Flowers have always had their double lives. While one petal turned toward light, the other leaned toward secrecy. And in queer history—criminalized, medicalized and whispered in fear—that doubleness wasn’t aesthetic. It was survival. Where silence was often the only safe language. And flowers bloomed with secrets sewn between their petals. Violet, carnation, lavender—each held emotional voltage that crossed centuries of prejudice and love in the shadows.

Picture the stillness of an Edwardian parlor: the way lamplight glints off a green carnation pinned with surgical precision to a Oscar Wilde's lapel—a badge not of fashion, but fraternity. Or imagine the hush of a boarding school dormitory, a girl pressing violets between the aching verses of Sappho, preserving her longing as if it were a sacred relic. Each a coded script authored by those denied the dignity of love in the open. And yet they remained unwilling to go unloved or unseen.

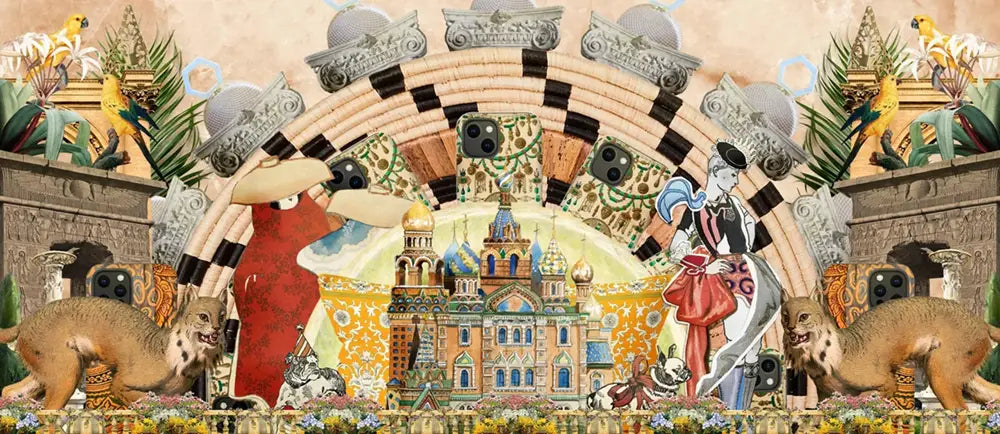

Floriography, the 19th-century art of flower symbolism, gave queer lives a palette when the canvas of culture offered only erasure. And so a secret garden grew. Beneath the noses of propriety, within bouquets crafted with clandestine care, messages passed from hand to trembling hand. To decode them now is to unlock a parallel history—a lush, unspoken lexicon of love, longing, protest, and pride. One that's carried on into the here and now.

his isn't a tale of polite posies of Victorian dinner parties. Or the gaudy extravagance of wedding centerpieces. These are all insurgent blossoms. Rebellious. Frail as breath but defiant as thunder. In a world policed by conformity, a single bloom can whisper, beckon, signal or scream. Invisible to most, electric to the few who understand. Because these aren't just flowers. They're lifelines.

Key Takeaways

- Ancestral schoes: Trace how flowers became more than ornamental—from the olive groves of ancient Lesbos to lavender-sashed marches post-Stonewall, these coded blooms thread a lineage of queer resistance.

- Danger and defiance: Green carnations weren’t just Wildean whimsy. Violets weren’t just tender. Lavender wasn’t just soft. Each bore risk. Each masked a dare. Each is a chapter in the queer canon of subversive survival.

- Reclamation and rebirth: Watch language turn inside out—how pansy went from slur to standard-bearer, how lavender menace became lavender might, how silence turned into a war cry dressed in florals.

- Artistic testaments: From Georgia O’Keeffe’s pulsing lilies to Oscar Wilde’s sardonic lapels, from underground Japanese cinema to lesbian pulp fiction, queer flowers sprawl across the archive—flagrant, fragrant, unforgettable.

- Ongoing evolution: As identities diversify, so too do their symbols. Orchids for intersex identity. Trilliums for bisexuality. Bouquets as intersectional manifestos—still unfurling, still unfinished.

Green Carnation: Oscar Wilde’s Dandy Declaration

Wilde’s Bold Gesture

The year was 1892. The theatre glowed with expectation. And into its velvet hush stepped Oscar Wilde, trailing a bouquet of scandal dressed in style. For the premiere of Lady Windermere’s Fan, he curated a scene not merely theatrical, but mythic. On his lapel: a green carnation, dyed by hand. Several of his admirers wore them, too. Petals tinged with a color no garden could grow. When asked why, Wilde’s response dripped with mischief: “Nothing whatever, but that is just what nobody will guess.”

Of course, it meant everything.

