In the hush of a private studio, where light pooled like secrets and the door clicked shut against the world, John Singer Sargent laid his truths bare. Not in speeches, not in letters, but in charcoal and oil. Society knew him by day as the portraitist of satin-skinned aristocrats and gold-flecked glamour. His canvases kissed by opulence. But at night, his brush wandered. It sought muscle, curve, tension. Flesh disrobed and desire unmasked.

He painted not for acclaim, but compulsion. Not to flatter, but to feel. These weren’t studies. They were confessions. Silent admissions of a longing the age refused to name.

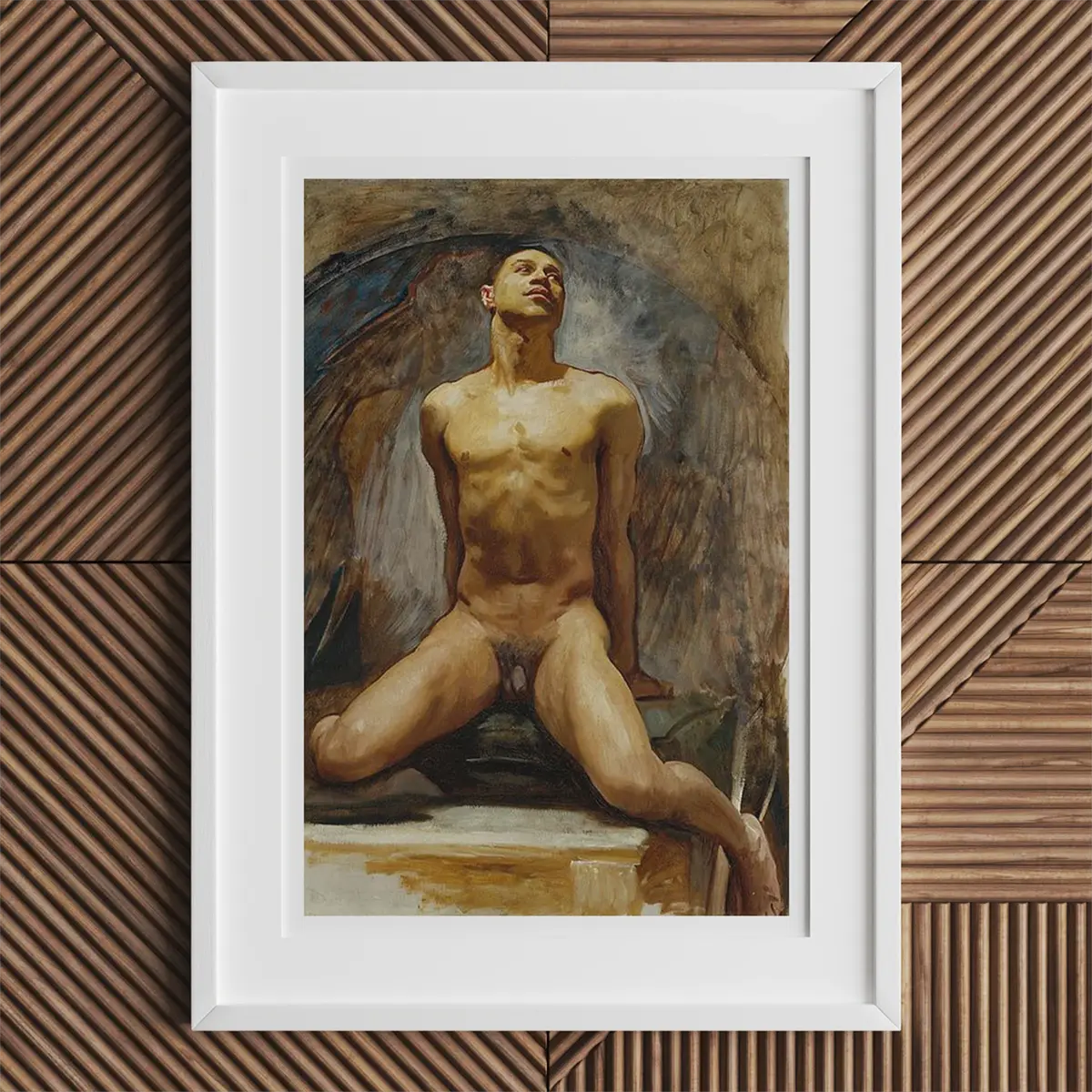

Sargent's male nudes vibrate with tension: classical technique meets aching sensuality, every shadow a withheld moan. No myth to shield their nakedness, no allegory to dull their impact.

To engage these images is to trespass into a room locked for decades, into a desire spoken only in pigment and pose.

Key Takeaways

- A private obsession: Sargent, famed for genteel society portraits, secretly amassed a trove of male nude works, revealing hidden dimensions of desire and vulnerability.

- Historic shifts in masculinity: These artworks echo a Western lineage of male nude representation—ranging from Renaissance idealism to Gilded Age prudery.

- Thomas McKeller’s complex role: The young Black elevator operator became Sargent’s muse and exposed the era’s racial, social, and erotic entanglements.

- Undeniable queer undercurrents: While Sargent’s exact sexuality remains contested, the intimacy in these nudes has earned them a rightful place in the gay canon of fine art.

- Eternal artistic legacy: Once shrouded in privacy, these compelling images now fuel critical dialogues about erasure, identity, and the transformative power of hidden works.

Glimpses of a Past Canon

John Singer Sargent’s male nude art." src="https://tobyleon.com/cdn/shop/files/framed-portrait-man-laurel-wreath-284.webp">John Singer Sargent, Man Wearing Laurels (ca. 1874-80)

John Singer Sargent’s male nude art." src="https://tobyleon.com/cdn/shop/files/framed-portrait-man-laurel-wreath-284.webp">John Singer Sargent, Man Wearing Laurels (ca. 1874-80)

