In the kaleidoscopic theater of Japan’s Edo period, Kitagawa Utamaro (喜多川歌麿) stood as both architect and poet of the ephemeral, chiseling fleeting beauty into permanence with a woodblock's bite and a brush’s caress.

His ukiyo-e prints did not merely depict women—they distilled them, rendering each curve of the wrist, each downward glance, each secret thought shimmering behind heavy lids, into a new visual lexicon of grace.

Utamaro’s women are not ornaments; they are tectonic forces dressed in silk, vessels of the floating world’s ache for fleeting pleasure and unsolvable mystery.

Through his hands, Edo's vibrant fever dreams—the teahouses, the licensed quarters, the shadow-play of love and loneliness—found crystalline form.

His prints, often powdered with mica to mimic the glimmer of lamplight on skin, carried the heat and hush of an era where beauty was both a currency and a religion. Utamaro sculpted a genre within a genre: bijin-ga, portraits of beautiful women so alive they might exhale across the centuries.

More than an artisan, Utamaro became a mirror—and a magnifier—of the era’s obsessions, crafting images that resonated far beyond Japan’s shores. As Japonisme swept across 19th-century Europe, his influence bled into the dreams of artists like Monet and Cassatt, igniting revolutions in light, form, and emotional immediacy.

Today, Utamaro’s vision remains undiminished: his prints are constellations within the vast night sky of world art, reminders that beauty’s transience is precisely what grants it its devastating power.

Key Takeaways

-

Kitagawa Utamaro, a towering figure of Edo-period ukiyo-e, is celebrated for immortalizing the ephemeral beauty and emotional resonance of women through his masterful woodblock prints.

-

His pioneering focus on bijin-ga—portraits of beautiful women—revolutionized the genre by capturing not just surface elegance, but intimate psychology and fleeting emotions.

-

Utamaro’s technical innovations, including the use of gauffrage (embossing) and mica powder (kirazuri), elevated ukiyo-e prints from popular ephemera to luminous works of art imbued with tactile and visual richness.

