Within hushed galleries the world pretends art is courteous, yet its pulse is unruly — a daring ledger of adventure, being, inquiry, and witness. LGBTQ+ makers have forever inked that ledger.

Queer imagination keeps proving art is both outcry and archive. Time and again. Be it tomb‑mates Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep pressed nose to nose beneath desert stone. Harlem's coded jazz of Langston Hughes. The blazing sexuality of Moche ceramics. Zanele Muholi's steadfast glare. Cassils’ body‑as‑manifesto.

LGBTQ art is an unbroken braid of resilience, reinvention, and audacity through history. Each piece keeping vigil across centuries. Re‑igniting identity. Refusing erasure and lighting the raw fuse of possibility wherever eyes are willing to meet it. In their glow, history breathes. Insisting on wider, braver shared futures for all of us.

Key Takeaways

- A hidden continuum: LGBTQ+ expression is ancient — gracing Greek kraters, Roman silver, Egyptian tombs, and Moche clay — demanding we re‑evaluate how longing and identity bloom beneath censorious empires, century after luminous century.

- Cryptic symbols and codes: When candor risked imprisonment, queer makers wove green carnations, peacock eyes, violet sashes, and mythic aliases into paintings, poems, couture, and cabaret — secret constellations only the initiated could read.

- Crossroads of cultural shifts: From Renaissance anatomies reborn to Harlem’s syncopated blaze and the street‑shouting posters of the AIDS era, queer art charts every cultural quake, expanding hairline cracks into revolutionary boulevards.

- Activism through art: From illuminated parchment margins to courthouse marble, collectives like ACT UP, Gran Fury, and DIVA TV weaponized design — billboards, die‑ins, VHS reportage — turning private mourning into thunder that altered policy and hearts.

- Ongoing evolution: Today, the Leslie‑Lohman Museum, with Zanele Muholi, Catherine Opie, Cassils, Mickalene Thomas, Sin Wai Kin, and countless emerging voices, keeps the dialogue elastic, intersectional, and defiantly planetary — insisting queer art’s saga forever widens. Its compass now spans podcasts, NFTs, guerrilla murals, and virtual salons wherever courage speaks.

Defining and Contextualizing LGBTQ+ Art

LGBTQ+ art is not one style but a nebula of gestures, mediums, and voices that refuse a single orbit. Yet naming this constellation is tricky: across centuries, laws and gossip forced expression into sidelong glances and cryptic motifs. Painters tucked desire in the tilt of a wrist, poets stitched yearning between line breaks, weavers threaded tell‑tale hues through seemingly innocent patterns. A turned shoulder, a green carnation, a whisper of violet could signal truth and safeguard a secret.

Crucially, the vocabulary we lean on today — queer, lesbian, gay, transgender — did not crystallize until long after many works were made. To retrofit those terms without context risks flattening histories that deserve nuance. The very word “queer,” once hurled as a barb, has been repurposed as a banner of solidarity, proving language itself is an arena of resistance.

To study LGBTQ+ art, then, is to braid marginalized stories back into the wider tapestry of human creativity. It asks us to notice how exiled makers navigated hostile worlds, how they carved secret alcoves of expression under censure, and how their survival strategies now illuminate our collective archive. By reading these works attentively, we expand the record of who has shaped culture — and honor every identity that fought to be seen.

Echoes of the Past: Ancient LGBTQ+ Representations

Thread these ancient narratives together and the modern myth of queer novelty shatters. Longing reverberates beneath clay glaze, across hammered silver, in hieroglyphic margins, and inside bamboo‑fibred paper.

Each artifact — whether humble household charm or imperial treasure — extends a filament of solidarity across centuries, a gold seam stitched through empire, conquest, dogma, and revival.

Where edicts sought silence, art kept speaking; where missionaries swung hammers, shards kept remembering. To study them is to witness how the human urge for connection keeps surpassing every border raised against it.

The Complexities of Ancient Greece

Antoine-Christian Zacharie called Tony Zac, Female Companions of Sappho (ca. 1868)

...

Attic pottery sets our stage. Red‑figure kraters show a bearded erastēs courting a smooth‑cheeked eromenos with offerings — a rooster, a hare, a wreath. Symposium kylikes freeze philosophers trading riddles and flirtation. The active role crowned civic masculinity; the passive signalled youth, yet Myth upset every rule.

Achilles mourns Patroclus with spousal tenderness; Dionysus blurs decorum; Zeus, eagle‑borne, lifts Ganymede into circling constellations. On Lesbos, Sappho’s voice glitters through torn papyri, praising garlanded girls and the pulse of desire that outlives marble.

Vase painters recorded mentorship dinners, torchlight processions, and gymnasium games where oil‑sheened bodies debated virtue while admiring muscle. Courtship gifts echoed in poetry and law codes carved on stone steles.

Though female love seldom reached pottery, it thrived in song: Sappho describes a trembling heart “shaken like wind on the mountain” when another woman’s laughter steals her breath. Together these images prove that visibility relied on social power: citizens could indulge, slaves could not; youth would age into authority, lovers into memory; yet the art survives, unmoved by censure, offering future viewers a candid syllabus of ancient affection.

Prominent Examples

- Vase Paintings: Detailed imagery of male courtship, like an older man offering a small hare or rooster—a ritual gift symbolic of affection.

- Mythical Depictions: Achilles tenderly caring for Patroclus.

- Sappho’s Verses: Testimony to the vibrancy of female homoerotic devotion.

The Shifting Sensibilities of Ancient Rome

The Warren Cup (5–15 CE)

...

Rome inherited Greece’s legends but enforced its own etiquette. Martial and Juvenal mocked effeminacy while confessing appetite; Catullus poured longing for Juventius into honey‑barbed hendecasyllables. Penetrators claimed manly gravitas, the penetrated courted scandal. Yet art endured.

The Warren Cup, its silver surface verified by isotope test, depicts two male couples in tender congress, faces nearly domestic. Pompeii’s baths hide frescos of women entwined, though ash preserved more hetero revels. Hadrian’s beloved Antinous, drowned in the Nile, rose again in marble: down‑cast eyes, luxuriant curls, youth memorialized so often he rivals imperial gods.

Contradiction ruled policy: Senate edicts shamed certain acts while poets, patrons, and artists kept engraving desire into currency, cameo, and wall. In suburban taverns, graffiti tallied affections in meter; in the capital, weddings between men surfaced despite fog.

These traces show a society policing roles but captivated by reflection. Bronze hand mirrors, stamped with Ganymede, sold briskly at market stalls, souvenirs to hidden admirers and collectors far away.

Prominent Examples

- The Warren Cup: A prime example of explicit male-male intimacy in Roman decorative art.

- myth Depictions: Scenes of Ganymede and Jupiter (Zeus) illustrate how Greek narratives carried into Roman culture.

- Representations of Antinous: Beloved of Emperor Hadrian, portrayed in statues and busts that highlighted his youth and beauty.

Ancient Egypt: Nuanced Embraces

Bas relief in shared tomb of Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum (25th century BCE)

...

Near Saqqara, limestone reliefs in the shared tomb of Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum — royal manicurists under Pharaoh Nyuserre — show them touching noses and embracing waist to shoulder like husband and wife. Both had families, yet the artists foreground their tenderness, unsettling tidy genealogies. Scholars argue: dutiful brothers or devoted lovers? Either way, the scene widens what we imagine Egyptian intimacy allowed.

Occasional funerary spells warn against male‑male congress, proving the practice they condemn. Hints of women’s love are fainter — fleeting lines in medical papyri and playful songs — but even these ghosts broaden the Nile’s spectrum.

Elsewhere reliefs show gods shifting form, androgynous deities birthing creation, hinting at theological room for fluidity modern cynics overlook. While temple festivals featured cross‑dressing priests of Hathor and love spells invoked Sekhmet to bind hearts regardless of gender. Revealing practice alongside belief within village courtships too.

Prominent Examples

- Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum: Tomb imagery showing men locked in affectionate poses akin to spousal depictions.

- Limited References: Religious or funerary texts occasionally reference same-sex acts with caution, revealing the cultural ambivalence.

Ancient China: Romanticized Allusions and Deities

Chen Hongshou, Emperor Ai of Han cuts off his sleeve to not awaken Dong Xian (ca. 1651)

...

In Han China, calligraphy held stories paintings dared not. Emperor Ai let his lover Dong Xian sleep upon his robe, cutting the cloth away — duan xiu, the cut‑sleeve legend. Lord Ling of Wei tasting a peach bitten by Mizi Xia became another euphemism for male devotion. Tu Er Shen, the rabbit‑eared deity, blessed same‑sex vows from hidden shrines.

