somewhere. Every bloom had lineage.

Handcrafted in an Age of Machines

By the 1920s, industrial reproduction was ascendant. Magazines rolled off presses, and fashion moved at the speed of the assembly line. But Barbier refused haste. His pochoirs stood as quiet defiance—artworks made slowly, deliberately, in a world racing forward.

That choice wasn’t nostalgic. It was ideological. In Barbier’s Paris, handmade meant sovereign. Craft was not regression—it was resistance. Each stencil laid by hand was a gesture against forgettability, against the flattening of beauty.

The pochoir process, so laborious it verged on the sacred, anchored Barbier’s legacy. It proved that in the heart of a mechanized century, it was still possible to make something unforgettable—not because it scaled, but because it shimmered.

Worldly Whispers: Barbier’s Global Inspirations

George Barbier, Chez la Marchande de Pavots (1920)

Orientalism and the Allure of the East

In the 1920s, Europe turned its gaze outward—hungrily, exotically. Trade routes reopened, travel brochures multiplied, and salons filled with talk of silks, spices, and distant lands. In Barbier’s work, this fascination took visual root. He leaned into Orientalist aesthetics not with anthropological rigor, but theatrical abandon. His images of harem interiors, sultanic romances, and perfumed gardens are fantasy worlds filtered through the lens of French desire—seductive, stylized, often problematic in their cultural flattening.

And yet, within these scenes—domes glinting under stars, figures adorned in Persian-inflected finery—there is an undeniable reverence for surface. For color as story. For the richness of imagined elsewhere.

He wasn’t documenting the East. He was staging it. Framed not as geography, but as visual possibility.

Classical Grandeur and Japanese Precision

Counterbalancing this exotic intoxication was Barbier’s enduring dialogue with the ancient world. From Greece, he borrowed the stillness of marble. From Etruria, the clarity of contour. These weren’t references for show—they were structural. His figures often carried themselves like statues: poised, proportioned, eternal.

But it was Japan that refined his restraint. The Ukiyo-e prints of Hiroshige and Utamaro gave Barbier permission to flatten perspective, to let fabric flow like ink. From Persian miniatures came the logic of pattern: ornament not as background, but as environment. From Egypt, a language of symmetry. From Chinese and Indian art, rhythm and richness.

He was a cartographer of influence, plotting elegance across continents.

Eclecticism as a Signature

Barbier didn’t blend these references. He curated them—like a collector of rare perfumes, layering scents without muddling their clarity. In this lies the essence of Art Deco: not imitation, but synthesis. His was a world where a 1920s Parisienne might lounge like a Byzantine empress, framed by Japanese lattices and Greco-Roman drapery—unapologetically hybrid, thoroughly modern.

This wasn’t cultural sampling. It was visual diplomacy, orchestrated through silk, pigment, and poise.

In Barbier’s hands, influence was not theft. It was transformation. A dialogue across centuries and borders that left every line humming with cosmopolitan precision.

| Influence | Examples / Artists |

|---|---|

| English Illustration: Stylized lines, decorative patterns, emphasis on form. | Aubrey Beardsley, William Blake |

| Classical Antiquity: Idealized human form, clarity of line, classical motifs. | Greek and Etruscan Vases, Egyptian Art |

| Orientalism: Faraway settings, decorative motifs, use of rich colors and patterns. | Japanese Prints, Persian Miniatures |

| 18th Century French Art: Elegant figures, refined compositions, historical costume details. | Antoine Watteau, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres |

Jazz Age Reflections: Barbier, Society, and Shifting Norms

George Barbier, La Danse des Fleurs (1929)

Pages from a Liberated Decade

The 1920s glittered with the sheen of liberation—of women shorn of corsets and conventions, of men emboldened to step outside tradition’s shadow. Barbier’s illustrations traced this liberation not in manifestos but in the soft arc of a neckline, the casual tilt of a cigarette, the way two women might lean into each other beneath a moonlit balcony.

His work was not overtly political, yet it rippled with change. The “modern woman” emerged not just in the clothes he rendered—sleek gowns, dropped waists, bare arms—but in the way she occupied space: confidently, unapologetically, often center stage. She didn’t wait to be looked at. She looked back.

And beneath the shimmer, Barbier captured something rarer: intimacy without spectacle. Queer subtexts flickered in scenes of whispered affection and shared glances, coded and layered like the flowers of floriography. In an era where silence was often the only safety, Barbier’s illustrations whispered boldly.