-

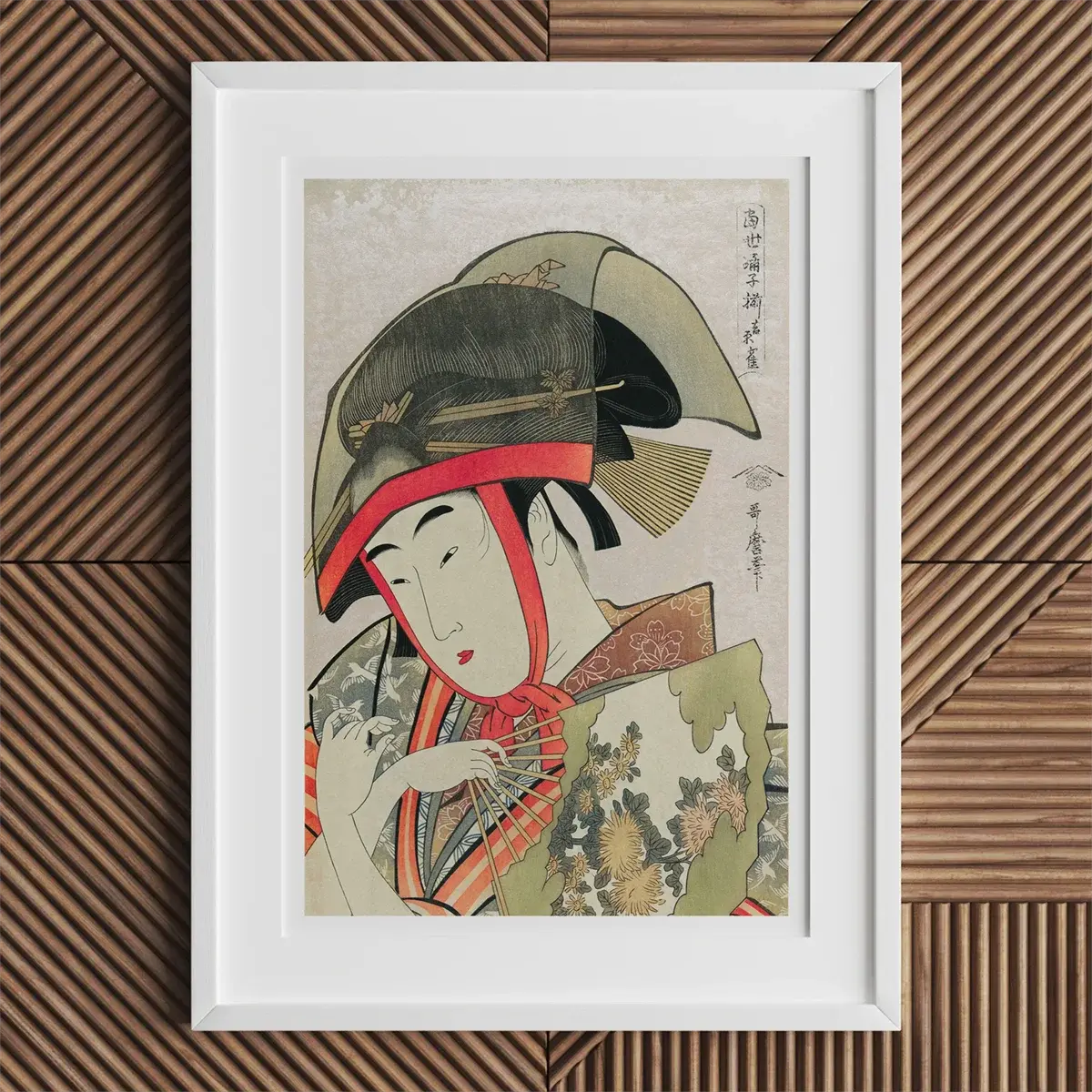

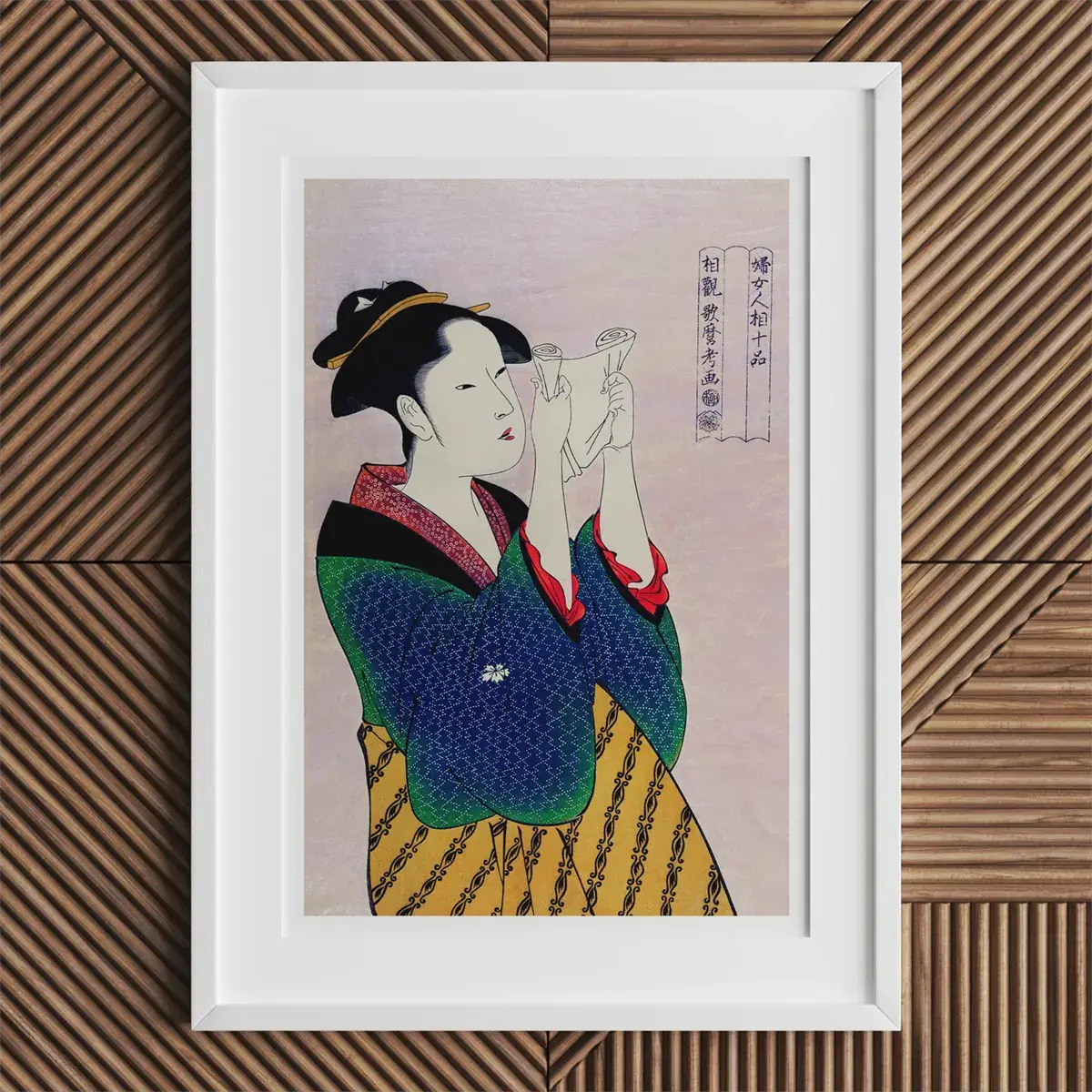

Series like Ten Studies in Female Physiognomy and A Collection of Reigning Beauties reveal his unparalleled skill in rendering both individuality and universal allure, solidifying his dominance within the ukiyo-e tradition.

-

His influence transcended Japan, fueling the fires of Japonisme and profoundly shaping Western art movements such as Impressionism, a testament to the timeless and borderless power of his artistic vision.

Enigmatic Beginnings

Some artists are born into legend; others are swaddled in rumor, and Kitagawa Utamaro belongs irrevocably to the latter. Utamaro entered the world circa 1753—give or take the dust of a year. Although the exact geography of his arrival is lost in a fog of competing stories. Was it Edo, bustling and brazen? Kyoto, draped in tradition? Osaka, alive with mercantile ambition? Or Kawagoe, provincial and steeped in local myths? Historians circle the possibilities like moths drawn to a candle that refuses to burn clean.

