The Meiji era (1868–1912) in Japan was nothing short of a cultural metamorphosis — and into this swirling arena stepped Ogata Gekko (1859–1920), an artist who balanced ukiyo-e’s established aesthetics with the era’s dynamic new attitudes. Steam trains thundered along newly laid tracks, gas lamps flickered in foreign-inspired neighborhoods, and a hunger for Western ideas coursed through every stratum of society. Yet amid this embrace of all things modern, ancient art forms still clung to their timeless rhythms.

His life bridged both the old Edo—with its lively entertainment districts and lantern-lit streets—and the emerging Tokyo, defined by top hats, telegraph wires, and fervent calls for reform. The push-and-pull of tradition and progress found expression in Gekko’s versatile masterpieces, from paintings of delicate warblers perched on a single bough to dramatic war prints capturing the Sino-Japanese conflict. Each work bore witness to a society rushing to modernize while never fully relinquishing its past.

Key Takeaways:

- A Mirrored Era of Transformation: Gekko’s life and work epitomize Japan’s Meiji era (1868–1912), a time when centuries-old traditions collided with Western innovations—and produced an art both timeless and breathtakingly modern.

- From Edo’s Lantern Glow to Imperial Patronage: Born Nakagami Masanosuke, Gekko honed his talents painting lanterns and porcelain in Tokyo’s bustling streets, eventually capturing the esteem of Emperor Meiji himself.

- Gekko’s Technical Revolution: His sashiage technique—fusing watercolor-like washes with woodblock printing—redefined how ukiyo-e could emulate the painter’s touch.

- A Vast Palette of Themes: Nature’s quiet grace, the raw immediacy of war, the inner grace of motherhood—Gekko depicted them all, reimagining the floating world for a swiftly modernizing society.

- Bridging East, West, and In-Between: Gekko’s creative lexicon drew from Nihonga, Shijo-style, and even Chinese painting, forging a singular aesthetic that appealed to domestic and international audiences alike.

A Child of Edo: Formative Years and Self-Discovery

Born Nakagami Masanosuke in bustling Edo in 1859, Gekko lost his father—a tradesman—by 1876. The family’s financial reality demanded that the young man work to support himself. He found employment in a lantern shop in the Kyobashi district, where the glow of candlelit designs illuminated his budding interest in artistry. Remarkably, Gekko was largely self-taught, and that independence endowed his art with a certain vividness and freedom of style.

He started by painting on porcelain and adorning the rickshaws that zigzagged through Tokyo’s labyrinth of alleys. An aptitude for designing flyers for entertainment quarters also took hold, immersing him in the vibrant culture of nightly shows and colorful street advertisements. In those early sketches, observers can detect the influence of Kikuchi Yōsai, the painter who laid the groundwork for Gekko’s soon-to-blossom vision.

A Surname with Gravitas

Around 1881, Gekko adopted the surname Ogata, suggested by a descendant of the famed Ogata Kōrin. This choice was not merely cosmetic. Attaching himself to the Ogata lineage granted him a certain prestige in a society that revered ties to influential families. It served as both springboard and mantle: he could soar creatively while reminding the public of his connection to Kōrin’s illustrious tradition.

Backers like Marutani Shinhachi offered financial support and publishing avenues, allowing Gekko to build a professional foundation. Meanwhile, Kawanabe Kyōsai, a celebrated artist in his own right, pushed him toward creating triptychs of current events—a turning point that propelled Gekko into more ambitious undertakings. Steadily, he moved from crafting basic designs to becoming a respected hanshita artist for magazines such as Azuma shinshi (New Azuma Magazine).

Marriages, Mentors, and Many Names

In time, Gekko married Tai Kiku, one of his art students, and also used multiple artistic names—Kagyōrō, Meikyōsai, Kiyū, Rōsai—reflecting his restless and multifaceted spirit. This personal history of reinvention intersected repeatedly with Japan’s national upheavals, granting him an unusual vantage point on everyday life as well as on the sweeping transformations of the Meiji era.

The Evolution of Ukiyo-e: From Courtesans to Warships

Ukiyo-e translates to “pictures of the floating world” and thrived during the Edo period (1603–1868). Traditionally, it captured scenes of sumo wrestlers, courtesans, and tranquil landscapes—imagery deeply tied to the pleasure districts and daily amusements of Edo. But after 1868, the Meiji Restoration introduced railroads, international treaties, and even photography, pushing many Edo-era art forms to the margins.

