The term Ukiyo-e (浮世絵) floats into the mouth like mist and iron, a breath stitched from three kanji: 浮 (uki), fleeting or buoyant; 世 (yo), the orbit of eras and fortunes; 絵 (e), a bloodline of pictures. Once, in the cracked mirror of Buddhist sorrow, ukiyo was the sorrowful world (憂き世), a wheel of anguish spun by samsara’s indifferent hand. To live was to suffer, to float helplessly toward oblivion.

But as the sluice gates of the Edo period swung open, ukiyo molted its sadness. In the sweating, bawdy bloom of Edo, Osaka, and Kyoto, the floating world crackled alive: a neon tide where sorrow mutated into indulgence. The floating world became the tremor of lanterns outside a kabuki theater, the drunk whisper inside a teahouse, the shiver of skin behind the lattice of a brothel. The manic dream of Yoshiwara was no longer to transcend suffering — it was to adore it while it burned.

Into this phosphorescent storm sailed Ukiyo-e, the picture of the floating world: at once elegy and exultation, a reckless love letter to the here and now. Ukiyo-e did not merely illustrate; it stitched the ephemeral into permanence, each line a whispered rebellion against impermanence itself.

Capturing a Fleeting World: Art for a New Class

At its marrow, Ukiyo-e carried two bloodstreams: the hushed dignity of paintings, and the populist roar of woodblock prints. It became the mirror for the chonin, the merchant class swelling within the capillaries of the Edo Period — rich in coin, poor in official esteem, hungry for beauty made tangible.

Ukiyo-e answered with an ink-bloom riot. Ukiyo-e prints flooded the city stalls, each cheap enough to slide into the hand of a fishmonger or a teahouse girl. Woodblock prints became a democracy of desire: a courtesan’s glance, a traveler’s footfall, a mountain dissolving into cloud. The shifting meaning of ukiyo — from mournful drift to ecstatic embrace — reflected in the watery eyes of a rising merchant class, now writing its dreams not in prayers but in paper and pigment.

Ukiyo-e emerged as a tactile theology, a sacred vulgarity. It baptized the everyday — the sweat of an actor mid-pose, the fraying hem of a geisha’s obi — and gave it to the people for the price of a bowl of noodles. Woodblock prints tethered life’s evanescent breath to a permanent artifact: a print to hold, to love, to outlast the night.

Key Takeaways

-

Ukiyo-e woodblock printing emerged in Japan during the Edo period (1603–1868), becoming a widespread form of artistic expression that captured the fleeting world of urban life.

-

Traditional Ukiyo-e techniques involved intricate carving into wooden blocks, meticulous ink application, and the pressing of paper onto the carved surface—processes that could later be enhanced with chromolithographic innovations.

-

Common themes in Ukiyo-e prints included the idealized portraits of beautiful women (Bijin-ga), dramatic depictions of Kabuki theater performances, and vivid portrayals of Yokai creatures from Japanese folklore.

-

The selection of washi paper, crafted from mulberry bark, hemp, and other natural fibers, was crucial to achieving the strength, absorbency, and delicacy needed to preserve the vibrant pigments during the block-printing process.