His birth name, most plausibly Kitagawa Ichitarō, served as an ephemeral placeholder before other names floated into his life like petals on a summer stream: Yūsuke, Yūki, and finally, Utamaro—the name that would etch itself into the eternal lexicon of ukiyo-e. Some stray accounts even whisper the moniker Kitagawa Nebsuyoshi, adding another layer of silk to the mystery. As for his family roots, they are as mist-veiled as his birthplace. Speculations diverge between a modest teahouse keeper and the esteemed artist Toriyama Sekien, his future mentor. Others suggest samurai blood of humble rank, or simply the anonymous bedrock of the merchant class. In truth, the records are less a biography than an invitation to imagine.

A Childhood of Quiet Genius

What emerges, though, through the murk and mutterings, is the image of a child whose mind already burned with artistic ferocity. Whether framed by lacquered shoji screens or the smoke-tinted rafters of a working-class home, Utamaro's early life pulsed with a growing devotion to line, color, and the alchemy of beauty. That his talents were noticed and nurtured seems certain—parents, teachers, or perhaps mere circumstance recognizing the comet flashing across their quiet domestic sky.

This lacuna in Utamaro’s early biography does more than frustrate historians; it perfumes his story with an alluring, almost predestined anonymity. Like many children of the Edo period’s floating world, his personal history was less important than the shimmer he would cast onto the communal dreamscape. In a society that prized the fleeting over the fixed, where names changed like seasons and identities bent like bamboo, Utamaro's early obscurity was less a flaw and more a signal: he was always meant to be a creature of myth.

Floating World, Fleeting Lives

In the bustling pleasure quarters and smoky kabuki theaters of Edo, permanence was a heresy. Life was a performance, an unfolding pageant of powdered faces, midnight rendezvous, and coins changing hands beneath cherry blossoms. The artists who chronicled this world—the painters, printmakers, poets—moved through it with the same weightless urgency as their subjects. It is little wonder that Utamaro’s life story comes to us piecemeal, stitched from assumptions and half-remembered anecdotes.

The ethos of the ukiyo-e artist was production, not self-mythologization. Fame was a river: you stepped in when you could, but it flowed on without you. Even as Western audiences later fetishized the "enigmatic" Japanese master, reimagining Utamaro as a brooding poet of beauty and sorrow, the original culture he emerged from cared little for preserving the artist’s personal relics. It was the art that mattered—the flicker, the sigh, the velvet trace of a vanished moment pressed into paper and pigment.

Thus, Utamaro remains what he always was: a bright ghost in the great pageant of the Edo period, a mirror held up not to his own face, but to the quicksilver world he so unforgettably captured.

A Formative Apprenticeship

No artistic flame ignites itself. In the great weave of Edo period art, mentorships stitched the invisible fabric where talent became tradition. For Kitagawa Utamaro, this torch was handed down by Toriyama Sekien, an artist whose feet straddled two eras: the refined austerity of the Kano school and the pulsing populism of ukiyo-e. Under Sekien’s seasoned gaze, Utamaro's fingers learned to coax vitality from wood and ink, tracing the delicate muscle memory of generations while daring, even then, to imagine something rawer, brighter, more intimately alive.

Sekien had himself drifted from the heavy silks of aristocratic painting into the freer, looser currents of popular imagery—a shift mirroring the tides of Japan itself. As cities swelled and merchant fortunes bloomed, art unfurled from palatial screens to crowded print shops. Within this shifting landscape, Utamaro’s apprenticeship was not merely a technical education; it was an initiation into a revolution.

Lessons in Wood and Ink

From his earliest days under Sekien’s instruction, Utamaro would have learned the dance of opposites that defines woodblock printmaking: strength and delicacy, patience and improvisation. Every groove carved into the tough cherry wood was a heartbeat, a sentence in the floating world's endless poem. Every pigment mixed was a gamble between vibrancy and subtlety, between the sharpness of reality and the dreamlike hues of memory.

Utamaro would have honed the ancient rituals: the making of the key block, the calibration of kento marks for flawless registration, the layering of colors like whispers building into symphonies. He practiced the art of carving not only surfaces but sensations—the gleam of a silk sleeve, the half-smile before a lover speaks.

Already, the print shops of Edo, fueled by the neon buzz of kabuki theater and the giddy appetite of teahouses, demanded images that could seduce the eye in a glance. Utamaro, still gathering the tools of his future mastery, tested the waters under pseudonyms like Utagawa Toyoaki, shaping kabuki actor portraits and exploring the electric tension between theatrical illusion and human truth.

Merchants and Artisans: A Shifting Japan

The Edo of Utamaro’s youth was a city learning to love itself in reflections: in the taut poses of kabuki stars, in the calligraphy flowing across pleasure-district signboards, in the lacquered surfaces of daily life. The old hierarchies of samurai nobility loosened just enough to allow a new dynasty—the merchant class—to demand, commission, and collect art that spoke to their pleasures and aspirations.

