Vienna in the earliest years of the 20th century was a cauldron of ideas, a place where the aging glow of the Habsburg Empire mixed with the electric hum of modern thought. There, along the winding boulevards and in the smoky cafés, the ancient and the emerging seemed locked in a permanent waltz, generating a distinct artistic tension. Rich with philosophical debates, rebellious salons, and roving musicians, the city inhaled the old-world monarchic tradition and exhaled bold new sounds and visions.

For the Vienna Secession, formed in the late 19th century, everything hinged on reclaiming art’s freedom from the strangling constraints of stale tradition. They championed the motto, “To every age its art, to art its freedom,” an emblem of their unapologetic desire to break from the past. To them, it was not enough to replicate historical forms; art had to challenge, intrigue, and evolve. Nearby, the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshops) took these philosophies into the realm of practical design, fusing elegance and functionality into objects of everyday life. In such fertile soil of collaboration—where the borders of architecture, painting, furniture, and graphic design blurred—an extraordinary figure named Moriz Jung began to take shape.

Jung’s life unfurled with melodic brevity, like a violin concerto that raises goosebumps in its final notes, only to end sooner than anyone expects. Born in 1885 (in what was then Nikolsburg, Moravia, now Mikulov in the Czech Republic), he would soon migrate to Vienna’s thrumming center. There, soaking up the vitality of progressive schools and hearing the chatty swirl of café gossip, he found a stage unlike any other. Although the stage was set for his triumph, looming in the shadows was the specter of war, prepared to curtail his brilliance. But before history took that tragic turn, Jung’s art soared, a testament to his wit, his skill, and his unmistakable sense of humor.

Key Takeaways

-

A City on the Brink of Reinvention: Turn-of-the-century Vienna stood at an uneasy crossroads, where the old imperial tapestry was threaded with modernist daring, and where young visionaries such as Moriz Jung answered the rallying cry of the Vienna Secession with avant-garde fervor.

-

Postcards as Avant-Garde Canvases: Jung’s bold, often whimsical Wiener Werkstätte postcards redefined an everyday keepsake into a mini-gallery of satire, social critique, and slyly observed vignettes—allowing his mischievous creativity to travel far beyond the rarefied confines of traditional art circles.

-

Satire’s Subtle Sting: Beneath the brilliant colors and thick-lined humor lay an earnest commentary on the era’s churning anxieties—from the nervy flirtation with early aviation to Vienna’s smoke-filled cafés—revealing how laughter can cut as keenly as the sharpest blade.

-

A Career Shattered by War: Just as his star soared, the thunder of World War I conscripted Jung away from his brushes, thrusting him onto the brutal Carpathian front. His life ended at 29, leaving Vienna’s art scene to mourn a vivid, unfulfilled trajectory that had only just taken flight.

-

A Legacy That Refuses to Dim: Preserved in museum collections and hailed by scholars, Jung’s postcard masterpieces, satirical sketches, and deft illustrations still captivate modern audiences. His name echoes as a symbol of how wit, craft, and sheer inventive brilliance can outlast even the harshest of historical storms.

Moravian Roots and the Imperial Magnet

A Town Called Nikolsburg

1885: In the cobblestone quiet of Nikolsburg, Moravia, Moriz Jung entered a world of shifting imperial lines. This region—part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire—was known for its mosaic of ethnicities, languages, and layered traditions. One imagines a young Jung wandering those winding lanes, absorbing the unique local interplay of German, Czech, and Jewish heritages. At a distance, the resonant swirl of empire beckoned him toward the bejeweled capital.

Fateful Journey to Vienna

His arrival in Vienna was not a mere geographic shift; it was a leap into a city perched on the edge of transformation. Beginning in 1901, Jung enrolled at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Arts), immersing himself there until 1908. In these halls, he encountered Carl Otto Czeschka, Bertold Löffler, Felician Myrbach, and Alfred Roller, each luminaries tied to the Secession’s modernist pulse. Under their tutelage, Jung’s gift for illustration, printmaking, and a modern sense of composition blossomed.

