The scent of camellias fills the air as one cracks open an original copy of “Yatsuo no Tsubaki”. Imagine yourself in mid-19th-century Japan, the Edo period (1603–1868) on the wane. The years between 1860 and 1869 unfold like a gentle hush before a storm—an era of relative internal peace yet undercurrents of societal upheaval swirl. And in these woodblock pages, Taguchi Tomoki captures this transitional moment with an unerring eye, preserving both the serenity of the waning Edo age and the whiff of modernity about to wash ashore.

Key Takeaways

- A Blossoming Odyssey: Taguchi Tomoki’s “Yatsuo no Tsubaki” immerses us in a lush realm of camellias, birds, and tidal waters—a place where traditional Japanese reverence for impermanence surfaces in every petal and wing.

- A Bridge Between Eras: Created between 1860 and 1869 at the twilight of the Edo period and the dawn of Meiji, these woodblock prints straddle two worlds, reflecting both the refined aesthetics of a feudal age and the emerging spark of modern transformation.

- Minimalist Grace: While other ukiyo-e giants dazzled with vibrant panoramas, Taguchi’s style stands apart for its muted hues, serene lines, and meticulously distilled forms—an ode to nature’s subtle grandeur.

- Everlasting Resonance: Despite scant biographical details, Taguchi’s timeless influence lingers. “Yatsuo no Tsubaki” continues to captivate scholars and decorators alike, reminding us that even in a bustling, globalized era, the stillness of nature endures.

The Enigmatic Figure: Who Was Taguchi Tomoki?

Taguchi Tomoki (田口智樹) is a name etched into the late 19th century, bridging that final Edo decade and the early Meiji years. His birthdate remains somewhat opaque, overshadowed by better-documented contemporaries like Katsushika Hokusai or Utagawa Hiroshige. Yet what is established is that Taguchi thrived in a pivotal era—a society pivoting from feudal isolation to Western-influenced modernity.

He specialized in nature prints, focusing on birds, plants, and the rolling ocean. Such a concentrated gaze suggests he found infinite wonder in the rhythms of flora and fauna. While much of ukiyo-e celebrated urban amusements, Taguchi chose to transfix the viewer with a quieter palette: serene lines, muted tones, and uncluttered compositions.

Art historians have wrestled with the scarcity of Taguchi’s biography. We know that, unlike the popular masters who marketed themselves aggressively or joined large schools, Taguchi’s circle was more intimate. Still, crucial facts endure: he produced “Yatsuo no Tsubaki” between 1860 and 1869, a nine-year feat that cements his stature as an artist of great subtlety and skill. With an extraordinarily modern eye—back then and to this day.

