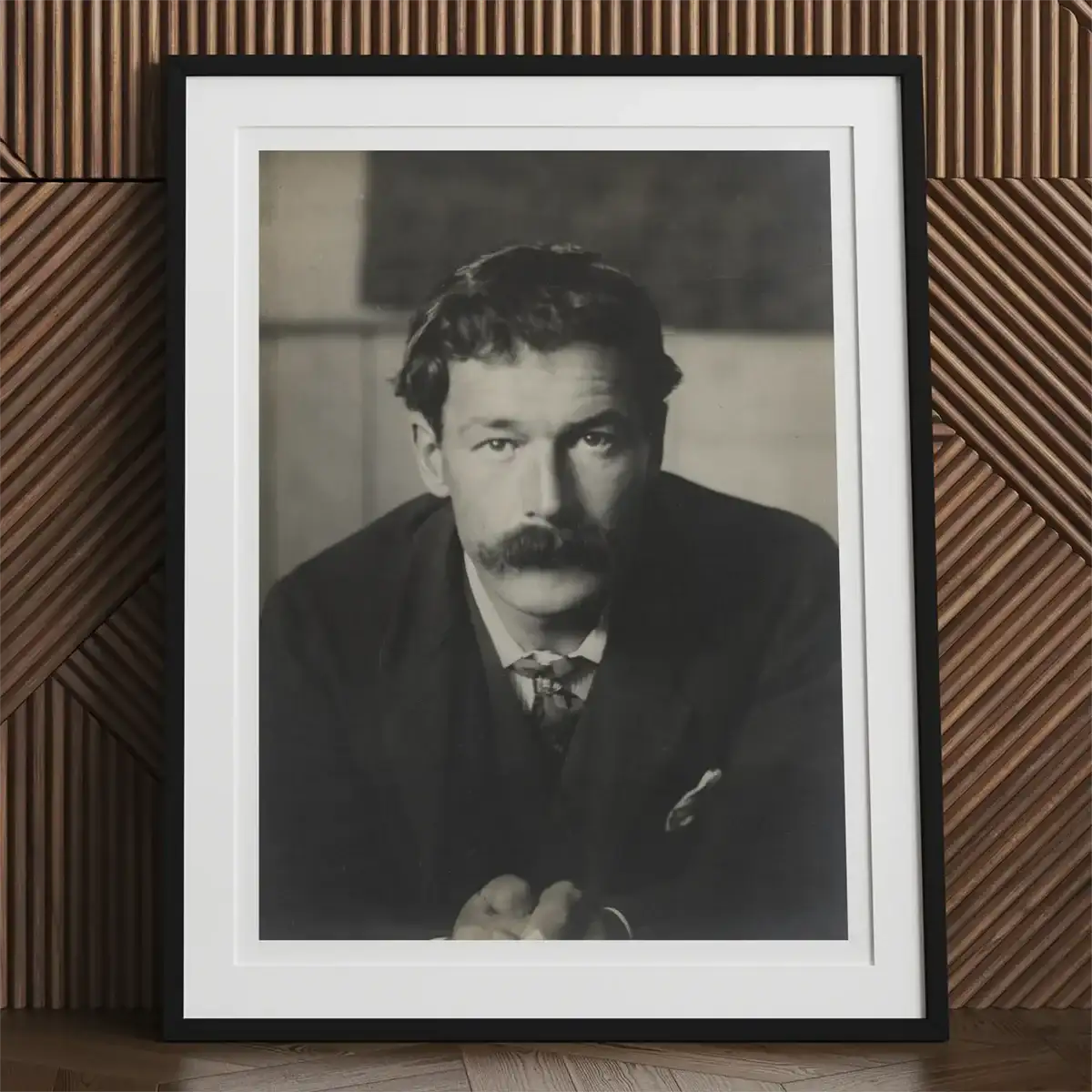

In the golden hour between tide and sky, Henry Scott Tuke watches a young man step into the light. Not staged. Not symbolic. Lit like a secret moment mistaken for innocence. This is where the story begins. Not with scandal or subversion, but with the quiet precision of a gaze that sees what others won’t admit is there.