Innovation and rigor defined the Kunstgewerbeschule: weaving, metalwork, painting—all these crafts interlaced. Yet it was in the intaglio and relief disciplines that Jung found a raw synergy between concept and craft. Whether shaping linocuts or conjuring lyrical woodcuts, he honed techniques that would soon make him a recognizable name. By 1906, while still juggling student life, he published Freunde geschnitten und gedruckt von Moriz Jung (Friends Cut and Printed by Moriz Jung), focusing on animal imagery. The book exposed his budding fascination with natural forms—a theme resonant with the Art Nouveau swirl of the time.

Rising Above the Schoolroom

In 1907, while not yet finished with his formal studies, Jung received a prestigious commission from the Wiener Werkstätte to design the poster for the newly opened Cabaret Fledermaus. The cabaret itself was a cultural hotspot, and that a student from the Kunstgewerbeschule garnered such trust spoke volumes about his creative brilliance. The same year, he began contributing to the Wiener Werkstätte’s postcard series, setting off an impressive run where he would craft approximately 63 designs—many of which survive as key reflections of Viennese humor and style.

Why did these achievements stack up so quickly for him? Perhaps it was the ferment of the capital city. Perhaps it was the mentorship of teachers devoted to modernist ideals. Or perhaps it was Jung’s own drive, a restlessness that manifested in delicate lines and whimsical colors. By the time 1907 turned to 1908, Jung had established himself as a promising voice in a crowded chorus of Viennese innovators.

Key Dates from the Formative Years

1885: Birth in Nikolsburg, Moravia

1901–1908: Studies at the Kunstgewerbeschule

1906: Publishes Freunde geschnitten und gedruckt von Moriz Jung

1907: Designs poster for the Cabaret Fledermaus; begins Wiener Werkstätte postcard work

1906–1915: Official membership in the Wiener Werkstätte

Collective Alchemy: Embracing the Gesamtkunstwerk

The Rise of the Wiener Werkstätte

The Wiener Werkstätte, founded in 1903 by Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser, and Fritz Waerndorfer, had a radical dream: unify high art and daily function, forging an aesthetic environment that stretched from architecture to tableware. This was the Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art,” in action, a concept that insisted every facet of design be woven together to produce an immersive and cohesive experience.

In 1906, Jung was welcomed into this community. For him, the Werkstätte’s vision wasn’t simply a theory—it was lived practice. The organization’s cooperative ethos let him rub elbows with the likes of Hoffmann (revered for his clean lines and geometric flourishes) and Moser (equally adept at painting, typography, and decorative arts). Through these exchanges, Jung became adept at translating modernist impulses into items both whimsical and practical.

Postcards as Microcosms

Of all Jung’s contributions, his postcard designs stand out as vibrant testaments to Vienna’s evolving identity. From 1907 onward, he created around 63 such postcards for the Werkstätte. These are not casual souvenirs; they serve as tiny, portable canvases that reflect a city on the brink of modernity. Their themes stride across a broad spectrum—humor, satire, dogs, cafés, even early aviation. Within these small rectangles of cardboard, Jung’s lines exude an oddly enchanting irreverence, capturing silly or surreal moments that hint at deeper undercurrents of social commentary.

Why postcards? For the Wiener Werkstätte, postcards were a commercial success and also a conduit to popular audiences. Anyone could purchase these pocket-sized art pieces, thus dispersing Jung’s artistry far beyond the typical gallery crowd. For Jung himself, it was a chance to pack satire and color into a succinct format, bridging the gap between fine art and banal object. They were, in many respects, his most direct line to a broad public, and they remain the largest intact portion of his legacy.

Bold Colors, Whimsical Edges

When you look at a Moriz Jung postcard, you notice thick outlines, a playful geometry, and often a palette that toggles between candy-like brightness and soft, muted pastels. Sometimes, a comedic dog meanders into view; other times, a bit of cafe society swirls around in a satirical swirl. This irreverent flair set him apart in an environment teeming with artists jostling for novelty. Each composition seems to wink at the viewer, as though encouraging a second glance to uncover hidden jokes or pointed references.