Minimalism Amid a Flourishing Genre

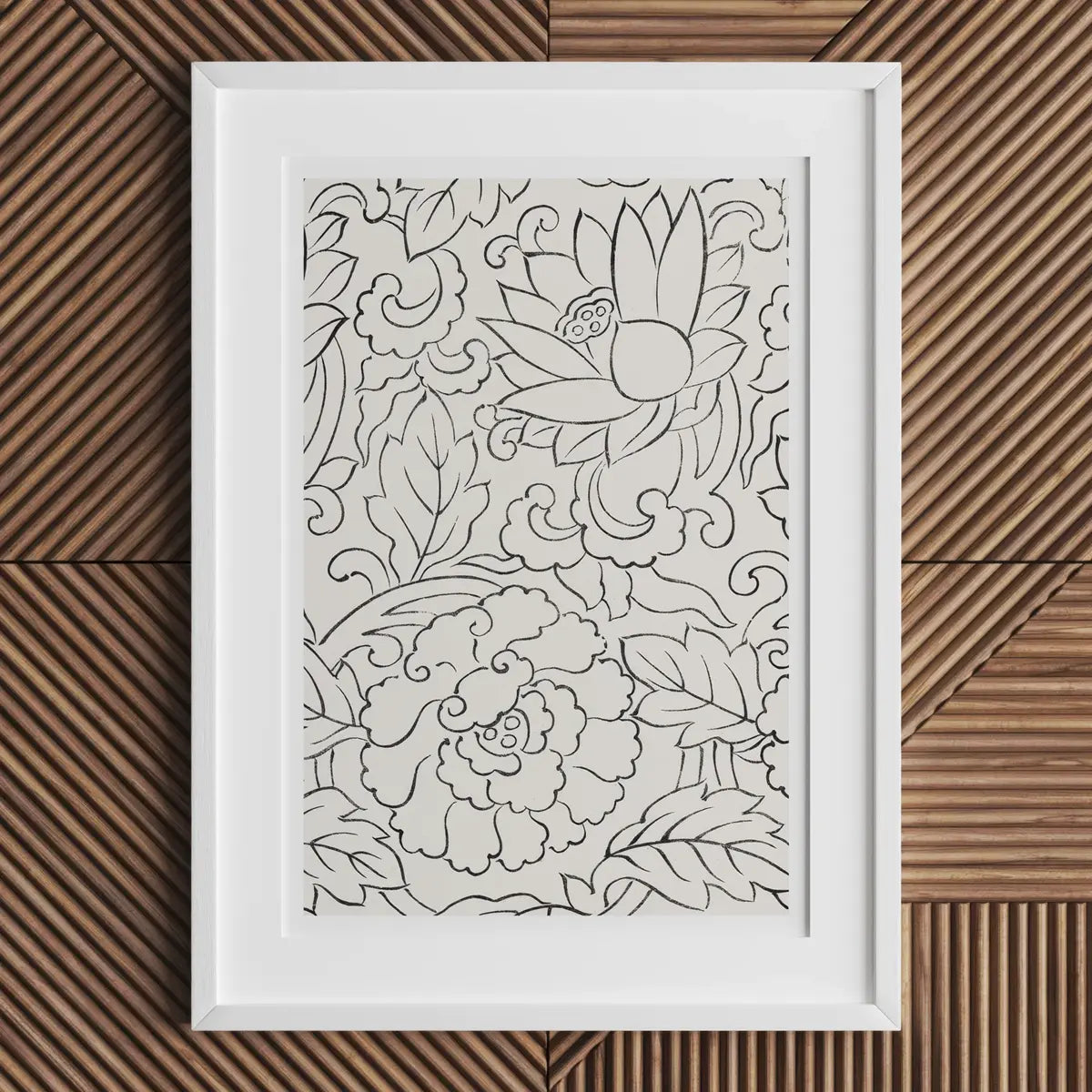

When you pick up a typical Edo print—vivid with courtesans’ flamboyant robes or Kabuki actors’ dramatic postures—you might be startled by Taguchi’s near-silent compositions. His works, as one critic described, reflect a “minimalist lens,” anchored by simple tones and delicate lines. Occasionally, you’ll see a solitary bird or a lone camellia blossom floating in negative space.

That restraint feels almost modern. Some speculate Taguchi foretold the aesthetic that would emerge strongly in the Meiji era, when Western influences mingled with Japanese traditions. Others read in his work a personal philosophy: a preference for the elemental, for subtle interplay between shape and negative space, akin to the bare quiet of a Zen garden.

Nature itself was the drama. There were no teeming cityscapes or courtesans crowding these frames. Just plants, birds, and the unfathomable hush of the ocean or sky. Some scholars see this as a reflection of the merchant class’s growing appreciation for a gentler side of life, while others believe Taguchi’s temperament simply leaned toward calm introspection.

A Flower in Focus: The Heart of “Yatsuo no Tsubaki”

At the center of this collection lies the camellia, or tsubaki, and from it the entire opus derives its name. The actual title—“Yatsuo no Tsubaki” (八丘椿)—has been variously translated: some read it as “Eight Hills Camellia,” others, “Ten Bamboos.” The single definitive certainty is the presence of 椿, the kanji for camellia.

During the Edo period, the camellia carried a bouquet of symbolic meanings: beauty, resilience, love, even spiritual endurance. One cannot ignore its link to kakure kirishitan (hidden Christians) who, persecuted under the Tokugawa shogunate, reportedly took solace in camellias blooming in secret enclaves. The flower’s bold red conveys inner strength—a quiet power blossoming despite the chill of winter.

Taguchi underscores this symbolism by depicting camellias in multiple contexts: sometimes solitary, sometimes entwined with other flora, and occasionally placed near birds that seem poised to drink in the flowers’ essence. Through repeated inclusion of this resilient bloom, the artist might be saluting Edo Japan’s capacity for perseverance, or even hinting at his society’s fragile transitions.

Layers of Symbolism: The Camellia as a Cultural Conduit

The camellia resonates far beyond mere aesthetics. In some Edo contexts, it signaled refinement and perfection. Blooming in colder months, it became an emblem of perseverance, a delicate reminder that life breaks forth even in adversity. For persecuted Christian communities hiding in rural enclaves, the abundant camellia was rumored to represent the Virgin Mary, or quiet faith itself.

Taguchi’s prints, thus, vibrate with layered meaning. A bright red tsubaki could hint at the pulsating heart of a changing Japan, or the hidden convictions of marginalized believers. His minimalist compositions highlight each flower’s silhouette, drawing the eye inward to see beyond petals into the swirling undercurrents of Japanese society in flux.

