For centuries, Western audiences devoured Orientalist art for its lush depictions of distant lands. An atmospheric thrum carried in canvas: minarets glowing in sun-flared gold, bazaars stitched with dust and desire, desert skies drawn taut like silken sheets. This is the painted Orient as Western artists imagined it—gilded, distant, intoxicating—and yet, for all its exotic performance, something more intimate stirs beneath the pigment. Something forbidden. Tender. Sensuous.

Beneath the jeweled surface of Orientalist art lie entanglements of conquest, sexuality, and the deeply coded transmission of queer longing. A charged erotic stillness. These paintings do not merely offer “views”; they become mirrors of what could not be openly named. A young man kneeling, another bathing, a hand brushing shoulder or hip—these are signals, not scenery.

These are not just panoramas of camel trails and mosque domes. These are charged fictions—desire disguised in ethnographic costume. The homoerotic gaze, hidden in folds of fabric and shimmered oil, pulses quietly beneath.

Understanding these cues matters. Because to read Orientalist painting only as colonial fantasy is to miss the silent revolutions happening in its shadows. These were sites of subversion—of erotic imagination pushing against empire’s own puritanical skin.

They show us how queer desire has always found its way through the cracks of empire’s veneer. And how the male gaze—when turned toward other men—becomes both a weapon and a whisper. A document of power, yes. But also, sometimes, a sanctuary of unspoken want.

Key Takeaways

-

Echoes of Desire: Many 19th-century Orientalist paintings of the Middle East and North Africa carry veiled, often overlooked homoerotic elements—acts of same-sex attraction coded in posture, glance, and gesture.

-

Power and Gaze: The homosexual male gaze within Orientalist art intertwines with imperialist structures, exposing how colonial dominance and sexual projection coexisted in brushstroke and backdrop.

-

Parallel Traditions: While Western artists cloaked homoerotic desire in ambiguity, Persian miniatures and Ottoman manuscripts offered more explicit, nuanced representations of same-sex intimacy.

-

Queering the Canon: Artists like Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann challenged heterosexual norms by reimagining Orientalist tropes through a queer female gaze, offering alternative readings of both subject and context.

-

Enduring Resonance: Scholars such as Edward Said and Joseph Massad compel us to reexamine Orientalist art through a critical, queer postcolonial lens—insisting that we see not only what was painted, but why, and for whom.

A Journey Beyond the Surface

Paris, 1870s. The city pulses with ink—travelogues, journals, telegrams inked with heat from faraway ports. Cairo. Constantinople. Algiers. Their names fall like perfume in literary salons, thick with tobacco and hunger. What returns from these places is not just geography, but glimmer: the boy who danced at dusk, the servant whose hands trembled pouring tea, the curve of a stranger’s throat glimpsed through a muslin veil.

These fragments—half-fantasy, half-report—became the scaffolding of a Western mythos. Artists brought back not just sketches, but souvenirs of longing, made palatable by distance and disguise. In canvases drenched with ochre and shadow, Orientalist art emerged as a quiet stage for erotic projection, its intimacy camouflaged by cultural masquerade.

And so, behind every sunlit minaret, a whisper. Behind every market stall, a pulse. This is not simply documentation—it is dreamwork. And from this embroidered veil of myth and yearning, the story of homoerotic Orientalism begins to unfurl.

Veils and Vistas: Setting the Scene of Orientalism

Orientalism didn’t emerge from a void—it arrived draped in velvet and violence. By the 19th century, European powers had turned empire into spectacle. Algeria bled under French boots, Egypt bent beneath British rule, and in the salons of London and Paris, the “Orient” became less a geography than a fever dream. Artists answered the public’s appetite for the exotic by conjuring luminous bazaars, cascading veils, and desert reveries. But beneath every canvas: conquest.

Edward Said would later name this mechanism: a visual and ideological theater in which the East existed only as Europe’s painted foil. Orientalist art, no matter how detailed, never truly depicted Algeria or Damascus—it reflected the West’s hunger to dominate what it desired.

Still, two currents moved within this aesthetic tide. Some artists—Delacroix among them—sought truth through travel, sketching men and minarets as they found them. Others remained in their studios, conjuring fantasy geographies from memory, books, and longing.

Regardless of method, both streams swelled into a visual language charged with power, seduction, and myth. And stitched into this imperial tapestry was something even more elusive: Homoerotic desire. A hand too softly placed. A boy too luminously lit. Within the folds of turbans and the shadows of courtyards, desire flickered.