Primary Pulse of the Wiener Werkstätte Postcards

Approx. 63 designs by Jung

Themes: humor, bizarre scenes, dog breeds, café life, smoking caricatures, aviation satire

Medium for broad distribution, bridging avant-garde and public taste

Major platform for Jung’s recognized style

The Art of Satire: Jung’s Signature Style

Techniques That Spoke Volumes

From woodcuts and linocuts to lithographs and book illustrations, Jung showed an exceptional command of printmaking. Observers often remark upon his uncanny skill at wielding a bold line—sometimes thick and assertive, other times more fluid, lending motion to his figures. Whether the subject was a whimsical beast or a witty commentary on Viennese social mores, Jung found a way to marry humor with narrative clarity.

His color sense often defied predictable harmonies, toggling between eye-popping tones for comedic effect or faint, dreamy hues where the subject demanded a gentler approach. Always, there was a sense of invitation—a quiet dare for the viewer to step closer and parse the underlying visual language. Across his oeuvre, one might spot fantastical creatures, references to Viennese folklore, or cheeky reimaginings of technological marvels like the airplane, which was then both revered and feared.

The Influence of the Secession and Art Nouveau

Vienna during this time was saturated with Art Nouveau’s swirling lines and the Secession’s conceptual leaps. Jung’s work nestles right at that intersection, capturing the lyrical curves reminiscent of Art Nouveau while also flirting with geometric boldness that modernist designs championed. His upbringing in the Kunstgewerbeschule had already attuned him to the principle of “Gesamtkunstwerk”, letting him see no conflict in blending forms, mediums, or styles.

This environment fed Jung’s inclination for thematic variety. A poster for an exhibition would drip with richly saturated colors and symmetrical composition, while a postcard poking fun at a new airplane might display comedic exaggeration. And there was always a subversive glint in his eye: even in seemingly harmless designs, you could find jabs at tradition or sly illusions to the inevitable march of progress.

Unpacking the Whimsical and the Bizarre

One hallmark of Jung’s style is how readily he embraced the eccentric—flying giraffes, facetious mechanized creatures, or dogs outfitted with top hats. These surreal details were more than novelty; they were witty commentary on how quickly newness and absurdity became the norm in early 20th-century society. In truth, his whimsical notes often served as a trojan horse for subtle commentary on social, technological, or even psychological transformations swirling around him.

It’s no stretch to liken his exploration of dreams and fantasies to the era’s broader fascination with the subconscious—a territory also being charted by Sigmund Freud across the city. Jung’s fantasies sketched across postcards and publications might be read as creative metaphors for the unspoken tensions building up in Viennese life. In many ways, his art was a mirror, gently contorted, that revealed the wrinkles of a civilization bracing for rapid change.

Postcards as Cultural Snapshots: A Deeper Dive

The Demand for Miniature Masterpieces

Between 1907 and 1915, the Wiener Werkstätte thrived on postcard sales—an unexpectedly lucrative niche for an avant-garde collective. By virtue of their affordability and easy distribution, these miniature works became a key revenue stream and a public-relations boon. Moriz Jung contributed approximately 63 designs, each shining a spotlight on different facets of Viennese life or modern progress. They weren’t trifling amusements but rather collectors’ items, as many recognized the brilliance and satirical wit poured into them.

Comedic Dogs and Skyscraper Dreams

His postcards covered everything from beloved dog breeds—Greyhound, Bulldog, Pitbull Terrier, Poodle—to flamboyant parodies of the brand-new phenomenon of air travel. One legendary design, “Tête á Tête on the 968th Floor of a Skyscraper,” teases the era’s fascination with height and flight, imagining improbable vantage points that echo both wonder and anxiety. Others, like “Bloodless Giraffe Hunt” or “The Aeroplegasus (Anzani Engines)”, brandish comedic impossibilities, coaxing audiences to chuckle while confronting the dizzying speed of technological shifts.