Folktales teem with shape‑shifting foxes and crane maidens sliding between genders like silk in wind. Confucian edicts later tightened decorum, yet album leaves show Ai and Dong walking beneath plum blossom, umbrella tilting their shared shadow.

Han medical guides include recipes for mutual pleasure sans seed, proving pragmatic acceptance under official restraint. While court chronicles speak of handsome courtiers promoted for beauty—bamboo slips recording verdicts that punished misconduct, not affection.

Prominent Examples

- Tu Er Shen: Deity explicitly linked to same-sex love.

- Han Dynasty Records: Known acceptance of bisexuality and homosexuality at imperial courts.

- “Cut Sleeve” Imagery: Emperor Ai’s legendary devotion immortalized in subtle portraiture.

Ancient Peru (Moche Culture): Wanton Expressions

Ceramic bottle shaped as copulating couple (1 - 800 CE)

...

On Peru’s desert coast the Moche shaped truth in clay. Stirrup‑spout bottles interred with farmers and warriors depict male‑male penetration, female‑female embraces, and multi‑partner tangles rendered with anatomical candour. Some scenes pair sex with sprouting maize or skeletal companions, fusing pleasure to cycles of fertility and mortality.

Scholars debate their role — fertility guide, cosmology text, erotic keepsake — but their sheer number signals everyday acceptance. Spanish missionaries condemned and shattered many vessels; yet fragments kept emerging from riverbeds, refusing erasure.

Modern Quechua villagers sometimes rebury shards in respect, acknowledging ancestors who saw no sin in diverse desire. While museum vitrines struggle to contextualise such explicit forms, but every surface declares that the body was once honoured without the veils imposed by later conquerors.

Prominent Examples

- Sexual Ceramics: Featuring male-male and possibly female-female encounters with clear, explicit detail.

- Social Integration: The frequency of such pottery implies normalized or at least recognized acceptance within Moche society.

Renaissance and Early Modern Period

Bridging Classical Influence and Renewed Curiosity

Guido Reni, Saint Sebastian (ca. 1615)

...

When Europe reopened the long‑latched cabinets of Greece and Rome, classical bodies walked back into art studios. Philosophers citing Plato’s ladder of love encouraged painters to linger on the male nude with a reverence that felt both scholarly and sensuous. Even Christian iconography bent: Saint Sebastian, bound to a post and punctured with arrows, became at once martyr and homoerotic muse, his soft torso glimmering under shafts of devotional light.

Inside elite palazzi an undercurrent of bisexual pleasure shimmered. Public dogma condemned sodomy, yet private salons—shielded by brocade curtains and generous patrons—let artists cloak desire in mythic fig leaves. A hint of Apollo here, a glance at Hyacinth there, and the canvas could thrill without drawing the inquisitor’s eye.

Illuminating Artistic Figures

Sodoma II, Benedict Repairs a Broken Colander through Prayer (ca. 1505-08)

...

Leonardo da Vinci, never explicit about identity, left notebooks and anatomical sketches showing tender proximity to male pupils. In 1476 an anonymous sodomy charge was lodged, then dismissed, but its shadow lingers over his androgynous Madonnas and eerie Saint Johns.

Michelangelo likewise glorified the male body—think of his marble David—and poured yearning into sonnets for Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, their Latin veiling desire behind allegory.

Il Sodoma—Giovanni Bazzi—boldly accepted the nickname “the sodomite,” scandalizing prudes yet still winning fresco commissions from Siena’s governors. Donatello, decades earlier, chiselled a bronze David of almost adolescent grace and prospered in a Florence where workshop whispers and Medici indulgence fostered same‑sex liaisons among craftsmen and courtiers behind carved walnut doors.

Women loving women surfaced only in flashes: whispered bathhouse sketches, a background gesture in tapestry, an anonymous pair distilled into the bustle of a festival fresco. Patriarchal scaffolds granted men louder legacy; female intimacy, when recorded at all, arrived veiled, seen through the male gaze. Yet those faint silhouettes prove that against every lattice of decorum, longing still found room to breathe.

Collectively, these artists reveal how Renaissance beauty masked forbidden undercurrents and how classical revival became a discreet lexicon for bodies and affections newly scrutinized by Church courts yet impossible to repress or censor.

A New Dawn: LGBTQ+ Expressions in the 19th and 20th Centuries

Coded Language and Symbolism

photograph-green_carnation_1200px.webp?v=1742875685" data-files="Oscar-Wilde-photograph-green_carnation_1200px.webp" data-caption="Framed portrait of Oscar Wilde." data-ai-alt="1" loading="lazy">

photograph-green_carnation_1200px.webp?v=1742875685" data-files="Oscar-Wilde-photograph-green_carnation_1200px.webp" data-caption="Framed portrait of Oscar Wilde." data-ai-alt="1" loading="lazy">

W. & D. Downey, Oscar Wilde (ca. 1889)

...

As industrial skylines rose and prudish lawbooks thickened, queer creators invented a covert semaphore of color, flora, and myth. A single green carnation, popularized by Oscar Wilde, could turn a lapel into a wink; a peacock feather, shimmering with rebellious vanity, fluttered in parlors from Paris to St Louis. Painters kept slipping Apollo and Hyacinth into salon canvases, or tucking Ganymede's yearning behind drapery—classical foils dignifying modern desire. Even echoes of ancient Athens resurfaced when admirers exchanged hares or roosters in polite society, cloaking erotic intent in antique ritual.

Colors grew tongues, too. Purple—soon lavender—spread through ribbons, stationery, and secret calling cards, its pastel hush proclaiming difference to any eye schooled in its code. By mid‑century, clandestine bars from Chicago to Sydney amplified that palette into the hanky code, declaring preference with chromatic precision: red for role play, navy for sailors, black for leather devotion. Even those who dared not speak could still declare—stitch by stitch and knot by knot.

These emblems formed an underground constellatory map; lovers and friends navigated its sparkle to find one another across a night sky of censure. The very act of ornament became resistance: beauty weaponized, elegance steeled.

The Harlem Renaissance (1920s–1930s): A Locus of Liberation

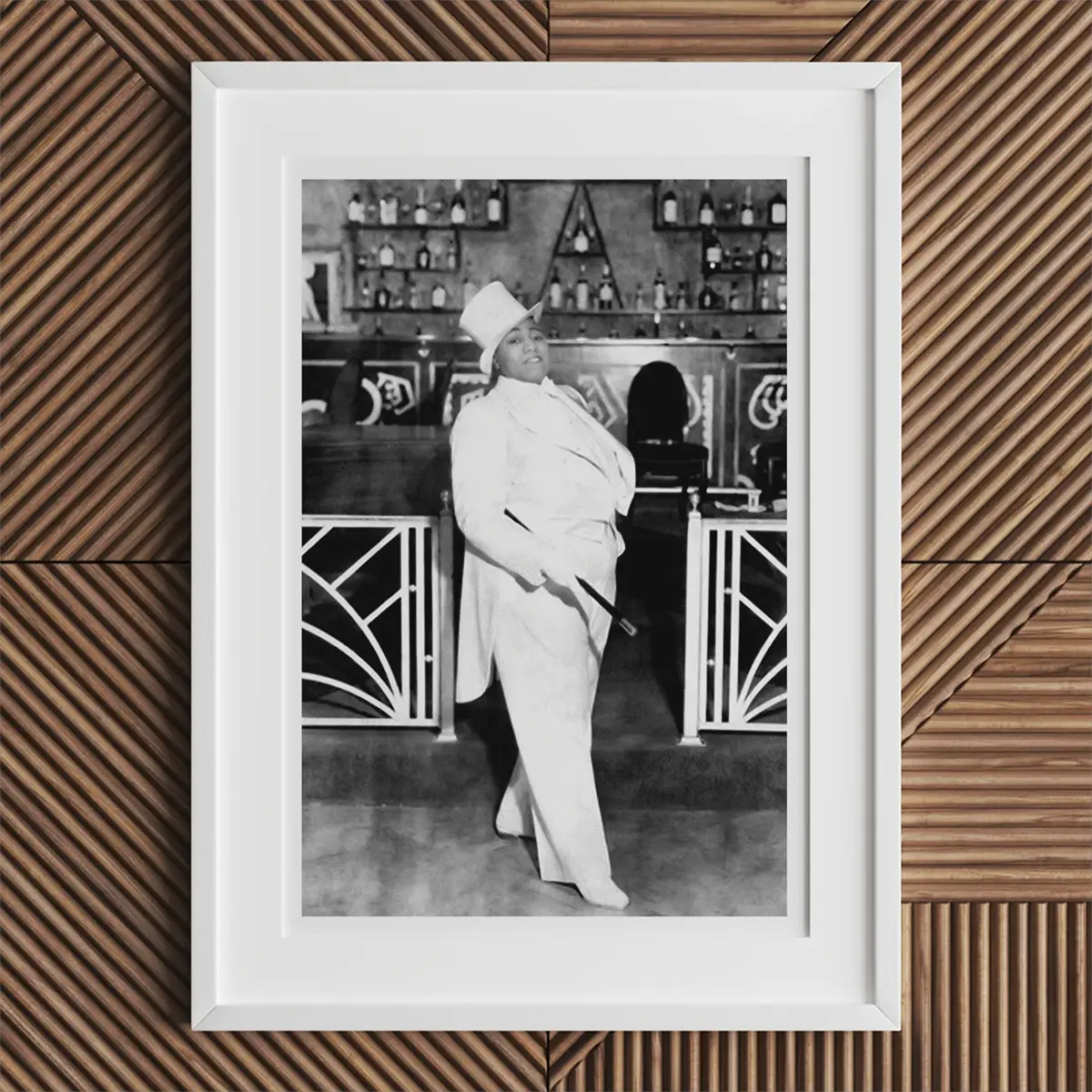

Michael Ochs Archives, Blues singer and pianist Gladys Bentley (ca. 1930)

...