These artists didn’t need to be queer themselves. The system they painted within made room—sometimes unwittingly—for the homosexual male gaze to nestle inside the heterosexual one. Colonialism, after all, didn’t just conquer land. It re-scripted bodies, rearranged desire, and recast intimacy as a foreign thing to be framed, consumed, and—perhaps—secretly adored.

This is where the veils lift. This is where the vistas widen. And here, homoeroticism begins to shimmer behind the scrim of empire.

Gaze Expanded: From Heterosexual Precedent to Homosexual Glimpse

John Berger once wrote that men look at women, and women watch themselves being looked at. Laura Mulvey sharpened this into a cinematic scalpel, cutting through the celluloid illusions of the heterosexual male gaze. But what happens when the gaze shifts—not toward women—but toward men? What emerges when desire turns inward, and the watcher wants the watched not as other, but as mirrored flame?

This is the terrain of the homosexual male gaze—less overt, more coded. In a world hostile to same-sex longing, artists learned to speak in silhouettes. A shoulder glistening with oil. Fingers poised at the hem of a robe. Averted eyes thick with charge.

Within Orientalist painting, this covert glance found fertile ground. The excuse of “ethnographic interest” allowed artists to study male bodies—brown, muscular, mythologized—without suspicion. Desire cloaked itself in cultural inquiry. Intimacy was rendered foreign, and therefore permissible.

Yet beneath the layered drapery of empire’s imagination, longing persisted. These paintings are not simply artifacts of colonial fantasy; they are haunted mirrors of secret hunger. Their gaze may originate in power, but it drips with ambivalence—part admiration, part possession, part unspoken kinship.

In this subtle sleight of hand, Orientalist canvases become double-voiced: offering spectacle to the world, while murmuring seduction to those who knew how to read between the brushstrokes.

Key Orientalist Artists and Potential Homoerotic Themes

| Artist Name | Brief Description of Potential homoerotic Elements |

|---|---|

| Leon Bonnat | Composed scenes where male bodies languished in poised intimacy—close enough to stir, but still framed as custom. |

| Jean-Léon Gérôme | Painted soldiers at rest, bathers in marble chambers—nudity softened by ritual, but never neutral. |

| Léon Bakst | Dressed male dancers in fabrics that clung like heat, exposing not just skin but suggestion. |

| Anne-Louis Girodet | Infused myth with a slow, male shimmer—his figures half-angel, half-desire. |

