The cobalt coils and golden crescendos of The Starry Night beckon us into Vincent van Gogh’s restless cosmos, where turbulence and transcendence converge with breathtaking fervor. In those spiraling constellations, we glimpse both the eloquent depth of his inner life and an enduring echo of the human spirit’s own search for solace amid chaos.

Few figures in Western art have fused profound technical daring with such raw emotional honesty. Indeed, Van Gogh’s short, impassioned life—from the obscurity of his early years to the staggering posthumous fame that crowned him—remains a testament to the paradox of brilliance born from hardship.

So how did this unassuming Dutchman, scarcely recognized during his own lifetime, rise to such global renown? The answer lies in the interplay of radiant color and haunting darkness, a tension that shaped both his daily existence and the artworks that now illuminate galleries around the world.

Key Takeaways

- A Blossoming from Shadow: Van Gogh’s unyielding empathy and quest for spiritual purpose infused his earliest canvases with a somber sincerity, reflecting both a reverence for rural life and a determination to find the sacred in the ordinary.

- Metamorphosis in Paris: Immersed in the avant-garde currents of Impressionism and Japanese Ukiyo-e, he ignited his once-muted palette and embraced a bolder, more emotive style—a transformation that would shape his celebrated post-Impressionist vision.

- Arles: The Furnace of Creation: In the southern sun, Vincent’s burning passion yielded the Yellow House dream, culminating in a breathtaking torrent of works like the vivid Sunflowers. The tempestuous friendship with Paul Gauguin lit a fuse that exploded into the tragic, iconic “ear incident,” yet fueled his fiercely original artistry.

- Art as Refuge in Saint-Rémy: Confined by mental torment, he painted his way to fleeting serenity. Works like The Starry Night transformed raw inner chaos into cosmic poetry, proving that his art remained a beacon, even as his psyche wavered.

- A Legacy of Unending Luminescence: Despite his untimely death, Van Gogh’s revolutionary brushwork, daring color juxtapositions, and heartfelt humanity continue to mesmerize and inspire, standing as a testament to the eternal fusion of vulnerability and genius.

In Search of the Sacred in the Everyday

Childhood Shadows and Early Sparks

![]()

Vincent Willem van Gogh arrived on March 30, 1853, in the village of Zundert, nestled amid the quiet fields of the Netherlands. From his father, Theodorus—an austere minister—Vincent absorbed a sense of religious devotion, though faith would wear many guises throughout his life. A sorrowful prelude colored his entry into the world: his parents had lost a stillborn son, also named Vincent, just one year prior. That quiet heartbreak seemed to cast a subtle pall over his childhood, shaping the reflective sensitivities that would later feed into his art.

From his earliest days, he shared a powerful bond with his younger brother, Theo, whose presence would prove unwavering. By 1872, they began a lifelong correspondence that now provides an intimate lens into Vincent’s inner workings: the flickering doubts, the soaring hopes, and the sometimes contradictory fervor fueling every brushstroke. Before art claimed him, Van Gogh meandered along varied paths—he was an art dealer for Goupil & Cie (owned by his uncle), a teacher, a bookseller, and even a lay preacher in the Borinage mining region of Belgium. His attempts to minister to impoverished communities reflect a deeply rooted compassion, though his overt piety did not bind a stable congregation. When the church abandoned him, he turned to a more personal form of evangelism: drawing, encouraged by Theo’s unwavering faith and financial support.

Even in these nascent experiments, Van Gogh exhibited a keen empathy for common folk, revealing a germ of what he admired in the “peasant painters” he studied. He was profoundly moved by Jean-François Millet, whose earthy portrayals of farm laborers inspired Van Gogh to dig beneath the surface of everyday toil. In this early phase, Van Gogh’s palette was subdued, dominated by dark, sober hues, capturing the austere dignity of rural life. But even within those muted tones, one sensed a flicker of his desire to mine the divine from the ordinary.

The Dutch Period—Sowing Seeds in Earthy Tones

![]()

Between 1881 and 1885, Vincent honed his artistic purpose in what is often termed his Dutch period. Returned to his parents’ home in Etten, he devoted himself to drawing and outdoor studies, capturing local landscapes with a painstaking devotion to peasant life. Yet domestic life in Etten weighed heavily. Relatives viewed his calling with skepticism, wary of the precarious existence of an artist.