Beginnings of Ukiyo-e: How Japanese Woodblock Prints Gave Birth to Early Ukiyo-e

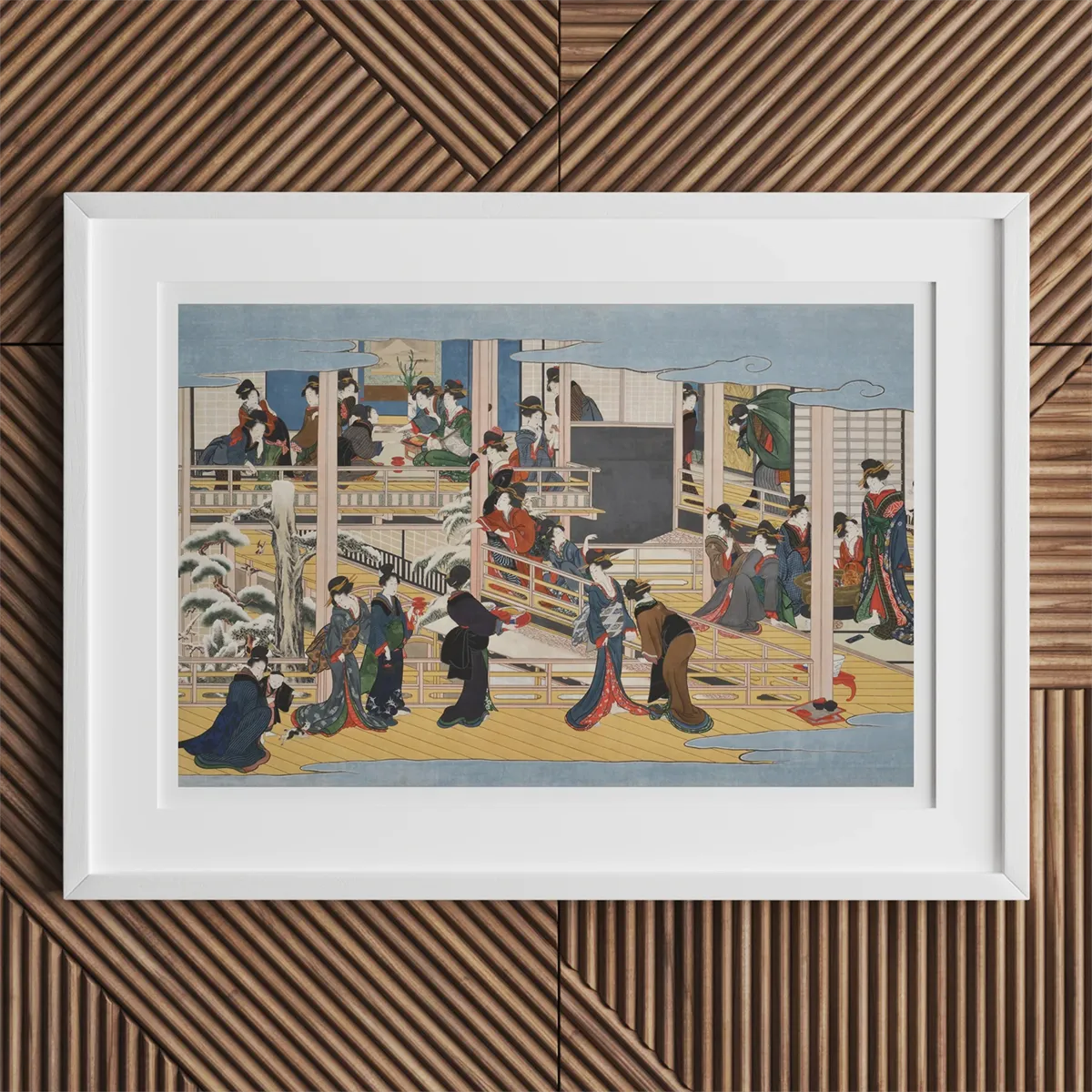

Chōbunsai Eishi, Geisha Preparing for an Entertainment (1794 CE)

The Edo Period Foundations

The Edo period, a seismic hush after centuries of swords and smoke, unfolded like lacquered screens across the land from 1603 to 1868. Under the iron fan of the Tokugawa shogunate, peace became the new climate, and Edo—that sprawling river city—grew into a beating, mercantile heart. Markets heaved with fishmongers and silk vendors. Laughter clattered through the alleys. Stability, that rare and delicate bird, finally perched on Japan’s shoulder.

But stability breeds more than crops. It cultivates appetite—for beauty, for novelty, for the lush now. It was within this thickening air of ambition and indulgence that the seeds of Ukiyo-e quickened.

Merchant Class Influence

Below the high seats of samurai and priests, the chonin—merchants and artisans—tilled new fields: fields of fashion, poetry, pleasure. Their position in the rigid social edifice was low, their purses heavy, their hunger radiant. Deprived of political clout by decree, they seized what was left: the dominion of taste.

And so, they remade the floating world in their own image: brocaded, raucous, temporal. Ukiyo-e—both mirror and map—charted this territory of longing, indulgence, and aspiration. It was a revolution waged in pigments rather than proclamations.

Artistic Evolution

Ukiyo-e did not erupt fully formed from the loins of imagination. It coalesced, slowly, like mist lifting from a river. Its lineage can be traced to the courtly lyricism of yamato-e, the "Japanese style" of painting, and to the imported structural vigor of kara-e, steeped in Chinese aesthetics.

In its early breath, ukiyo-e whispered itself across hand-painted scrolls and lacquered screens, glimpses of a world half-real, half-dreamed: the tilt of a parasol, the arch of a bridge, the sharp lilt of a geisha’s laugh. These artifacts, singular and precious, still bore the heavy perfume of aristocratic exclusivity.

But a storm was coming.

The Rise of Woodblock Printing

That storm had a name: woodblock printing.

First birthed to spread the solemn syllables of Buddhist sutras, the technique would slip from prayer to pleasure. The carved block, once a vessel for divine scripts, now turned its grain toward flesh and laughter, theater and tea.

The architect of this secular rebirth was Hishikawa Moronobu (1618–1694)—the progenitor of the ukiyo-e print. With a calligrapher’s hand and a rogue’s eye, he siphoned life into black-and-white forms: courtesans in repose, sumo wrestlers mid-lunge, actors caught between breath and performance. Monochrome, yes—but already trembling with the riot of life.