Quiet Intimacies: Slivers of Homoerotic Undercurrents

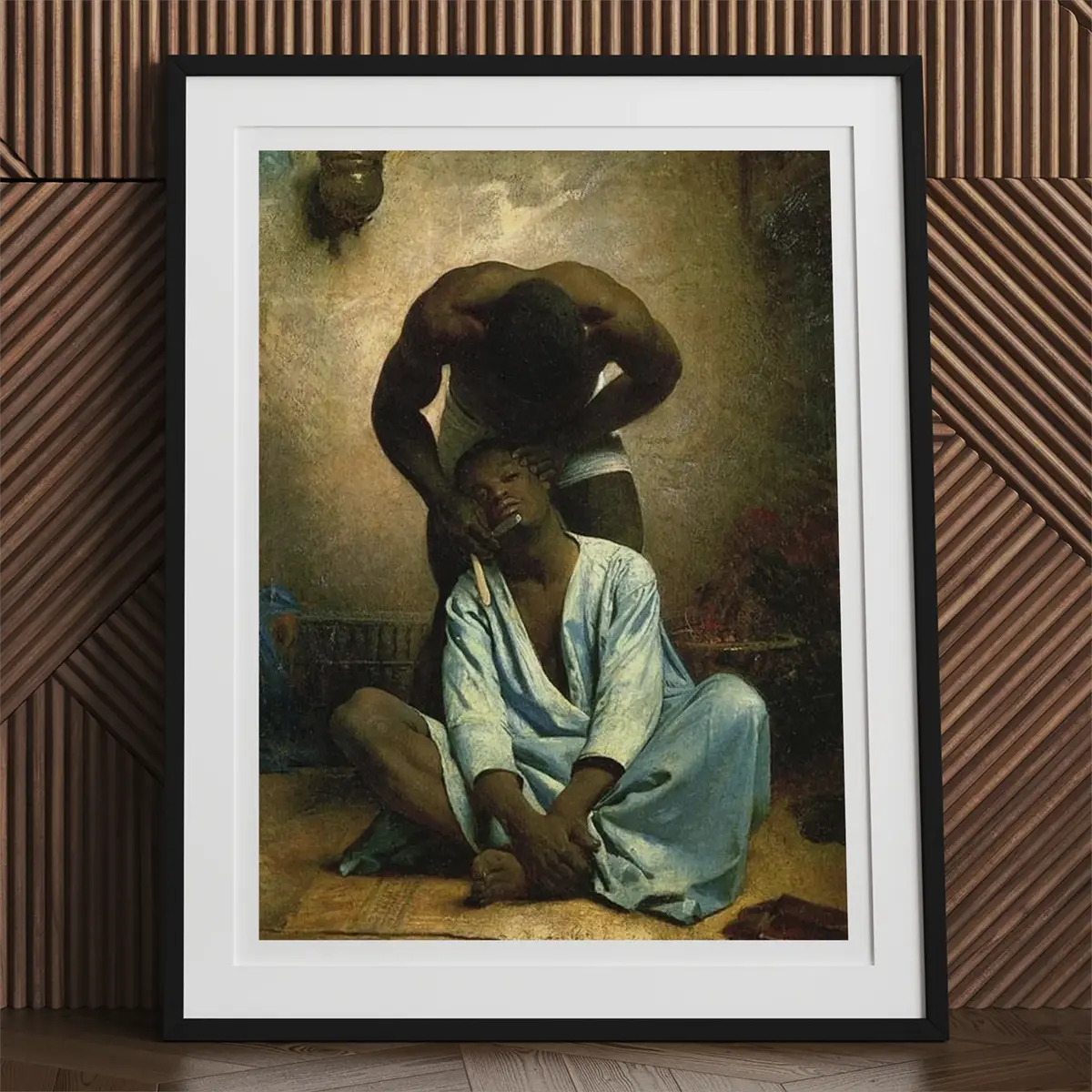

Leon Bonnat, The Barber of Suez (1876 CE)

In The Barber of Suez (1876), Leon Bonnat paints what first appears banal—a shave in a backstreet shop. But linger. The youth reclines not with the slump of habit, but with theatrical ease: robe parting just enough, neck arching toward the barber’s groin. Their closeness hums, unspoken. The razor poised near tender skin becomes not just a tool, but a metaphor—threat and thrill, danger brushed with desire.

This is the choreography of homoeroticism disguised as daily life. A staged accident of proximity. A Western artist feigning detachment while his canvas betrays a hungering eye.

Jean-Léon Gérôme, more canonized, no less suggestive. He painted men bathing, lounging, or polishing weapons in rhythms of bare muscle and careful shadow. His Orient was populated with bodies both idealized and inexplicably tender—masculine softness that never named its purpose but shimmered with implication. To view these scenes now is to question: what did Gérôme see, and what did he long to see?

Then came the stage. Under Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, Orientalism leapt into motion. Léon Bakst costumed Vaslav Nijinsky and other dancers in silks that barely veiled flesh. In ballets like Cléopâtre or Narcisse, male bodies became temples of curve and control—objects of both worship and erotic spectacle. These performances blurred empire and ecstasy, turning choreography into coded confession.

Each work, each gesture, was a sliver. But collected, they form a prism: refracting queer desire beneath the colonial gaze, burning quietly beneath silk and oil.

Beyond the Harem: Queer Female Perspectives and Sapphic Orientalism

Elisabeth Jerichau Baumann, An Egyptian Pot Seller at Gizeh (1876-78 CE)

If Orientalist art was often a man’s domain—framing veiled women through an eroticized lens of conquest—then Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann trespassed. Not with scandal, but with brush and access. She was one of the few Western women granted entrance to the harems of Egypt’s elite. Where Gérôme imagined, she witnessed.

Her encounter with Princess Zainab Nazlı Hanım was not voyeurism, but intimacy rendered in pigment. These weren’t just portraits; they were transactions of warmth. Flesh and silk. Eye meeting eye. Her paintings do not leer. They listen.