The male nude in Western art has always flickered. Praised in marble antiquity, revived in Renaissance flourishes, then cloaked again beneath Victorian modesty. By the time Sargent arrived, the body was a battleground: admired for strength, feared for sensuality. His era preached discipline, but fetishized health. Gymnasiums, beach scenes, and physical culture clubs exalted the ideal male form. So long as it wasn’t too intimately observed.

Enter Sargent: the dashing traditionalist who moonlit as a chronicler of unspeakable desire. He belonged to two worlds. Commissioned by dukes and doyennes, yet privately sketching young men with bowed heads and parted lips.

These nudes weren’t for public acclaim. They were for silence. Shadowed torsos, outstretched limbs. Drawn not as monuments, but moments. They teeter between classical homage and private longing.

In them, we don’t just see bodies. We feel the friction of a time too polite to name what it craved. Sargent’s canon was quiet, but never coy. It trembled.

The Hidden Catalogue: A Revelation in Charcoal and Oil

John Singer Sargent." src="https://tobyleon.com/cdn/shop/files/framed-impressionist-painting-nude-figures-shore-296.webp">John Singer Sargent, The Bathers (ca. 1917)

John Singer Sargent." src="https://tobyleon.com/cdn/shop/files/framed-impressionist-painting-nude-figures-shore-296.webp">John Singer Sargent, The Bathers (ca. 1917)

Before the internet democratized voyeurism, before curators reclaimed closets of art history, finding Sargent’s male nudes meant entering the underworld of scholarship. These weren’t gallery headliners. They didn’t hang in the salons that made Sargent’s name. They were shadow-works. Silent, unnamed, folded between correspondence or mislabeled in institutional drawers. Discovering them was an act of devotion. Or defiance.

Now, one by one, they’ve surfaced: a whispered catalogue of oil paintings, charcoal studies, graphite sketches, and watercolors. What they reveal isn’t just an artist’s technical mastery. It’s a compulsive, nearly ecstatic return to the male form. Sargent didn’t dabble. He lingered. Returned. Re-rendered. The repetition speaks not of practice, but of pulse.

