This protean identity poses a labyrinth for art historians seeking to map his oeuvre, but it also reveals Koson’s adaptability: he was less concerned with static signature than with sustaining a living dialogue between brush, block, and audience.

Initially dedicated to painting in the Nihonga style—a revitalization of classical Japanese painting traditions—Koson eventually turned back to the older medium of woodblock printing, a shift that mirrored broader cultural oscillations between preservation and innovation. His move from painting to prints was not ideological. It was tactical.

Prints, especially those calibrated to Western collectors’ longing for the “authentic” Japan, offered a broader, hungrier market. And Koson, always attuned to the rhythms beneath the surface, adjusted his sails accordingly.

His partnership with Watanabe Shōzaburō—soon to be the most influential figure in the burgeoning Shin-hanga movement—would not merely redirect his career. It would etch Koson’s birds and blooms into the transpacific memory of Japanese art.

This pivot from brush to block, from war scenes to plumage and ripple, was not an abandonment of depth. It was a rechanneling: a strategic return to nature as an unassailable constant, even as empires rose and crumbled around him.

Emergence of the Shin-hanga Movement

By the early 20th century, the lifeblood of ukiyo-e—those floating worlds of courtesans, kabuki players, and whispered alleyways—had thinned almost to stillness. Industrial inks, photographic prints, and Western lithography gnawed at woodblock’s dominion. What once crowned the cultural skyline now sagged behind glass in the rare book rooms of Parisian collectors.

Japan, burning with the fever of modernization, seemed prepared to let its own aesthetic inheritance gutter out.

Into this fragile twilight strode a pragmatist disguised as a dreamer: Watanabe Shōzaburō (渡辺 庄三郎).

Where others saw decline, Watanabe saw ignition.

Around 1915, he began orchestrating what would soon shimmer into being as the Shin-hanga ("new prints") movement—a resuscitation effort that clutched tradition in one hand and welcomed selective Western technique in the other.

Shin-hanga did not propose rupture. It proposed seduction.

Unlike the more anarchic sōsaku-hanga ("creative prints") movement—where artists carved, printed, and published their own visions—Shin-hanga retained the old ukiyo-e model: a quadripartite collaboration between artist, block carver, printer, and publisher. Each role remained distinct, each artisan crucial.

It was a model rooted not in individualistic bravado but in an orchestrated confluence of mastery.

And yet, into this feudal lattice, Watanabe smuggled modernity:

— Perspective borrowed from Renaissance vanishing points.

— Shading that wrapped bodies in atmosphere rather than flattening them into silhouettes.

— Mood that lingered like the blurred afterimage of Impressionist gardens.

Prints that once floated above reality like ink-dreams now anchored themselves in a tangible world of twilight streets, mist-wet rice fields, and faces seen through rain-slicked windowpanes.

Thematically, Shin-hanga remained loyal to Japanese subject matter—its revered quadrants:

Yet these were not frozen echoes. They breathed differently now. Light didn't just gild the scene; it infiltrated it, weighted it.

Western audiences, starved for romantic visions of an "unchanging" Japan as their own empires sprawled, became Shin-hanga's hungriest patrons.

The irony rippled like pondwater: prints rooted in cultural nostalgia, reformulated using foreign techniques, exported to foreign shores desperate to admire the "authenticity" they themselves had helped to destabilize.

Thus Shin-hanga’s success was never purely aesthetic. It was geopolitical: a soft transaction of memory, mythology, and modern technique.

In this collaborative dance of vision and translation, Ohara Koson found an ecosystem exquisitely suited to his skills. His birds, his blooms, his mist-threaded seasons—all could slip between worlds without fracture.

Koson, in joining Shin-hanga, wasn’t abandoning tradition. He was proof that tradition, if spoken in the right dialect of light and ink, could survive the long violence of history’s march—and even enchant its invaders.

In a Japan where trains outpaced monks and cities swallowed their own rivers, the Shin-hanga movement became a necessary paradox: Innovation disguised as memory, globalization disguised as preservation.

And in its delicate carpentry of old and new, Koson’s art found not just survival—but amplification.