Color Innovations

Demand frothed like sake. A mere wash of hand-colored accents no longer sufficed. By 1765, a new magic crystallized through the hands of Suzuki Harunobu: nishiki-e, or "brocade prints."

Here, multiple woodblocks, each breathing a different color, aligned through clever kento notches. The world now exploded onto paper in cascading vermilions, viridian ponds, indigo robes.

Ukiyo-e could finally sing in a full register, not merely whisper through grayscale sighs.

Cultural Significance

In this flowering, the true democratic soul of Ukiyo-e was revealed. Art, once the solemn purview of the elite, now unfurled in the muddy lanes and vibrant marketplaces. The shift from singular, hand-painted scrolls to mass-printed woodblock prints marked not just a technical innovation—it declared a cultural insurrection.

For the chonin, Ukiyo-e was more than decoration. It was an affirmation, a seduction, a clenched fist against invisibility. The new full-color vistas captured not just faces and landscapes, but the dreams of a people unmoored from the strict hierarchies of birth, navigating the floating world with pockets full of painted paper stars.

From Hand to Block: The Art and Craft of Ukiyo-e Printmaking

Katsushika Hokusai, Kozuke Sano Fune-bashi No Kozu (1834 CE)

Collaborative Creation

The creation of a Ukiyo-e print was not the solitary scribble of a lone dreamer but a cathedral of touch—an orchestra conducted across skin and wood, paper and pigment. Every print braided the labors of four artisans: the publisher, the artist, the carver, and the printer.

The publisher, keeper of coffers and public hunger, funded the vision and marshaled the invisible threads between artisans. The artist, wild and sharp, bled images onto delicate paper with ink—no second drafts, no forgiveness. The carver, a sculptor of ghosts, took blade to cherry wood, translating fragile lines into a block dense with potential. Cherry wood, dense and obedient, whispered back in every stroke; its tight grain was an archive of patience, perfect for holding the breathless precision of design.

And finally, the printer, part alchemist, part sorcerer, breathed color into the whole: pressing ink against paper with a tool called the baren—a pad spun from twisted cord and veiled in bamboo skin. Every press a prayer. Every print a miniature rebirth.

Materials and Techniques

In this high-stakes ballet, material was no afterthought—it was gospel. The woodblocks cradled either fine-grained cherry or resilient boxwood, chosen for their dual nature: firm enough to withstand countless impressions, soft enough to carve without splintering the dream.

The inks, alive with water’s fickle spirit, blended earth pigments with sticky tendrils of nori, the Japanese rice paste, binding color to breath. The first among equals, the key block, carried the skeletal grace of the design—etched in crisp sumi ink, stark and merciless.

And then came the paper: washi, coaxed from mulberry bark and the supple strength of hemp, a surface both yielding and hungry, able to sip pigment and hold it like a long-lost love. Without washi, no beauty could endure.

Multi-Block Printing and Effects

To birth a print in full-throated color—the miracle of nishiki-e—required a separate block for every whisper of hue. Each carved slab aligned to the others with ruthless intimacy, guided by twin registration marks, the sacred kento cuts.

Color built upon color in slow, patient strata: indigo clouds hovering over vermilion roofs, ochre lantern light swimming across jade gardens. Techniques like bokashi smeared the ink in deliberate gradients, breathing dusk and dawn into a single image. Each pass risked misalignment, a fracture in the dream. Precision was not luxury—it was law.

Evolution of Printing

The earliest Ukiyo-e prints, baptized in monochrome sumizuri-e, were stern, almost ecclesiastical: black sumi ink upon the naked expanse of paper, solemn as sutras. Early color came clumsily, hand-painted onto prints with bright pigments—a flash here, a smear there—called tan-e, their hues sometimes corrupted by sulfur or mercury’s unruly alchemy.

But then came the thunderclap: nishiki-e’s full symphony of color, forged from multi-block mastery. Suddenly, prints no longer hinted at life—they roared.

Collective Ingenuity

The making of Ukiyo-e was an act of impossible trust: hundreds of moving parts, dozens of invisible hands, and a single goal—to trap the ungraspable moments of a floating world. It was a collaboration so intimate that no single name could ever truly own it.

The fine grain of cherry wood, the thirsty kiss of washi paper, the delirious gleam of water-based pigments—all conspired together. From the severe line of monochrome sumizuri-e to the lush explosions of nishiki-e, the evolution of Ukiyo-e was not an accident. It was a feat of collective brilliance, carving fleeting joy into the bones of permanence.