Look closely and you’ll see two figures orbiting many of these works like moons: Thomas McKeller and Nicola d’Inverno. McKeller’s body, in particular, served as both subject and scaffold—posing nude for allegories that later adorned the Museum of Fine Arts rotunda. In private, he is black, bare, and boldly present. In public, his likeness is translated, whitened, and mythologized. Hercules. Apollo. Psyche.

This slippage is telling. Sargent’s brush honored McKeller’s form, but also erased him. Aesthetic worship collapses into aesthetic appropriation. The drawings are beautiful—but beauty here is tangled, knotted with race, power, and the seductive violence of classicism.

Still, these works hum. In every tensioned thigh and softened jaw, there’s a refusal to look away. They are deeply anatomical—yes—but also profoundly intimate. The charcoal lines throb with care. You can feel the stillness in the studio: the breath between strokes, the vulnerability required to hold a pose when the pose itself is transgressive.

What emerges is not a list of technical accomplishments but a psychic map. These aren’t just bodies rendered—they’re bodies remembered. Desired. Witnessed. Sometimes used. Sometimes honored. Always seen.

Sargent didn’t exhibit these pieces. He hoarded them. Not for shame, necessarily—but for sanctuary.

| Title | Description |

|---|---|

| Nude Boy on the Beach (1878) | A young boy lying nude on a beach in Naples - oil on panel |

| A Male Model Standing before a Stove (1875-80) | A standing male nude model - oil on canvas |

| Reclining Nude (1910) | A reclining male nude - graphite on paper |

| Study of a Seated male nude (1916-21) | Thomas McKeller seated with legs spread - charcoal on paper |

| Study of Two Male Nudes for a Cartouche (1916-21) | Thomas McKeller posing for figures above rotunda roundels - charcoal on paper |

| Study for Eros and Psyche (1916-21) | Thomas McKeller posing as Eros - charcoal on paper |

| Thomas McKeller (1917-21) | Full-length nude portrait of Thomas McKeller - oil on canvas |

| Male Nude Reclining - After the Barbarini Faun (1890-1915) | Reclining male nude - charcoal on paper |

| Reclining Male Nude, Draped (1890-1915) | Reclining male nude with drapery - charcoal on paper |

| Male Nude Seen from Behind (1890-1915) | Standing male nude seen from behind - charcoal on paper |

| Reclining Male Nude (Nicola D'Inverno?) | Reclining male nude, possibly Sargent’s valet - charcoal on paper |

| Study of a Male Nude for Decorative Relief Panel over Staircase (1922-24) | Male nude study for MFA staircase relief - charcoal and graphite |

| Man and Pool, Florida - date unknown | Nude man by a pool in Florida - watercolor |

| Tommies Bathing (1918) | Two nude soldiers bathing - watercolor |

| Massage in a bath house (1890-91) | Two nude men in a bathhouse - oil on canvas |

| Portrait of Nicola D'Inverno (1892) | Portrait of Sargent’s valet - oil on canvas |

Thomas McKeller: Muse in the Shadows

John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Thomas McKellar (ca. 1917-20)

John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Thomas McKellar (ca. 1917-20)

Of all the men who passed through Sargent’s studio, none left a deeper imprint than Thomas Eugene McKeller. Their meeting in 1916—inside the ornate hush of Boston’s Hotel Vendome—had the quiet charge of fate: a white, world-renowned artist steps into an elevator and encounters a young Black man navigating the machinery of a segregated world. One held a brush; the other, his own body.

The dynamics were loaded—race, class, power—but McKeller became more than model. He became conduit. Over nearly a decade, he posed for murals, rotundas, and private studies. In the MFA’s mythological ceiling panels, McKeller’s physicality is recast in alabaster hues, his likeness veiled beneath Greco-Roman idealism. But in the charcoal sketches—those unexhibited, unvarnished moments—he is radiant and real.