Rather than vanish, ukiyo-e adapted, featuring Western-style buildings, international exhibitions, and modern marvels like steam-powered vessels. In these transitional works, Ogata Gekko excelled. He seamlessly combined classical forms with contemporary flourishes, merging the elegant lines of past masters with the visual language of a newly industrializing society. A single print might show a geisha’s gown gleaming against the bold geometry of modern architecture, or Mount Fuji nestled amid hints of foreign influence.

The Painter’s Eye in a Printmaker’s World

Most ukiyo-e practitioners worked with crisp outlines and flat color planes. Gekko, drawing on his painting background, leaned toward more brush-like touches. He was determined to capture the fluidity and soft tonal variations typically reserved for ink and watercolor.

This led him to pioneer the sashiage technique alongside Watanabe Seitei, a method that mimicked watercolor washes in the confines of a woodblock print. Gekko also used bold outlines strategically, yet his preferred palette often favored subtle shades. His meticulously rendered kacho-e (bird and flower prints) show how deeply he observed the delicate feathers of a kingfisher or the petals of a blossoming chrysanthemum. Craftsmen unaccustomed to handling these painterly gradations had to adapt, illustrating how Gekko challenged and elevated the entire printing process.

Journeys into Uncharted Subject Matter

The Meiji era was a whirlwind of ideas: classical theater rubbing elbows with modern telegraph lines, traditional garments sharing city streets with western suits. Gekko thrived in depicting this broad tapestry. His artwork scanned everything from placid landscapes and domestic life to mythical lore and the harsh realities of warfare.