Ohara Koson and the Kachō-e Tradition

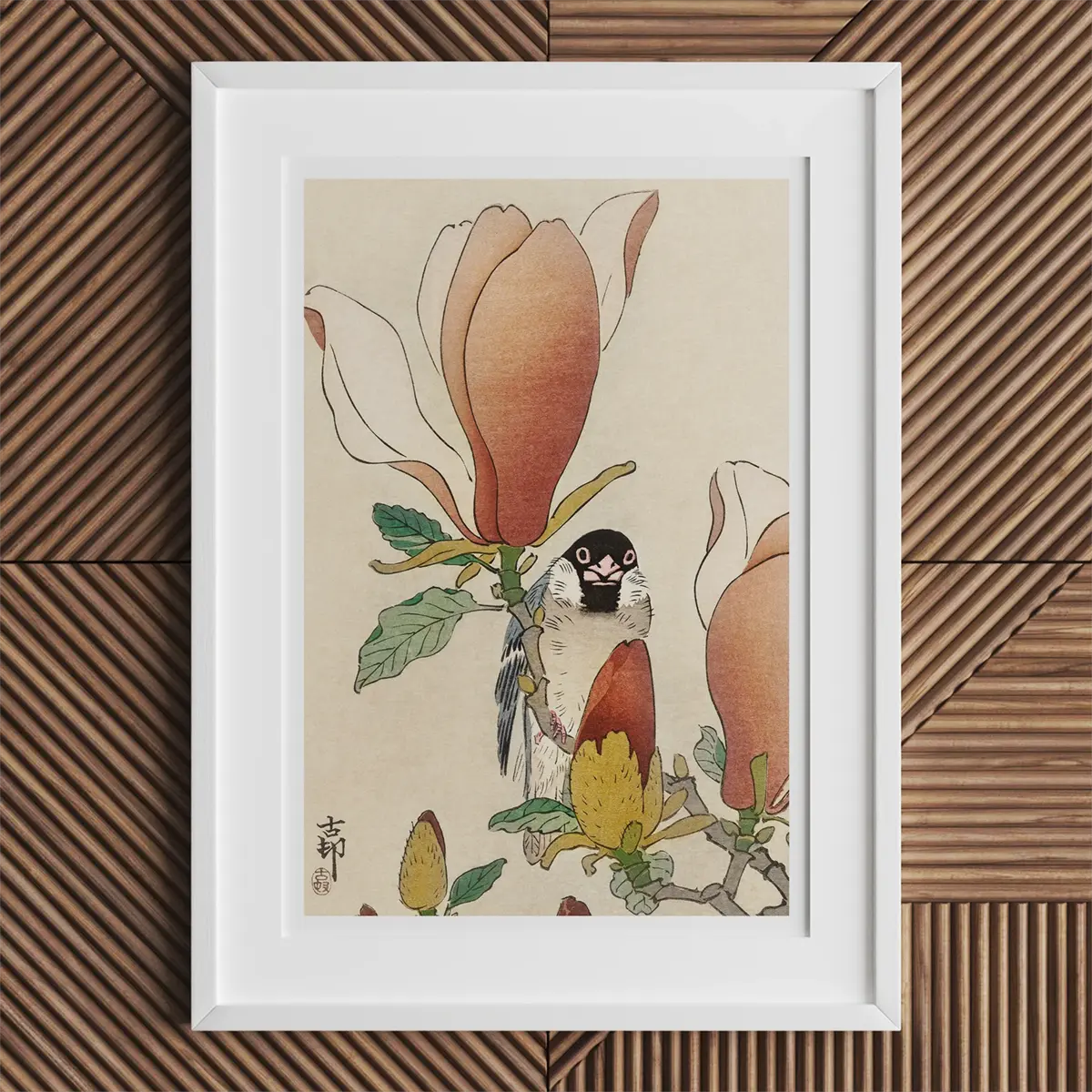

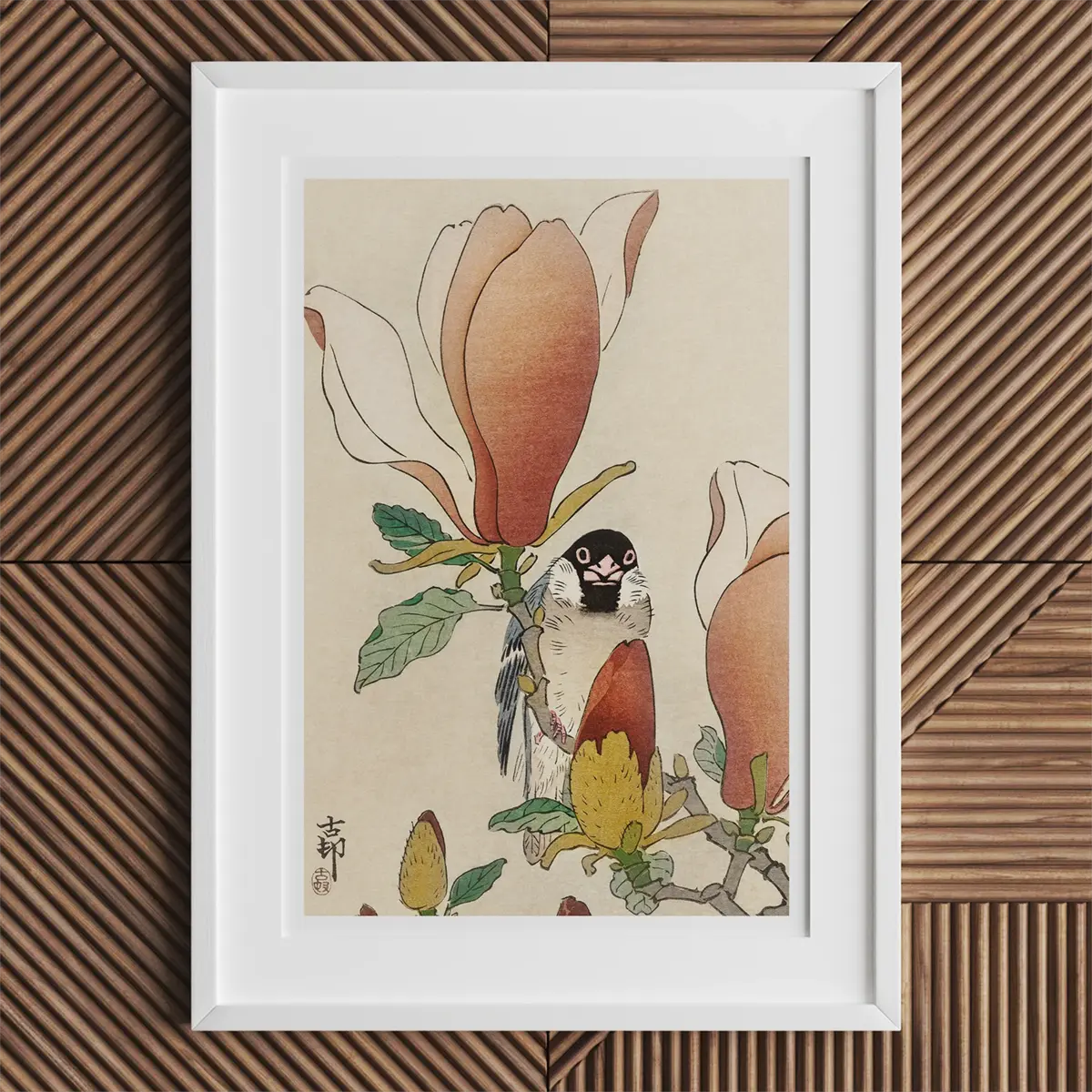

Before cameras trapped seasons in silver nitrate, before scientific drawings categorized wings and petals into sterile nomenclature, there was kachō-e: the art of breathing life into birds and blossoms through brush and block, the old Japanese language for honoring nature’s smallest ceremonies.