Sargent’s full-length nude of McKeller, painted in secrecy and unseen in the artist’s lifetime, feels almost like an apology: the one image where the man isn’t disguised, translated, or transcended—but simply, gloriously himself. It reveals not just anatomy, but a tenderness rarely permitted in public portraiture.

Yet even this homage comes with complication. McKeller’s identity was repeatedly overwritten, used as scaffolding for a myth that excluded him. The portrait is beautiful. The betrayal, embedded.

What remains is the haunting duality of a muse made into both icon and ghost—a figure at once centered and erased, whose presence now forces us to reckon with who gets to be seen, and at what cost.

Racial Dynamics, Queer Readings

John Singer Sargent, Man and Trees, Florida (ca. 1917)

John Singer Sargent, Man and Trees, Florida (ca. 1917)

These paintings whisper. They don’t declare, and they never explain. But in their silence, a world unfolds—one rich with coded desire, erotic tension, and the freighted politics of the gaze. John Singer Sargent never named his longing, never stated his position. And yet, through the slow burn of his male nudes, we sense something undeniable: a hunger made manifest in shadow and skin.

Contemporary queer theory has turned a sharp, loving eye on this secretive trove. Read together, the works become a chorus—fragments of identity that Sargent could never openly claim. There are no manifestos, no confessions. Instead: a curve of the back, a downward glance, a pose too vulnerable to be “just academic.” These gestures became his vocabulary of queerness.

But queerness in Sargent’s work doesn’t float free of history. It’s laced, always, with race and class. McKeller’s transformation from Black man to white marble god is more than aesthetic—it’s a cultural erasure, a soft violence in pursuit of beauty. The mythologies Sargent loved were built on bodies like McKeller’s, but only after those bodies had been stripped of context, of agency, of name.

And still, there is intimacy here. A complexity that resists flattening. We feel, across time, the risk of exposure—for both artist and subject. Legal and social consequences loomed large in the late 19th century, where even suggestion could destroy a career. So these works remained hidden, protected. Treasured, perhaps. Feared.

Today, what once had to be secret has become sacred. These drawings and paintings now live in queer archives, exhibitions, essays. They are claimed, studied, and loved not because Sargent spoke his truth—but because his brush did. And in doing so, he joined a lineage of artists who drew desire not with words, but with want.

Evolving Interpretations and Cultural Significance

John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Nicola D'Inverno (ca. 1889)

John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Nicola D'Inverno (ca. 1889)

As Sargent’s once-concealed male nudes step into the light, they don’t just add footnotes to his biography. They revise it entirely. He is no longer merely the laureate of high society, no longer confined to corsets and cravats, ballroom backdrops and patriarchal pomp. These secret studies of men—unguarded, unidealized—reveal an artist who strayed from grandeur into the granular, from ornament into obsession.

The public-facing Sargent was masterful, yes, but safe. His commissions glowed with opulence, drenched in fabrics that blurred form and figure. But here, in these private works, the fabric falls away. What remains is flesh, unadorned.

The shift is not just stylistic. It’s philosophical. A turn inward. A confession without words.

And institutions have noticed.

The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard have become custodians of these works, preserving them not just as curiosities, but as necessary artifacts of a fuller Sargent. The 2020 exhibition “Boston’s Apollo: Thomas McKeller and John Singer Sargent” reframed the dialogue entirely—spotlighting McKeller not as an accessory to art, but as central to it. As muse, collaborator, and symbol of how race, sexuality, and class can be both veiled and violently visible within a single canvas.

These exhibitions haven’t just shifted curatorial narratives. They’ve sparked conversations across disciplines. About historical erasure, institutional accountability, and the politics of portraiture. In recognizing Sargent’s hidden works, we are also reckoning with the frameworks that once made them unseeable: white supremacy, homophobia, and the fetishization of anonymity.

Because for all their intimacy, these images were silenced. Locked in drawers. Misattributed. Declared irrelevant. Their reappearance is not just a return. It’s a refusal to vanish.