Henry Scott Tuke didn’t paint ideology. He painted atmosphere thick with unspoken tether. His world wasn’t hidden—it was simply overlooked, sun-bleached into acceptability, drifting just beneath the moral eye-line of empire. To enter his work is to walk the shoreline between beauty and taboo, where the wind carries whispers of devotion, and the body glows.

This isn’t nostalgia. It’s a charged archaeology. The canvas becomes an aperture. And what slips through—salt-streaked, golden, half-silent—are not young men, or brushstrokes, or even truth... it’s the thrill of discovery, possibility and connection.

Key Takeaways

Where empire enforced silence, Henry Scott Tuke staged sunlight—turning young men's bodies into radiant dissent. Transmuting law into lyric, rendering the erotic legible through tide, labor, and myth.

Desire doesn’t declare—it refracts. In Tuke’s work, nothing is stated, but everything glows: intimacy held in the angle of a shoulder, tension suspended in a boat’s tilt, love nested in the geometry of glances that never needed names.

Myth is not escape—it’s a loophole. Classical allusions in his paintings operate like diplomatic immunity: allowing bodies to be naked, admired, worshipped, and mythologized—while still veiling erotic intent in the fog of respectable narrative.

Every canvas is a double exposure. Portrait and protest. Allegory and ache. Under Tuke’s brush, masculinity becomes its own contradiction—resolute yet reclining, heroic yet vulnerable, always on the cusp of undoing itself in beauty.

The queer gaze doesn’t need a manifesto—it needs a horizon. Tuke’s genius lies in his refusal to shout. He paints love like weather: barometric, variable, everywhere. His legacy isn’t an argument. It’s a luminous possibility, still unfolding across the surf.

Sunlit Shores and Secret Desires

There are afternoons that behave like secrets. Not whispered—just unsaid. Henry Scott Tuke knew this. He painted them. Salt-damp bodies along the Cornish coast, young men folded into each other’s shadow and gleam. Not staged. Not coy. Just... held. Arrested in a light that forgets to judge.

His canvases don't moralize. They drift. They stall the machinery of British realism long enough to make space for tenderness. Not softness. Not innocence. Something trickier—proximity without penalty. Look too quickly and it’s tradition: plein air painting, figural study, nautical leisure. But if you slow your gaze—let it dilate—you’ll see what the Royal Academy refused to name: the studied devotion of one boy’s shoulder to another’s spine. A body drawn not to demonstrate musculature, but to admit affection. Tuke’s lens wasn't neutral. It was coded, precise. He didn’t paint youth bathing; he painted the erotic intelligence of sunlight.

August Blue and the Vulnerability of Youth

August Blue doesn’t shimmer. It leans. Toward collapse. Four young men afloat in a Falmouth rowboat, arms slack, backs turned, one nearly slipping into the sea. The horizon doesn’t promise safety. It promises dissipation.

Tuke’s brush edges each form in luminosity, but not celebration. There’s no triumph here. Just the quiet vertigo of adolescent balance—emotional, physical, erotic. He once said he moved to Cornwall “primarily to paint the nude in the open air,” and in August Blue, he does—but the air is heavy, and the nudity not uncomplicated¹.

This isn’t romanticism. It’s a register of exposure. These young men are not allegory, but aperture. The viewer hovers, a breath away from drowning in implication. One wrong movement, and the entire tableau tilts—oar slips, thigh jolts, intimacy exposed. The boat doesn’t just float; it threatens. And Tuke paints that tension in such unblinking blues that you feel yourself blinking too much.