Up in Harlem, where the Great Migration’s footfalls drummed Harlem River Drive and the cotton mills emptied dreams into jazz clubs, Black queer voices co‑scripted a cultural ephiphany. Langston Hughes laced blues cadences through poems whispering of unspoken yearnings and segregated solitude. Countee Cullen measured love against biblical strictures, while Claude McKay spiked his sonnets with defiant, immigrant‑flavored sensuality.

Novelist and bon vivant Richard Bruce Nugent flung the closet door clean off its hinges in Smoke, Lilies and Jade—a stream‑of‑consciousness nocturne chronicling bisexual rapture beneath a moonlit tenement roof. On stage, Gladys Bentley barreled into speakeasies in crisp tuxedo and top hat, pounding piano keys while singing of women who kissed back. Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith pressed 78‑rpm shellac with blues about stolen kisses and “bulldagger” lovers, sneaking sapphic confessions past White record executives deaf to subtext but hungry for sales.

Together, these writers and performers turned Harlem blocks into a kaleidoscope of race, sexuality, and modernist swagger. Rent parties, drag balls, and literary salons blurred lines between activism and artistry; every trumpet riff and typewriter clack insisted that Black queer life was not a pathology but a polychrome fact of the republic.

Prominent Harlem Figures

- Langston Hughes: Poetry that subtly addresses identity and alienation.

- Richard Bruce Nugent: Smoke, Lilies and Jade confronted bisexual themes head-on.

- Gladys Bentley: Gender-bending performances at speakeasies, enthralling and scandalizing audiences.

Beyond Harlem: Claude Cahun and Romaine Brooks

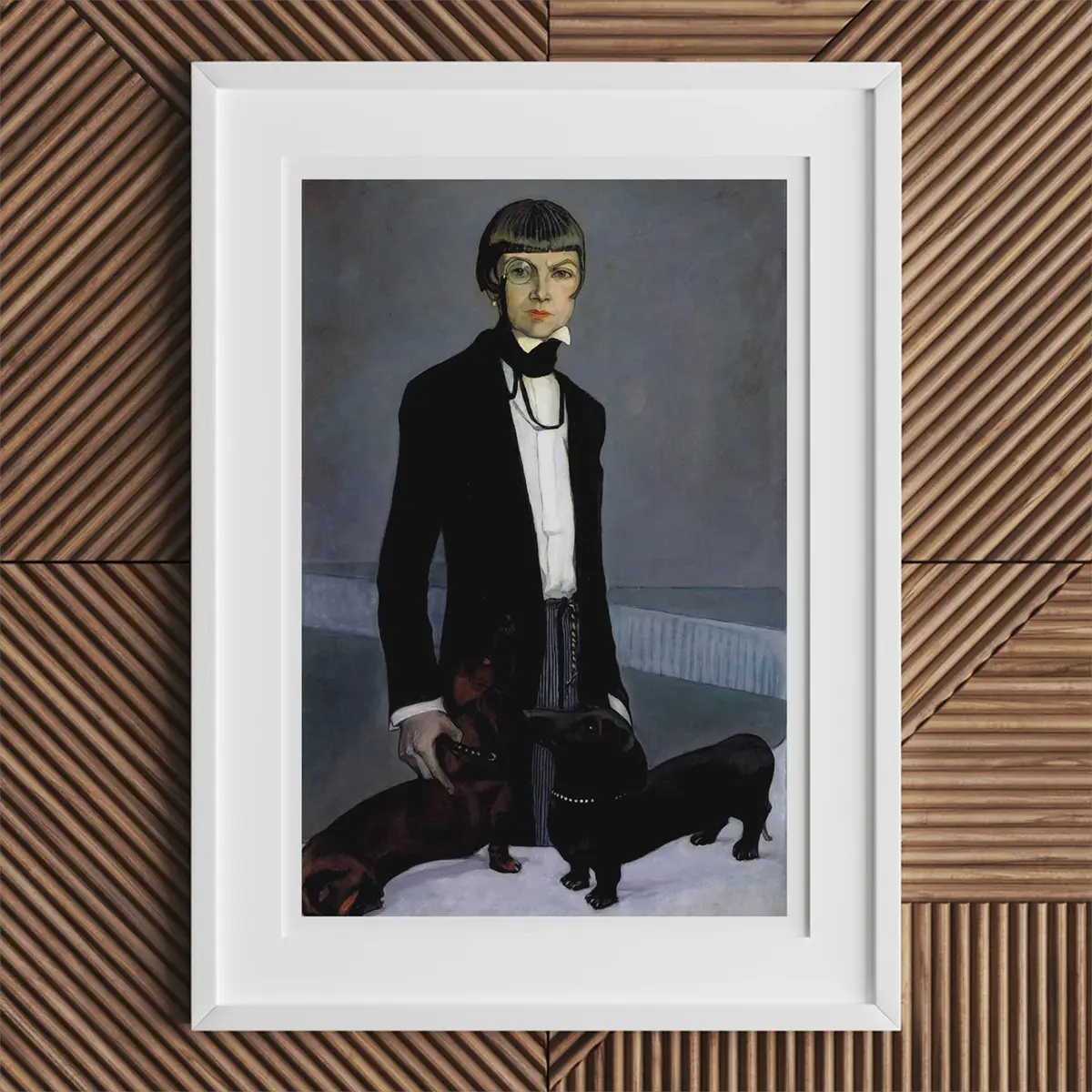

Romaine Brooks, Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge (ca. 1924)

...

Across the Atlantic, on France’s damp Normandy coast, Claude Cahun—born Lucy Schwob—posed before her camera in shaved head, painted brows, and costumes that dissolved gender like salt in rain. Her photomontages fused Surrealist fracture with Jewish mysticism, drafting blueprints for non‑binary futures decades before the language existed. By staging herself as boy, bride, androgyne, and sometimes sphinx, Cahun argued that identity is collage: cut, rearranged, re‑pinned with silver tacks of self‑determination.

Meanwhile in Paris studios and Italian villas, expatriate painter Romaine Brooks unfurled vast, ash‑grey canvases of solitary women in greatcoats—poised, aloof, defiantly un‑ornamental. The charcoal palette muted hetero expectations, letting queer subtext breathe in the hush between brushstrokes. Her sitters—writers, aristocrats, lovers—share a steel‑jawed gaze that meets the viewer head‑on, daring censorship to name the charge.

Brooks and Cahun never shared a gallery wall, yet their work conversed across distance: both used monochrome restraint to amplify interior tumult; both carved space for Lesbian and fluid selfhood in an art world distracted by Cubist geometry and Dada pranksterism.

Threads Converging

By 1939, when fascist shadows lengthened over Europe and segregation deepened stateside, the groundwork for later revolts was firmly anchored: a secret language of flowers and fabric; a literary chorus that refused erasure; photographic proof that the body was a manuscript one could edit at will. The next generations—Stonewall rioters, ACT UP poster brigades, digital activists hashtagging pride—would inherit these crumbs of color and myth, enlarging them into megaphones.

And so the new dawn glimmered not as a single sunrise but as constellations branch‑stitched across decades: quiet signals turned into orchestral blasts, jazz notes blooming into murals, closet whispers hardening into manifestos. The 19th and early 20th centuries did not merely foreshadow liberation—they supplied its palette knives, trumpet valves, and printing plates, ensuring every future shout of queer exhilaration had archival thunder rumbling underneath.

Pop Art as Queer Camp (1950s–1970s)

Subversion in Technicolor

ANDY WARHOL, Ladies and Gentlemen (ca. 1975)

...