This rising urban patronage birthed a voracious market for ukiyo-e, no longer content with didactic paintings of temples and battles. Instead, the city’s pulse demanded images of its own heartbeat: actors, courtesans, wrestlers, fireworks, lovers glimpsed across moonlit bridges.

Sekien, astute and adaptable, guided Utamaro into this new artistic economy—not as a relic of noble tradition, but as a living, breathing artisan of the floating world. And Utamaro, with eyes like nets cast into the shimmer of daily life, began to gather the material that would later define him: the silences between conversations, the half-turned glance, the infinite novels tucked into a woman’s wrist or smile.

The stage was set. The city was hungry. The apprentice, soon enough, would become a myth.

Understanding Ukiyo-e

To understand Kitagawa Utamaro is to step into the liquid dream that is ukiyo-e—“pictures of the floating world”—a genre less about permanence and more about the tremble of beauty right before it vanishes. Born from the urban fever of the Edo period, ukiyo-e thrived in the alleys, teahouses, and theaters where desire became a daily pilgrimage.

At its heart, ukiyo-e was democratic: it pulled its subjects not from the shrines of old or the battlefields of lore, but from the living pulse of the city. Kabuki actors mid-stride, courtesans glimpsed through a half-open screen, fireworks unraveling against a paper-thin night—these were the heroes and heroines of a Japan newly drunk on itself.

Edo, a city expanding faster than its own myths, became the crucible of this vision, a metropolis eager to see its pleasures mirrored back in bold lines and burning colors. And ukiyo-e, with its commitment to portraying the fleeting and the immediate, became its most eloquent confession.

Stylistic DNA

Visually, ukiyo-e carried the restless DNA of its birth: daring compositions, abrupt croppings that sliced scenes mid-breath, color fields that defied European shading conventions with flat, defiant vividness.

The figures floated, asymmetrical yet balanced by invisible currents; the landscapes were less about realism and more about emotional truth, bending rivers and mountains to fit the dreamscape of memory.

Poetry threaded itself into the images like a lover’s whisper—calligraphy draped over a geisha’s robe, a moonrise annotated by an aching haiku. Ukiyo-e ignored the gravitational pull of traditional perspective, allowing imagination to slide unfettered across the print’s surface.

Lines were not mere outlines—they were living veins, carrying emotional voltage from the woodblock into the viewer’s own nervous system. Color wasn’t decorative; it was alchemical, transforming simple ink and pulp into private, portable heavens.

Art for the People

The true revolution of ukiyo-e was not just aesthetic, but social. Before it, art belonged to temples and warlords; after it, art belonged to the people. The invention of woodblock printing—its carving, inking, and pressing—allowed images once reserved for the elite to flood into the hands of merchants, clerks, artisans, and actors. A man could buy a fragment of beauty for the price of a bowl of noodles.

These prints became the gossip columns, the movie posters, the Instagram reels of Edo’s thrumming life: fashion trends mapped in hairpins and kimono folds, political commentary slipped between portraits of kabuki stars, erotic fantasies etched in secret shunga albums.

As literacy rates climbed and merchant pockets grew heavier, ukiyo-e prints rode the rising tide, morphing into cultural artifacts that reflected not only personal longings but collective identity. They were more than souvenirs of a night out; they were proof that even the most ephemeral moments deserved to be captured, admired, and—ironically—preserved against the very tides of impermanence they celebrated.

In this perfect storm of innovation, appetite, and artistry, Utamaro would later find his natural stage—a world hungry for beauty and complex enough to crave the kind of subtle emotional mapping he alone could master.

The Collaborative Process of Ukiyo-e

In the alchemy of ukiyo-e, no single magician conjured the final spell. A print was not the solitary dream of an artist—it was the whispered conspiracy of many: the designer who sketched the fleeting vision, the carver who etched it into the sinew of wood, the printer who breathed it onto paper, and the publisher who orchestrated the dance and sent it spiraling into the city's bloodstream.

Cherry wood, with its stubborn grain and quiet resilience, served as the sacred medium. It could withstand both the humidity of ink and the relentless pressure of repeated printings, refusing to warp or betray the lines cut into its flesh. Every participant in the process was an artisan, each one threading their distinct heartbeat into the final image.

A single slip of the blade, a tremor of the wrist, and a courtesan's glance might warp into a grotesque parody—or vanish altogether. Precision was not a preference; it was a religion.

Building a Print: Step by Step

The ritual began with the artist's drawing, a web of black ink spun delicately across paper, holding within it the compressed universe of the floating world. This original design, fragile as a moth's wing, was glued face-down onto a woodblock, and there the carver took over, slicing away the spaces between lines to leave the key block: a skeleton of black outlines ready to be inked and brought to life.

This first proof, called the omohan, became the heartbeat of the entire project.

Color demanded even greater devotion. Each hue required its own carved block—sometimes a dozen, sometimes twenty—each aligned with the care of a surgeon using the carved kento marks to prevent even a whisper of misregistration. The colors built themselves up like dreams accreting in layers: the palest pinks first, then the fierce reds, the velvety indigos, the earth-rich greens, until finally the black outlines stitched the vision together.