Personal travails soon joined the fray: Vincent’s infatuation with his widowed cousin Kee Vos was rebuffed, a familial rift that prompted his departure in December 1881. Later in The Hague, he met Sien Hoornik, whose background scandalized Vincent’s peers and family—she had a young daughter, bore complex hardships, and represented a dimension of society typically shunned. Yet Van Gogh’s stubborn empathy compelled him to stand by her. In sharing a rented studio, he glimpsed firsthand the stark struggles of the marginalized.

Simultaneously, Anton Mauve, a relative by marriage, provided technical instruction, guiding him through the disciplines of watercolor, oil painting, and perspective. Those formal lessons fused with Vincent’s own observations of laborers in the fields, culminating in The Potato Eaters (1885), his first major canvas. In this dimly lit portrait of a peasant family at meager supper, Van Gogh’s brushwork is rugged, and his colors are earthy and raw, mirroring both the physical toil of his subjects and the weight of his own moral convictions. Additional “peasant character studies” from that time further underscore his belief in the dignity of life on society’s fringes. These images, rendered in darkness, stand in profound contrast to the radiant style that would soon erupt when Van Gogh encountered the vibrant palette of more modern movements.

Chrysalis in the City of Light

Paris—A Labyrinth of Inspiration

![]()

In 1886, Van Gogh arrived in Paris to join Theo, now working as an art gallery manager. The city pulsed with artistic revolution: Impressionists were deconstructing light itself, while Neo-Impressionists meticulously placed dots of pigment to conjure shimmering illusions. Vincent plunged into this creative maelstrom, observing Monet, Degas, Seurat, and Signac with wide-eyed wonder. In response, he brightened his once-dreary palette and experimented with looser brushwork, adopting elements of Pointillism to investigate color relationships and optical effects.

Yet Van Gogh’s influences weren’t confined to local painters. An exhibit of Japanese Ukiyo-e prints ignited him, with their flattened perspectives, bold outlines, and luminous planes of color. He collected these prints obsessively, even organizing a Japanese print exhibition in 1887, hoping to share his discovery with fellow avant-garde minds. His circle grew beyond the established Impressionists, drawing in younger radicals such as Émile Bernard and Paul Gauguin. Montmartre’s bustling cafés served as lively forums where passionate debates raged about the future of art. In a city of shifting alliances, Van Gogh absorbed every spark, forging a style both informed by others yet defiantly his own.

As he stood before the kaleidoscopic works of the Impressionist vanguard and immersed himself in the lyrical minimalism of Japanese prints, Van Gogh found new confidence in color’s power to express emotion. This cross-pollination of styles awakened him to the poetics of the brushstroke and the limitless possibilities of hue. Old gloom gave way to a blazing palette. Though his relationships—both artistic and familial—were seldom straightforward, those fraught alliances in Paris catalyzed his transformation into a fully realized post-Impressionist.