Artificial, flamboyant, and deliberately out of season, the green carnation became an instant symbol. Not just of Wilde’s aesthetic rebellion, but of coded queerness. In a world that prized cisgendered, patriarchal, binary concepts of nature and ‘normalcy,’ here was a flower that paraded its unnaturalness with pride. Resplendent in its subversion. Ostentatious and surreptitious in ways that mirror Wilde's signature wit.

‘Unnatural’ Mockery

The green carnation’s very artifice mirrored society’s own accusations. Homosexuality, labeled unnatural, found in the dyed bloom its flamboyant twin. The flower’s unnatural hue wasn’t just decorative. It was Wilde’s aesthetic retort. As a leading figure in the Aesthetic Movement, which exulted in beauty, stylization, and deliberate artifice, Wilde wrapped defiance in elegance.

Scholars now read the green carnation as a calculated affront. A botanical masquerade mocking Victorian morality. For Wilde’s circle, queerness was not hidden beneath surfaces. It was the surface, glinting with irony. The carnation, though absurd to the unknowing eye, became a linchpin of rebellion cloaked in chic.

Cultural Footprints

By 1894, The Green Carnation, a satirical novel by Robert Hichens, crystallized the flower’s infamy, lampooning Wilde’s clique and feeding into the public scandal that loomed. The carnation’s symbolism sharpened—from mischievous accessory to damning signpost. Its visibility cast shadows on Wilde’s reputation, ultimately adding heat to the inferno that consumed him.

And still, it lingered. In the 1960 biography film The Trials of Oscar Wilde, retitled The Green Carnation in some releases, the bloom reappeared as symbol and cipher. Rupert Everett wore it again in a cinematic rendering of An Ideal Husband, each petal haunted by history.

Though it began as a polished jest among sophisticates, the green carnation became a precarious emblem, marking devotees with both subtle recognition and genuine risk.

Lavender: A Hue of Gay History, Resistance, and Pride

Early Associations

Long before lavender crowned graduation stoles or bloomed across rainbow flags, it hovered at the periphery of coded language—a color tinged with insinuation. In the 1930s, “lavender lads” became shorthand for gay men, a phrase both floral and slanderous, a perfumed barb from a society trained to sniff out deviation. The insinuation was effeminacy. The consequence was exclusion.

And yet, the roots reach deeper. In 1926, poet Carl Sandburg wrote of Abraham Lincoln possessing “a streak of lavender, and spots soft as May violets,” a delicate phrasing some have interpreted as hinting at queerness. Though historians remain divided, the mere possibility reflects lavender’s longstanding association with the unspeakable, the speculative, the stigmatized.

By the 1950s, the Lavender Scare brought its association to full bureaucratic bloom. Alongside the better-known Red Scare, this purging campaign equated homosexuality with national disloyalty. Government workers lost jobs. Reputations evaporated. Lavender was no longer subtext. It was accusation.

From Persecution to Empowerment

Lavender, ever adaptable, turned in the wake of Stonewall. With queer activists refusing to cede meaning to their oppressors. During a “gay power” march in 1969, protestors donned lavender sashes and armbands, transforming the color into a unifying banner. What had once been used to mark and malign now became fabric threaded with fury and self-determination.

Around the same time, second-wave feminist Betty Friedan labeled lesbian presence in the women’s movement a “lavender menace.” Rather than shrink, lesbian activists embraced the phrase, staging a protest at the 1970 Second Congress to Unite Women. They wore t-shirts printed with “Lavender Menace” printed on them. Turning the slur into a spotlight. Lavender had become insurgent. Soft in hue, sharp in resolve.

Broader Symbolism

Today, lavender thrives not just in gardens, but in ritual, literature, and law. Lavender Graduations honor LGBTQ+ students. Legal minds gather at the Lavender Law Conference. Its symbolism is woven into every layer of queer cultural life.

Oscar Wilde referenced “purple hours” as euphemisms for love. Alice Walker’s The Color Purple gave literary breath to Black queer tenderness. Leslie Feinberg’s Stone Butch Blues bathed lavender in the glow of trans defiance.

Once a coded whisper, now a thunderous bloom, lavender has moved from the periphery to the heart of queer identity. Proof that even the faintest hues can come to paint revolutions.

Lilies: A Bloom of Beauty, Purity, and Sapphic Interpretations

The Japanese Yuri Connection

In Japan, the white lily is more than a symbol. It's a language. A bloom that speaks not only of grace and purity, but of longing blooming in secret. The word “Yuri,” meaning lily, gave rise to an entire genre. Romantic and emotional narratives between women, rendered in manga and anime, steeped in both the sensual and the sacred.