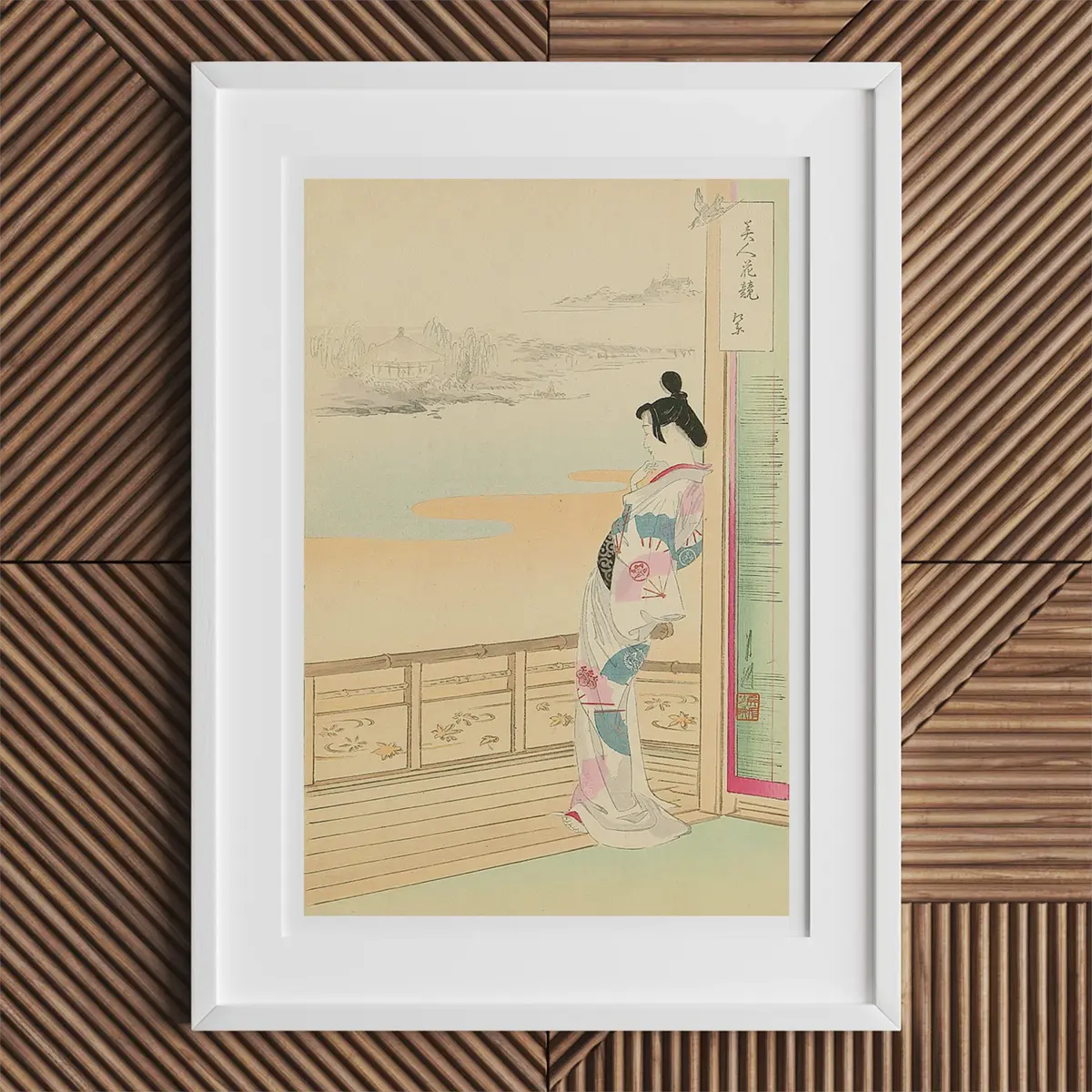

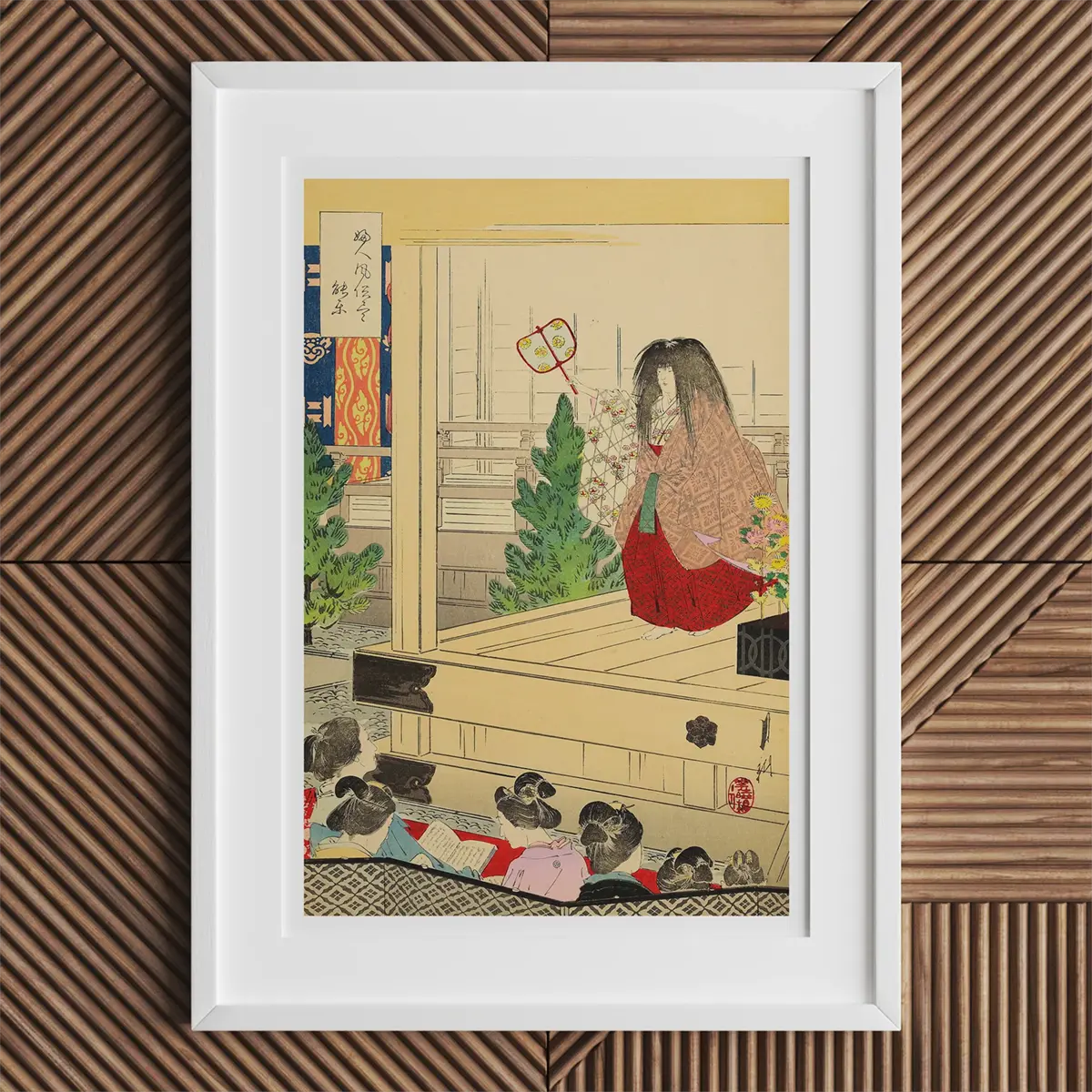

During the Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), he served as a war correspondent, sketching the fervor, chaos, and emotional toll of conflict. His series of war prints captured more than marching regiments and exploding shells; they laid bare the vulnerable human faces behind each military campaign. Elsewhere, Gekko’s bijinga (portraits of beautiful women) often evoked the era’s ideal of wives and mothers, a social archetype the government sought to elevate as part of Japan’s modernization. His genre scenes—mothers tending children, kids at play, craftsmen engaged in daily tasks—became vibrant records of a nation forging a new identity in the crucible of change.

Gekko’s Magnum Opus: Celebrated Series

Though Gekko explored many themes, several series stand out:

Gekko Zuihitsu (1886–1887): Comprising 47 prints and a title page, this suite presents a stunning variety. It lacks one unifying subject, unlike Yoshitoshi’s Hundred Aspects of the Moon, which orbits a single lunar motif. Instead, Zuihitsu finds coherence in Gekko’s distinctive style and the decorative frame around each print.

One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji (Fuji hyakkei): Awarded a Gold Prize at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, this collection celebrates Mount Fuji in the oban yoko-e format. Sometimes Fuji looms large in the foreground; sometimes it’s a discreet silhouette. Scholars have discovered at least two separate series sharing the same title—one without title cartouches, another in portrait orientation (published 1896) bearing title cartouches.

Twelve Months of Ukiyo (Ukiyo Junikagetsu, 1890): Each month’s print symbolizes seasonal or cultural imagery typical of ukiyo-e traditions. The “November” scene, portraying a courtesan perched on a white elephant, highlights Gekko’s flair for mingling the ordinary with the fantastical.