Southern Light, Southern Longings

Arles—The Vision of a Yellow House

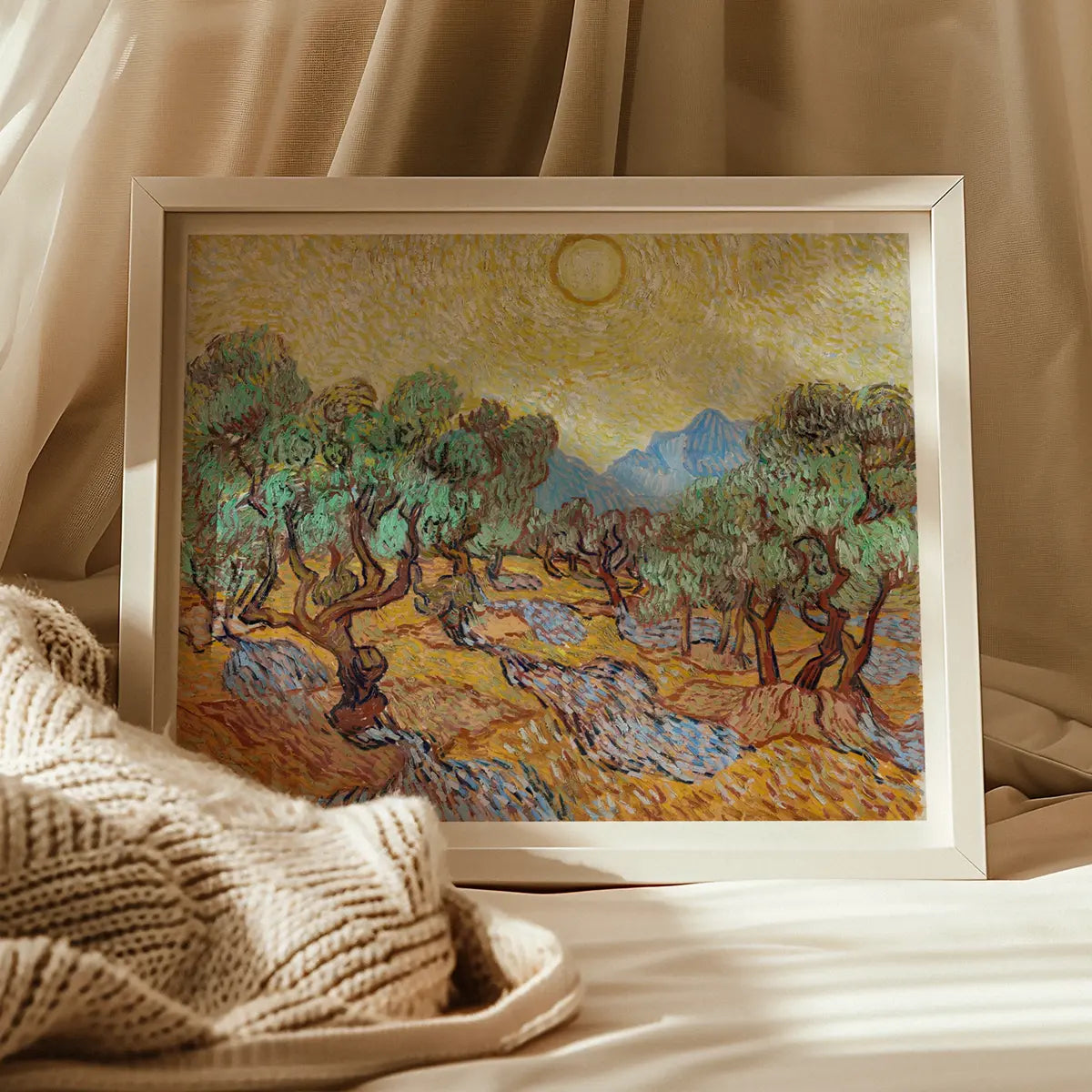

Longing for sun-drenched skies and respite from city life, Van Gogh relocated in February 1888 to Arles, in the Provence region. There, in the modest abode he christened the “Yellow House,” he entertained dreams of an artistic commune, a sanctuary for fellow painters who would share ideas and create in harmony under the southern sun.

The Provençal landscape enfolded him with colors at once brilliant and subtle: copper-hued wheat fields, stunted olive trees shimmering in the glare, and peach blossoms blush-pink against a sky of near-lavender. For Van Gogh, the South held a luminosity he deemed akin to Japan’s—a place where nature and art converged in a spiritual symphony. Here he embarked on his now-famous sunflower series, saturating the canvas with yellows that burned like torchlight, a palette symbolic of warmth, gratitude, and the brightness of camaraderie.

He envisioned sharing these radiant scenes with Paul Gauguin, who arrived in October 1888 to help realize Vincent’s utopian dream. But the kinship soured swiftly. Gauguin preached the merits of imagination over direct observation, while Van Gogh clung to the immediacy of painting en plein air. Tempers flared in that small house, culminating in the infamous “ear incident” in December 1888, a tragic and violent manifestation of Van Gogh’s mounting mental strain. Gauguin departed soon after, leaving Vincent both crestfallen and creatively charged. In Arles, he produced a staggering array of masterpieces—including Café Terrace at Night, The Bedroom, and Starry Night Over the Rhône—each bearing the raw imprint of emotional tension and a fiercely personal color scheme. That chapter in the Yellow House underscores how beauty and heartbreak were, for him, interwoven threads of the same tapestry.

Saint-Rémy—Confined Yet Unbroken

![]()

In the wake of mental breakdowns, Van Gogh voluntarily checked himself into the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy in May 1889. For a full year, he moved through cycles of crisis and relative calm, oscillating between delusions and periods of intense productivity. The asylum’s monastic hush coexisted with the swirling anxieties in his mind.

Remarkably, he continued painting, often from the asylum garden, capturing wheat fields glimpsed through barred windows, and even sketching fellow patients. A separate room became his studio, where art served as both anchor and outlet, a slender but potent lifeline in times of deep emotional disarray. The result was a trove of works reflecting both hope and upheaval. Perhaps none is more iconic than The Starry Night, a cosmic tapestry of roiling cerulean and luminous orbs—a glimpse, perhaps, into the vortex of Van Gogh’s psyche.