These aren’t just petals on a page. They’re metaphors, soft but unflinching, for relationships that ripple beneath surface norms. Sometimes delicate, sometimes daring, always steeped in the tension between silence and expression, the yuri lily became a proxy for sapphic desire in a society where overt declarations carried weighty risk.

The O'Keeffe Question

Across the Pacific, lilies—particularly calla lilies—blossomed anew under the gaze of painter Georgia O’Keeffe. Her florals, oversized and intimate, invited speculation. Erotic, some said. Lesbian, others whispered. O’Keeffe resisted categorization, yet the sensuality in her work remains undeniable.

Art historians and queer viewers alike have found a quiet audacity in her petals. Suggestive forms that resist containment. Whether read as blooming genitals or pure abstractions, her lilies continue to inspire debate.

Orchids: On an Intersex Adventure

Etymological Roots

The orchid is a flower of contradictions. Elegant, intricate, and named for testicles. The word derives from the Greek orchis, referencing the shape of the plant’s underground tubers. This etymological quirk extends far beyond botany: in medical parlance, “orchidectomy” refers to the surgical removal of testicles. And here, the orchid’s subterranean symmetry meets the lived experience of intersex people.

For many intersex people, medical intervention is not a choice but an imposition. Performed in childhood, framed as “correction.” The orchid, with its deceptive grace and anatomical undertones, becomes a potent emblem. It speaks to the fraught relationship between the natural and the normalized, the bodily and the binary.

Symbol and Solidarity

This symbolism is no abstraction. Several intersex advocacy groups now feature orchids in their visual identities. The flower’s legacy was further cemented by Orchids: My Intersex Adventure, a raw and revelatory documentary by Phoebe Hart. Through the bloom, the film explores autonomy, bodily integrity, and the cost of invisibility.

Vibrant yet misunderstood, the orchid mirrors intersex identity itself. Multifaceted, medically misread, and in urgent need of visibility and respect.

Pansies: Derogatory Slur to Cultivated Symbol of Gay Pride

From Insult to Icon

Delicate. Downtrodden. Derided. The pansy was never just a flower. It was a weapon. From the French pensée (“thought”), it conjures fragility, introspection, softness. No surprise, then, that the patriarchy twisted into a slur. In the early 20th century, “pansy,” along with “buttercup” and “daisy,” was lobbed like a stone at effeminate men, those who dared to deviate from the confines of prescribed masculinity.

Ironically, it was precisely the pansy’s ethereal beauty—bowed head, velvet face—that made it both target and totem. It became shorthand for queerness, a floral punchline with a bruised kind of brilliance. It was also reclaimed by queer folks many times over.

The Pansy Craze

Queerness is nothing if not reclamation. In the 1920s and 1930s, the “Pansy Craze” swept underground clubs during Prohibition. Queer performers—many drag queens, many defiantly out—adopted the term with flair. “Pansy performers” sang, danced, and strutted in full view, twisting the insult into a crown.

Mainstream society looked on with a mixture of scandal and fascination at these blooming pansies—all cheeky, subversive, loud and proud.

Reclamation in Action

Reclamation continues today. Artist Paul Harfleet’s ongoing Pansy Project plants actual pansies at sites of homophobic and transphobic attacks. Tiny floral monuments marking places of trauma with beauty, memory and resolve.

The pansy’s original symbolic meaning—remembrance—deepens further and further. Echoing through queer resilience. To be worn, planted, painted, and sung. Full circle and always in bloom.

Roses: Thorned Emblem of Love, Loss, and Transgender Visibility

A Rose With Many Names

The rose has always been loaded. Love. Death. Devotion. Deceit. Its petals are soft but its thorns are sharpened history.

In LGBTQ+ iconography, the rose’s meaning unfurls within the transgender community, where it symbolizes not just beauty, but survival. “Give us our roses while we’re still here,” said trans artist B. Parker, reframing the floral idiom as a plea for visibility and care. Not as memorials for the fallen, but recognition for the living.

On Transgender Day of Remembrance, roses are offered in vigil, honoring lives lost to violence while acknowledging those still fighting to be seen. It is both offering and uprising.

While in Japan, the word bara (rose) was once used as a pejorative for gay men—loaded with stigma. But in time, that too was reclaimed. Magazines like Barazoku (“rose tribe”) embraced the word, folding it back into queer culture, refusing to let insult go unbloomed.

And at many Pride parades, roses appear in tie-dyed swirls—rainbow-hued blossoms that merge classic symbolism with queer color theory. Lavender roses add another layer: a collision of old-world romance with defiant new-world queerness.

A Cinematic Edge

Then there’s Funeral Parade of Roses (1969), Toshio Matsumoto’s avant-garde masterpiece set in Tokyo’s underground gay and transgender scene. The rose here isn’t delicate. It’s dangerous. Blood-tinged. Psychedelic. Erotic. The film fractures identity and narrative, casting the rose as a prism through which queerness pulses, performs, bleeds.