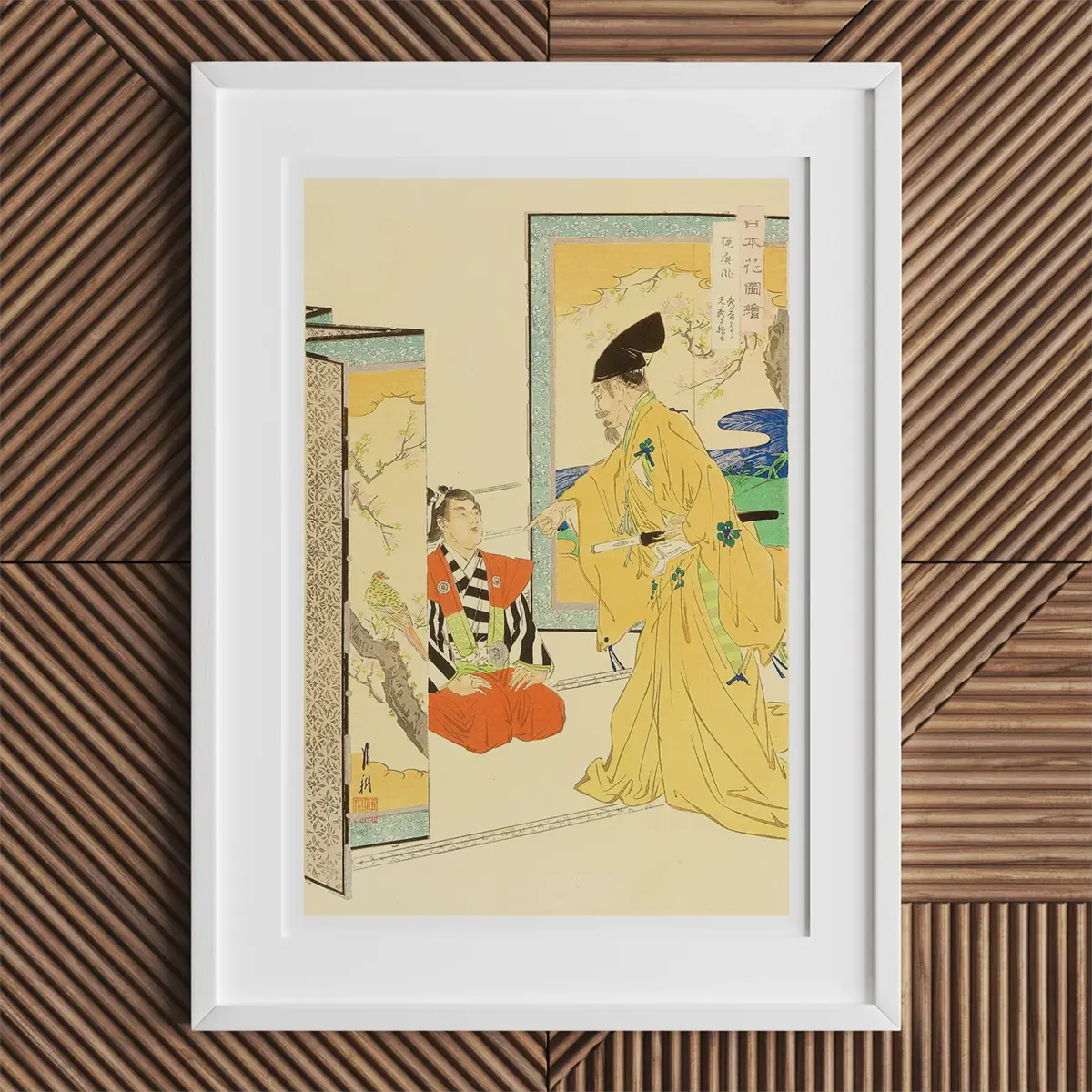

Flowers of Japan (Nihon Hana Zue): Spanning 36 prints published from 1892 onward, it captures notable people, historical milestones, festive pastimes, and even an ancient 800-year-old cherry tree. Multiple publishers and inconsistencies in print quality add an air of mystery to the series’ production story.