Each sheet of handmade paper was dampened to just the right thirst, laid atop the inked block, and pressed with a handheld baren, a flat coil of bamboo sheathed in leather. The printer's touch determined everything: too soft, and the image would float away; too hard, and it would sink like a stone into the grain.

Natural Dyes and Alchemical Effects

Until the fevered end of the 19th century, the palette of ukiyo-e printmaking sang almost entirely in the language of the earth: vegetable dyes squeezed from indigo leaves, safflower petals, mulberry bark. These natural pigments shimmered with an intensity born of imperfection—subtle shifts, slight variations, colors that breathed like living things.

Into this earthbound chorus, masters like Kitagawa Utamaro added their own spells. One such was kirazuri, the application of mica powder over freshly printed surfaces to catch light like a net thrown across a river at dusk. A base color was often printed beneath the mica, lending the shimmer depth and warmth, making the background itself vibrate with secret energy.

Another innovation, gauffrage or karazuri, involved pressing patterns into the paper without ink, raising textures invisible to the eye but tactile to the curious fingertip. It was a kind of whisper encoded into the print—a hidden intimacy between artist and beholder.

These embellishments elevated ukiyo-e prints beyond mere popular trinkets. They became portable enchantments, each sheet a carefully layered artifact of collaboration, craft, and collective longing. In the heart of Edo, where life itself was a floating thing, ukiyo-e offered a way to touch the ephemeral and hold it—if only for a moment—in the palm of one's hand.

An Innovative Visual Language

In the crowded constellation of Edo period ukiyo-e, it was Kitagawa Utamaro who taught lines to breathe—to ripple with the pulse beneath a woman’s wrist, to flicker like thought across her downcast eyes. His lines, neither rigid nor careless, moved like silk caught on a shifting breeze: taut, trembling, alive.

Where others etched outlines as if building cages, Utamaro coaxed them into suggestions, invitations, the beginning of secrets rather than their end. Each stroke held its own gravitational field, pulling the viewer inward, erasing the boundary between observer and observed.

His mastery of line elevated the body from anatomy to atmosphere, wrapping the figures in invisible currents of longing, resignation, or sudden delight. Through the simplest curve of a shoulder or the tilt of an eyebrow, entire novels unfolded in silence.

Palettes of Light

Color, for Utamaro, was not garnish—it was a force of nature, equal parts wind and wildfire. His palette sang in high, sweet keys: the blush of sakura pink, the shock of vermilion, the cooling wash of celadon green. Skin remained a luminous, unpainted white, an untouched canvas that glowed with the purity of breath.

Against these colors, he would often scatter the shimmering dust of mica (kirazuri), turning backgrounds into starlit rivers that gave the figures a spectral radiance.

He did not overwhelm the eye with riotous hues; he orchestrated, allowing colors to collide and caress with the precision of a courtship dance. Garments billowed in harmonies of pattern and pigment, and hair glistened like lacquered obsidian under a spring rain.

Each print became a liturgy of light, choreographed with such deftness that the images felt less printed than conjured.

Faces and Figures: The ōkubi-e Revolution

The human face, so often reduced to a symbol in early ukiyo-e, became in Utamaro’s hands a terrain of infinite complexity. His adoption and elevation of the ōkubi-e format—large-headed portraits—marked a seismic shift in the language of Japanese art.

Here, the face no longer floated amid an anonymous context. It became the world.

Utamaro framed his subjects closely, so that the subtle architecture of an eyebrow or the tilt of a mouth carried emotional depth previously reserved for poetry. His women were slender, elongated, their necks swanlike and aching; their eyes long and heavy-lidded, breathing private weather; their lips tiny, painted like the flutter of a red butterfly across porcelain skin.

Through bijin-ga portraits, Utamaro crafted not just idealized beauty, but intimacy, vulnerability, and complexity. Every nuance—the tension of a closed fan, the half-visible sigh of a smile—insisted on the viewer’s complicity. You did not merely look at a Utamaro portrait; you entered it.

Textures Beyond Sight

Beyond color and line, Utamaro layered sensation itself into his prints. He embraced gauffrage (karazuri), the technique of embossing delicate, invisible textures onto paper—impressions that could only be felt, not seen. Hair combs, fabric weaves, the trailing veins of leaves: all rose in gentle relief beneath the fingertips, creating a secret tactile dimension hidden in plain sight.

At the edges of sight and touch, he used mica powder to create surfaces that shifted as you moved, catching lamplight like whispers sliding across a lover’s back.

He also mastered bokashi, the subtle gradation of color that blurred edges and deepened shadows, allowing prints to breathe with twilight softness. Flesh tones moved from moonlit pallor to the faintest flush, garments melted from one hue into another like mist wrapping a riverbank.

Through these layered innovations—visual, tactile, emotional—Utamaro shattered the conventional boundaries of ukiyo-e, transforming it from decorative storytelling into a living, breathing artform capable of holding the entire floating world in a single gaze.

Women at the Forefront

If the floating world had a pulse, it was feminine. In Kitagawa Utamaro’s ukiyo-e, women did not simply appear; they inhabited the page as its elemental force—muses, merchants, mothers, seductresses. They were the drifting stars of Edo’s night sky, each print a small constellation stitched into the darkness.