A Universe of Images: Unveiling the Diverse Genres and Themes of Ukiyo-e

Utagawa Toyokuni, One Hundred Looks of Various Women (1816 CE)

Bijin-ga: Pictures of Beautiful Women

In the riverlight of Ukiyo-e, few subjects shimmered more fervently than the bijin-ga—pictures of beautiful women. These were not mere portraits; they were incantations, stitched from silk, scent, and social ambition. The courtesans and geisha of the pleasure districts, immortals of the moment, stared out from the prints with an elegance designed to blur the line between myth and marketplace.

Their hair piled like constellations. Their robes bloomed with patterns that whispered secret codes of class, desire, and season. Artists like Kitagawa Utamaro wielded the okubi-e—the "large head picture"—to tilt the entire world around a single gaze, as if the universe had briefly condensed into the lacquered curve of an eyelid.

The bijin-ga was no passive genre: it invented and broadcast ideals of beauty that would ripple through fashion, poetry, and the scented air of Edo's pleasure quarters for generations.

Yakusha-e: Pictures of Actors

Where bijin-ga exalted beauty’s unbroken mask, the yakusha-e ripped it open mid-performance. These pictures of actors seized the kinetic snarl of the kabuki stage—actors locked in mie poses, faces split between ecstasy and terror, robes flaring like banners in a storm.

Each yakusha-e served double duty: advertisement and artifact, a billboard and a relic. They immortalized not the actor alone, but the fevered, hyperreal character that audience and performer together conjured from smoke and drumbeat. The enigmatic Sharaku, active a heartbeat between 1794–1795, slashed through theatrical glamour to reveal raw nerve endings, often verging on caricature.

In a world obsessed with appearances, yakusha-e captured the molten machinery underneath the mask.

Musha-e: Warrior Prints

The pulse quickened in the domain of musha-e—pictures of warriors. Here, swords kissed the air, banners bled into clouds, and heroism howled across the paper. These prints mapped a Japan not of shogunate stability, but of mythic battles and avenged ancestors, a world where valor could still cleave mountains.

Artists like Utagawa Kuniyoshi drenched their musha-e in visual thunder: waves cracking open cliffs, ghosts shrieking through armor plates, tigers snarling at the hem of dreams. To own a musha-e was to clutch a sliver of a fiercer Japan, one that still believed redemption could be forged at swordpoint.

Fukei-ga: Landscape Prints

When weariness frayed the edges of the floating world, the gaze lifted to distant peaks and unspooled rivers. The fukei-ga—landscape prints—offered a balm against the clamor of cities, rendering the chaos of life into pathways of mist and stone.

Katsushika Hokusai etched eternity into wood with his Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, none more iconic than the clawing elegance of The Great Wave off Kanagawa. In contrast, Utagawa Hiroshige traced the gentle arteries of travel with his Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, where travelers became specks swallowed by seasons and road.

The fukei-ga was less map than memory: a landscape not just seen but felt across the bones.

Other Fascinating Genres

Beyond these keystone genres, Ukiyo-e branched into a tangle of fascinating tributaries:

-

Shunga (春画) unfurled erotic art, alternately playful and transgressive, stitching sex into the fabric of daily life.

-

Kacho-ga (花鳥画) crowned birds and flowers with almost religious reverence, capturing the dance of seasons in a single frozen breath.

-

Yokai-ga (妖怪画) dredged up supernatural phantoms: fox spirits, ogres, and wayward souls flaring through haunted paper.

The floating world mirrored itself through Sumo-e, portraying sumo wrestlers as mountain gods mid-clash; through Abuna-e, skating the edge of erotic suggestion; through Asobi-e, play-prints spun for children’s delight. Calendars disguised themselves as art in E-goyomi, while the vertical slivers of Hashira-e decorated the narrow columns of merchant houses.

Later, as the world shifted, Nagasaki-e and Yokohama-e recorded the uneasy infiltration of Western ships and fashions. Senso-e thundered with news of the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars. And in the Meiji Era, Kaika-e heralded Japan’s headlong plunge into Western modernity, its figures straddling old dreams and new steel.

Cultural Insight

The spectrum of Ukiyo-e genres offered a panoramic archive of Edo period society: a painted palimpsest where beauty, violence, longing, play, fear, and transformation all jostled for space.

Through bijin-ga, we glimpse aspirational elegance.

Through yakusha-e, the mask drops.

Through musha-e, the sword flashes.

Through fukei-ga, the path winds home.

Through shunga, the human heart reveals itself without apology.

The floating world was not monolithic. It was a hall of mirrors—frivolous, brutal, tender, terrifying—each genre a separate reflection, each print a desperate attempt to anchor what would otherwise drift beyond memory.

The Pantheon of Masters: Iconic Artists Who Shaped the Ukiyo-e Tradition

Katsushika Hokusai, The Great Wave Off Kanagawa (1826-33 CE)

Katsushika Hokusai

The story of Ukiyo-e burns brightest where Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) split the sky itself. A master whose spirit seemed forged from river currents and temple smoke, Hokusai bent the wooden block to map the unseen architecture of existence. His The Great Wave off Kanagawa, thunderous and curling, is not merely an image — it is the heartbeat of chaos rendered in a single, perfect shudder.