Rooted in Chinese artistic traditions yet sharpened to a fierce particularity on Japanese soil, kachō-e did not concern itself with botanical accuracy for its own sake. It spoke instead to the spirit inhabiting plum blossom and heron wing, to the ephemeral kinship between a crow’s silhouette and the slow, sinking moon.

When Ohara Koson pressed his devotion into this genre, he was not reviving a relic.

He was listening to an ancient frequency still thrumming under the concrete skin of modern Japan.

Kachō-e had always been a mode of seeing: a way of articulating the interconnectedness of all things, the fleeting arrangements of season, wind, water, and life. Unlike Western natural history, which often pinned specimens to velvet under glass, Japanese kachō-e charted the living momentum between creatures and their worlds—where the movement of a sparrow's wing could ripple unseen through entire forests of metaphor.

Koson’s fidelity to this tradition was absolute, yet never rigid.

He adorned his prints with a deep symbolic vocabulary, familiar to any who had grown up tracing seasons by the migrations of cranes or the falling of persimmons:

Cranes, arcing across icy skies, bore the gravitas of longevity and imperial blessing.

Owls, their feathers breathing against winter branches, murmured of wisdom folded in darkness.

Peonies, so heavy with bloom they seemed to bow under their own beauty, conjured prosperity and decadent fortune.

In Koson's hands, a solitary crow on a barren limb became more than ornithological study: it became a meditation on solitude, on survival stitched into silhouette.

His lines, at once spare and saturated, conveyed not just the outward form but the inward trembling of life—fragile, stubborn, miraculous.

He didn’t just paint birds and flowers. He caught the world mid-breath, before it knew it was being watched.

Koson’s allegiance to kachō-e within the Shin-hanga movement was a deliberate act of aesthetic diplomacy: He brought nature’s intimacy into a modern context without betraying its timeless grammar.

Western collectors, accustomed to paintings of nature as passive scenery, were enthralled by the density of meaning packed into these seemingly simple compositions. Every leaf a cipher. Every feather a parable.

Koson’s work offered an accessible entry point into Japanese philosophy for foreign audiences: a glimpse into a worldview where human life and nature’s cycles are not rivals but reflections.

In crafting these tender, razor-sharp images, Koson didn’t merely preserve kachō-e.

He recalibrated it—subtly, almost invisibly—so that even in a world of steamship smoke and electric lamplight, a crane could still carry eternity across a blank page.

Through Koson's eye, the delicate armature of tradition remained intact, but flexed to accommodate a new century’s light. His bird-and-flower prints became living hinges between epochs: unshaken in spirit, yet elastic in form.

Nature, once again, survived innovation by slipping its roots deeper underground—and in Koson’s prints, it flourished in silence and color.

Koson's Technical Style and Innovation

In an age when speed became the measure of progress, Ohara Koson doubled down on slowness—the cultivated patience of pigments bleeding into paper, the negotiation between blade and woodgrain, the whispered agreement between carver’s knife and the breath of a crane’s wing.

Koson’s artistic arsenal was forged not merely from vision but from craftsmanship so exacting it bordered on conjuring.

His designs began with a draft: brush moving like a reed in river-current rhythm, finding form not by dictating it, but by coaxing it from stillness. Yet Koson’s genius was not limited to design alone. He possessed a rare, granular understanding of every stage that followed—the carving, the inking, the pressing—all of it choreographed to translate vision into permanence without fracture.

The printing process itself remained an intricate ballet of collaboration—a Shin-hanga hallmark.

Koson would conceive the blueprint; master carvers would render it into wooden matrices with scalpels of surgical dexterity; seasoned printers would ink and press each sheet of hand-made washi paper, attentive to temperature, humidity, and the attitude of each grain.

Only through this disciplined relay could Koson’s breath-light compositions achieve their uncanny fidelity.

Among Koson’s signature techniques was an exquisite mastery of bokashi—the art of color gradation that allowed prints to shift from mist to moonlight within the width of a feather.

Through bokashi, sunsets bled into lakes without seam; cranes emerged from fog like memories; snowfields blurred against empty skies with a breathless logic only nature—or Koson—could author.

The material choices further deepened the resonance of his prints.

Koson often favored natural pigments, pulled from the ancient apothecaries of Japan: minerals ground to powder, plants boiled to stain. His palette was not an affectation—it was an act of fidelity to earth and history, even as mass production elsewhere surged forward with chemical shortcuts.

His use of washi, often drawn from the resilient fibers of the mulberry tree, ensured that each print carried a living texture—a subtle flex of organic memory that synthetic paper could never counterfeit.

Koson’s engagement with Western aesthetics did not manifest as capitulation. It surfaced subtly: a tension of perspective here, a realism of anatomy there, a shaft of light behaving with the diffused insistence of an Impressionist afternoon.

Yet even when borrowing Western techniques, Koson funneled them through an Eastern sensibility: not depicting nature as something observed from a distance, but as something breathed in, lived inside.

This synthesis—of rigorous Japanese craftsmanship and quiet Western realism—allowed Koson’s works to vibrate across continents without rupture. They spoke fluently in two artistic dialects without losing their native accent.