Birds and Blossoms: The Kachō-ga Tradition

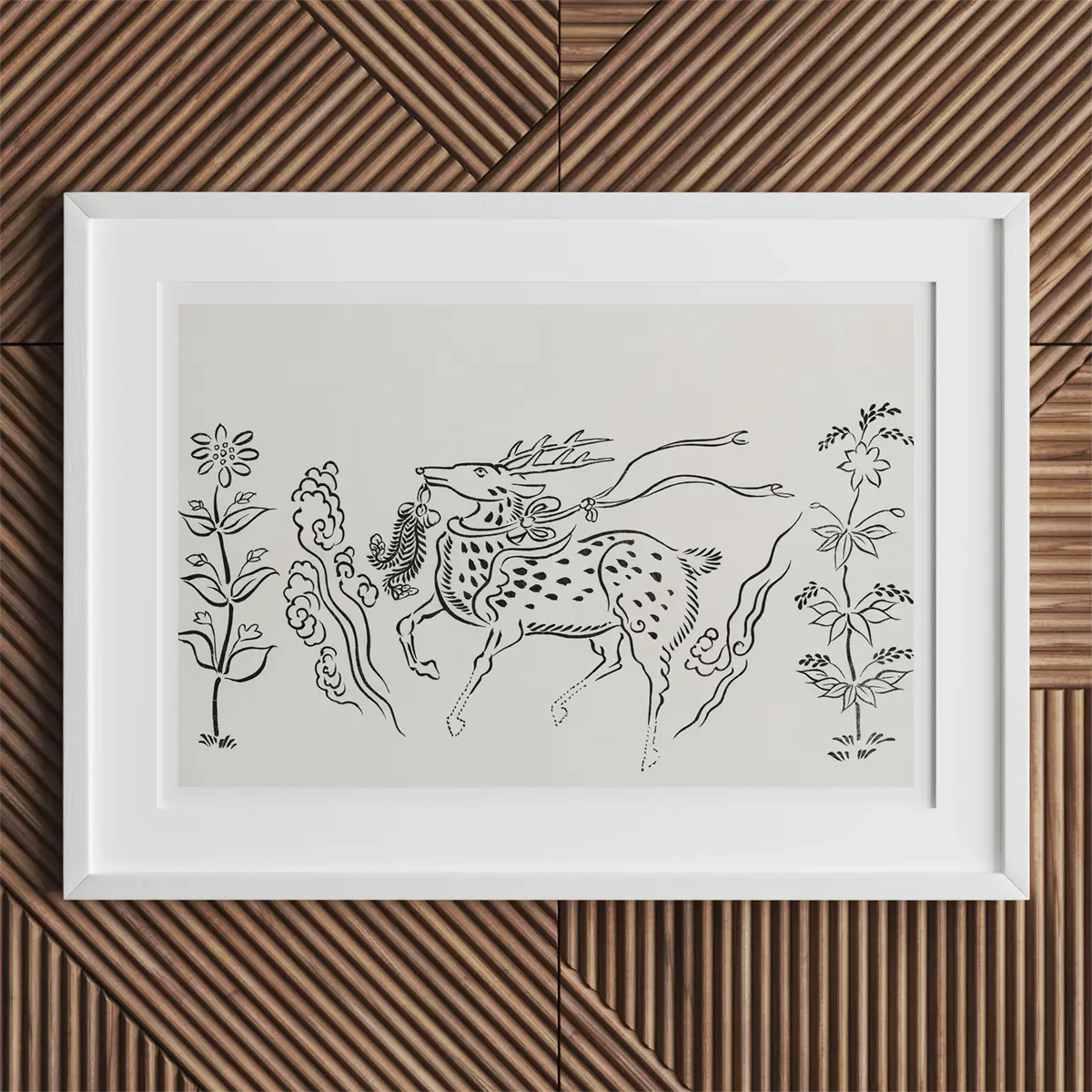

The tradition of kachō-ga (花鳥画), meaning “bird-and-flower painting,” has long flourished in Japan. In the Edo period, nature was never a mere backdrop but a lively protagonist carrying spiritual and aesthetic weight. Think of a mountain signifying divine grandeur, or a flowing river capturing time’s unstoppable current.

Taguchi’s contribution to kachō-ga focuses on the interplay of shape and negative space. Consider his depiction of swans: stark, elegant lines suggest ephemeral grace. Or the swirl of an ocean wave is rendered so simply that we feel the hush of the water itself. In some pieces, Taguchi introduced abstract fan shapes—rotating silhouettes on a limited palette—teasing a modern aesthetic afoot well before Japan’s formal embrace of Western artistry in Meiji.