Through his sweeping Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, Hokusai turned a singular mountain into a prism of human longing. His colors breathed beyond pigment; his lines dreamed beyond borders. Hokusai’s genius wasn’t simply technical — it was tectonic. His fingerprints ripple through Western Impressionism, through modern design, through any moment that tries to catch beauty as it flees.

But he never chained himself to one artform. Monsters danced through his yokai-ga, his brush flicking open doors to supernatural landscapes with the same reverence he applied to Fuji’s immutable slopes. If Ukiyo-e captured the floating world, Hokusai captured its underlying tides.

Utagawa Hiroshige

If Hokusai thundered, Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) whispered.

Where Hokusai seized the eye, Hiroshige seduced it: winding paths of mist, sighs of rain between reed stalks. His The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō dissolved travel into poetry, a pilgrimage of the senses rather than the soles. Travelers blur into seasons. Bridges dream of vanishing into the river’s own forgetting.

In his One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, Hiroshige turned the metropolis into a breathing, moody lover — at once grand and crumbling, fleeting and eternal. His ability to layer atmosphere like fine lacquer changed the vocabulary of art itself, inspiring European artists who had never set foot in Edo, but who found themselves haunted by Hiroshige’s skies.

Perspective was his secret weapon: plunging the viewer downward into scenes, sideways into corridors of memory. He slipped into the soul of landscape and revealed it to itself.

Kitagawa Utamaro

The pulse of the human face — its silences, its tremors — belonged to Kitagawa Utamaro (c. 1753–1806).

Best known for his luminous bijin-ga, Utamaro raised the art of beautiful women from decoration to meditation. His close-up portraits, often fashioned in the okubi-e format, capture neither mannequins nor archetypes, but breathing women: weary smiles, mischievous glances, moments of unguarded daydreams.

His genius lay in bending the visual field itself: elongating necks, amplifying the languor of a gaze, letting the lines of a kimono pool like water. He stitched Fashion, psychology, and eroticism into a single seamless tapestry.

In Utamaro’s world, beauty isn’t posed. It simply happens — like a plum blossom shivering on the branch before it falls.

Tōshūsai Sharaku

A phantom who blazed and vanished, Tōshūsai Sharaku remains the great enigma of Ukiyo-e.

Active for less than a year (1794–1795), he produced yakusha-e portraits of kabuki actors so raw, so ruthlessly alive, that they seemed to bleed directly onto paper. Where other artists flattered, Sharaku confronted. His actors are grotesque, godlike, human in their flaws — grimacing, bulging, straining against the mask of performance.

Sharaku didn’t just depict roles; he excavated personas. His linework slashed through pretense like a katana. For this, he vanished — or was made to vanish — leaving behind a body of work that still feels like an unsolved crime scene: haunting, luminous, unresolved.

Other Influential Figures

Beyond the towering peaks of Hokusai, Hiroshige, Utamaro, and Sharaku stood a constellation of innovators:

-

Hishikawa Moronobu sketched the genesis of Ukiyo-e itself, formalizing the everyday into subjects worthy of artistic immortality.

-

Suzuki Harunobu revolutionized the field with his development of nishiki-e, the full-color woodblock print, igniting a chromatic renaissance.

-

Torii Kiyonaga captured grace not as a frozen gesture but as a moving force, his tall, slender beauties often inhabiting open, sun-drenched spaces.

-

Utagawa Kuniyoshi unleashed myth and muscle into his musha-e, where samurai and supernatural forces collide with cinematic fury.

-

Keisai Eisen, master of the urban portrait, mapped the shifting undercurrents of beauty and place, rendering the city itself a co-conspirator.

Each artist bent the floating world to a new lens: a mirror smashed and reassembled, reflecting a society’s secret heart.

Enduring Impact

Together, these masters forged Ukiyo-e into a living organism, not a genre: something that still flickers in neon lights, in whispered gestures, in waves of design and cultural memory.

Their techniques crossed oceans — sparking the fire of Japonisme, inspiring the broken perspectives of Impressionism, the flowing lines of Art Nouveau. Their dreams are stitched into the very grammar of modern aesthetics.

The floating world did not drown when its moment ended.

It drifted outward, dissolving borders, still shimmering, still beckoning.

Beyond Aesthetics: The Profound Cultural Significance of Ukiyo-e in Japan

Kikugawa Eizan, Summer at Ryogoku in Edo (1811 CE)

The veins of Ukiyo-e ran thick with theater blood. No art form better captured the electric thrum of the kabuki theaters, where masked actors and masked emotions tangled like silk threads in the dark. Yakusha-e prints served as both sacred relics and street advertisements—ephemeral flashes of drama pressed into permanence.