This is where sapphic Orientalism begins—not merely in content, but in method. Jerichau-Baumann painted from within, not from above. Her gaze lingered differently. Not colonial. Not carnivorous. But something like reverence, like recognition. The women she depicted seem neither oppressed nor objectified—they shimmer with agency, adorned not for display but for themselves, for each other, for a gaze that might also be female, also desiring.

Where male artists cast women as tableaux, Jerichau-Baumann offered collaboration. The brushstroke became an exchange, charged with quiet possibility. Critics now read these works as documents of a queer feminine gaze—not because they scream sapphic intent, but because they exhale it.

This defiance is subtle but seismic. Amid a genre dominated by men projecting fantasies of conquest, her work dares to imagine eroticism not as possession, but as communion.

And in doing so, she ruptures the smooth myth of Orientalism. Within those golden rooms and jasmine-scented silences, queerness bloomed—not in rebellion, but in relation.

Here, behind the harem’s ornate lattice, two women rewrote what longing could look like—and who it might belong to.

Homoerotic Traditions of the Middle East

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Pelt Merchant Of Cairo (1869 CE)

To imagine the East only as a surface onto which Western artists projected their desires is to flatten centuries of richly woven, internally cultivated expressions of same-sex intimacy. Homoeroticism was not a foreign imposition—it was already there, inked into verse, illuminated on vellum, whispered in gardens, and sung beneath the moonlight of Shiraz.

In Persian art and literature, beauty was never bound by binary. The beloved was often male: radiant, elusive, adorned. The ghazal—a poetic form thriving from the 9th century onward—spilled over with longing for the saqi, the wine-bearer, who offered not only drink but temptation. These were not hidden gestures; they were open acknowledgments of desire, veiled only by metaphor, as much for beauty’s sake as for discretion. Miniature paintings—detailed as dreams, luminous with pigment—captured this world: two young men exchanging glances, bodies folded into pleasure or ritual, tenderness sketched into silhouette.

In Ottoman culture, the tradition was no less vivid. The şehrengîz, or “city-thrill” poetry, exalted the radiant boys of Istanbul’s streets and baths, blending urban topography with erotic topographies of the body. In the 18th-century Hamse-yi ‘Atā’ī, same-sex acts between men were not merely depicted—they were narrated, contextualized, and sometimes celebrated. The manuscript’s miniatures are unflinching: men entangled not as fantasy but as history.

This frankness existed alongside contradictions. While some courts protected poets and painters, others punished the very behaviors these works immortalized. But even under pressure, the art persisted—evidence of a world where male beauty and male desire were not always taboo, and where eroticism was enmeshed with philosophy, mysticism, and aesthetics.

For 19th-century Western artists—steeped in repression and moral panic—such traditions offered both inspiration and projection. They found in these images not only license, but echoes of what their own cultures had buried. Yet too often, they misunderstood or misrepresented. What was once spiritual or symbolic became erotic spectacle. What was once an internal mirror became an external mask.

To understand Orientalist art, then, we must also understand the cultural soil beneath it—the texts, traditions, and taboos that predated colonial gaze. Homoeroticism in the Middle East was neither invention nor aberration. It was—like the poetry of Rumi, the paintings of Behzād, the sighs of the saqi—part of the architecture of longing itself.

Colonial Overtones: Desire, Domination, and the “Ethnographic Gaze”

Constantin-Jean-Marie Prevost, The Tattooing of a Sailor (1830 CE)

Every Orientalist canvas is a double exposure. Look once, and you’ll see a man—serene, bronzed, lounging in a courtyard bath. Look again, and the shadows whisper conquest. Not just of land, but of bodies. Of the right to observe, define, and consume.

As Edward Said taught us, the Orient was never simply a place—it was a performance. And the stage was propped up by empire. What masqueraded as “documentary” or “ethnographic” was often softcore dominion: a way of looking that turned human beings into aesthetic objects, their autonomy dissolved into silhouette and smoke.

Within this visual economy, the colonized male body became paradox: admired yet infantilized, desired yet diminished, eroticized yet regulated. A soldier might paint a bathing boy with exquisite tenderness, then enforce sodomy laws in the very city he sketched. This is the colonial contradiction in full bloom: to criminalize the act while preserving the image, to ban desire while basking in its aesthetic echo.

The “ethnographic gaze” was empire’s alibi. It cloaked voyeurism in curiosity, eroticism in scholarship. It allowed Western artists and audiences to indulge in forbidden glances by pretending they were looking at something else—science, anthropology, civilization.