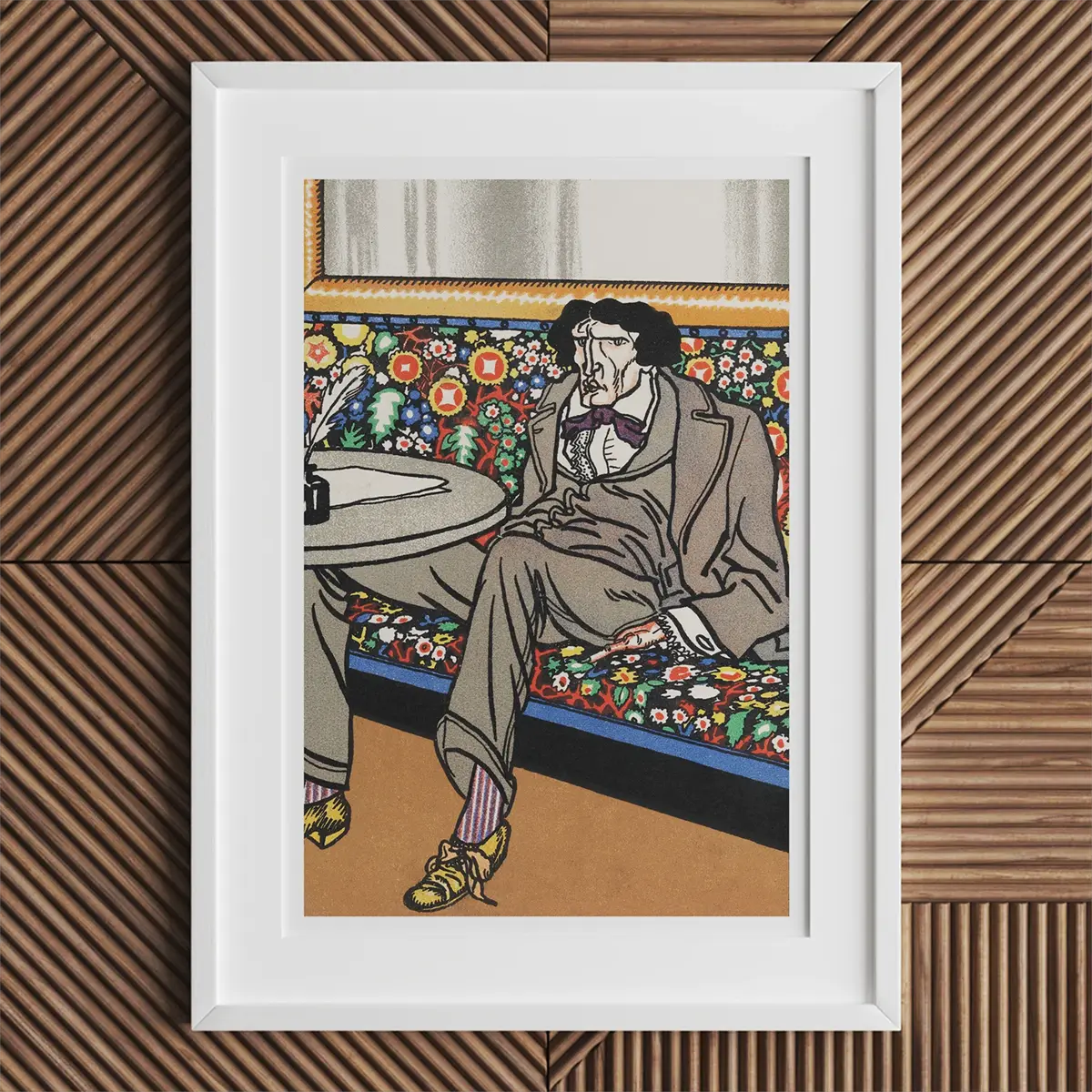

Even everyday Viennese café culture wasn’t immune from Jung’s lens. With the card titled “Viennese Café: The Man of Letters,” he captured the pensive charm of intellectual society, swirling cappuccino cups and simmering gossip. Through these postcards, we see the blossoming tension between optimism for the future and a subtle dread that technology might be outpacing humanity’s comfort zone.