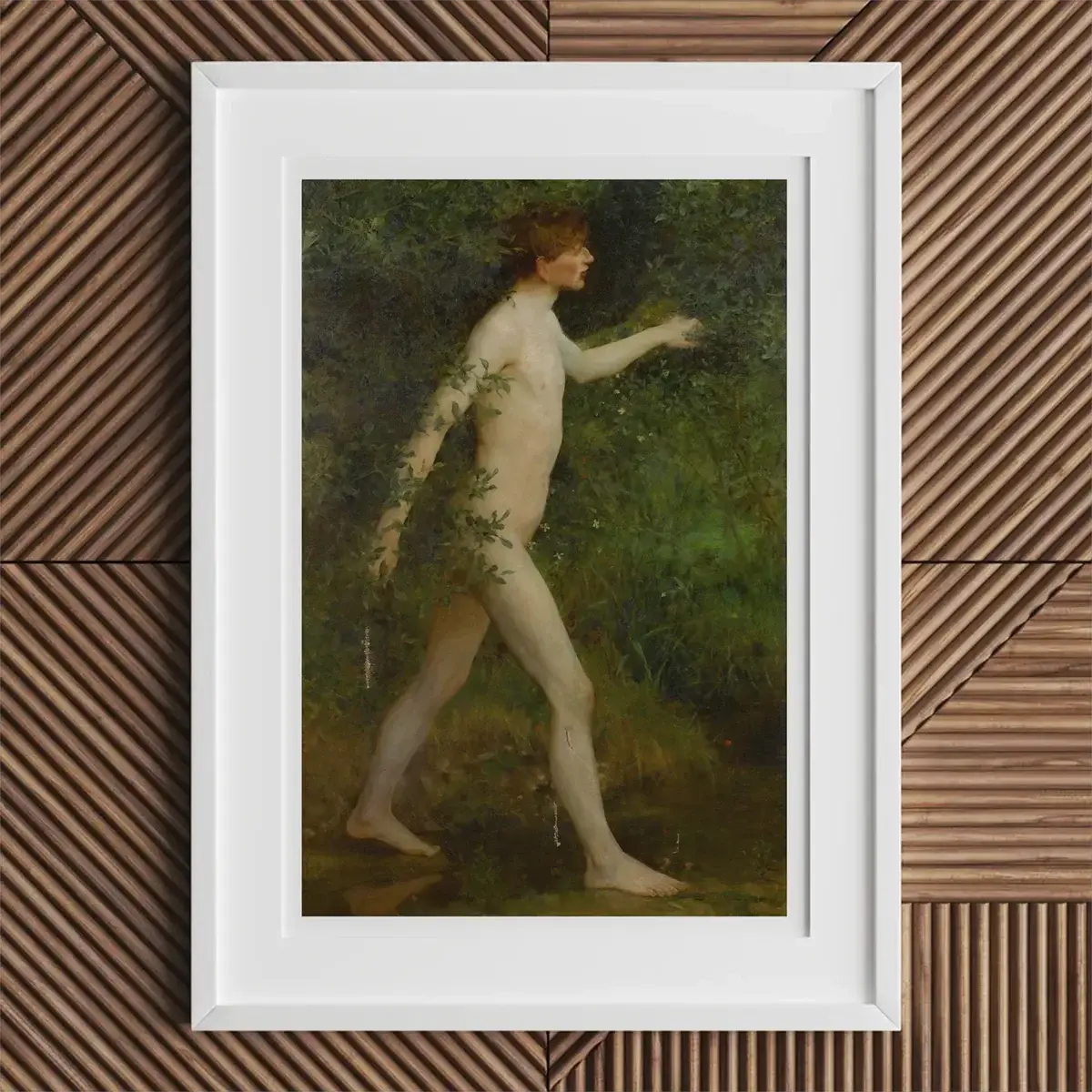

Mythic Subjects and the Queer Gaze

Tuke never needed Olympus. He had enough mischief in Cornwall. Still, when he called a painting Cupid and Sea Nymphs, it wasn’t a reference—it was a disguise. Grapes, wreaths, barefoot wanderers—yes, classical. But filtered through fog, not marble. A myth not borrowed, but blurred.

He understood what mythology allowed: not escape, but camouflage. His young men weren’t demigods; they were adolescents permitted to be unclothed under the cover of Dionysian homage. In Ruby, Gold and Malachite, six figures lounge and play with the careful geometry of desire pretending not to touch. A red jumper wraps like a heartbeat. No action, but plenty of suggestion. And their gaze? Not toward you. Toward each other.

He doesn't eroticize mythology. He mythologizes the erotic. Letting color do what context couldn't. The title names pigment, but the painting names want.

Brotherly Muscle: All Hands to the Pumps! and Noonday Heat

Here, labor is liturgy. In All Hands to the Pumps!, five men wrench at the bilge, salt streaming down the deck and their backs. The British ensign hangs inverted. The ship isn’t sinking, but something is—decorum, perhaps.