The collaborative structure of Shin-hanga, which some critics deemed retrograde in an age lionizing individual genius, was for Koson a perfect armature: a system where mastery could pool, concentrate, and ignite.

His artisans were not anonymous laborers—they were essential conspirators in the alchemy.

Every precision-cut featherline, every breath-thin wash of color, every crisp silhouette against a fogged backdrop was the result of many hands threading one vision.

Koson’s technical fluency—his obsession with detail, his sensitivity to materials, his exacting standards in collaboration—allowed him to create prints that feel both ancient and urgent, tactile and ephemeral.

Every Koson woodblock is a fingerprint of collective excellence, a negotiation between mastery and humility.

The crane lifts its wings; the carp stirs the water; the maple leaf drifts.

Yet behind these still moments lies an architecture of skill so intricate that it disappears into its own perfection.

Koson’s innovation was not loud. It did not advertise itself. It slipped into the bloodstream of the print quietly, like the first frost threading an autumn branch—transforming everything, leaving no visible trace of effort, only awe.

Symbolism and Cultural Resonance

Beneath the delicate cartilage of Ohara Koson’s bird wings and peony blossoms runs an architecture of meaning, invisible to the untrained eye but dense enough to buckle entire histories.

Koson didn’t paint nature for the sake of decoration. He encoded it.

Each element in his prints—feather, branch, ripple, frost—is a cipher stitched into centuries of Japanese cultural memory.

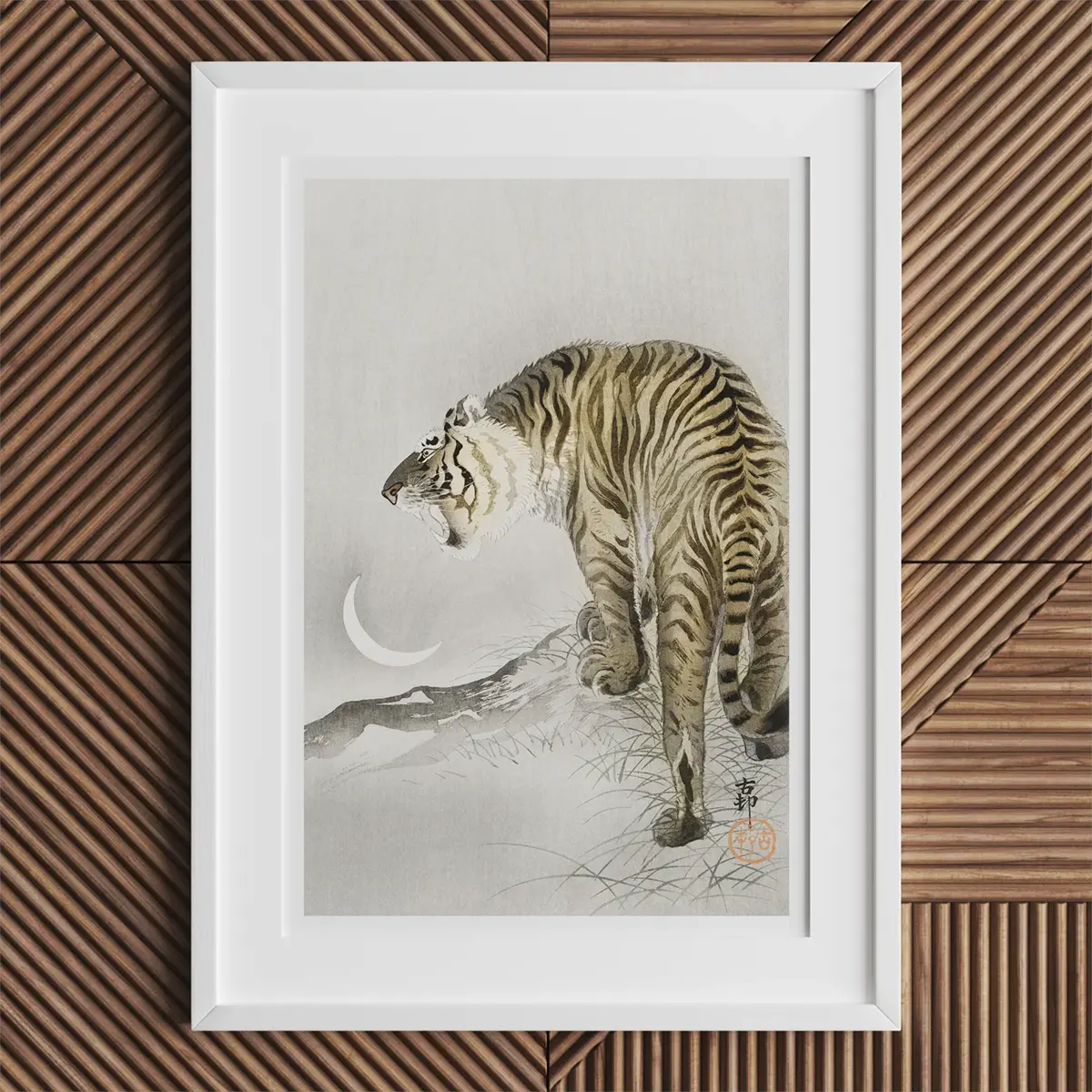

The crow that settles on a barren branch under a fattened moon doesn't just convey winter solitude; it gestures toward the inescapable melancholy that drips through Buddhist notions of impermanence.

A peony, heavy with lush, unfolding petals, isn’t merely opulent—it signifies a kingdom where abundance teeters dangerously close to rot.

His use of seasonal markers—the saffron shock of autumn leaves, the skeletal reach of winter twigs, the pale urgency of cherry blossoms—maps not just months, but moods.