A Glimpse into Society’s Psyche

The postcards’ popularity highlights the public’s hunger for reflective satire, and many of Jung’s designs exude a quintessentially Viennese gallows humor. Under the cheerful color schemes, viewers could sense an undercurrent of anxiety, perhaps unspoken fears of war, or the swirling energies of a city uncertain about how progress would reshape its centuries-old traditions.

Collectors devoured these postcards, storing them in albums or pinning them to parlor walls. Some made their way across the Atlantic or deep into the provinces of the empire, carrying with them a snapshot of Viennese wit—a subtle commentary on society’s rapid metamorphosis. Today, major institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art hold these postcards, underscoring their art historical and cultural significance.

Beyond the Card: Posters, Publications, and the Public Sphere

Cabaret Lights and Kunstschau Brilliance

While the postcards remain his most renowned legacy, Jung’s artistry spilled over into multiple mediums. Even as a student, he crafted a poster for the now-iconic Cabaret Fledermaus, a lively venue in Vienna’s nighttime tapestry. With dramatic lines and vivid color, that early project announced his knack for condensing an event’s essence into a single visually arresting image.

Then came 1908, and with it the Kunstschau exhibition—a lightning rod for avant-garde artists in Vienna. Jung’s posters for this landmark show vibrated with bold lines and brilliant hues, capturing the forward-facing impetus of the city’s artistic vanguard. These designs exemplified the synergy between fine art and graphic design, a principle dear to both the Vienna Secession and the Wiener Werkstätte.

Journals and Satirical Caricatures

Between 1907 and 1914, Jung contributed illustrations to various influential journals—Ver Sacrum, Erdgeist, Der Ruf, and others. Ver Sacrum itself was the official publication of the Vienna Secession, providing a vital platform for new aesthetic philosophies. Meanwhile, Die Fläche (The Surface) showcased the progressive designs emerging from the Secession and Werkstätte, bundling them in a sleek, curated format.

Yet Jung wasn’t confined to high art periodicals. Die Glühlichter, a social democratic magazine, offered him the chance to publish politically tinged caricatures under aliases such as Nikolaus Burger and Simon Mölzlagl. This hidden identity suggests a keen awareness of the political sensitivities of the time. By creating socially critical caricatures without publicly attaching his real name, Jung could tackle controversial subjects—perhaps labor unrest, social inequalities, or the swirling discontent that preceded the outbreak of World War I—with a dose of comedic irreverence.

Book Illustrations: The Merry Pranks and Early Mastery

Among Jung’s other notable pursuits was book illustration. He left his mark in The Merry Pranks of Till Eulenspiegel, infusing the legendary trickster’s escapades with a sense of lighthearted mischief and deft line work. Meanwhile, his 1906 publication, Freunde geschnitten und gedruckt von Moriz Jung, displayed an early mastery of colored woodcuts, especially focusing on animal forms. These parallel endeavors solidified his reputation as a multifaceted talent—neither tethered exclusively to commercial postcards nor limited to decorative trifles.

In each domain—posters, periodicals, books—Jung’s presence signaled a rebellious spirit and a sharp, sometimes satirical vantage. Whether he was hawking a ticketed event, penning a commentary on café life, or weaving visual narratives around a mischievous folkloric character, the throughline was always his ability to engage and sometimes provoke audiences without sacrificing aesthetic allure.

Subtle Laughter, Sharp Commentary: Humor as a Weapon

The Satirical Undertow

While much of Jung’s work can appear lighthearted at first glance, close study reveals layered messages. He had a flair for pointed humor, revealing the inner workings of a society speeding toward modernity. That comedic stance was hardly superficial—it was a means of coping and a mirroring device that let Viennese citizens see themselves in unexpectedly unguarded poses.