Courtesans (yūjo) reigned supreme in his compositions: women whose beauty was both occupation and art, icons sculpted by the fever dreams of the merchant elite. Their elaborate hairstyles bloomed like lacquered gardens, and their layered silks unfurled stories with every step. Alongside them stood the geishas, wielding shamisen strings and sly conversation with the precision of a poet threading a needle.

Yet Utamaro's gaze did not fixate solely on glamour. He turned his eye with equal reverence toward the everyday: the housewives balancing domesticity and desire, the shop girls moving through streets thick with the scent of roasted tea and rain-dampened tatami. His art refused to segregate beauty to the stage or the brothel—it shimmered everywhere, in the smallest, most human gestures.

Redefining Beauty

Utamaro’s genius lay not merely in capturing elegance, but in fracturing it, reassembling it into something trembling and true. His bijin-ga were not statues of perfection. They fidgeted, flirted, sulked, daydreamed; their beauty was a shifting tide rather than a static shrine.

With a handful of lines and the barest blush of color, he suggested a woman’s entire emotional atmosphere—the press of anticipation between lips, the exhaustion pooling in eyelids at dawn. His women possessed agency in their allure; they chose to withhold, to reveal, to seduce, to ignore.

Gone was the interchangeable ideal. In its place: individuals. Figures with distinct noses, tilted smiles, and private weather systems simmering just behind the surface. Through this delicate but seismic shift, Utamaro cracked open the conventions of Edo portraiture, allowing for the radical idea that beauty and individuality might be one and the same.

The Mirror of Edo Society

In holding a mirror to women, Utamaro also held a mirror to his world. The Edo period, lush with theatricality yet rigid in class and gender hierarchies, found itself reflected back with all its tensions intact.

His focus on the pleasure quarters—the kabuki stages, the hidden tea rooms—was not mere indulgence. These were the crucibles where fantasy and power collided, where urban aspiration slipped on silk robes and pretended it could outpace the strictures of birth and station.

Through Utamaro’s lens, the floating world shimmered with possibility even as it revealed its fragility. The bijin were not merely objects of desire but avatars of an entire culture’s yearning—for beauty, for pleasure, for some small measure of transcendence amid the confining grids of Edo life.

And though his prints glowed with surface delight, they never lost sight of the deeper ache—the knowledge that all floating worlds, no matter how brightly they burn, are built on impermanence.

Iconic Works and Evolution

Before there was scandal, there was sighing. In his 1788 series Utamakura—“Poem of the Pillow”—Kitagawa Utamaro shattered even the fragile proprieties of ukiyo-e, slipping directly into the charged spaces between bodies, dreams, and skin. These shunga prints were not clumsy provocations; they were orchestrations of breath, pressure, and emotion, rendered with the same velvet precision he brought to more public portraits.

The couples he depicted ranged from innocent to feral, from tender to brutal—each union a different stanza in the floating world’s complicated love song. Far from the formulaic erotica churned out by lesser hands, Utamaro’s Utamakura infused intimacy with narrative, rendering each entanglement less as an act and more as a revelation.

Laced with techniques such as gauffrage (embossing), kirazuri (mica shimmer), and the subtlest bokashi (gradated coloring), Utamakura elevated the erotic into a sensuous, multidimensional art form that dared to explore the unspeakable.

Physiognomies of the Floating World

After mapping the heat of bodies, Utamaro turned his scalpel gaze to the infinitesimal maps etched across women’s faces. In the series Ten Studies in Female Physiognomy and its sibling Ten Classes of Women's Physiognomy, created around 1792–93, he dissected beauty itself—deconstructing smiles, sidelong glances, furrowed brows.

Through these prints, Utamaro inaugurated a new age of bijin-ga: no longer mere mannequins of idealized allure, his subjects trembled with individuality. A woman reading a letter frowns in concentration; another, exhaling smoke, lets fatigue slip into her posture.

Each print in these physiognomy studies felt like a private moment stolen from time, layered with personality and story far beyond surface charm. They served not only as an artistic breakthrough but also as an anthropological one—elevating everyday gestures into monuments of fleeting human truth.

Crowning the Beauties

Utamaro’s ascent continued with A Collection of Reigning Beauties, a crowning achievement that immortalized the celebrated geishas and courtesans of his age. Through careful composition and individualized poise, he moved further away from the abstracted templates of earlier ukiyo-e and into a new terrain of nuanced portraiture.

His portraits in this collection weren’t static representations; they shimmered with internal monologues. Each figure—whether laughing behind a fan, adjusting a hairpin, or simply resting a chin on a delicate hand—radiated self-possession, melancholy, seduction, or playful defiance.

The Three Beauties of the Present Day, produced around 1792–93, distilled this approach into pure essence. In a triangular composition against a backdrop dusted with shimmering mica, Utamaro presented three women—geisha and tea-house maidens—idealized, yes, but with whispering differences in their brows, mouths, and stances. A new world cracked open where beauty spoke not with one voice, but with a symphony of minor keys.