These aren’t heroic bodies; they’re necessary ones. Each strain, each rope-pull becomes a choreography of flesh pressed into usefulness. One sailor glances up—not with pride, but exhaustion. Scholar Jo Stanley names it: sensuality in solidarity². They aren’t lovers. They’re limbs made visible. Erotic, not in pose, but in pulse.

Then: silence. Noonday Heat. Two figures on the shore. Half dressed. Naked. Nothing performs here. The water lapping near their feet. And you look. You linger. The painting doesn’t forbid that. It invites you to sit on the warm shore—and stay.

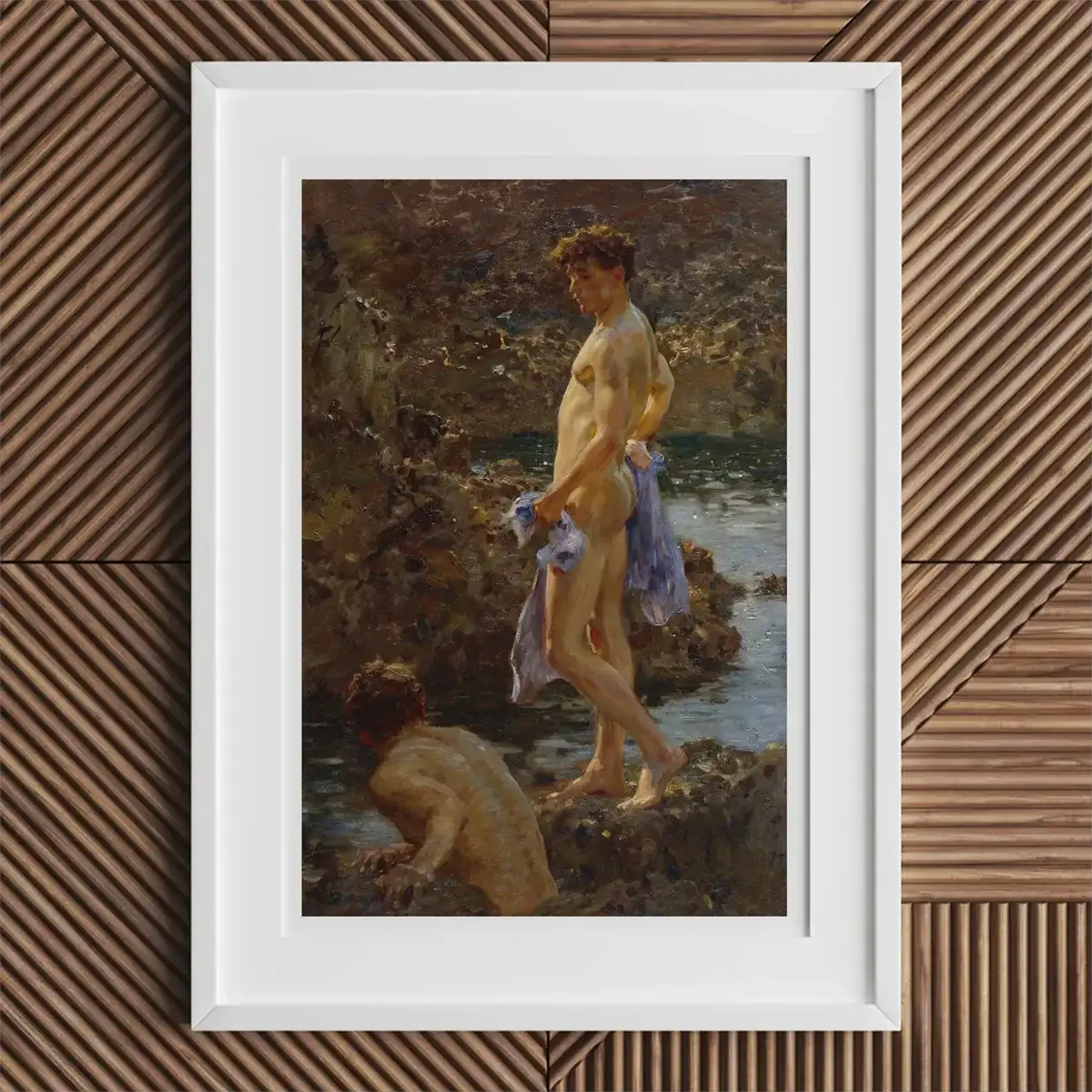

A Bathing Group: Models and Myth

One figure stands. He does not move. He gleams. Nicola Lucciani, imported from Italy, positioned like a lighthouse: vertical, luminous, unignorable. Around him, local fishermen, clothed or nearly, crouch and smirk. One looks up—not in jest, but with a gaze that reorders power.