For instance, his early airplane caricatures might show a pilot wrestling with improbable contraptions, or civilians gaping skyward in both awe and terror. They wink at the unsettled emotions roused by technology’s new frontiers. Meanwhile, depictions of smokers or café-goers, seemingly benign on the surface, at times carry hints of critique about social norms, perhaps lampooning a city that liked to lounge and gossip while the world’s storms gathered.

Navigating Political Sensitivities

The presence of Jung’s work in Die Glühlichter demonstrates how he straddled the line between whimsical artistry and acute political commentary. Using pseudonyms, he could jab at authority or highlight social inequities without endangering his blossoming reputation in more traditional circles. This dual existence—highbrow artist on one side, satirical critic on the other—testifies to his versatility and courage.

It also underscores how Vienna, though culturally dynamic, was rife with tensions both national and international. By weaving critique into comedic drawings, Jung’s art provided a subtle, safer channel for political discourse that might otherwise be deemed too volatile. In this sense, his cartoons and postcards served as pressure valves, releasing social frustrations through laughter rather than direct confrontation.

A Liminal Darkness

In several postcards, critics have noted an undercurrent of “dark Viennese humor.” This sardonic tone, seldom overt, emerges in moments where the line between delight and distress blurs. Early flight, for instance, was at once an exhilarating promise and a symbol of potential calamity. By exaggerating that tension, Jung nudged viewers to consider the fragility beneath the city’s polished veneer.

One might speculate that these comedic touches were also shaped by the era’s broader psychological climate. With Freud and others delving into hidden depths of the human psyche, and with the empire on the brink of vast reorganization, anxieties naturally seeped into daily life. In Jung’s postcards and caricatures, we see those anxieties satirized, softened by color and line, but potent nonetheless.

When the Guns Thundered: War’s Shattering Call

1914: The Irreversible Turn

As Europe tiptoed into the 20th century, political storms were gathering. 1914 marked a seismic change, with World War I detonating illusions of stable peace. In that year, the same year that crackling optimism was in full bloom, Moriz Jung was called up for military service. Suddenly, his sketches and postcards, radiant with humor, were replaced by the unforgiving reality of trench warfare.

In a poignant reflection, Jung remarked, “All doubts about vocation and the like have disappeared, blown away in the thunder of the guns.” Here, we glimpse a mind grappling with the collision of artistic devotion and patriotic duty. Though the exact nuance of this statement remains open to interpretation—was it resigned acceptance or stoic determination?—it underscores the depth of conflict swirling around him and countless others.

Wounded in Galicia

By September 1914, the war’s brutality had already caught up with him. Stationed in Galicia, he suffered a gunshot wound in his left thigh. Gravely injured, he paused only briefly to recover before returning to the front lines. Such an injury, though severe, did not remove him from service; in the relentless churn of war, convalescence was fleeting, and the frontline beckoned again. This forced immersion in violence stood in stark contrast to the colorful, inventive world he had cultivated.

The Final Blow: March 11, 1915

Amid the winter-long Carpathian Battle, with combat raging on snowy ridges, fate dealt its most decisive blow. On March 11, 1915, at just 29 years old, Moriz Jung was killed on the Manilowa Heights near the village of Łubne, south of Baligród. This shocking news reverberated through the Viennese art community, sending waves of grief through workshops, salons, and cafés where his postcards had become a cherished staple.

Newspapers like the Prager Tagblatt and the Fremden-Blatt published obituaries lamenting the loss. The Fremden-Blatt labeled him “one of the most gifted caricaturists of the modern Viennese school,” a fitting testament to his unique comedic gift and incisive perspective. Thus, an entire trajectory of possibility—new prints, fresh satirical takes, further expansions into design—was halted midstream. The reverberations of his death were palpable, leaving many to wonder what further brilliance might have emerged had he survived.