Innovations That Changed Ukiyo-e

It was not merely the beauty of his subjects that secured Utamaro's immortality; it was the way he altered the very grammar of ukiyo-e. His obsessive exploration of ōkubi-e close-ups broke traditional spatial conventions, pulling viewers into a startling proximity with his subjects’ inner lives.

His use of kirazuri turned backgrounds into tactile weather systems, shimmering with moods too subtle to name. His deft handling of gauffrage made garments and accessories tactile metaphors for the layered complexities of identity.

The transition from the raw carnality of Utamakura to the refined emotionality of the physiognomy series mirrored Utamaro’s own evolution—and by extension, that of Edo period art itself. He pushed beyond the spectacle of beauty into the anatomy of feeling, making ukiyo-e not just an archive of appearances but a topography of the soul.

Through technical innovation and radical humanization, Utamaro didn’t just depict the floating world—he remade it in his image, giving it new gravity even as it drifted ever closer to dissolution.

Reflections of the Floating World

The floating world was not simply lived—it was staged. In Kitagawa Utamaro’s ukiyo-e, the brothels, teahouses, and kabuki theaters of Edo became glimmering set pieces for a collective performance where reality and fantasy melted into each other like lacquer warming over coals. Every glance exchanged behind a silk screen, every finger brushing a shamisen string, existed somewhere between invitation and artifice.

Utamaro captured this tension perfectly. His women did not merely inhabit these spaces; they animated them, stitching dreams into the everyday fabric of Edo’s relentless, pulsing life. His prints offered viewers not just portraits but glimpses into an almost religious devotion to beauty—the longing to lose oneself entirely in the ephemeral pleasures of sound, scent, silk, and skin.

At a time when the city itself throbbed with ambition, spectacle, and secret hunger, Utamaro’s images served as the dream journals of a people learning to worship not the eternal, but the deliciously fleeting.

Shadows Beneath the Glitter

Yet beneath all this luster, shadows pooled. Edo period society, for all its appetite for luxury, was rigid and tiered, its caste system a lacquered cage. The courtesans Utamaro celebrated with such tender precision lived lives of extraordinary constraint, their beauty both weapon and prison. Their names might have glittered on the lips of poets and merchants, but their freedom was often no wider than the streets they worked.

Utamaro’s art, though luxuriant on its surface, did not entirely mask these tensions. By chronicling the minute individualities of his subjects—the sigh behind the fan, the furrow before a letter—he exposed the gap between the floating world’s mythology and its flesh-and-bone reality.

In doing so, he offered not an escape from the confines of class and gender, but a bittersweet acknowledgment of them: an art that gilded reality without fully erasing its hard edges.

Beauty and Satire

Nowhere was Utamaro’s deft navigation of these contradictions more apparent than in his forays into shunga, where sexual intimacy became both a source of delight and an opportunity for wry commentary. His erotic prints did not traffic solely in fantasy; they often poked gentle fun at human vulnerability—the awkwardness of a tangled kimono, the ridiculous contortions of lovers drunk on longing.

Even his most sensuous images often carried a grain of satire, a sly reminder that behind every idealized embrace lay the ungainly reality of human flesh and fickle emotion.

Similarly, his portraits of life in the licensed pleasure quarters occasionally edged into quiet critique: gestures stiff with expectation, eyes glazed not with love but with weariness, beauty worn not for pleasure but survival.

In Utamaro’s floating world, dreams shimmered and seduced—but they also revealed the cost of chasing them. His genius was to let both truths coexist without choosing between them: the glitter and the shadow, the sigh and the hunger, the longing and the loss.

Obstacles and Censorship

Even in a floating world built on illusion, there were shoals you dared not touch. For all the shimmering pleasures he captured, Kitagawa Utamaro was not immune to the iron scaffolding of Edo period law. In a society where appearances were tightly policed, certain subjects—samurai pride, historical figures, the fragility of political myths—remained sacred ground, guarded by the ever-watchful hand of censorship.

In 1804, Utamaro misstepped. His crime? Daring to depict Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the sixteenth-century warlord whose memory remained volatile and politically charged. Worse still, Utamaro portrayed Hideyoshi among courtesans—an irreverence unthinkable to the rigid moral order enforced by the Tokugawa shogunate.

In a world where artists trafficked in fantasy, Utamaro’s sin was in pulling history itself into the pleasure districts, in blurring too vividly the line between emperor and everyman, between sanctioned reverence and erotic satire.

It was not beauty that felled him. It was daring to suggest that even the mighty floated on the same transient waters as everyone else.

Chains on the Artist

The punishment arrived with brutal precision. Utamaro was arrested, manacled, and held captive for fifty days—a grim ritual of humiliation designed to reassert invisible hierarchies. The man who had etched grace into wood and shimmer into silk was reduced to a prisoner, his wrists encased in cold iron.

This was not just a personal catastrophe; it was a psychic fracture. Witnesses later spoke of the depression that clouded Utamaro's final years, a dimming of the flame that had once made the floating world blaze so vividly.

His brush, once so attuned to the subtleties of longing and grace, grew heavier, slower. The prints from his later life, though still marked by technical excellence, often lacked the electric immediacy of his earlier works.