When Abstract Expressionism filled Manhattan lofts with brooding spatters, a neon counter‑chorus flickered to life: Pop Art—all grocery‑aisle reds and billboard yellows—refused solemnity in favor of supermarket spectacle. Beneath that commercial gloss, queer ingenuity thrummed, turning everyday icons into covert manifestos.

The movement’s British seed sprouted in the Independent Group, where Richard Hamilton collaged magazine clippings into sly homoerotic puzzles: bodybuilder torsos sharing frame space with futuristic appliances, masculinity soldered to marketing. Crossing the Atlantic, Pop erupted in hot‑rod hues and Hollywood afterimages. Andy Warhol, Pittsburgh printer turned silver‑wigged oracle, screen‑printed Campbell’s cans until banality sang—then shifted to bodies: Torso silkscreens, Cowboy films, Polaroids of drag luminaries backstage at the Factory. Repetition became camouflage; camp became critique.

Meanwhile, David Hockney swapped England’s damp greys for Los Angeles aquamarine, painting sun‑shattered pools where naked men lounge, domesticating erotic tenderness at a time when U.K. courts still criminalized it. Across the studio floor, Robert Indiana stacked four bold letters—LOVE—tilting the “O” so affection looked perpetually off‑kilter, the slyest valentine Broadway never noticed.

Back in swinging London, Pauline Boty, the so‑called “First Lady of British Pop,” collaged pin‑ups, lipstick, and call‑girl telephones, splicing feminist fury with queer sensuality; her canvases radiate strawberry‑milk audacity that male critics dismissed as frivolous, misunderstanding camp’s armor.

Consumer Camp

David Hockney, Man in Shower (ca. 1964)

...

Pop’s genius was to hijack Madison‑Avenue sparkle. Borrowing Susan Sontag’s description of camp as a love of exaggeration and artifice, Pop artists embraced “too muchness”—and queer spectators recognized the strategy. Warhol’s gold‑leaf Marilyns parody sainthood and desire in the same breath; Hockney’s glossy swimmers refract sunlight and longing; Indiana’s typographic totems sell romance like detergent but quietly question who gets to love whom in public.

Blurred boundaries let coded critique survive censors: a Coca‑Cola bottle might echo phallic bravado; a Xeroxed Elvis could mirror faceted identities; a pastel cadmium pool could double as Eden for exiled bodies. By saturating the gallery with Americana excess, queer Pop artists smuggled subtext past gatekeepers who mistook glam for surrender.

Key Artists and Contributions

Pauline Boty, Sunflower Woman (ca. 1963)

...

Andy Warhol: Redefined artistic celebrity at his Factory; infused consumer imagery with coded queer critique, using repetition and camp to dismantle traditional notions of authenticity.

David Hockney: Brought explicitly gay themes into mainstream art at a time when homosexuality was criminalized in the UK, using bright, California-inspired aesthetics to normalize queer desire.

Robert Indiana: Created the iconic “LOVE” sculpture, subtly embedding personal identity within a universally celebrated image, quietly advocating queer acceptance.

Pauline Boty: The “First Lady of British Pop” who infused feminist critique and subversive sexuality into collages and paintings, challenging gender roles and celebrating female desire.

Pop’s palette, then, was never neutral; it crackled with coded frequencies. Drag queens posed for screen tests while gossip columnists chased film stars; silkscreens of soup financed underground movies starring trans muses; Hockney’s poolboys rippled into suburban living rooms, destabilizing hetero décor.

By the 1970 Stonewall riots, Pop’s arsenal—mass production, irony, celebrity—had proven ideal for activism. Future collectives like Gran Fury would remix Warhol’s repetition into AIDS‑era agit‑prop; Hockney’s unapologetic couples paved runways for queer advertising; Indiana’s LOVE sculpture metastasized into pink‑triangle remixes, turning tenderness into protest.

Thus Pop Art’s candy shell concealed barbed insistence: every soup can a coming‑out leaflet, every Ben‑Day dot a Morse code syllable spelling freedom. In technicolor excess, queer camp found a mirror ball—spinning, reflecting, dazzling—illuminating identities the art world had tried to keep in shadow.

From Oppression to Pride: Reclaimed Symbols

Gay Liberation Front (ca. 1970)

...

When regimes sharpened the tools of repression, queer communities learned to reverse the blade—polishing stigma into signal, wound into banner. Nowhere is alchemy clearer than in the pink triangle. In Nazi camps it marked men forced into murderous labor; stitched upside‑down on striped uniforms, it conspired with barbed wire to dehumanize. Yet by the 1970s, activists flipped the triangle upright, dyed it valiant fuchsia, and stamped Silence = Death beneath—an act of memorial and mobilization. Every rally poster bearing that icon whispered both elegy and war‑cry: we survive, we testify.

Not long after, the lambda (λ) leapt from physics textbooks onto placards. Chosen in 1970 by the Gay Activists Alliance, the letter’s classical breadth evoked balance and change; in medieval heraldry it symbolized justice in the face of adversity. Sewn onto jackets, carved into rings, the lambda signaled liberation’s equation: visibility multiplied by persistence equals transformation.

Other emblems galvanized in tandem. Twin interlocked female circles (double Venus) and male arrows (double Mars) transcended astrology to visualize affinity unchecked by straights’ scripts. Pinned discreetly to denim lapels or painted across bar walls, they rendered solidarity legible at a glance—geometry as fellowship. In San Francisco, purple ink stained policemen’s gloves during a 1969 protest, inspiring the Purple Hand: print of resistance slapped across newspapers and storefronts, warning authorities that queer bodies would not blanch at bruises.

Color itself remained code. Lavender—once cocktail chatter slang for sissies—was rehabilitated in marches, scarves, and theater curtains, proclaiming calm defiance. Decades later, the rainbow flag synthesized these fragments: Gilbert Baker’s 1978 sewing machines churned stripes of hot pink, red, orange, yellow, green, turquoise, indigo, and violet, each hue keyed to life, healing, sunlight, nature, magic, serenity, and spirit. As supply shortages trimmed colors, marches kept fluttering, proof that essence survives edit.

Reclamation did more than invert shame; it re‑engineered collective memory. Each reused symbol braided grief into strategy, ensuring martyrs were neither forgotten nor exploited solely as sorrow. Activists taught future generations to interrogate every badge, to ask: Who first wielded this shape against us, and how can we reforge it for joy?

Thus oppression’s lexicon became pride’s dictionary: triangles upright, lambdas radiant, doubled glyphs entwined, and purple palms raised like votive candles against the dark. Every icon carries archived struggle, but also kinetic possibility—portable monuments ready to march, chant, and shine wherever new injustices cast their predictable shadows.

Art as a Weapon: the Aids Crisis and Activism (1980s–1990s)

A Moment of Gravest Peril

Silence = Death Collective, Let the Record Show (ca. 1987)

...

By 1981 a new illness crept through queer and trans circles in New York, San Francisco, Montréal, Sydney—stealing weight, voice, breath. Newspapers coined it “gay cancer,” politicians folded hands, pulpits thundered retribution. Friends became elegies overnight; obituaries crowded weekly tabloids like storm warnings. Yet while hospital corridors echoed with silence, artists flooded streets with color, rage, and data—converting grief into artillery.

ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) gathered in 1987 at the lesbian & Gay Community Services Center on 13th Street: playwrights, nurses, drag queens, bond traders, mad poets—united by fury at pharmaceutical delay and political bafflement. Their visual arm, Gran Fury, hijacked Madison‑Avenue polish: billboards blistered with tabloid headlines (Kissing Doesn’t Kill), subway cards re‑mixing Benetton ads, the inverted pink triangle over black emblazoned with Silence = Death. Every poster turned commuters’ commutes into ethics exams.

Videographers in DIVA TV lugged camcorders to candlelight vigils and die‑ins, splicing footage into public‑access broadcasts that countered White House indifference. Their grainy tapes preserved truth in real time, a scrolling epitaph no network anchor dared read.

Canadian trio General Idea re‑tooled Robert Indiana’s LOVE design into a crimson “AIDS”—letters tilting toward collapse—screen‑printed on posters, wallpaper, even stationary, forcing the acronym past denial into domestic space. The word became inescapable, a chorus line of ghostly red capitals.

Personal Loss, Artistic Resolve

Keith Haring, Untitled (ca. 1988)

...

Keith Haring—already famed for radiant stick figures—painted barking dogs and flying saucers around condoms, turning New York’s subway into an open‑air sex‑ed classroom. His chalk bodies danced yet warned; arrows pointed to responsibility, not shame.

David Wojnarowicz scorched canvases with collaged maps and broken crucifixes, radio towers spitting flame across empires of hypocrisy. His essay “Close to the Knives” shattered any illusion that art could remain apolitical when friends were dying by the dozen.