Some images shimmer with vibrant reds or verdant greens, while others retreat into nearly monochromatic calm. This duality underscores Taguchi’s range. He can exalt the buoyant energy of a red camellia in bloom, or gently hush the print with slate-gray plumage on a crane. In every instance, delicate linework stands out as a hallmark of his style, demanding as much attention as the color itself.

Ornamental Eye: Turning Nature into Decorative Motifs

Taguchi’s skill lay in transforming the natural into the ornamental. A swoop of a heron’s neck might be stylized into a looping curve reminiscent of a calligraphic brushstroke. A cluster of camellias could be arranged in a swirl that mirrors the radial symmetry of a fan, forging a delightful interplay of geometry and organic forms.

Ornamental design was not a trivial pursuit. In a culture that placed high value on synergy between daily life and beauty—where even a tea bowl was crafted with mindful elegance—Taguchi’s motifs found broad resonance. They slipped effortlessly into screens, textiles, and ceramics. Ultimately, “Yatsuo no Tsubaki” stands as a testament not merely to natural observation, but to the unbreakable link between art and daily life.

Cultural Bridges

Shadows of Edo: A Time of Peace and Flourishing Art

Few centuries in Japanese history stand as vibrantly as the Edo period, beginning in 1603. By the mid-19th century, roughly when Taguchi Tomoki was honing his craft, the Tokugawa shogunate still held sway. Yet beneath that seemingly rigid social structure, the merchant class (chōnin) had accumulated considerable economic power—despite being in the officially lower social tier.

Artists seized that moment. The wealthy merchants coveted prints that captured the ephemeral delights of urban life: theater nights, courtesans, kabuki actors, seasonal festivals. In this cultural crucible emerged ukiyo-e, the “pictures of the floating world,” which initially served as novel illustrations and later blossomed into standalone art. These prints, sold at the price of a simple bowl of noodles, catered to everyday people as well as connoisseurs.

Such was the floating world ethos: capturing transient pleasures, reveling in life’s fleeting nature. The classical Buddhist notion of ukiyo, or impermanence, had mutated into a concept that celebrated the very ephemeral joys it once cautioned against. By the 1860s, ukiyo-e soared as the dominant art form, depicting everything from ravishing bijinga (images of beautiful women) to sprawling landscapes.

Edo’s Nature Fetish and the Imprint on Society

Japan’s Edo society revered nature in ways that extended to garden design, poetry (haiku), and seasonal festivals. One might witness city dwellers thronging to the countryside to watch cherry blossoms or autumn maples in a tradition that endures to this day. The ephemeral bloom of sakura or the crisp winter blossoming of camellia served as a humbling reminder of time’s passage.

Artists like Taguchi harnessed this reverence for personal and communal expression. A delicate branch of plum blossoms, a crane rising skyward—each rendered meticulously in woodblock form—became a mirror reflecting Edo values. Meanwhile, the merchant class, flush with wealth, sought such prints for both beauty and the symbolic prestige they conferred.

Though the Meiji Restoration would usher in railways, Western suits, and industrial factories, Taguchi’s calm depictions in “Yatsuo no Tsubaki” remain anchored in the older world’s aesthetics. Yet they also herald a new age, bridging the rustic hush of Edo with glimmers of modern, minimalist design—perhaps an early whisper of changes to come in Japanese art.

Mujo and the Celebration of Ephemerality

Why did the Edo populace so adore nature prints? Mujo (無常), the Buddhist recognition that nothing endures, might be the cornerstone. A cherry blossom, vanishing in days, taught humility and awareness of life’s brevity. A camellia, blossoming in winter, symbolized the unstoppable cycle of rebirth.

In Edo city life—abuzz with commerce, performance, and fleeting amusements—prints like Taguchi’s kachō-ga offered spiritual refreshment. You might not visit a quiet pond or mountain daily, but a single print on your wall could transport your mind there. The merchant class, growing wealthy yet still nominally “low” in social status, found in nature prints a subtle statement of cultivated taste and philosophical depth.

Transition to Meiji: Carrying Tradition into a New Dawn

By the time 1868 arrived, the Tokugawa shogunate had collapsed. The Meiji Restoration introduced Western attire, industrial reforms, and a thirst for modernization. Samurais traded swords for government posts, and Japanese society convulsed with possibilities. It is precisely this era that frames Taguchi’s creation of “Yatsuo no Tsubaki” (1860–1869).