The cycle of torment sometimes led to bizarre incidents—eating oil paint during a delirium—yet in moments of relative stability, he worked with near feverish dedication. He created pieces such as Irises, Wheatfield with Cypresses, and the tenderly optimistic Almond Blossom, painted in celebration of his newborn nephew. These canvases attest to an extraordinary resilience: even as hallucinations, fears, and dread threatened to consume him, he harnessed that energy into color, shape, and line, forging art that vibrates with humanity’s fragile equilibrium.

Unraveling the Myth—Mental Health and the Artist’s Burden

So often, Van Gogh is enshrined as the quintessential “tortured artist,” tormented by madness. While records suggest he suffered from possible temporal lobe epilepsy, bipolar disorder, or other conditions (compounded by absinthe consumption and potential lead poisoning from paint), we cannot retroactively assign a single, neat diagnosis. Still, his letters recount chilling episodes of seizures, hallucinations, nightmares, and the infamous act of mutilating his ear in a moment of crisis.

Painting was more than a livelihood: it served as an emotional balm and a stabilizing force that tethered him to the tangible world. Some have too casually linked Van Gogh’s genius solely to his mental anguish, but that narrative oversimplifies. His greatness also emerged from rigorous study, a thoughtful grasp of color theory, and an unyielding work ethic. For Van Gogh, mental illness was an unfortunate reality—one he recognized, sought to cure, and fought against. His tragedy was real, but so too were the discipline, insight, and conscious craft that shaped his groundbreaking oeuvre.

Final Crescendo and Aftermath

Auvers-sur-Oise—A Day for Each Canvas

![]()

By May 1890, worn from the confines of the asylum, Van Gogh moved to Auvers-sur-Oise under the watchful care of Dr. Paul Gachet, a homeopathic physician with an artist’s sensibility. Nearer to Theo, Vincent found a setting both tranquil and creatively fertile. In a mere two months, he produced work at a staggering rate—almost one painting per day.

Though Dr. Gachet offered medical attention and personal sympathy, Van Gogh remained beset by anxieties: financial strain, fears of burdening Theo, and an unshakable restlessness of spirit. On July 27, 1890, in a field he had so often rendered in paint, he shot himself. He lingered two days, passing away at 37, leaving behind a body of art so potent it would reshape the trajectory of modern painting.

Among his late canvases, Wheatfield with Crows roils with tension, its obsidian birds cutting across a storm-darkened sky. The twisted roots in Tree Roots offer a tangle of earthly finality, while Portrait of Dr. Gachet captures a physician whose gaze reflects compassion tinged with sorrow. Vincent’s heart, so full of color and conflict, finally succumbed to the burden of his despair. And yet, in those last works, he imparted an enduring sorrow and grandeur that would outlive him.

The Canvas Beyond the Man

Post-Impressionist Vanguard—Van Gogh’s Defining Brushstrokes

Van Gogh’s style is often labeled Post-Impressionist, a moniker capturing the restless yearning of artists who pushed beyond Impressionism’s naturalism toward unfiltered emotional articulation. In Vincent’s case, color was both signifier and symbol—he used red and green, yellow and purple, blue and orange in tension to heighten visual drama and reflect emotive truths, rather than mere photographic representation.

His hallmark impasto technique—where thick layers of paint stand boldly on the canvas—lends a tactile vibrancy to each swirl and slash of the brush. This approach reveals his emotional weather in every stroke, an unveiling of the man within the paint. Moreover, his fascination with Japanese prints (Ukiyo-e) played out in flattened perspectives, bold outlines, and sometimes unexpected angles, all feeding his appetite for experimentation.

Underpinning these aesthetic choices was a deep personal symbolism. Sunflowers signified gratitude and hope, cypresses evoked spiritual yearning, and swirling night skies hinted at the cosmic interplay of inner chaos and celestial grace. By wedding symbolic color to physical gesture, Van Gogh redefined how one could use a canvas to lay bare the soul.

Influence: The Pulse of Modern and Contemporary Art

The reverberations of Van Gogh’s style across 20th-century art are impossible to overstate. With his provocative color juxtapositions and emotive brushwork, he became a lodestar for the Expressionists and Fauvists alike. Henri Matisse and André Derain revered his willingness to defy the constraints of natural color. Meanwhile, Expressionists like Edvard Munch and Egon Schiele harnessed comparable emotional rawness, forging images that probe existential angst—an approach Van Gogh helped pioneer.