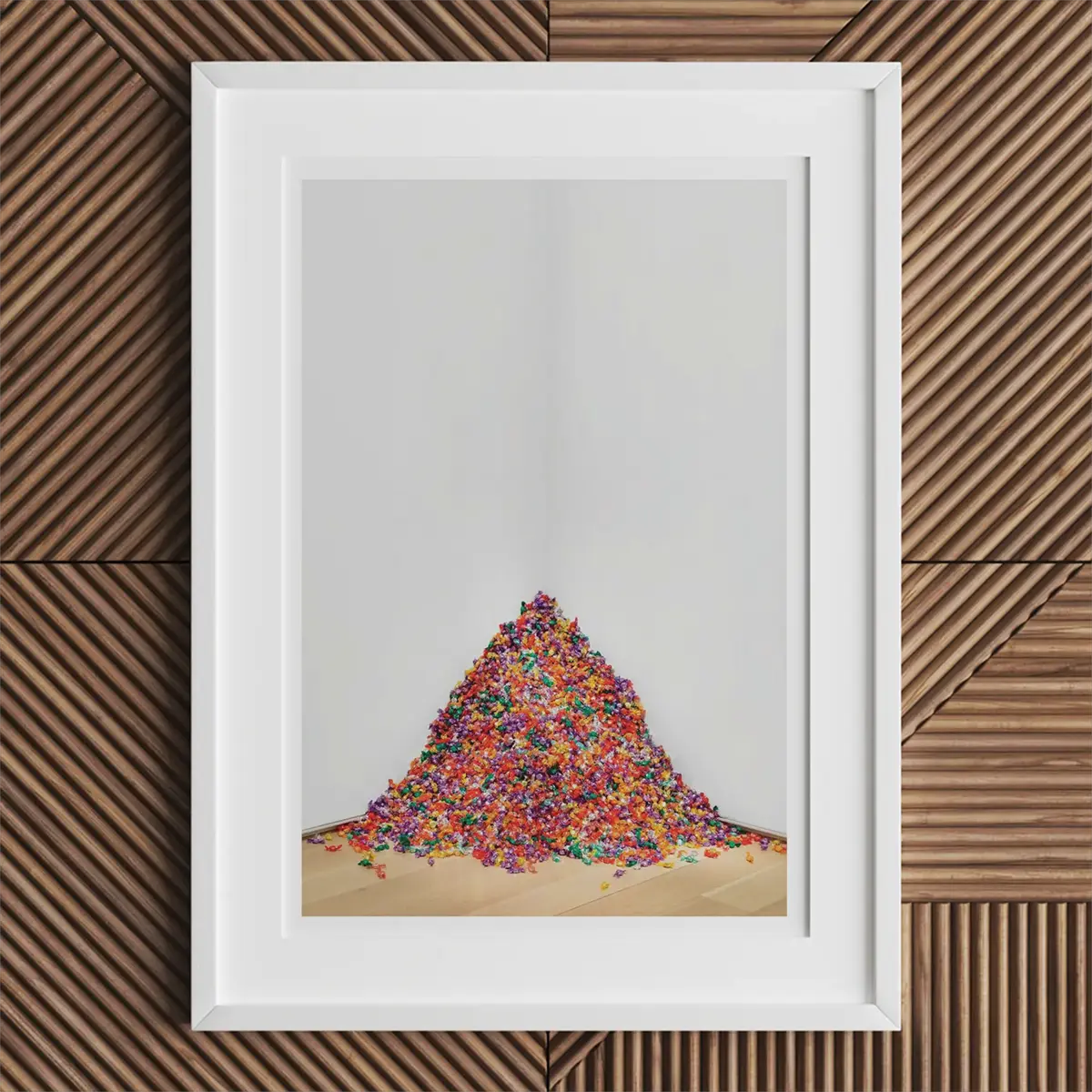

Felix Gonzalez‑Torres piled one‑pound candies into gleaming mounds—Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.)—inviting visitors to take pieces until the heap melted to nothing, mirroring his partner’s wasting body. Sweetness met attrition; participation bred empathy.

Nan Goldin aimed her lens at bedside vigils and drag‑house kitchens where IV stands tangled with Christmas lights. The intimacy of her slideshows—projected in clubs still pulsing with disco—forced revelers to stare into the epidermis of loss.

Volunteers behind the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt stitched 6‑by‑3‑foot panels—each the size of a grave—into an acreage of fabric sorrow spread across the National Mall. Walk the quilt and you walk a city of vanished laughter: sequined cowboy boots next to Star Trek insignias, Bible verses sewn beside glitter lipstick prints.

Key Artists/Collectives

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) (ca. 1991)

...

Art leaked outside museums: onto courtroom steps, FDA lobbies, the trading floor of the New York Stock Exchange. Die‑ins collapsed bodies onto asphalt like battlefield cartography; “Day Without Art” blacked out gallery walls each December 1st, teaching absence by enacting it. Wheat‑pasted posters listed congressional foot‑dragging in Helvetica tall enough to eclipse storefront signage. Designers recast CDC charts as neon infographics, proving statistics can cry out louder than elegy.

-

Gran Fury — Silence = Death, Kissing Doesn’t Kill

-

ACT UP — die‑ins, street zaps, FDA takeovers

-

DIVA TV — raw video chronicles countering mainstream neglect

-

Keith Haring — subway condom campaigns, safe‑sex murals

-

David Wojnarowicz — incendiary collage, political essays

-

Felix Gonzalez‑Torres — candy spills, light strings as love elegies

-

Nan Goldin — intimate photo‑diaries of care and mourning

-

NAMES Project Quilt — largest community artwork in history

-

General Idea — “AIDS” logo reframing pop iconography

Through posters, film loops, sugar heaps, fabric fields, and chalk‑lined hearts, the AIDS generation proved art can break a silence lethal as any virus—and that once broken, the echo never stops reverberating.

Enduring Imprint

By the mid‑1990s triple‑therapy drugs began to stem the tide, but activist aesthetics had already rewired visual culture. Every Pride parade banner, every social‑justice meme, every Instagram carousel quoting health stats owes lineage to AIDS‑era strategists who fused design with life‑saving urgency. The pink triangle remains—now upright, luminous—testament that symbols can be flipped, re‑charged, marched.

Artists taught governments to count bodies, newspapers to name lovers, families to claim ashes. They proved that posters on plywood can bend policy, that a quilt can out‑speak marble memorials, that grief wielded collectively becomes architecture. The crisis scarred generations, yet also minted the visual grammar by which public health—and queer resistance—communicates today.