Each sheet of paper, inked with a moment of fierce pose or violent stillness, was a portal: for the commoner who could never afford the good seats, for the devotee who clutched portraits of their favorite actors like charms against mediocrity. Through Ukiyo-e, the spectacle of Kabuki did not end at the curtain’s fall — it spread through the city, embedding itself into the dreaming tissue of everyday life.

Ukiyo-e did not merely document Kabuki. It oxygenated it, expanding the theater's reach beyond stage boards into the palmed intimacy of the printed image.

Influence on Fashion and Textiles

The ink of Ukiyo-e bled into cloth, into commerce, into bodies moving through the dust and neon of Edo’s markets. The swirl of waves in a woodblock print became the stitched arc of a kimono hem. The crook of a geisha’s wrist, etched in thin black line, became the aspiration of thousands folding sleeves just so.

Printmakers were not just artists; they were fashion’s shadow architects. The motifs that danced across Ukiyo-e—plum blossoms, birds perched on curling branches, waves cresting with the violence of desire—leapt from paper to loom, from loom to skin.

fashion itself became an extension of the floating world’s impermanence: colors chosen for the brevity of seasons, patterns for the brief intoxication of trends. Ukiyo-e dictated not just what was seen but how one was seen.

Reflection of Popular Culture

Above all, Ukiyo-e was the floating world’s own mirror: cracked, stained, exuberant. It chronicled the sumo tournaments that thundered through Edo, the firework festivals that exploded over its rooftops, the mythic beasts that crawled between drunken songs.

It reflected the desires of the chonin class — their hungers, their sorrows, their celebratory defiance of rigidity. In a society still weighed by class and duty, Ukiyo-e carved out a new republic of images where commoners could see themselves rendered monumental and lush.

Beyond entertainment, Ukiyo-e functioned as living advertisements: for tea houses, for travel routes, for brothels and theater performances. The art was commerce. The commerce was art. No line separated the floating world from the real one; each print blurred the distinction further.

Symbolic Harmony

In the interplay between image and performance, between cloth and street, Ukiyo-e formed a symbolic ecosystem: every print a conversation with the city's living pulse.

The bond between Ukiyo-e and Kabuki was a circulatory system of visual and performative breath. The translation of printed waves into embroidered sleeves revealed the art form’s ability to not just mirror culture but inhabit it. And the widespread availability of Ukiyo-e—cheap, portable, intoxicating—meant that even the lowest-born citizen could clutch a piece of the dream, a shard of the floating world, and call it theirs.

In the ephemeral theater of Edo life, Ukiyo-e was the prop, the stage, and the applause—etched in wood, pressed into memory.

Across Oceans and Eras: Ukiyo-e’s Enduring Global Influence and Legacy

![]()

Katsushika Hokusai, Umezawa Manor in Sagami Province (1830-32 CE)

Japonisme in the West

By the nineteenth century, Ukiyo-e had slipped its borders like smoke through a cracked window. As Japan reopened to the West, these woodblock dreams—sheets of vibrant air and ink—washed ashore in Europe, strange and dazzling. Artists, critics, and collectors gorged themselves on a vision of the world unfiltered by Renaissance linearity or bourgeois gloom.

The fever had a name: Japonisme.

Painters like Vincent van Gogh, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec did not merely admire Ukiyo-e; they devoured its asymmetrical compositions, its plunges into bird’s-eye perspectives, its refusal to treat shadow as obligation. The bold, flattened color planes of Ukiyo-e rewired the Western brain, helping to dismantle centuries of pictorial expectation.

Monet's water lilies floated closer to Hokusai's waves than to any European stream. Van Gogh’s thick strokes and rising suns carried the ghost of Ukiyo-e's compressed eternities. Even in the smoke-drenched cabarets of Paris, Toulouse-Lautrec’s dancers flared across the stage like kabuki actors caught mid-gesture.

Ukiyo-e was not merely imported. It detonated inside Western art.

Contemporary Resonance

That detonation still echoes.

Today, Ukiyo-e breathes inside contemporary art, graphic design, manga, advertising, and visual culture across continents. It lurks in the clean hunger of branding, in the playful violence of anime, in the minimalism of poster art. The DNA of Ukiyo-e—its audacity with space, its braiding of the everyday and the mythic—continues to mutate and thrive.

Modern artists plunder its palette and its possibilities. Some mimic its lines in homage; others steal its spirit to forge new languages altogether. In either case, the floating world never sank—it simply changed oceans.

Ukiyo-e lives wherever the fleeting is celebrated and the still moment explodes outward into eternity.