Seasonality, for Koson’s Japan, was less calendar than philosophy: a tender fatalism that framed every bloom and every fall as part of an exquisite, inescapable choreography.

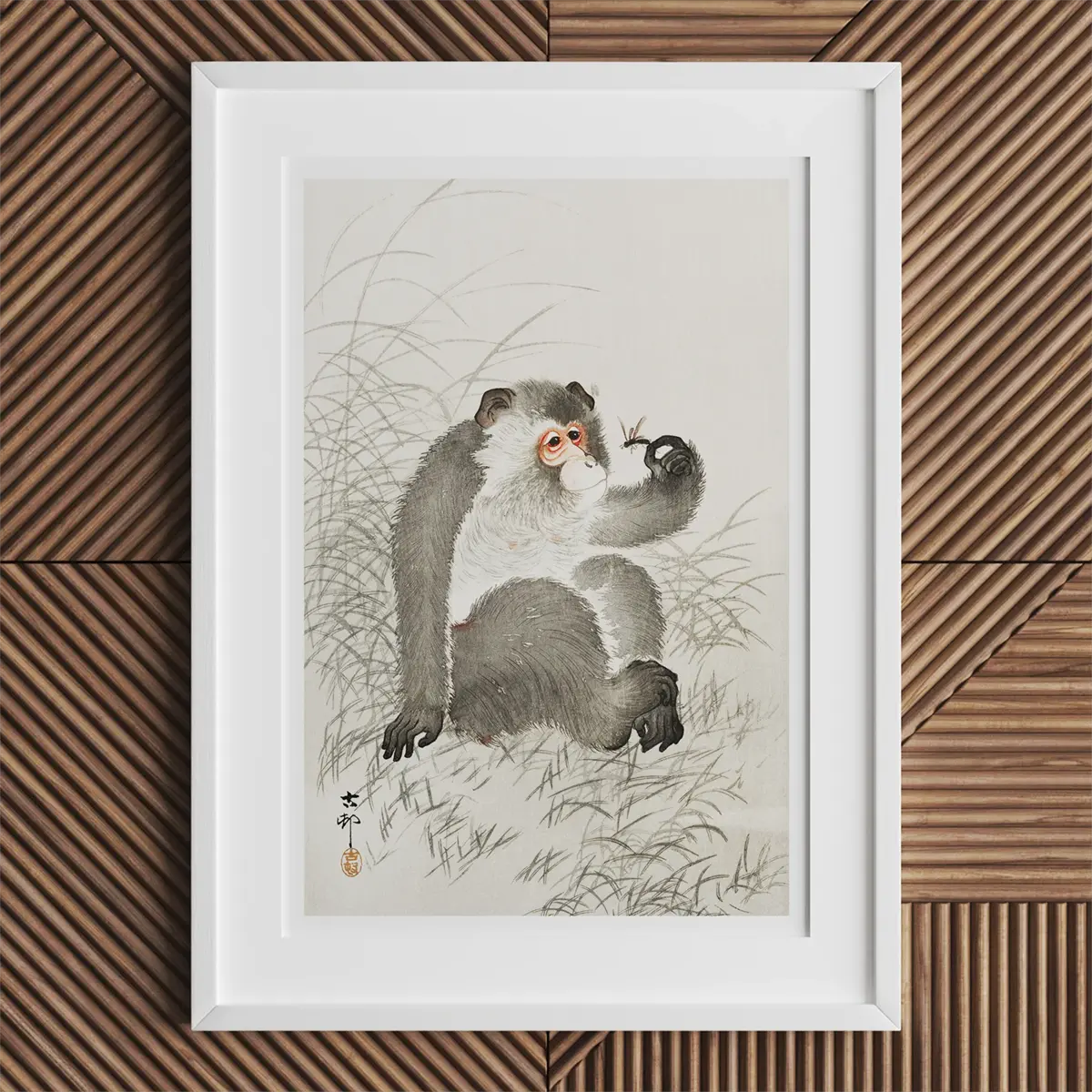

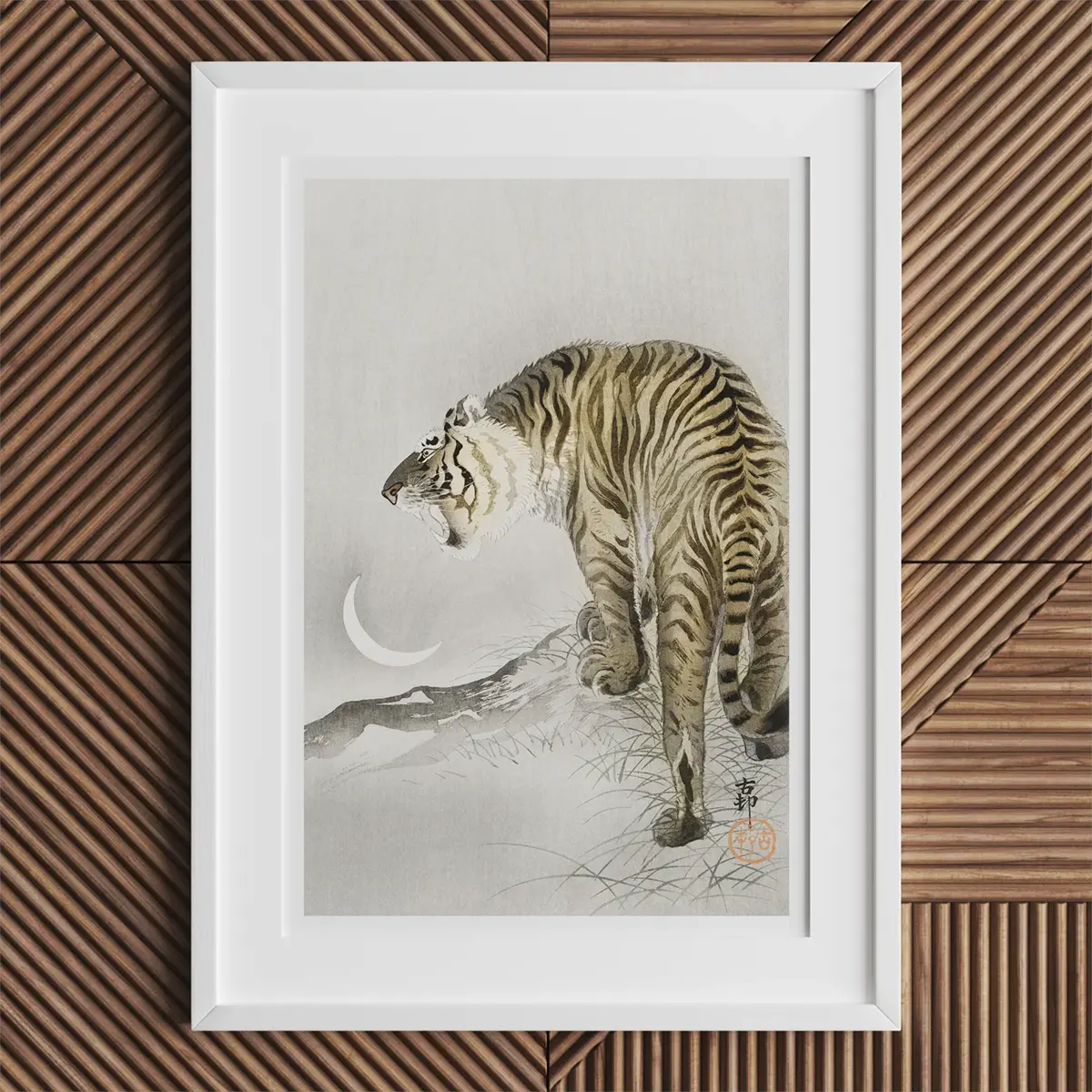

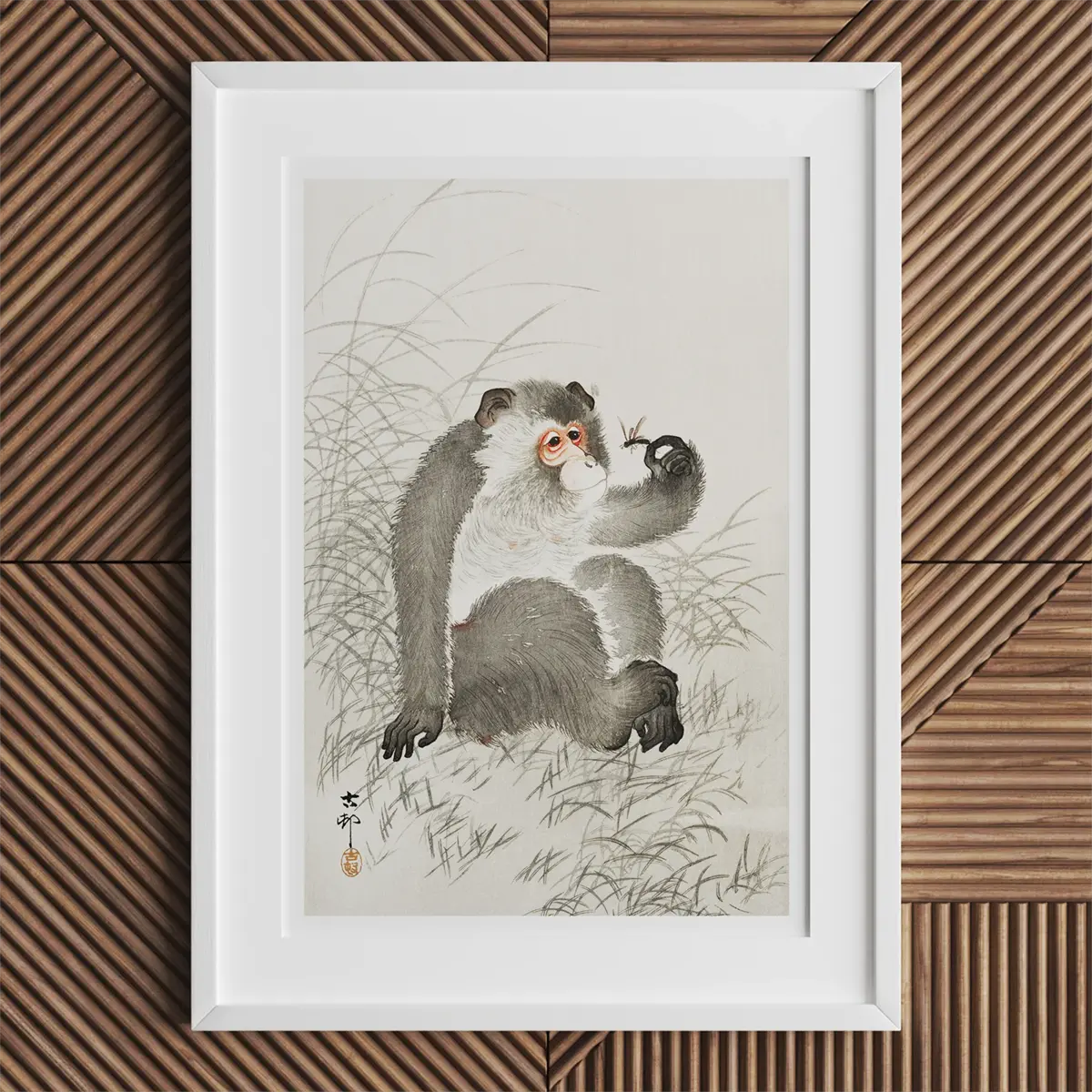

The animals he chose were never neutral either.