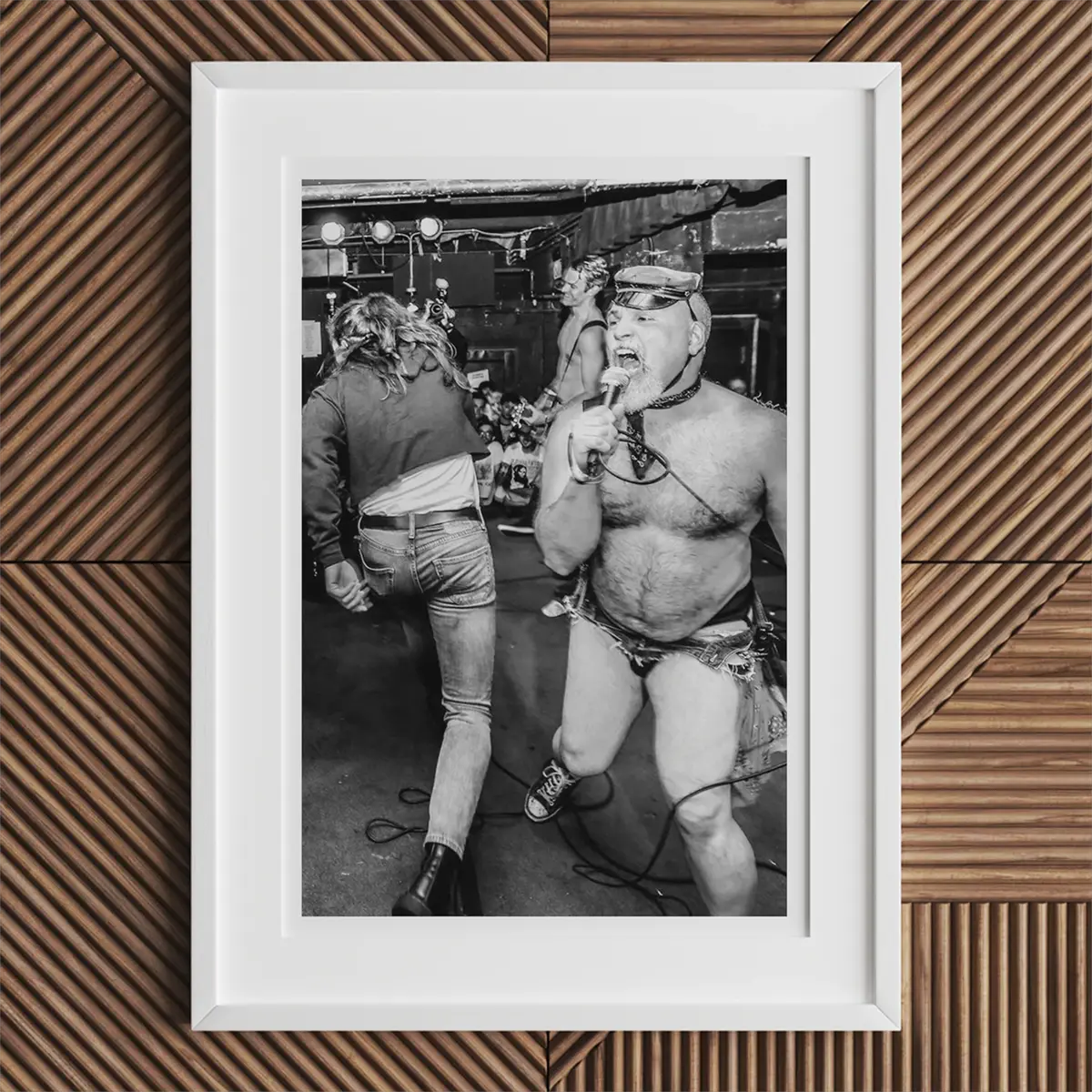

Punking the Mainstream: the Queercore Art Movement (1980s)

A Radical Offshoot of Punk

Farrah Skeiky, Martin Sorrondeguy fronts queercore band Limp Wrist (ca. 2018)

...

By the mid-1980s, the punk scene’s snarling promise had already begun to fray at its edges—its anti-establishment ethos increasingly compromised by homophobic gatekeeping and misogynist rot. Simultaneously, a growing number of LGBTQ+ youth felt alienated from the assimilationist tendencies rising within mainstream gay culture. In this crack between movements, something raw and defiant took root: Queercore—a movement that turned zines into lifelines, soundchecks into manifestos, and basement gigs into battlegrounds for liberation.

Fuelled by fury, alienation, and irreverence, Queercore didn't seek permission. It ripped queerness out of sanitised advocacy campaigns and threw it back into mosh pits and Xeroxed pamphlets. It mashed punk’s urgency with an unrepentant embrace of sexual and gender diversity. If punk was rebellion, Queercore was rebellion with a mirror—and glitter smeared across its cracked surface.

Queercore wasn’t simply about what you screamed, but how you lived. Its practitioners rejected polished, corporate-friendly representations of gay identity—those tidy narratives of quiet respectability—for something more unruly, more feral. They channeled their truth into screeched lyrics, deliberately lo-fi design, and performance art that weaponised camp and chaos.

Bands, Zines, and Visionaries

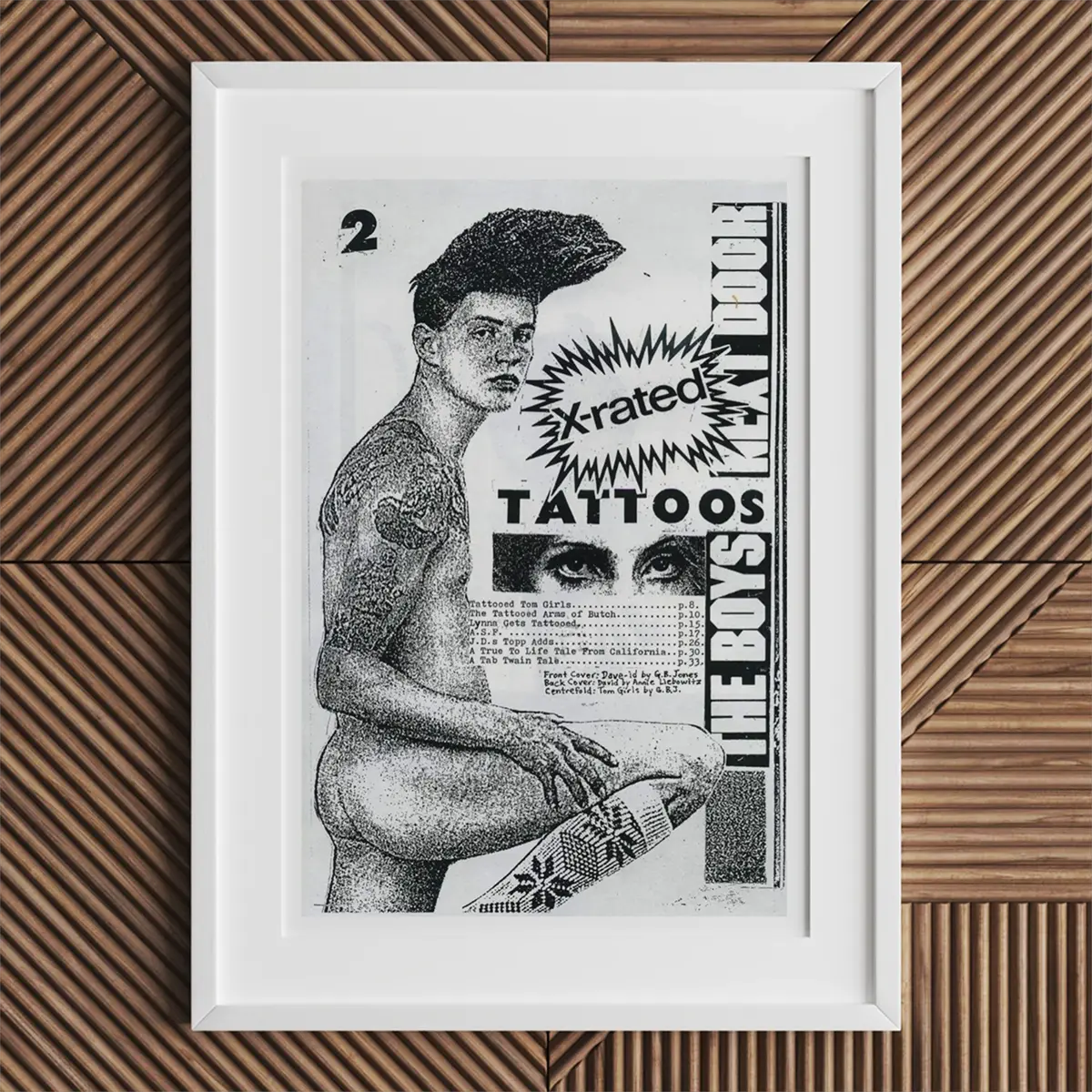

Bruce LaBruce, J.D.s (ca. 1985)

...

At the heart of Queercore beat a printing press and a photocopier. Zines, self-published and irreverent, became arteries of connection for a scattered yet fiercely passionate community. Among the most influential: J.D.s, edited by G.B. Jones and Bruce LaBruce, was part graphic epistle, part anarchic whisper network. It folded queer sex, film theory, manifestos, and misfit poetry into black-and-white pages that travelled across borders in unmarked envelopes.

These zines didn’t just critique the mainstream—they created an alternative to it. They offered messy, explicit, DIY snapshots of queer life outside respectability: hand-drawn covers, typewritten letters, grainy photocopied photos—screaming, we exist, and we don’t need your permission to thrive.

Meanwhile, bands like Fifth Column, Pansy Division, and Tribe 8 shredded guitars and gender norms in equal measure. Fifth Column, rooted in post-punk feminism, railed against the double binds of gendered violence and heterosexist boredom. Pansy Division, all leather, wit, and unrepentant sex-positivity, sang about cruising and heartbreak with power-pop sparkle. And Tribe 8, ferocious and fearless, took the stage with strap-ons and screams, reclaiming space for queer femmes in punk’s testosterone-soaked arenas.

Performance artists like Vaginal Davis turned dive bar stages and warehouse venues into theatrical battlegrounds. In towering wigs and low-budget glamour, Davis parodied conservative America, gay elitism, and colonial whiteness—simultaneously. Her persona was riotous and intellectual, raunchy and critical, refusing all binaries. Like Queercore itself, her art dared you to look—and then punished you if you did.

Though Queercore never charted on Billboard or earned mainstream grants, its defiance reverberated across generations. It laid a foundation for riot grrrl, informed the aesthetics of drag kings, and shaped the tone of queer film festivals and alternative galleries for decades to come.

Contemporary Voices: LGBTQ+ Art in the 21st Century

Diverse Forms, Global Reach

Zanele Muholi, Qiniso, The Sails, Durban (ca. 2019)

...