But the power dynamics were never neutral. These men—often Algerian, Egyptian, Ottoman—posed under coercive arrangements of class, conquest, or desperation. Their beauty was not theirs to keep. It belonged to the frame, the buyer, the imperial archive.

And still, their images persist—eyes meeting ours across centuries, asking: who watched whom? Who owned what? What was taken under the guise of art?

This is not to erase the potential for queer connection in these images—but to complicate it. Even the most tender portrayals remain haunted by asymmetry. For every flicker of genuine admiration, there lingers the colonial infrastructure that made such looking possible.

Desire, in these works, is never innocent. It is always mediated by empire, its aesthetic pleasures fused with political violence. And the brush, like the bayonet, leaves a mark—one painted with longing, the other with law.

Toward Ethical Reflection: Revisiting Orientalism from the Present

Gabriel Morcillo Raya, Bacanal (1923 CE)

To revisit these paintings now is to enter a hall of mirrors. Every gleam of sensuality reflects another layer of distortion. Yes, there is beauty—oil thick with gold, textiles rendered with aching precision, skin aglow with sun and suggestion. But there is also the violence of context. Who painted these bodies? Who owned them? Who profited from their exposure?

Orientalist art asks us not only to admire but to reckon. The gaze it offers is never free-floating—it is tethered to the colonial machine that made such images possible. To see the homoerotic in these works is not to deny their queerness, but to interrogate its cost.

Were these paintings radical for smuggling same-sex desire into the public sphere? Or were they complicit in reducing that desire to stereotype—exotic, available, silent? Can we celebrate their subversions without excusing their complicities?

Contemporary artists have taken up this thorned mantle. Lalla Essaydi re-stages Orientalist scenes with Moroccan women inked in calligraphy—unreadable to the Western eye, resistant to translation. Her work is reclamation through refusal.

Photographer Sunil Gupta coined “camp Orientalism,” fusing queer irony with visual pastiche to expose the absurdities of colonial desire. His portraits do not merely parody—they unmask. They show us how easily artifice becomes ideology, how quickly eroticism slips into possession.

To ethically engage with Orientalist homoeroticism is not to discard it, but to sit with its discomfort—to ask who was silenced in the making of beauty. We must read these images like palimpsests, where every brushstroke obscures as much as it reveals.

Desire and domination, tenderness and theft, coexist uneasily in these gilded frames. If we look too quickly, we see only romance. If we linger, we see structure.

This lingering matters. It teaches us that art does not just reflect the world—it shapes it. And sometimes, it must be broken open to be understood.