And now, with McKeller’s face and form restored to the center, viewers are asked to look again. To see not just the elegance of line or the mastery of musculature, but the fraught beauty of a man caught in someone else’s myth.

Through this reclamation, Sargent’s private archive has become a public reckoning. One that insists art is never neutral. And beauty, never apolitical.

The Artist’s Veil of Secrecy

John Singer Sargent, Tommies Bathing (ca. 1918)

John Singer Sargent, Tommies Bathing (ca. 1918)

Could Sargent have painted these nudes in full daylight, with signatures bold and brushstrokes unhidden? In another time, perhaps. But in the Gilded Age—an era gilded precisely to mask its rot—he chose the shadows. And maybe, in choosing them, he found clarity. Because secrecy, for all its suffocating weight, can also sharpen intention. It presses meaning into every mark.

Sargent’s veil wasn’t just cultural. It was architectural. His studio was fortress, cocoon, confession booth. Behind its locked doors, a different kind of artistry unfolded. One that didn’t flatter. One that didn’t sell. One that didn’t ask permission. It was here he chased a truth more dangerous than likeness: desire.

The irony? In hiding these works, he may have made them eternal. Their very suppression feeds their seduction. We lean in closer because we were never meant to see them. Their brushstrokes whisper not just beauty, but defiance. They are what happens when longing becomes language. When the artist paints not to be praised, but to be understood by no one but himself.

Yet that very privacy risked their disappearance. For decades, they remained buried. Mistaken for studies, mislabeled, misread. And in this hiding, so much was lost: the queer vocabulary embedded in line, the racial politics entangled in subjecthood, the permission they offered to see—and be seen—without shame.

Now, with institutional eyes finally turned toward them, we’re reminded that concealment doesn’t negate impact. The hush was never silence. It was symphony waiting to be heard.

Sargent’s male nudes are not detours in his practice. They are revelations. Through them, he painted not simply bodies, but boundaries. Testing them, trespassing them, sometimes redrawing them entirely.

And if secrecy fueled their creation, exposure gives them power. To view these works today is not only to uncover what was hidden, but to honor why it had to be. Not to excuse the silence, but to excavate its meaning.

In that excavation, Sargent becomes not just a chronicler of beauty, but of bravery.

Lasting Ripples in the Queer Canon

John Singer Sargent, Man on Beach, Florida (ca. 1917)

John Singer Sargent, Man on Beach, Florida (ca. 1917)

The unveiling of Sargent’s male nudes hasn’t merely revised art history. It’s reshaped queer memory. These images, once sequestered in private collections and museum backrooms, now radiate across exhibitions, essays, and the cultural bloodstream like signals from a century delayed. Their very survival feels miraculous. Their resonance? Immediate.

Though Sargent never labeled himself—never carved identity into biography—his brushwork speaks with the clarity of longing. In every arched spine, in every languid thigh, we sense a gaze not clinical, but aching. These aren’t exercises in proportion. They’re episodes of intimacy. Scenes of stillness trembling with possibility.

And while the 21st-century viewer brings a liberated lens, the art resists simplification. There’s no manifesto here, no overt politics. Only the quiet insistence that male bodies, when rendered with care and curiosity, can become vessels of desire, contemplation, and subversion.

For LGBTQ+ audiences, this is reclamation. A rethreading of ancestral code through pigment. The nudes become more than art. They're proof. Not just of Sargent’s possible queerness, but of a broader, buried tradition: a lineage of artists who translated forbidden feelings into form, who used gesture and light as secret languages when words would have condemned them.

Yet Sargent’s influence isn’t always linear. These works weren’t widely seen until long after his death. Still, their DNA pulses in the photographs of George Platt Lynes, in the paintings of Paul Cadmus and Jared French, in the shadowy erotics of contemporary queer visual culture. Even if Sargent didn’t intend to mentor a movement, his hidden nudes became lodestars. Icons of resistance cloaked in refinement.