In queer hands, the rose transforms again and again. A bouquet of meanings. A blade in disguise. A bloom that never dies. Only multiplying. Each petal a name, a fight, a love.

Trillium: A Botanical Nod to Bisexuality

Defining Features

Three petals. Three sepals. Three leaves. The trillium wears its geometry like a sigil. Each triad a quiet mirror to bisexuality. Found in forest understories, the flower holds a sacred symmetry. Neither flamboyant nor anonymous, just quietly exact.

It was artist and activist Michael Page who saw in its structure a metaphor too precise to ignore. Botanists had long referred to the trillium as bisexual, describing its reproductive traits. Page took that term and turned it into a symbol. Not just biological. Political.

When Page designed the bisexual pride flag in 1998, he imagined a visual landscape where the trillium could bloom as avatar.

Flying the Flag

By 2001, the white trillium appeared on the Mexican bisexual pride flag, adding botanical flourish to a growing international movement. It gave the flower a new context. No longer just a forest bloom, but a flag-bearing envoy in the wider LGBTQ+ field.

A trifecta of visibility, complexity, and symmetry—the trillium stands, quietly but clearly, for the truth that attraction doesn’t live in binaries. It blossoms, instead, in threes.

Violets: Sappho’s Verse to Modern Emblem of Lesbian Love

Ancient Resonance

Small, unassuming, and low to the ground—violets might be easily overlooked. But they hold within them one of the most enduring signals of lesbian love, stretching back to 7th-century BCE.

On the island of Lesbos, the poet Sappho wrote verses so charged with longing they still shudder across time. She described women crowned with garlands of violets, the purple bloom threaded through hair and metaphor alike.

This wasn’t floral garnish. It was emotional architecture. For Sappho, violets were adornment and declaration. A lush articulation of intimacy between women in a world with no name for such things.

Early 1900s Revival

Centuries later, the violet bloomed again in the lives of women seeking language for their desire. And lineage.

In the early 20th century, many lesbians quietly wore violets pinned to their clothing, a gesture subtle enough to slip under suspicion yet bold enough to be legible to those in the know. A bloom, a code, a shared axis of identity.

This was not trend but tribute. An invocation of Sappho’s defiant spirit, the violet connected modern queer women to their ancient foremother.

A Theatrical Bloom

The flower reached a flashpoint in 1926, when Édouard Bourdet’s play The Captive (La Prisonnière) portrayed a lesbian relationship. Where the characters exchanged bouquets of violets as an act of love rendered in petals rather than dialogue.

In France, the audience responded with solidarity, donning violets on their lapels. But across the Atlantic, in New York, the reaction was swift and punitive.

The play was banned. Sales of violets plummeted. Florists feared the association. The flower was marked... and more potent than ever.

Creative Echoes

Violets continued to haunt queer creative expression. Tennessee Williams’s Suddenly Last Summer featured the character Mrs. Violet Venable, her name a deliberate nod. Renée Vivien, called the “Muse of Violets,” laced her sapphic poetry with their scent. In the 1996 film Bound, a violet tattoo served as unmistakable signal: lesbian identity, inked and unhidden.

From corsage to controversy, from whispered code to cinematic flash, the violet has remained rooted in defiance and desire. It is both fragile and unshakable. A flower that has never needed to shout, because it always knew how to speak.

The Enduring Legacy: Flowers as Timeless Symbols of LGBTQ+ Culture

Flowers have always been more than decoration. For queer communities across centuries, they became lifelines. In the vacuum where rights should have been, blooms carried messages too dangerous to speak aloud.

A green carnation wasn’t just a flourish. It was a dare. A pansy was more than an insult. It became an anthem. Even when the world refused to listen, flowers spoke.

Reclamation is the pulse behind every petal. What was once used to wound—“pansy,” “lavender menace,” “bara”—now bursts into the world as pride, protest, and poetry.

Each flower marks a chapter in the ongoing bloom of queer culture. Not frozen in time, but alive—expanding. What once had to hide now crowns stages, courtrooms, and campuses.

Yet the memory remains. Every bloom carries history in its roots. The cost of visibility. The beauty of resistance. The tender ache of those who came before.

A flower, after all, is temporal. But what it symbolizes is eternal. That flicker of recognition, that thrill of defiance, that ache for belonging

In every lily, carnation, violet, or rose lies the quiet insistence: I'm still here. In every garden where a child tucks a flower behind their ear, in every bouquet slipped to a lover across barriers of silence, the legacy persists.

Love, like a bloom, will always find its light.