This is A Bathing Group, and it does not flinch. Tuke stages worship without irony. Apollo isn’t myth here; he’s a hired model, paid by the hour and lit by the sun. The other young men are real too—Falmouth locals, half-laughing, wholly present³.

The composition’s genius lies in its tension: studio and shoreline, ideal and ordinary. But the erotic does not lie with the standing figure alone. It flows between knees and glances, between the sacred and the seaweed. It isn’t about what the viewer sees. It’s about what the young men see in each other. Tuke’s declaration isn’t of beauty—it’s of permission.

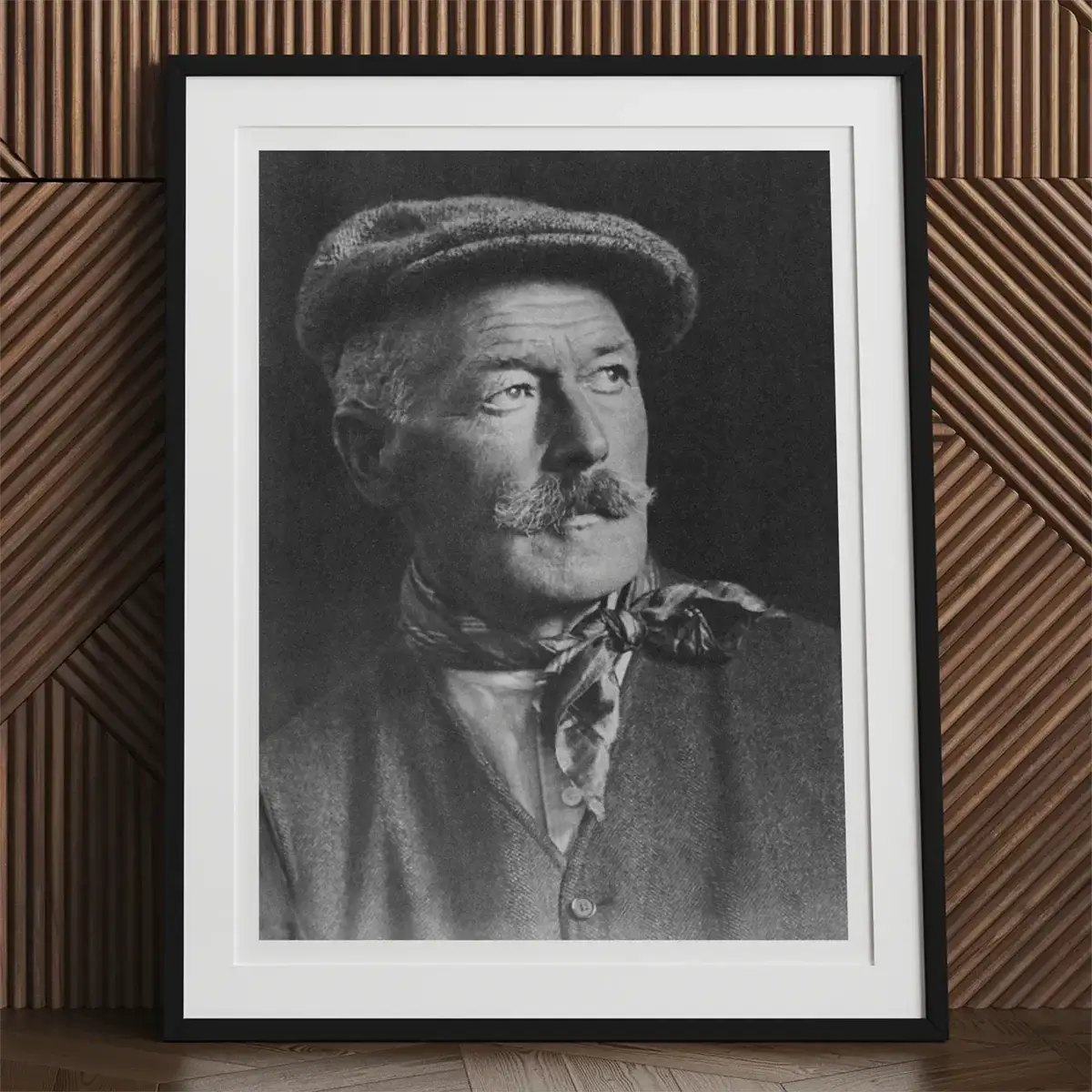

The Critics and the Coastal Male

It ends gently. The Critics is not a defense. It is a memory arranged like a still-life. Five men—no longer boys—sit in soft discord. A towel slips, a hair curls, a hand grazes stone. Nothing happens. Everything breathes.

The title jokes. These aren’t critics. Or maybe they are. Of the tide. Of time. Of each other’s tan lines. The painting doesn’t demand attention; it offers reprieve. After decades of sunlit tension, this is dusk. Not decay—ease.

When hung beside A Bathing Group in the Tate’s Queer British Art exhibition, the effect was elegiac³. Not a repetition, but a reverberation. The erotic here isn’t charged—it’s quieted. Desire aged into knowing. The bodies don’t need to seduce. They remain, and that is enough.

Queer Aesthetics and Social Codes

Tuke lived inside parentheses. In 1885, Parliament outlawed “gross indecency” between men. So he painted young men with limbs like invitations and faces like thresholds—but never crossed the line. He didn’t need to. The Uranian poets did that for him.

His circle included Charles Kains-Jackson and others who exalted Greek-style male love. Their admiration wore robes of purity, but the seams showed. As the Watts Gallery confirms, Tuke’s work was embedded in these homoerotic circuits⁴.

Polite critics called his subjects “healthy.” That’s the lie. The truth is they were desired. Not abstractly. Specifically. Longingly. Carefully. His brush didn’t shout identity; it carved it into the negative space around a hipbone.