As the century turned, LGBTQ+ art didn’t simply evolve—it ruptured and reassembled, pushing past old borders to inhabit new mediums, new identities, new ways of seeing. In a world splintered by hyperconnectivity and disconnection alike, queer artists rewrote the rules—not just of gender, but of form, narrative, and visibility itself.

Now, identity is no longer confined to portrait or pronoun. It pulses through performance art, flickers across smartphone screens, unspools in virtual galleries. Artists explore queerness not as a subject, but as a method—nonlinear, fluid, boundary-defiant. The self becomes staging ground and battleground, soft skin rendered in hard light, fragmented across installations that refuse tidy resolution.

Crucially, today’s LGBTQ+ art addresses more than sexuality or gender. It confronts the braided systems of power—race, class, colonialism, climate crisis—revealing how queerness is entangled in every intersection of struggle. Where some states criminalize dissent, queer artists make it undeniable. In others, they rise in institutions once designed to erase them.

The internet has atomized the gallery wall. A performance in Johannesburg ricochets into Tokyo by morning. A zine posted in Oaxaca might reach a queer teenager in Jakarta. Marginalized voices no longer wait for institutional validation—they publish, perform, and provoke in digital spaces where visibility itself becomes a radical act.

Key Figures and Their Contributions

Sin Wai Kin, Change (film still) (ca. 2023)

...

Zanele Muholi

A visual activist from South Africa, Muholi’s black-and-white portraits of Black Lesbian, gay, and transgender people stare directly at the viewer—unflinching, unafraid. In their ongoing series Faces and Phases, the gaze is reversed: the once-objectified now observes, commanding presence in a world that rendered them disposable. Through archival rigor and visual lyricism, Muholi reframes survival as ceremony.

Catherine Opie

A chronicler of chosen families and queer domesticity, Opie documents subcultures with a cool eye and deep heart. Her portraits of leather dykes and pierced bodies resist both exoticization and normalization. Her Freeways and Mini-malls offer a queer geography of Los Angeles—personal, political, sprawling. In Opie’s lens, queer life is neither spectacle nor shadow; it is structure.

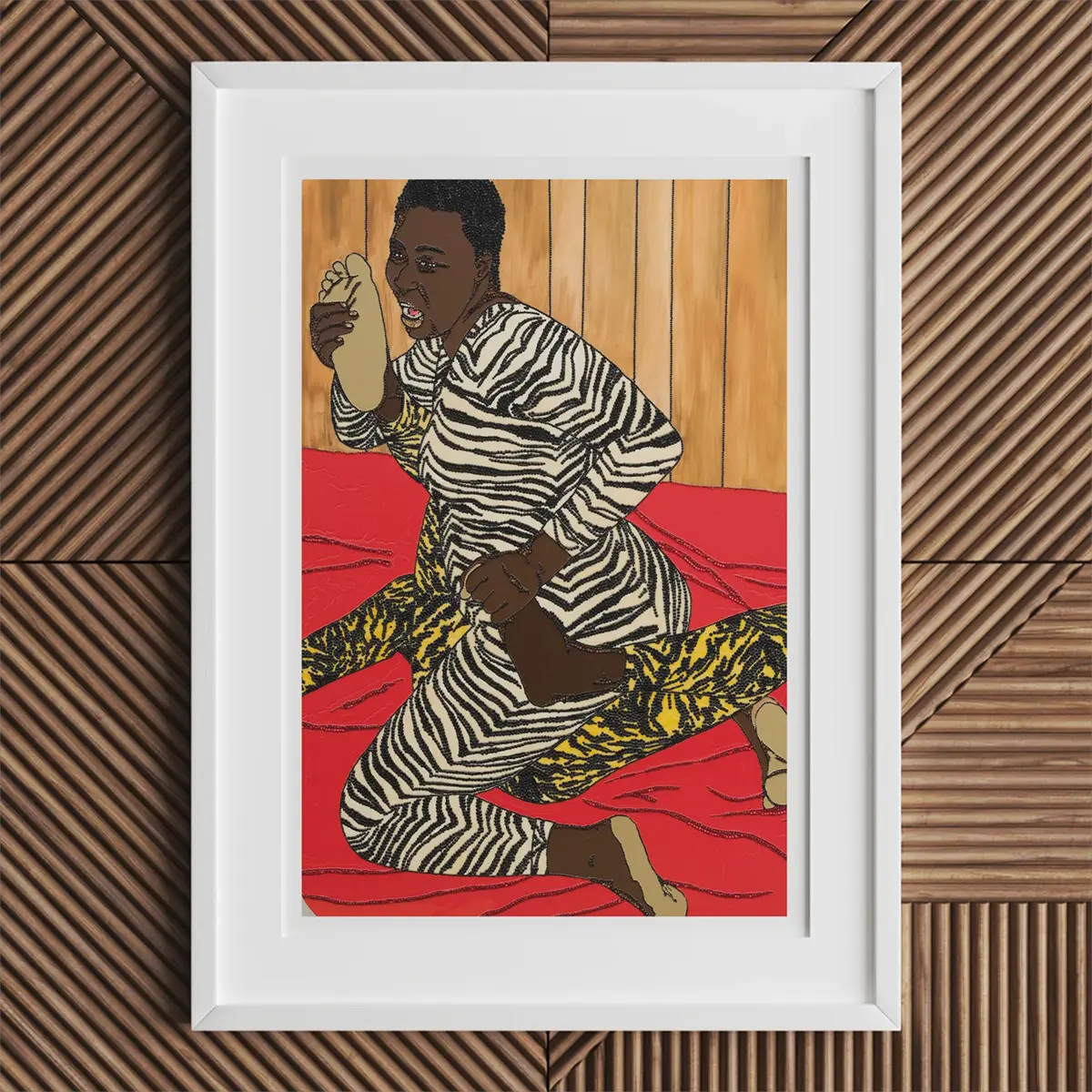

Mickalene Thomas

With rhinestones and collage, Thomas crafts worlds where Black femininity luxuriates in power. Her bold, color-drenched portraits explode art-historical expectations—evoking Manet’s Olympia while re-centering Black, queer beauty. Her work oscillates between glam and intimacy, reflecting on memory, desire, and the glamour of Black queer survival.