The Massad Challenge: Questioning Western Constructs of Sexuality

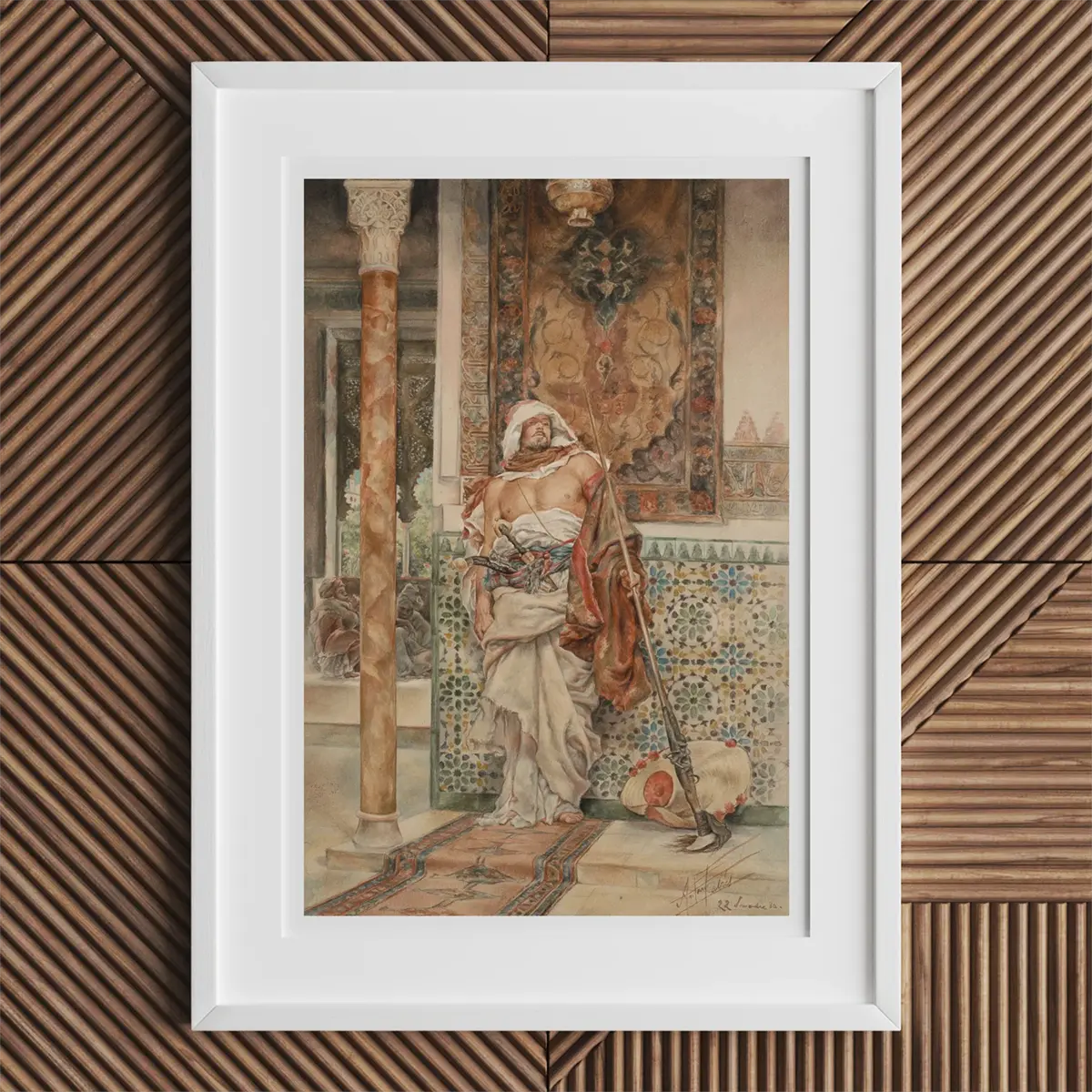

Antonio María Fabrés y Costa, The Palace Guard (1880 CE)

In the shadows of Orientalist oil and myth, another question smolders: how do we name desire? And who gets to decide what those names mean?

Enter Joseph Massad, the Palestinian scholar whose work lands like a tremor beneath the certainties of Western queer theory. In Desiring Arabs, he argues that the Western invention of “the homosexual”—as fixed identity, medical category, social type—was never a neutral export. It was a colonial imposition. A linguistic empire. And its deployment across the Arab world, even under the banner of liberation, often erased local understandings of intimacy that did not conform to binary or diagnostic models.

Massad doesn’t deny that same-sex acts occurred—he insists they did, abundantly, complexly. What he resists is the retroactive branding of these acts through a Western lens that insists on visibility, on categorization, on naming as salvation.

In Orientalist art, this provocation stings especially sharp. Were 19th-century painters truly engaging with Middle Eastern erotic traditions—or were they distorting them through the prism of their own repressed desires? When Gérôme painted a Turkish youth bathing, did he see the residue of şehrengîz poetry? Or was it simply a canvas onto which he projected his own forbidden longings, sanctified by distance?

Critics of Massad have called his framework essentialist or evasive. But his challenge remains a necessary friction: to what extent is queerness universal, and when does it become a form of cultural translation—sometimes illuminating, sometimes obliterating?

Western frameworks often require articulation: a confession, a declaration, a coming out. But many Middle Eastern traditions of male-male intimacy lived not in speech, but in gesture, in poetry, in passing glance. They were not less valid. They were differently legible.

So when we look back at these Orientalist images, we must ask: are we excavating queerness, or planting it?

Massad demands that we become cautious readers of desire—attuned not only to presence but to projection, to the ethics of interpretation, to the dangers of applying a modern Western taxonomy onto radically different historical soil.

His voice doesn’t close the conversation—it pries it open.

Contrasting Representations of Homoeroticism—West vs. Middle East

In Western Orientalist art, desire often wore a costume. It arrived draped in distance, couched in subtlety, justified through the language of “discovery” or “documentation.” The male body—usually youthful, often racialized—was not embraced, but staged. He appeared half-clothed in hammams, bowed in proximity, caught mid-movement in a scene ostensibly innocent. Yet each gesture shimmered with ambiguity. These works framed male intimacy not as love, but as spectacle—always tinged with colonial power, always half-veiled in plausible deniability.