Censorship in the Edo period was not merely a matter of ink and permission—it was a violence enacted upon the imagination itself. For Utamaro, the chains did not end with his release. They lingered invisibly, tightening with each cautious line drawn across the face of a world he once dared to dream into being without fear.

Personal Life and Final Years

In the sprawling tapestry of Edo period legends, the personal threads of Kitagawa Utamaro remain loose, fraying at the edges. No diaries. No letters. No records of contracts or grudges or friendships pressed between the pages of history. His life, outside his prints, is less a chronicle than a silhouette—an afterimage blinking in the mind’s eye.

Was he married? Perhaps. Some whisper he was. Did he father children? If so, they left no trail in temple registries or in the cramped margins of city ledgers. His tomb at Senkōji Temple, left untended for long stretches, speaks volumes through its silence: no heirs to burn incense, no descendants to stitch his memory back together.

Instead, Utamaro exists in rumor. Lovers among the courtesans he immortalized. Affairs with models whose faces still glow faintly under layers of pigment and paper. Perhaps some were muses; perhaps others were simply companions for an artist drifting through a world where intimacy was a profession and affection a performance.

History, always hungry for certainties, finds itself gnawing on air when it comes to Utamaro. What remains is the art—the breathing evidence of a life lived in communion with beauty, but not necessarily tethered to the earthbound milestones that define more documented men.

Fading into the Floating World

The twilight years were unkind. Financial troubles, like slow encroaching tides, dragged Utamaro further from the shores of stability. Debt gnawed at the edges of his reputation. Illness, perhaps depression, shadowed his once-fervent creativity.

The arrest in 1804 seemed to break something fundamental—a bright, tensile cord that had tied his soul to the playful, aching world he depicted so vividly. Though he continued to create, the vibrancy dulled, as if the floating world itself had grown heavier, thick with invisible gravity.

On October 31, 1806, Utamaro slipped beneath the surface at the age of fifty-three. His Buddhist posthumous name, Shōen Ryōkō Shinshi, remains, a brittle signpost marking the place where he disappeared into the history he once so vividly shaped.

True to the spirit of the floating world, Utamaro’s ending was less a grand finale than a slow dissolve—a life blurred like wet ink, leaving behind only the luminous fragments we still gather, piece by fragile piece.

Legacy and Global Recognition

The roots that Kitagawa Utamaro planted in the loamy soil of Edo’s floating world grew long, twisted, and startlingly alive. His innovations in ukiyo-e—the close-framed ōkubi-e, the tactile shimmer of kirazuri, the tenderly individualized faces—set fires in the imaginations of artists who followed.

Hokusai and Hiroshige, giants in their own right, drank deeply from the well Utamaro uncovered. His insistence on portraying women as beings of interiority rather than mere ornament reshaped the future of bijin-ga and rewrote the emotional grammar of Japanese visual art.

Beyond the woodblocks, his influence rippled outward, touching the very architecture of fashion, theater, and everyday aesthetics. In the kabuki world, the silhouette of a courtesan, the angle of a comb, the arc of a gaze bore the unmistakable fingerprints of Utamaro’s revolution.

Even in his lifetime, Utamaro was a lodestar for apprentices like Eizan Kikugawa, who inherited the delicate balance of sensuality and subtle narrative that had become Utamaro’s signature.

Crossing Oceans: Japonisme

When Japan’s long-sealed doors creaked open in the nineteenth century, Utamaro’s prints drifted outward like dandelion seeds across oceans, landing with explosive effect in Europe’s parched artistic landscape.

In France, particularly, his influence detonated. Writers like Baudelaire and Goncourt sang his praises; painters like Manet, Monet, and Cassatt drank from his palette of asymmetry, close cropping, and emotional immediacy.

It was through Utamaro’s lens that many Western artists first glimpsed the radical possibility that space could be bent, that beauty could be fragmentary, that emotion could flicker in a single gesture rather than announce itself with grandiosity. His ukiyo-e prints were not simply imported—they were devoured, internalized, reborn into the lifeblood of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.

The movement that became known as Japonisme bore his fingerprints everywhere: in the way Degas framed his ballerinas, in the way Toulouse-Lautrec captured the weary shimmer of Parisian nightlife.

Utamaro had cracked open the Western eye, letting in both elegance and melancholy on a flood tide of borrowed light.

Eternal Allure

Two centuries later, Utamaro’s vision remains undimmed. His prints still hum with the low, electric current of longing—for beauty, for touch, for the fleeting collision of worlds that vanish the moment we name them.

Major institutions—the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the British Museum, the Tokyo National Museum—still prize his works not merely as artifacts, but as living documents of a cultural imagination still urgent and raw. Auction houses watch his surviving prints ascend into the high atmospheres of valuation, testaments to their enduring, almost mythic magnetism.

Yet the true currency of Utamaro’s art is not measured in yen or dollars. It is the sharp, immediate ache his images provoke—the recognition that even now, even centuries later, we are still creatures of the floating world, still chasing reflections across the water’s skin, still dreaming beauty into being even as it slips through our fingers.

In every tilted gaze, every luminous brush of mica across a darkened background, Utamaro offers the same quiet promise: that to love the ephemeral is not to be fooled, but to be fully, painfully alive.