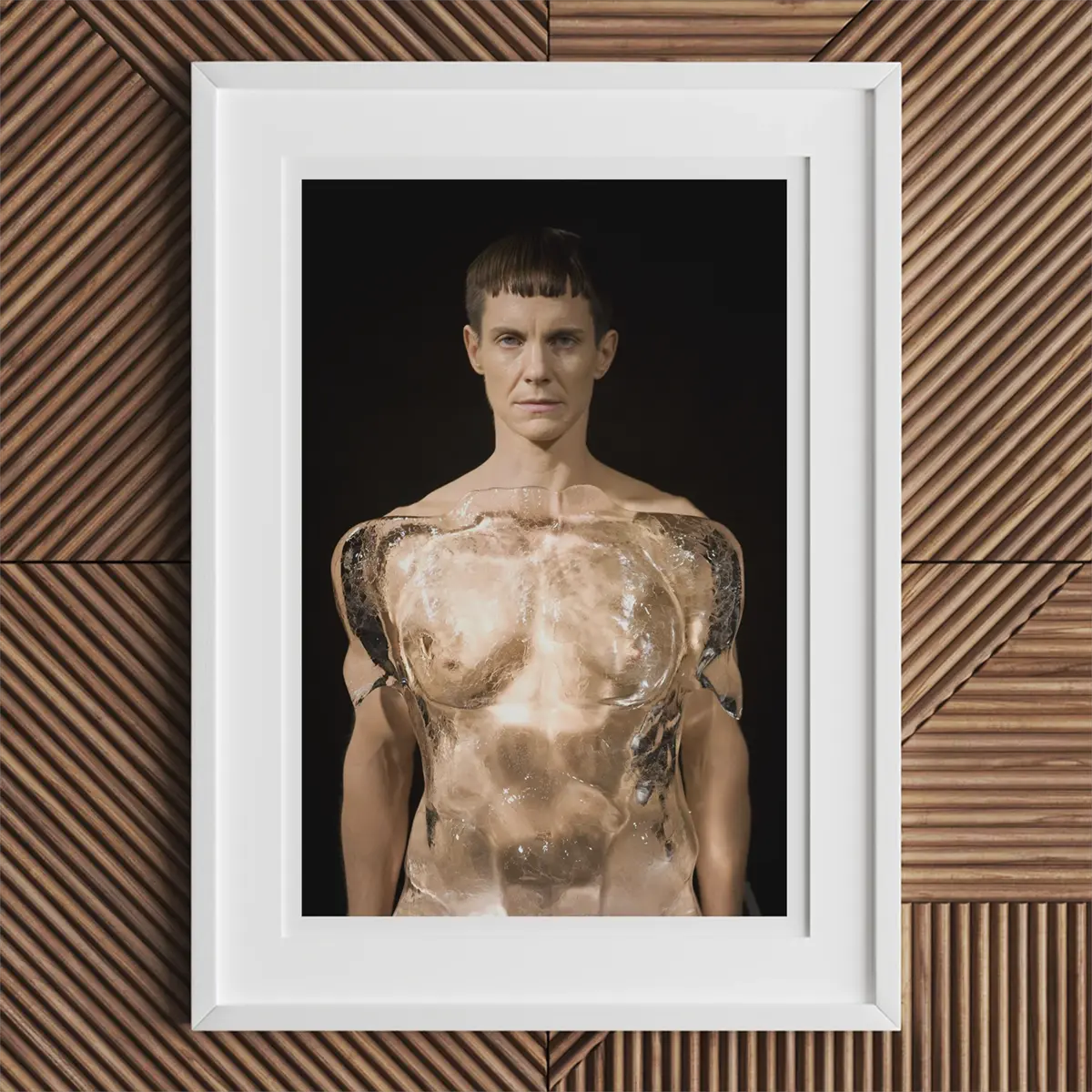

Cassils

A performance artist whose own trans body becomes site and statement, Cassils subjects themself to punishing acts of endurance. In Becoming an Image, they strike a clay block in darkness—the act illuminated only by camera flash—rendering violence both visceral and ephemeral. Their work doesn’t ask to be witnessed; it demands confrontation.

Sin Wai Kin

Fusing drag, speculative fiction, and Cantonese opera, Sin destabilizes the narrative scaffolding of gender and myth. Their surreal performances and videos blur character and performer, dream and critique. Whether as glittering oracle or cosmic narrator, Sin creates new cosmologies where gender is not fixed but unfolding, like a flower blooming backward in time.

Continuums and Counterpoints

While the spotlight illuminates new names, it also casts long shadows back toward late 20th-century visionaries. Felix Gonzalez-Torres, whose installations of candy piles and paper stacks once whispered quiet grief, now resonates louder than ever. His minimalism is a lesson in maximal empathy—an invitation to participate, to carry weight, to mourn collectively.

Today’s queer art doesn’t strive for inclusion—it declares inheritance. These artists aren’t entering institutions as novelties, but as heirs, archivists, and architects. They engage with the past not to repeat it but to re-edit it—rewriting the story with more names, more bodies, more possibilities.

Because the fight isn’t finished. Censorship flares, bigotry rebrands, policies backslide. And yet, queer art persists—scrawled in alleys, streamed across servers, whispered in movement. It remains the pulse beneath resistance: fierce, unfinished, and unforgettable.

Spaces of Visibility: LGBTQ+ Art Museums and Collections

Celebrating a Once-Marginalized Legacy

Clover Leary, Cassils in Tiresias (ca. 2013)

...

There was a time when LGBTQ+ art was relegated to the margins—confined to coded references, secret salons, or misattributed genius. Galleries dared not hang it; institutions erased its makers. Yet from those erasures, new sanctuaries have been carved: queer museums, archives, and collections that refuse forgetting, turning the overlooked into landmarks.

Foremost among them is the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in New York City. It stands as the first—and still only—state-recognized LGBTQIA+ art museum in New York. Born from the private collection of Charles Leslie and Fritz Lohman, the museum grew from intimate gatherings into a formidable archive of queer vision. Today it houses works spanning centuries and continents: baroque erotic etchings, defiant 1980s protest prints, contemporary nonbinary performance stills. Each exhibition not only showcases art but reframes history, asking: What were we never taught to see?

In Los Angeles, the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at USC has become the largest repository of queer personal histories in the United States. Shelved within its walls: love letters written under wartime blackout curtains, photos of 1970s drag queens stepping into daylight, minutes from organizing meetings once held under police surveillance. It does not only display—it protects, records, and remembers.

Across the Atlantic, Berlin’s Schwules Museum—established in 1985—was among the first of its kind. It curates exhibitions on queer German artists, movements, and histories, tracing a lineage disrupted by fascism and revived by defiance. Every exhibition echoes with ghosts made visible. In London, Queer Britain has opened its doors to visitors seeking stories lost in empire’s footnotes. Meanwhile, in San Francisco, the GLBT Historical Society & Museum continues to collect, display, and celebrate the local—and global—pulse of queer resistance.

These institutions do more than exhibit: they offer ritual space for grieving, celebration, contemplation, and protest. They are not mausoleums but living rooms of memory—intergenerational parlors where a new kind of art history is being rewritten in real time.

Adoption by Mainstream Institutions

The ripple has reached the center. Major museums—long complicit in exclusion—have begun to reckon with their omissions. At the Tate, the Queer Lives and Art initiative has reframed canonical works through a prism of queer identity: suddenly a marble youth is no longer neutered, a lingering hand no longer innocent. The British Museum offers an LGBTQ histories trail, drawing lines between ancient artifacts and modern visibility—proof that queerness predates categorization.

In California, the Palm Springs Art Museum’s Q+ Art initiative elevates contemporary queer voices, from installation art to digital performance. No longer hidden in back galleries, queer art now speaks from center stage, rewriting what the museum experience can mean. This is not tokenism—it is tectonic shift.

Mainstream adoption has its limits: curatorial oversight still favors palatable queerness; queer artists of color remain underrepresented. But the needle moves. The fact that these institutions even admit the necessity of queer narrative marks a fundamental cultural shift.

As more galleries trace queer lineages within their own walls, the once-sidelined becomes central. The museum evolves from gatekeeper to accomplice—from archive of taste to arsenal of truth.

The Enduring Legacy and Future of LGBTQ+ Art

Mickalene Thomas, Do What Makes You Satisfied (ca. 2006)

...

LGBTQ+ art is not a genre. It is a lineage, a constellation, a coded archive etched in ink, clay, blood, rhinestone, and rage. It stretches back thousands of years and stretches forward with no end in sight—a record not only of what queer artists have made, but of the worlds they’ve conjured, demanded, and refused.

From the cryptic homoeroticism etched onto ancient Moche pottery to the defiant installations of Cassils and Zanele Muholi, queer creativity has always moved in tandem with risk. Where empires criminalized love, queer artists recoded it. Where museums erased names, zines and murals remembered. The history of LGBTQ+ art is the history of survival by reinvention—of the brushstroke as subversion, the silhouette as sanctuary.

Some works whisper: a turned shoulder, a lavender hue, a mythic allegory. Others shout: a protest quilt the size of a city block, a public performance where the artist bleeds or weeps or roars. Whether cautious or confrontational, these gestures hold a common charge: a longing to be seen as one truly is—and to make that visibility undeniable.

The Harlem Renaissance showed how art could rewrite public identity through community. The AIDS crisis proved how art could weaponize grief into policy change. The Queercore movement taught that you don’t have to wait for acceptance when you can make your own stage, your own sound, your own myth. And now, in the 21st century, LGBTQ+ artists operate with an unprecedented multiplicity of tools—VR, AI, bodycam, drone, DNA—remapping intimacy, identity, and kinship in ways both expansive and intimate.

But the fight is far from over.

Even now, galleries and governments attempt to redact what queer artists reveal. In some countries, it is still illegal to depict queerness in public. In others, it is erased through subtler mechanisms: underfunding, exclusion from retrospectives, the quiet refusal to name queerness in wall text. Against these forces, artists continue to create—and in doing so, they resist not only repression, but erasure.

Museums like the Leslie-Lohman Museum and Queer Britain serve as bulwarks, preserving legacies once lost to silence. Meanwhile, major institutions recalibrate—slowly—integrating LGBTQ+ narratives into their collections. Even if the frameworks are imperfect, the shift is real. Queerness is no longer exiled to footnotes. It’s now folded into the central story: of modernism, of protest, of beauty, of form.

And still, the most radical thing a queer artist can do is make something in their own image.

Across continents, queer creators continue to layer their work with hope, fury, and radical imagination. They explore not just who they are, but who they might become—and who they refuse to be. They stitch visibility into the seams of culture. They refuse nostalgia that excludes and futurism that erases. They demand a world that does not just tolerate, but transforms.

If there is one unifying truth across this lineage, it’s that art is not simply reflection—it is construction. Queer art doesn’t just show us the world as it is. It dares us to imagine it otherwise.

Each drawing, performance, photo, poem, sculpture, or sonic rupture is a flare lit in the dark—proof that someone was here, someone loved, someone dreamed, someone fought. Together, they form a constellation too bright to be ignored.