Cranes, with their glacier-white wings, carried the freight of longevity, sacredness, and imperial grace.

Owls, perched like contemplative monks, bore the quiet weight of sagacity and nocturnal vigilance.

Monkeys, sometimes scrambling across riverbanks or clinging to rain-slicked branches, embodied both cleverness and poignant echoes of humanity’s own restless heart.

To engage with Koson’s work is to move through an unseen glossary: each botanical detail, each animal gaze, each arrangement of branch and fog laden with references deeper than visual pleasure.

Yet his prints never collapse under the weight of symbolism. They float—deceptively simple at first glance, but expanding inward with the patient gravity of tidewater.

This layered richness found particular traction among Western collectors, whose hunger for the “exotic” often masked a yearning for art that operated under rules different from their own.

Koson’s work offered them a portal into a culture where nature wasn't backdrop but protagonist, where every season was a philosophy, every petal a lesson in mortality.

For Western viewers, accustomed to landscapes as mere scenery or flora as aesthetic garnish, Koson’s prints delivered something disorienting: a world where nature wasn't just observed—it was known, mirrored, mourned, and celebrated all at once.

The recurring motifs in his work—graceful cranes against burning skies, solitary crows hunched under waning moons, maples bleeding red against the season’s fade—acted almost as ideograms: compressed narratives that bypassed linguistic barriers to hit some deeper chord of understanding.

By embedding these symbols so deftly into his compositions, Koson allowed his art to vibrate across cultural thresholds without losing its native cadence.

It was not a translation; it was an invitation—to feel, if not to fully decipher.

Koson’s genius lies in that shimmering threshold: his images feel intimate yet inscrutable, accessible yet charged with unseen depth.

The natural world, under his brush, becomes a site of memory, prophecy, and meditation—not frozen in time, but trembling slightly at the touch of history’s wind.

He mapped not just the world outside the window, but the inner seasons of the human heart.

Every feathered hush of motion, every glistening petal, every soft press of ink onto paper whispers the same thing: the world changes, the heart breaks, the seasons turn—and still, somewhere in the margins, beauty persists.

Collaborations with Publishers

No artist moves alone across the architecture of history. Each brushstroke that endures does so because somewhere—quietly, industriously—another hand steadied the paper, carved the block, bankrolled the dream.

For Ohara Koson, the corridors of artistic immortality were lined not just with pigment and wood, but with publishers whose ambitions braided into his own.

In the nascent years of his career, Koson tethered himself to Kokkeidō and Daikokuya, established houses that trafficked in the potent imagery of empire and expansion. His war triptychs—vivid evocations of the Russo-Japanese War—found their inked afterlives through their presses, feeding both nationalist sentiment and an increasingly global curiosity about Japan's rising military and cultural power.

Yet it was his later collaboration with Watanabe Shōzaburō that would crystalize Koson’s true epochal importance.

Around 1926, as Tokyo still coughed up ash and splintered timber from the catastrophic Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, Watanabe was not merely rebuilding his publishing empire—he was redrawing the cartography of Japanese art itself.

Watanabe needed artists who could channel tradition without embalming it, who could seduce Western markets without pandering to them.

Koson, with his unswerving dedication to kachō-e and his elastic adaptability to subtle Western visual techniques, became indispensable.

It is through Watanabe’s shrewd machinery—his distribution networks, his relentless exhibitions abroad, his keen calibration of Japanese nostalgia for Western appetite—that Koson’s birds first unfurled their wings across Europe and America.

Under this partnership, Koson signed his prints as Shōson, a quiet renaming that stitched his new identity into the fabric of global commerce without severing it from its roots.

The relationship between artist and publisher was not frictionless, but it was ferociously productive: Koson provided images of feather and blossom that clung stubbornly to memory, and Watanabe wielded the infrastructure to move them across oceans.

For a brief window between 1930 and 1931, Koson also collaborated with Kawaguchi, signing works as Hōson—a flicker of divergence, a minor eddy in the river of his career.

These prints, though fewer in number, testify to Koson’s tactical awareness: the willingness to diversify without diluting his aesthetic commitment.

Each of these publishing relationships left distinct fingerprints on Koson’s oeuvre:

Early prints under Kokkeidō and Daikokuya aimed at martial spectacle.

The bulk of his mature kachō-e masterpieces flowering under Watanabe’s strategic umbrella.

A short, intriguing interlude with Kawaguchi, whose reach, though less sweeping, still expanded the genealogical branches of Koson's output.

Yet it was Watanabe’s vision—his acute sense that the Western hunger for Japan was not sated by swords and samurai, but by delicate, aching depictions of the natural world—that turned Koson from a gifted practitioner into a cultural emissary.

The aftermath of the Great Kantō Earthquake had swept away much of Tokyo's artisan class, its fragile infrastructures of artistic production.

In rebuilding, Watanabe recognized that Japan’s visual legacy could either fossilize or bloom again through careful hybridization.

Koson, like a crane lifting itself from frozen marshland, rose into this new air.

His publishers did not merely reproduce his work. They magnified it, stratified it, gave it velocity across time zones and cultural hemispheres.

Without Kokkeidō and Daikokuya, Koson might have remained a regional figure. Without Watanabe, he might have been a footnote.

Because of them, he became a bridge: an artist whose compositions of plum blossom, kingfisher, and snow-laden reed now hang in collections where the air still trembles faintly with the memory of old seasons, old names, old agreements made between artist and merchant, vision and ledger.