Contrast this with the Persian miniature: not spectacle, but symphony. Painted lovers lock eyes without apology. Their gestures mirror the couplets of ghazals—verses heavy with wine, longing, and metaphysical ache. The saqi, wine-pourer and beloved, serves intoxication both literal and erotic, inviting viewers into a world where desire is not concealed but stylized into ornament and metaphor.

Ottoman art carved a third path: in the şehrengîz, the city itself became a catalogue of beauty, its neighborhoods mapped through the allure of boys bathing, dancing, or simply existing as embodied poetry. Manuscripts like the Hamse-yi ‘Atā’ī offered portrayals of sex between men with surprising candor, sidestepping euphemism altogether.

What Orientalist artists interpreted as taboo fantasy had, in many cases, already been canon. But filtered through Western eyes, it was fragmented—part eroticism, part ethnography, part empire. The difference lies not only in style, but in structure: one seeks to frame; the other, to feel.

| Key Characteristics | Examples/Motifs |

|---|---|

| Western Orientalist Art: Often subtle or implied, tinged with colonial objectification; sometimes masked as “ethnography.” | Proximity, suggestive poses, and a theatrical emphasis on youth and beauty |

| Persian Miniatures: Rooted in poetic traditions (ghazals) from 9th-20th century; beloved often young male. | Saqi motif, idealized lovers, spiritual and earthly intoxication |

| Ottoman Art: Manuscripts like the 18th-century Hamse-yi ‘Atā’ī depict sexual acts between men; şehrengîz poetry celebrating male beauty. | Military imagery as love metaphor, open portrayal of male intimacy |

Seeking the Threads of Desire in a Tangled Historical Tapestry

Antonio María Fabrés y Costa, The Palace Guard (1880 CE)

To gaze upon these 19th-century paintings is to enter a hall of contradictions—where beauty leans on violence, where longing passes through conquest, and where silence speaks volumes.

Orientalist art, in its most charged form, is not simply an archive of what was seen—but of what could not be said. The young man half-draped in linen. The soldier caught mid-wash. The dancer whose pose hovers between choreography and seduction. Each figure appears luminous, timeless. And yet, they are tethered—by brushstroke, by empire, by the voyeur’s eye that rendered them both object and ornament.

To uncover the homosexual male gaze in Orientalist art is not just to point out where desire hides—it is to understand the systems that required it to hide in the first place. These artists painted beneath the weight of criminalization, religious censure, and personal risk. So desire bled into the background. It curled into composition, pooled in shadow, waited behind a glance.

But longing does not disappear. It adapts.

At the same time, to exalt these works as brave acts of queer subversion without reckoning with their colonial complicity is to mistake the frame for the whole picture. These images are not neutral—they were made within empires that subjugated the very subjects they painted. And sometimes, eroticism became a weapon as much as a whisper.

We must hold these tensions together: that same-sex desire existed, pulsed, and even flourished in these works—and that its expression was often warped by the asymmetries of power, race, and access. The desire was real. So was the domination.

Meanwhile, artists in Middle Eastern traditions were already articulating queer desires with clarity and complexity. Persian poets inked erotic longing into verses that still smolder centuries later. Ottoman painters immortalized male lovers without apology or disguise. These weren’t fantasies—they were records of a world in which male-male intimacy could be sacred, literary, or simply lived.

What does it mean, then, that the West claimed to discover what the East had long expressed?

To interpret Orientalist art ethically requires more than decoding homoerotic symbolism. It asks us to confront our own desire for clarity—for categorization—for a clean moral arc. But these works are not clean. They are layered, ambivalent, exquisite, and troubled. They do not resolve. They flicker.

And perhaps that is the point.

Because desire, especially when entangled with history, is never simple. It trespasses borders. It survives repression. It makes itself known in brushstrokes and metaphors, in silences and seductions.

Within the folds of Orientalist paintings lies an archive of queerness—partial, problematic, radiant. Not just of who desired whom, but of how art has always mediated power, pleasure, and the politics of seeing.

To parse these images is to participate in a long tradition of looking back—not just to observe, but to understand what was at stake in the act of looking itself. Not just to find beauty, but to ask: whose beauty, for whom, and at what cost?