Lasting Mark on Art History

The legacy of Ukiyo-e is not polite appreciation; it is permanent mutation.

It shifted the gravitational pull of art history, dragging Western modernism toward new orbits: Impressionism’s loose boundaries, Post-Impressionism’s violent colors, Art Nouveau’s whiplash curves. Ukiyo-e taught the West how to see again—not through the heavy glass of realism, but through the quicksilver of perception.

Even now, its ripples widen. Museum walls strain to contain its velocity. Design studios canonize its principles. The "floating world" never finished floating—it bled forward, backward, outward—remaking how beauty could move, how moments could matter.

In every image that captures the ephemeral with ruthless clarity, Ukiyo-e breathes.

Echoes of Modernity: Ukiyo-e in the Meiji Era and its Transition to Contemporary Forms

Kitagawa Utamaro, Fukagawa no Yuki (1788–91 CE)

Meiji Restoration Impact

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 cracked open Japan like a lightning bolt splitting an ancient pine. Swords became railroad tracks. Tea houses blurred into telegraph lines. In this jarring modernization, Ukiyo-e found itself gasping for air—an artform birthed in a floating world, now drowning in iron and steam.

Artists adapted because survival demanded it. They swallowed Western perspective: forced linear vanishing points into their prints, injected shadows sculpted like European oils. Synthetic dyes exploded the palette into chemical hues. Themes shifted from the languorous flow of courtesans and rivers to the shriek of steamships, factories, and Western suits rustling down Edo's repaved avenues.

But even as the old floating world fractured, it did not vanish. It metastasized, echoing itself through the new cityscape.

Newspaper Illustrations

One vital artery of Ukiyo-e's mutation pulsed through the rise of nishiki-e newspapers. Using the beloved woodblock printing techniques, artists documented earthquakes, assassinations, scandals—turning the floating world’s lyricism toward the brutal immediacy of journalism.

No longer confined to beauty and pleasure, Ukiyo-e bared its teeth to chronicle upheaval: a world where the ephemeral now included telegrams and torpedoes. In an ironic twist, an artform obsessed with fleeting pleasures became the watchdog of fleeting horrors.

Key Meiji Artists

Within this vortex, certain figures refused to sink. They bent Ukiyo-e’s spine without breaking it:

-

Toyohara Kunichika infused his actor portraits with vivid modern color, even as their kabuki subjects clung to tradition.

-

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, haunted and brilliant, flayed the human psyche across his prints, often fusing samurai ghosts with the visual DNA of Western storytelling.

-

Kobayashi Kiyochika birthed the haunting kosen-ga, or "light ray pictures," capturing city streets blurred by gaslight and fog, images trembling on the edge between past and future.

-

Utagawa Yoshitora recorded the foreign ships, new fashions, and diplomatic contortions of a Japan wrestling itself awake.

Each artist stood astride two worlds—one dissolving, one erupting.

Decline and Evolution

Despite these luminous flickers, the old heartbeat faltered. Photography stormed the visual imagination. Oil painting, heavy and self-important, swaggered into galleries. By the late Meiji era, traditional Ukiyo-e had dwindled, a paper ghost haunted by mechanical shutters and imported pigments.

But art, like water, finds new riverbeds.

In the early twentieth century, new movements rose:

-

Shin-hanga ("new prints") revitalized Ukiyo-e's visual language, blending nostalgic subjects with the lush textures of modern printmaking.

-

Sosaku-hanga ("creative prints") ripped apart the collaborative model, demanding the artist control every stage—from design to carving to printing—birthing fiercely personal, often abstract visions.

The floating world floated onward, shedding skin after skin.

Lasting Legacy

The Meiji era did not kill Ukiyo-e; it detonated it into new forms.

The rise of nishiki-e newspapers, the absorption of Western visual logic, the emergence of new printmaking philosophies—all pointed to Ukiyo-e's deeper truth: it was never static. It was change incarnate, survival inscribed in wood and ink.

Though the floating world as once known receded, its fragments embedded themselves in modern Japan’s pulse: in advertising, in manga, in graphic novels, in visual dreams that still bear the woodgrain scars of old cherry blocks.

Ukiyo-e did not sink. It adapted.

And in doing so, it taught future generations how to drift forward without drowning.

Preserving the Ephemeral: The Delicate Art of Conserving and Collecting Ukiyo-e

Katsushika Hokusai, Fuji Seen from Kanaya on the Tōkaidō Artwork (1830–32 CE)

Conservation Challenges

To preserve Ukiyo-e is to cradle a dragonfly on your palm: beauty poised forever on the edge of rupture. These prints, birthed from rice paste and mulberry bark, are profoundly mortal.

Their enemies are omnipresent: light that gnaws, humidity that sours, pollution that corrodes, careless fingers that bruise.