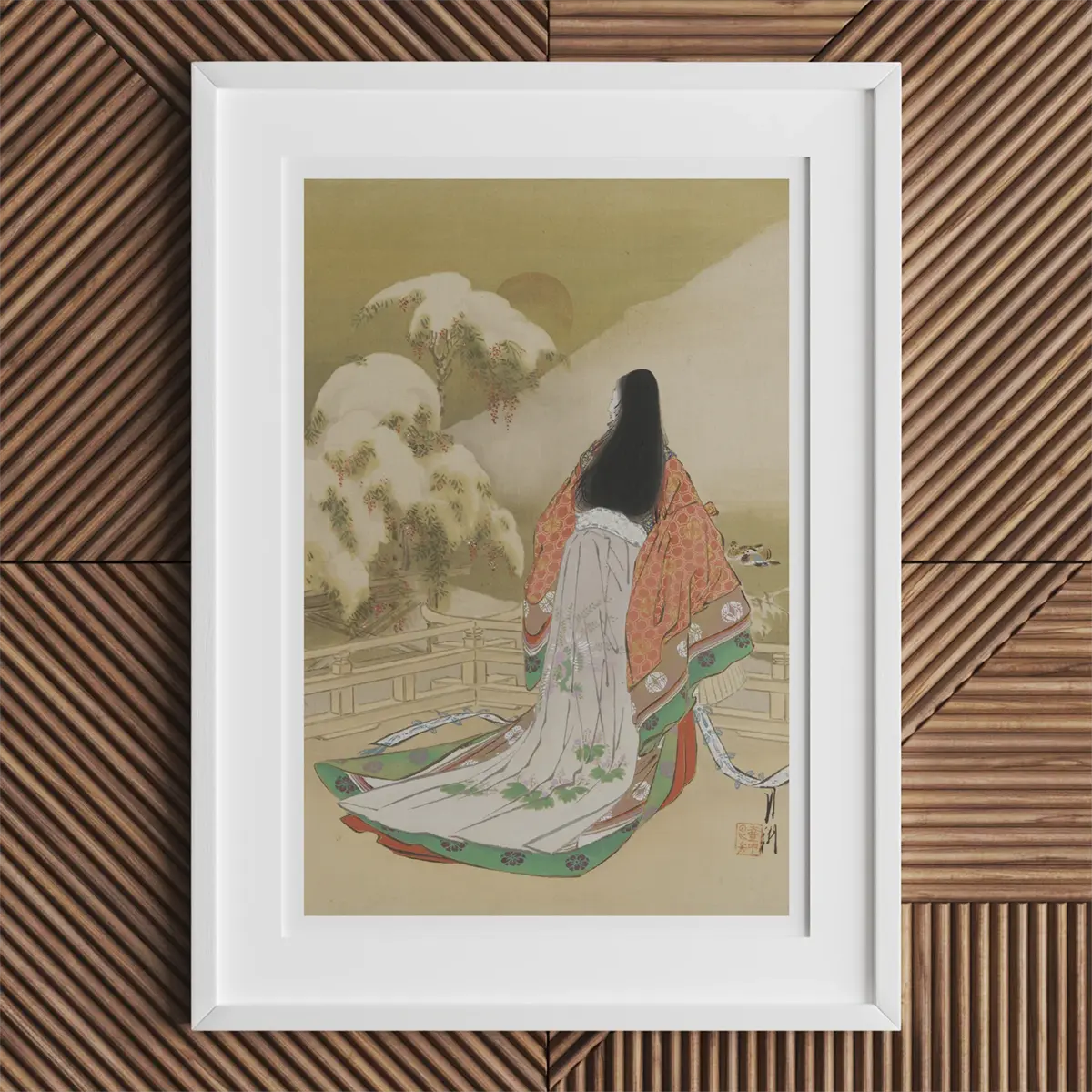

Tale of Genji (Genji Monogatari): By illustrating this cornerstone of Japanese literature, Gekko aligned himself with a revered legacy, unifying classical aristocratic drama with the cutting-edge spirit of Meiji artistry.

Weaving Together Nihonga, Shijo-Style, and More

Although rooted in ukiyo-e, Gekko refused to remain confined to its customary forms. He embraced Nihonga, a Meiji-era movement created to preserve traditional Japanese painting techniques while still selectively adopting Western methods. His experiments with atmospheric perspective and expanded tonal ranges reveal how he harmonized the best of both worlds.

He also absorbed elements from the Shijo-style, known for its expressive brushwork and emphasis on naturalism, particularly visible in his depictions of flora and fauna. Some scholars note a trace of Chinese painting influence as well, evident in his composition and soft washes. In every sense, Gekko embodied Meiji’s broad artistic conversation: forging a fresh, hybrid aesthetic that was distinctly Japanese yet firmly global in its outlook.

Laurels in Life and Fading Footsteps After Death

Gekko’s brilliance did not go unnoticed in his own era. Emperor Meiji personally acquired one of his paintings, while scholars like Ernest Fenellosa and Okakura Kakuzō championed his work both within Japan and abroad. At international gatherings—the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1893) and the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis (1904)—he clinched prizes and expanded his reputation.

But after his death in 1920, his fame ebbed. Photography steadily gained prominence, and newer art styles supplanted much of Meiji’s creative output. Despite this decline, Gekko’s legacy has undergone a resurgence in recent decades. Exhibitions such as “Heroes, Poets, Gods, and Monsters: From Gekkō’s Brush” have reopened the door to his profound technique and historical insight, inviting viewers to rediscover how he navigated tradition and modernity with equal grace.

Contrasting Gekko, Yoshitoshi, and Kunichika

Placing Gekko alongside contemporaries Yoshitoshi and Kunichika Toyohara illuminates their distinct approaches:

- Yoshitoshi (1839–1892) combined Western realism with ukiyo-e, producing bold and frequently unsettling depictions of folklore and historical narratives.

- Kunichika Toyohara (c. 1838–1912) remained loyal to traditional ukiyo-e, focusing on actor portraits and the refined allure of beautiful women.

Interestingly, during their lifetimes, Gekko enjoyed wider acclaim than Yoshitoshi. Only after Gekko’s era did collectors begin favoring Yoshitoshi’s dramatic, sometimes macabre style. By contrast, Gekko’s aesthetic was subtler—more painterly and color-muted—and thematically broader. While Yoshitoshi’s Hundred Aspects of the Moon maintained a unifying element, Gekko’s Zuihitsu ranged freely among myriad subjects, bound by the designer’s unmistakable hand and the frame linking each print.

Lasting Luster of Gekko’s Legacy

As a transitional figure in Japanese art, Ogata Gekko demonstrated that ukiyo-e could flourish well beyond its Edo origins. He showed how modern influences, Western elements, and traditional Japanese painting could all converge in a thrilling new direction. His painterly approach, the sashiage innovation, and his deft use of soft colors widened the potential of the woodblock medium, leaving a creative imprint on future generations.

Just as significantly, his adoption of Nihonga ideals within ukiyo-e mirrored the broader Meiji ambition to forge a national art that respected heritage while welcoming fresh ideas. Though interest in his work declined for a time, the resurgence in collecting and scholarship confirms his enduring power.

Standing as a luminous presence on the horizon of Japanese art history, Ogata Gekko’s flair for merging styles and subjects continues to captivate audiences, ensuring that the glow of his moonlight—to borrow his own poetic motif—shines brightly for years to come.