When we hold a Taguchi print, we are physically touching the tension of two worlds. The prints reflect Edo’s love of understated beauty yet nod toward new aesthetic directions. Minimalism, a hallmark we associate with modern Japanese design, is already present in Taguchi’s subtle lines and subdued backgrounds. In that sense, “Yatsuo no Tsubaki” is not just an homage to Edo but an early seed of modern Japanese artistic identity.

Then and Now: Cherished Treasure to Global Renaissance

In Edo society, the immediate popularity of “Yatsuo no Tsubaki” can be inferred from how it circulated among collectors. Sadly, few contemporary reviews survive. Yet the prints’ presence in “pattern references” for other crafts—like Inuyama ware—suggests they were valued beyond mere household decoration. Owners cherished these volumes, passing them down or trading them among fellow enthusiasts.

Centuries later, Taguchi’s legacy persists. Museums, galleries, and private collectors keep these prints in stable climates, away from humidity or overexposure to light. Enthusiasts scour auctions for rare first editions, while new admirers discover his artistry through online shops selling reprints on canvas or archival paper. The modern interior design world, with its appetite for subtle patterns, has embraced Taguchi’s minimalism—his birds and blossoms reimagined in large-scale wall art or even textiles.

Pages of Beauty

“Yatsuo no Tsubaki” was originally published as a book of prints. The earliest known edition came out between 1860 and 1869, just before Edo yielded to the Meiji era in 1868. Though the name of the publisher remains unclear, it’s known that subsequent versions materialized—Yūrindō in Tokyo released an edition around 1900, extending the legacy of these images far beyond the strictly “Edo” timeframe.

Inside those pages, ornamental designs mingle with nature scenes in a dance of swirling lines and subtle color. One record places the book among pattern references used in making Inuyama ware, a style of ceramic. This suggests Taguchi’s motifs enjoyed a life beyond strictly “fine art,” influencing artisans who rendered camellias or birds in glaze and clay.

What began as an Edo-era volume soon found new audiences, particularly once it was digitally preserved by the Getty Research Institute. With the modern rise of online art marketplaces, Taguchi’s prints have resurfaced as giclée reproductions, beloved by collectors craving that same quiet hush of minimalism in their own living rooms.

Editions and Reprints Through the Ages

By the early 1900s, Yūrindō took over the publication mantle, reflecting a renewed appreciation for Edo culture that often swept Japan during the late Meiji and Taishō years. In the West, Japan’s “opening” had fueled a mania for all things Japanese—kimono, screens, ukiyo-e prints. Collectors like Ernest Fenollosa and institutions like the Getty soon sought to archive and display these treasures.

That the Getty Research Institute has digitized “Yatsuo no Tsubaki” stands as a testament to the collection’s ongoing relevance. It is no longer confined to a physical library in Tokyo or a private collector’s shelf; now a global audience can marvel at Taguchi’s devotion to fleeting nature. Meanwhile, modern entrepreneurs turn Taguchi’s designs into phone cases or café posters, bridging centuries at the click of a mouse.

The Camellia Persists

Like a camellia surviving the frost, “Yatsuo no Tsubaki” endures. In those pages, we witness the fruit of a pivotal nine-year labor (1860–1869), bridging the past and future of Japanese art. Freed of superfluous detail, each print breathes with quiet synergy—nature turned into profound design, simplicity echoing in an era often overshadowed by grander or more flamboyant works.

Taguchi’s “Yatsuo no Tsubaki” occupies a liminal space: historically Edo, but edging into Meiji. Its minimal lines and subtle shading predict the broader aesthetic shifts that would come to define modern Japanese design, from wabi-sabi teahouses to contemporary minimalism.

As we unravel the symbolism—the steadfast camellia, the fleeting swan, the unstoppable flow of the river—we sense Taguchi’s commentary on a Japan about to shed its centuries-old isolation. Each woodblock reveals an artist determined to preserve the quiet reflection of his homeland’s natural wonders, even as the clang of modernization approached.

What started as an homage to nature’s beauty became an historical artifact, capturing the sense of calm and reflection that Edo culture cherished. Yet it also sowed seeds for a modern minimalism that Japan would later share with the world. For historians, “Yatsuo no Tsubaki” is a treasure trove of Edo craftsmanship and a reflection of political and cultural shifts. For the casual viewer, it’s simply a wondrous breath of fresh air—a testament that complexity can dwell in the simplest lines.

In an age teeming with digital noise and constant flux, Taguchi’s lines encourage us to pause, to notice the slender arc of a petal or the grace of a bird suspended mid-flight. The result is a narrative that lingers—a floating world of nature still afloat after all these years.