Their power also lies in contradiction. They are tender and charged, respectful and transgressive, aesthetic and erotic. This ambiguity makes them timeless. They offer no answers, only the exquisite discomfort of being seen and not seen. And it’s that in-betweenness that resonates most deeply now. In a world still wrestling with visibility, legibility, and who gets to own their reflection.

To view Sargent’s male nudes is to witness an artist walking a tightrope between what was permitted and what was necessary. Between survival and expression. Between the closet and the archive.

And it’s in that balancing act, that exquisite peril, that his legacy finds its fiercest clarity.

A Legacy of the Unspoken

John Singer Sargent, Study of a Male Nude Figure (ca. 1920)

John Singer Sargent, Study of a Male Nude Figure (ca. 1920)

To stand before one of Sargent’s male nudes is to enter a room without sound but thick with atmosphere. Every line hums. Every shadow tightens like breath held too long. These works don’t shout—they pulse. Not with spectacle, but with intent. They beckon with the gravity of the unspoken.

The intimacy is unmistakable. The men—naked not just in form, but in spirit—reveal something more than anatomy. They are tender, tense, withheld. These are not passive studies. They are negotiations: between artist and model, desire and decorum, privacy and posterity.

Sargent never offered interpretation. No titles to suggest meaning, no letters confessing motive. But the drawings and paintings say enough. They murmur across time: about what it meant to want, to witness, to render without permission. About the ache of proximity, the cost of longing that had no name in polite society.

In today’s landscape of identity politics and representational reclamation, these images carry fresh weight. They remind us that art has always been a site of concealment and confession. That queerness, like pigment, can be layered. Built stroke by stroke, implication by implication. What Sargent couldn’t say aloud, he folded into the musculature of his subjects, into the downcast eyes and curved hips and vulnerable backs.

And in that folding, something remarkable occurred: resistance through restraint. His secret nudes are not acts of cowardice, but of coded defiance. They claim space in the canon not because they were allowed, but because they endured.

Now, as queer artists and scholars look back, Sargent’s hidden portfolio becomes a beacon. A map of how much can be said when nothing is said directly. A lesson in surviving through subtext. In leaving breadcrumbs for those who’d come after, hungry for proof that their hunger was not new.

In the quietude of his studio, Sargent didn’t just draw bodies. He archived longing.

And that archive, once buried, now sings.

Reading List

Fairbrother, Trevor J. "A Private Album: John Singer Sargent's Studies of Nude Male Models." Arts Magazine 56, no. 4 (December 1981): 70-79.

Fairbrother, Trevor J. John Singer Sargent: The Sensualist. Exh. cat. Seattle Art Museum/Yale University Press, 2000.

Fisher, Paul. The Grand Affair: John Singer Sargent in His World. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022.

Hirshler, Erica E., Nathaniel Silver, Trevor Fairbrother, Paul Fisher, Nikki A. Greene, Lorraine O'Grady, Casey Riley, and Colm Tóibín. Boston's Apollo: Thomas McKeller and John Singer Sargent. Exh. cat. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2020.

Ormond, Richard. John Singer Sargent: Complete Paintings, Volume 1: The Early Portraits. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

Ormond, Richard, and Elaine Kilmurray. John Singer Sargent: Figures and Landscapes, 1900-1907. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012.

Silver, Nathaniel. "Thomas Eugene McKeller, John Singer Sargent, and Isabella Stewart Gardner." Inside the Collection (blog), Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, May 12, 2020. https://www.gardnermuseum.org/blog/thomas-mckeller-john-singer-sargent.

Tate. "'A Nude Boy on a Beach', John Singer Sargent, 1878." https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/sargent-a-nude-boy-on-a-beach-t03927.

Tate. "John Singer Sargent 1856–1925." https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/john-singer-sargent-475.

Wikimedia Commons. "Category:Paintings of nude men by John Singer Sargent."(https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Paintings_of_nude_men_by_John_Singer_Sargent).