Artists in subsequent decades—from Willem de Kooning to Francis Bacon—credited Van Gogh as a formative spark, drawn to the unvarnished honesty and palpable energy in his images. Today, one still finds a lineage connecting Van Gogh’s legacy of subjective representation to contemporary art that breaks barriers in color usage, form distortion, and deeply personal storytelling. He not only questioned Western art’s established norms—he cracked them open, making room for infinite variations of artistic authenticity.

Cultural Icon—The Immortality of Vincent van Gogh

![]()

More than a century after his untimely passing, Vincent van Gogh’s brushstrokes continue to stir hearts, bridging solitude and solidarity in a single sweep of paint. His spiral galaxies remind us that chaos can yield transcendent beauty, his fields of wheat affirm a world grounded in earthy vigor, and his sunflowers glow with an undying warmth. Through every twist of color, we sense a man who wrestled mightily with life yet refused to forsake its astonishing wonder.

During his brief life, recognition eluded him. Yet in the century following his death, Vincent van Gogh has achieved a mythic resonance that rivals any artist in modern history. Prices for his works—now some of the most expensive ever sold—soar in part because collectors sense the gravitas of his story: the quiet luminescence of an unacknowledged genius, misunderstood in his own era but revered beyond measure today.

In Amsterdam, the Van Gogh Museum safeguards the largest trove of his paintings, drawings, and letters, welcoming millions of visitors each year. Here, one can follow the trajectory from dark early sketches to the riotous color of Provence, all the while hearing Van Gogh’s own voice in the letters he wrote so passionately to Theo. Beyond the museum walls, his images infiltrate every corner of popular culture—printed on postcards, reproduced in films, dissected in art schools, and glimmering in immersive digital displays worldwide.

Such universal appeal stems from a harmonious collision of factors: the exhilaration of his color palette, the human drama of his biography, and the tireless efforts of champions like his sister-in-law, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, who promoted his work posthumously. While the romantic notion of the “tormented genius” can be reductive, there is undeniably something about his fusion of suffering, empathy, and blazing innovation that resonates across time. It is that unresolved chord—struck between adversity and triumph—that enthralls us even now.

Van Gogh’s legacy is neither defined by the illness that haunted him nor by the despair that ended his life. Instead, it is the fire of his artistic quest—a flame stoked by humility, compassion, and a relentless curiosity—that endures. In his canvases, the human pulse beats, reminding us how deeply art can express both our afflictions and our aspirations. And so, the luminous tapestry he created remains—like a flickering lantern guiding us through the nights of our own doubt—forever illuminating, forever speaking the language of color and longing that transcends time.

Reading List

- Bailey, Martin. Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Mysterious Dr. Gachet. London: Frances Lincoln, 2021.

- Dekkers, Adriaan. Van Gogh’s Sunflowers Illuminated: Art and Science. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2014.

- Gayford, Martin. The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Arles. New York: Penguin Press, 2006.

- Hendriks, Ella, and Louis van Tilborgh. Vincent van Gogh: Paintings, Volume 2: Antwerp & Paris, 1885-1888. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2011.

- Jansen, Leo, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker, eds. Vincent van Gogh—Letters: The Complete Illustrated and Annotated Edition. London: Thames & Hudson, 2009.

- Jones, Jonathan. “Van Gogh: A Life in Letters.” The Guardian, June 12, 2009.

- Naifeh, Steven, and Gregory White Smith. Van Gogh: The Life. New York: Random House, 2011.

- Pickvance, Ronald. Van Gogh in Arles. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1984.

- Saltzman, Cynthia. Portrait of Dr. Gachet: The Story of a Van Gogh Masterpiece. New York: Viking, 1998.

- Schaefer, Iris, and Anna-Carola Krausse. Vincent van Gogh: The Complete Paintings. Cologne: Taschen, 2018.

- Soth, Michael. Van Gogh’s Last Dream: Auvers-sur-Oise July 27, 1890. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2001.

- Stone, Irving. Lust for Life. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1934.

- Thomson, Belinda. Van Gogh: Artist of His Time. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1981.

- Tilborgh, Louis van, and Teio Meedendorp. Vincent van Gogh: Paintings, Volume 1: Dutch Period 1881-1885. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2006.

- Van der Wolk, Johannes. Vincent van Gogh: Drawings. Zwolle: Waanders, 1990.

- Welsh-Ovcharov, Bogomila. Van Gogh in Perspective. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1974.

- Wilkie, Kenneth. Vision & Violence. Springdale, AR: Siloam Press, 2004.

- Zemel, Carol. Van Gogh’s Progress: Utopia, Modernity, and Late-Nineteenth-Century Art. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.