Conservation demands a kind of sacred meticulousness: the art of slowing decay without embalming life. It begins with gentle backing removals, lifting acidic death masks from a print’s fragile skin.

Surface washing follows—no ordinary soap, but water whispering away centuries of soot and breath. Tears must be stitched delicately, holes filled as if mending an ancestor’s heartbeat.

Deacidification stabilizes the fragile paper, neutralizing invisible timebombs embedded by exposure. And all of it means nothing without armor: acid-free mats, humidity-controlled sanctuaries, UV-shielded glass coffins designed to honor survival, not flaunt possession.

Even framed, Ukiyo-e prints must live in the dim: light, both natural and artificial, is a slow knife against their pigment’s pulse.

Modern Methods

Science, too, has folded itself into the guardian’s craft.

High-resolution digital scanning now captures the minute veins and frayed silk of original prints without a single human touch.

Laser cleaning burns away the grime of centuries with the precision of a surgeon, vaporizing impurities that would shred paper if scrubbed.

Thermal and light-controlled treatments coax stubborn stains from the fibers without chemical violence. And in rare cases, inkjet printing conjures perfect facsimiles—allowing the soul of a piece to be shared in light while its body rests, cloistered and safe.

Yet even these miracles bow to the ultimate truth: the original, once damaged, carries scars forever. The best restorers are not healers. They are archivists of fragility.

Collecting Ukiyo-e

To collect Ukiyo-e is to collect light caught between rainstorms.

One must hunt with reverence and skepticism alike. The artist’s fame matters—Hokusai, Hiroshige, Utamaro—but so does the condition: the vibrancy of pigments, the strength of fibers, the absence of wormholes or bleeding inks.

Age does not sanctify without preservation; a battered rarity may hold less value than a pristine print from the same era.

Subject matter carries its own hierarchy: a spirited kabuki actor, a whispering courtesan, a wave that still threatens the shore. Certain images, by their cultural gravity alone, magnetize collectors across generations.

And then there is authentication—the ruthless x-ray gaze required to verify signatures, publisher seals, edition marks, and subtle histories encrypted in washi's weave.

Proper Care

To own Ukiyo-e is not to conquer it—it is to steward its impermanence.

Prints must live wrapped in acid-free folders, breathing in darkened vaults where temperature and humidity remain docile. Frames must shield without suffocating, letting washi flex and shrink with seasonal breath.

Handling demands gloves or bare, oil-free fingers brushed lightly along margins. Never touch the inked skin itself; even the warmth of admiration is corrosive.

And always, always: remember that Ukiyo-e was born for joy, for circulation, for impermanence. To preserve it is to love it without seeking to freeze it. Every act of conservation must honor not just survival, but transience.

A Lasting Impression: The Enduring Allure and Timeless Beauty of Ukiyo-e

![]()

Katsushika Hokusai, Gaifū Kaisei (1830–32 CE)

Ukiyo-e, the floating hymn of the Edo period, did not simply depict life—it transfigured it. In these prints, the ephemeral found scaffolding; the flickering gestures of daily joy, ambition, beauty, and fear crystallized into images sturdy enough to withstand centuries of forgetting.

Their genres scattered like blossoms across the canvas of human experience:

— The lacquered grace of beautiful women, captured in the soft-breath portraits of bijin-ga.

— The kabuki stage's seismic gestures, frozen mid-exclamation in yakusha-e.

— The blood-slick honor of warriors etched into the desperate thunder of musha-e.

— The pilgrim's reverence for earth and sky sung through the river-breath of landscape prints.

— The mischievous and the sacred braided together in supernatural visions of Yokai.

Each woodblock print was a seed flung into the future, flowering anew with each generation that dared to lift the fragile paper and look.

The collaborative miracle of woodblock printing—with its carvers, printers, and publishers moving like constellations in shared orbit—ensured that no single hand held dominion over the art. Each print bore the fingerprints of many, an artifact of community, vision, and tenacious impermanence.

Beyond beauty, Ukiyo-e throbbed with social power. It clothed the chonin class in visual dreams, stretched kabuki stages into household shrines, stitched festival nights into everyday fabric. It was fashion. It was rebellion. It was democratized immortality.

Its influence rippled outward, cracking open European art with the fever of Japonisme, threading itself through Impressionist brushstrokes, through the curvilinear madness of Art Nouveau, through the breathing heart of modern graphic design. Ukiyo-e taught the world how to see sideways: to embrace asymmetry, to honor negative space, to dance with the fleeting rather than mourn it.

Today, Ukiyo-e lives not as relic, but as rhythm. It beats in gallery walls, graphic novels, advertising gloss, anime frames. It shimmers at the edge of digital dreams. It teaches that even a fleeting life, captured truthfully, can resist oblivion.

The floating world never sank.

It floated into us.

...