Koson's collaboration with these publishers wasn’t a compromise. It was the apparatus that let his art outlast both the wars it depicted and the earthquakes that shattered the streets beneath his feet.

It was business, yes. But it was also survival. And through it, the crane still flies.

Global Recognition and Continuing Influence

Across oceans, Ohara Koson’s birds took flight long before his name was stitched securely into the Japanese canon.

In Europe and the United States—lands more familiar with crows as omens and cranes as myths—his prints arrived not as relics but as dispatches from a culture still imagined as delicate, untouched, and dreamlike.

It was through Western hunger for "authentic" Japanese art—framed, ironically, by the very distortions of colonial fascination—that Koson’s work found early acclaim.

His prints shimmered behind glass at the Toledo Museum of Art exhibitions in 1930 and 1936, marking critical moments when American collectors, curators, and aesthetes began assembling a vocabulary of Japan that owed more to Shin-hanga than to actual contemporary Tokyo.

In these hallowed halls, Koson’s birds sang across languages without need for translation.

Private collections, too, swelled with his works: John D. Rockefeller Jr., heir to industrial fortunes and patron of international art, counted Koson among his acquisitions—a quiet acknowledgment that beauty, meticulously rendered, could breach even the thickest walls of oil and empire.

Koson’s global embrace was undeniable. Yet within Japan, his fame remained spectral—an echo heard mainly among publishers, artisans, and a handful of collectors attuned to the shifting tectonics of national identity.

At home, the Shin-hanga movement itself was viewed with a mixture of admiration, suspicion, and indifference.

Critics who valorized pure Nihonga painting or avant-garde experimentation often regarded Shin-hanga as a polite compromise—a movement too willing to tailor its beauty to foreign palates.

Thus, Koson’s luminous cranes and cherry blossoms often flew beneath the notice of the domestic establishment, even as they nested in parlors, libraries, and museums across Europe and America.

Yet influence does not require permission.

Koson’s prints embedded themselves in the visual DNA of global Japanese aesthetics—setting standards for how nature’s ephemerality could be rendered, how tradition could murmur through modernity without dissolving.

Artists both in Japan and abroad, conscious or not, drew from Koson's mastery:

His techniques of bokashi—soft gradients of light and fog—reappeared in modern design and contemporary illustration.

His precision of line, his ruthless editing of unnecessary detail, informed later generations of printmakers seeking to balance abstraction with intimacy.

Today, echoes of Koson’s compositions ripple across multiple mediums:

- In the stark minimalism of graphic design.

- In the calibrated hush of contemporary nature photography.

- In the rewilding of digital animation where a single falling petal carries the narrative weight of an entire season.

Koson’s influence, like a migrating flock barely glimpsed against a grey sky, remains pervasive yet elusive—present in the gestures of others, refracted through new sensibilities, reborn across disciplines.

That his homeland initially overlooked him only magnifies the paradox at the heart of Shin-hanga itself: the art of preservation made legible only through the gaze of the outsider.

Koson understood this tension instinctively. He did not fight it. He painted right through it—each print a quiet act of survival, of transmutation, of allegiance to beauty in a century tilting dangerously toward forgetting.

Legacy

When Ohara Koson slipped from the world in 1945, the war had already begun remapping the bones of nations, and the fine thread of his art seemed, for a time, too delicate to survive the din.

His name, like so many who labored not under manifestos but under the private discipline of beauty, faded into the background noise of recovery and redefinition.

Yet threads, even when buried, remember how to bind.

In the slow, deliberate decades that followed, Koson’s work re-emerged—not as nostalgia, but as necessity.

The same cranes, the same kingfishers, the same fall of maple leaves that once sold briskly to foreigners now demanded reappraisal by a Japan eager to rethread its own artistic lineage without apology or distortion.

Major exhibitions at institutions such as the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Minneapolis Institute of Art reintroduced Koson’s oeuvre not as decorative whimsy but as vital documentation of an aesthetic mind negotiating rupture without surrender.

His prints were no longer simply admired for their meticulous beauty; they were read as acts of strategic cultural preservation, as dialogues between tradition and innovation, as blueprints for survival in a century engineered to erase.

The scholars followed:

- New studies mapped the changes in his signatures, traced the migrations of his designs across continents, parsed the symbolic matrices embedded in his compositions.

- Koson was no longer a minor craftsman.

- He was revealed as a cartographer of resilience—charting how art could stay supple even as the currents of empire, modernization, and war sought to tear it apart.

His dedication to kachō-e, once viewed by some as quaint, is now understood as radical.

At a time when mass culture pushed toward speed and abstraction, Koson refused the seduction of forgetting.

He bet his entire practice on the slow miracle of observation: the gloss of a feather against twilight, the shiver of a reed in first frost, the brittle gleam of a camellia in snow.

Today, his influence can be felt far beyond the curated walls of museums.

Contemporary artists, conservationists, illustrators, and designers draw from his techniques, his philosophies, his stubborn fidelity to the details of a natural world still trembling at the margins of human attention.

Koson’s birds and blossoms did not fossilize into the past. They have continued to flutter, perch, molt, and bloom in the imaginations of those who understand that fidelity to the ephemeral is one of the rarest, fiercest acts of art.

In the story of Japanese woodblock printing—where innovation often comes disguised in the robes of remembrance—Koson now stands firmly as a necessary figure: an artist who refused to surrender the small truths even as the big truths convulsed around him.

Through his cranes that still arch across empty skies, through his willows that still bow into unseen water, Koson tells the old story the only way it survives: by rendering it visible again, and again, and again.

Not by clinging to the past, but by stitching it—deliberately, fiercely—into the living breath of the present.