Travel, Shopping, and Society Soirées

Barbier’s world was one of exquisite surfaces—of transatlantic voyages in mirrored cabins, soirées thick with perfume and piano, department stores transformed into temples of desire. His illustrations didn’t just dress the elite; they staged their rituals. Women stepped off trains in embroidered coats. Men lingered near perfume counters with secrets tucked in their breast pockets.

He rendered leisure with the gravity of ceremony. Each figure was composed, each gesture deliberate, as though beauty itself required discipline. Yet through all the finery, you could sense the undercurrent: that these rituals of consumption and display were also quests for identity. That Fashion was the script, and life the unscripted performance.

A Vibrant Record of Cultural Shifts

Taken together, Barbier’s work becomes a kind of social archive—one etched not in ink alone, but in posture, palette, and negative space. He documented not the great events of the 1920s, but their atmospheric residue: the tilt toward independence, the flirtation with fluidity, the triumph of style as a form of authorship.

Each pochoir plate is a freeze-frame of a world learning to move differently. And in those frames, Barbier gave us more than glamour. He gave us transformation in the language of silhouette.

A Legacy Beyond the 1920s

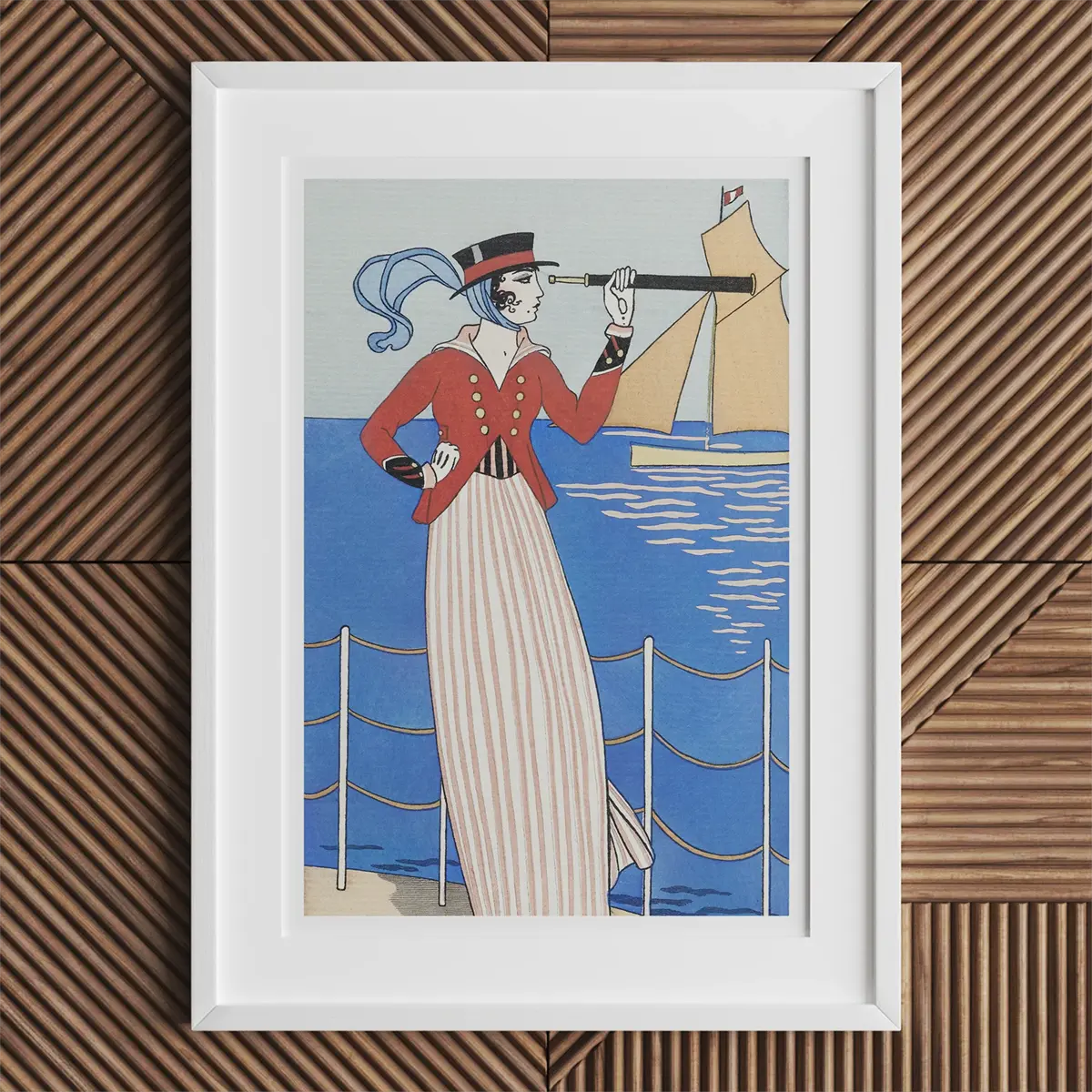

George Barbier, Costume de Yacht from Journal des Dames et des Modes (1914)

Sudden Silence, Gradual Reverence

George Barbier died in 1932, just shy of his fiftieth birthday. The page fell quiet. In a world newly obsessed with speed, efficiency, and modernist starkness, his pochoir prints began to fade from view like the scent of last night’s perfume. His name slipped into curated footnotes, his lush lines momentarily eclipsed by the leaner dogmas of design.

But art history is cyclical. What once felt excessive begins to shimmer again when minimalism grows cold. Barbier’s moment—sleeping like a pressed flower between chapters—began to reawaken.

Exhibitions surfaced. Scholars returned to his work not as nostalgia but as revelation. They saw not decoration, but precision; not escapism, but coded survival. In Barbier’s silences, they heard intention.

Imprints on Future Generations

Barbier’s influence was never loud. It was elegant, persistent, and undeniable. fashion illustrators through the mid-twentieth century traced his contours—his confidence in posture, his daring use of negative space. Haute couture houses, even now, nod toward his theatricality when crafting shows that privilege spectacle, story, and seduction in equal measure.

His compositions forecasted the rules of layout still used in editorial design: how to frame a figure, how to draw the eye through gesture, how to balance ornament with emptiness. His pages were stages, and every element had blocking.