Modern scholars call it pederastic. The term fits uneasily. But unease was the point. Tuke didn’t resolve moral contradiction. He painted inside it. That’s what makes the work tremble.

Technique and Composition

Draftsman first, colorist later. Tuke’s precision came from sculpture—form mattered. His young men weren’t outlined; they were modeled. Painted in open air, yes, but assembled with the geometry of classical statuary.

The color hums Mediterranean: cadmium sea, ochre sun, cobalt shadow. But the structure never drowns in pigment. His groupings triangulate, not for symmetry, but for eye-trap. You follow arms to torsos to thighs to nowhere. You wander. You return.

He scaled life-size so you couldn’t avoid proximity. The viewer is always implied—always guilty. Each painting is a stage, and you are seated too close to ignore.

Waves of Influence

For years, he vanished. Not erased—just... filed under “genre.” Then queer scholars looked again. And saw a blueprint.

In 2017, the Tate reunited The Critics and A Bathing Group³. Not nostalgia—recognition. Derek Jarman cited Tuke. David Hockney absorbed him. Young painters saw in those bodies not the past, but permission.

Tuke did not storm barricades. He lit windows. Letting light land on the male form like a hand. Not grabbing. Resting. Staying. Making visible the very thing his century demanded be hidden.

Every sea-soaked shoulder he painted was an argument. Not loud. Not direct. But still political: This, too, is beauty. This, too, deserves frame and wall and gaze.

Reading List

- Art UK. “Henry Scott Tuke: Capturing Light and the Homoerotic Gaze.” Art UK, June 22, 2020.

- Banerjee, Jacqueline. “August Blue by Henry Scott Tuke.” Victorian Web, February 21, 2021.

- Manchester University Press.Naturalism, Labour and Homoerotic Desire: Henry Scott Tuke and the Representation of the Working Male Body. Accessed May 15, 2025.

- Poblete, Nicolás. “Henry Scott Tuke’s Nudes and the Politics of Masculinity.” Canvas: Journal of Art & Culture, September 15, 2016.

- Stanley, Jo. “All Hands Manfully to the Ship’s Gushing Pumps: Henry Tuke and Mrs Peggy.” Gender & the Sea (blog), September 20, 2017.

- Tate Britain.Queer British Art 1861–1967. Exhibition, April 5 – October 1, 2017.

- Watts Gallery – Artists’ Village.Henry Scott Tuke. Press release, May 1, 2021.