Even in packaging design—perfume bottles, stationery, silk scarves—his echo lingers. Any brand that leans into drama and elegance owes something, knowingly or not, to Barbier’s orchestration of allure.

Rediscovering the Chevalier du Bracelet

In the 21st century, Barbier has returned—not as a footnote, but as a touchstone. Exhibitions, books, and academic revivals have restored him to the pantheon of visual innovators. We remember him now not only as a stylist of the Jazz Age, but as a seer who knew that beauty could carry cultural weight. That fashion was philosophy in disguise.

Barbier’s resurrection parallels our periodic return to the années folles—whenever the world breaks, we seek out the artists who stitched light back into the dark.

Eternal Flames of Pochoir and Elegance

George Barbier was never merely a stylist. He was a conjurer—an alchemist of line and light—who proved that elegance could be radical, and that beauty, properly wielded, could withstand the blunt force of time. His art wasn’t commentary. It was enchantment made deliberate. And through the painstaking devotion of pochoir, he gave that enchantment form—layered, luminous, defiantly tactile.

He drew not just fashion, but possibility. Figures in his prints seem to inhabit some mythic Paris—one where Greco-Roman clarity meets Persian ornament, where a Japanese screen might frame a Jazz Age embrace, and where identity was a costume one could choose with reverence or abandon. Every plate he touched became a world. Every figure, an archetype. Every composition, a tableau both ephemeral and eternal.

And it lingers still. His hand-colored prints whisper across time. You see them and you feel the hum of a Parisian night: sequins catching stage lights, the perfumed hush of gallery halls, the breathless space between two dancers on a marble floor. His women aren’t just beautiful—they’re incandescent with intent. His men, languid with stylized grace. In each gesture, a philosophy of poise.

Barbier didn’t illustrate a generation. He preserved its dream.

To open his portfolio today is to trespass through time: into a place where restraint and flamboyance embrace, where surface reveals soul, and where color becomes a kind of resistance to forgetting. Amid the churn of decades and the erasure of nuance, Barbier’s work insists on detail, on craftsmanship, on the ceremonial act of looking.

The Chevalier du Bracelet remains a fixed point in the constellation of cultural renaissance—a compass for those who believe beauty can still mean something. That it can defend, seduce, and illuminate all at once.

We return to him not to escape the present, but to remember that after every ruin, there is always someone with a brush—quietly painting the next beginning in strokes of gold and midnight blue.