Reckoning with Legacy: Echoes of Brief Brilliance

The Vacuum Left Behind

Vienna, a city that cherished Jung’s comedic irreverence, felt the sting of his loss profoundly. His short career had intersected with the capital’s most dynamic period of artistic innovation. The postcards, posters, book illustrations, and caricatures hinted at a prolific lifetime to come, yet it all ended in an instant along a snowy battlefield. His passing was not just another casualty statistic—it was the loss of a distinctive voice in a chorus that would never be the same.

While the war raged on and eventually reshaped the map of Europe, those who encountered Jung’s art remembered him as an innovator, a comedic observer who gently peeled away the city’s façade. The tragedy was especially acute given his youth: at 29, he’d barely begun to trace the contours of what could have been a transformative artistic journey.

Residual Imprints: Museums and Exhibitions

Nonetheless, Moriz Jung refused to vanish into history’s dustbin. His works found their way into prestigious collections worldwide; the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City holds an impressive archive of his Wiener Werkstätte postcards. Exhibitions focusing on the Vienna Secession and the Wiener Werkstätte regularly spotlight these colorful curios, ensuring that new generations continue to encounter—and delight in—his imaginative visions.

From the vantage of art history, Jung represents a crucial bridge between the flowing lines of Art Nouveau and the starker geometric forms that would soon come to define the next wave of modernism. His postcards—mass-produced yet meticulously designed—embody the core principle of the Gesamtkunstwerk, breathing artistry into an everyday, affordable format. Even after over a century, these seemingly small trifles remain beloved by collectors and scholars, proving that genuine art transcends the boundaries of scale or context.

Ripples Without Direct Descendants

While there is no extensive documentation of artists who directly modeled their style on Jung, the broader aesthetic influences of the Wiener Werkstätte are far-reaching. By all accounts, his vision seeped into the era’s general currents of satirical commentary and design synergy. Today, with the postcards in the public domain, a global audience has digital or physical access to these whimsical microcosms of imperial Vienna’s last gasp.

Even if we cannot chart a direct artistic “school” that follows him, his legacy endures in the unmistakable linework, the playful humor that shows up in so much of 20th-century European graphic design. The intangible gift he left is the permission to be bold, humorous, and sly, all at once—reminding us that commentary can be made more potent with a grin.

A Fleeting Spark with Lasting Light

Moriz Jung's Legacy

Moriz Jung, with his 29 years of life, sketched a panorama of satire, color, and social reflection that remains undiminished by time. Though the thunder of cannons ended his journey on March 11, 1915, the imprint he left lingers in museum collections, historical retrospectives, and the hearts of those who resonate with his playful approach to life’s deeper churn.

His story is one of expanding possibility suddenly cut off, a reminder of how war can extinguish the brightest talents. But it’s also a testament to the resilience of art: postcards slip across borders, subversive caricatures are preserved in archives, and imaginations spark anew whenever an observer catches the sly grin on a dog’s face or an aviator’s improbable contraption. In the swirl of a city famed for waltzes and coffeehouse discussions, Jung’s memory persists as a quiet but undaunted presence—a fleeting brilliance whose afterglow still brightens the world of design and illustration.

His postcards, still revered, form the keystone of his enduring influence. They evoke a Vienna of laughing exteriors and anxious interiors, a city poised to break from the past yet tethered by centuries of imperial tradition. In their playful lines, we discover the reflection of a collective psyche eager to move forward, uncertain how to do so, and unwittingly poised on the brink of catastrophe.

Through his short but shining career, Moriz Jung emerged as a messenger of wit, a craftsman of applied modernism, and a chronicler of the comedic and the strange. Even now, new researchers and casual admirers stumble upon his postcards or a snippet of his biography and find themselves captivated. His bold lines, whimsical creatures, and satirical glimpses of progress speak to us across time, saying: Yes, life can be absurd, and artistry all the more necessary for it.

In that sense, the flicker of Moriz Jung’s genius transcends the century that separates us, urging each new generation to look closely, laugh freely, and remain aware of the fragile illusions we call progress. The final, unfinished canvas of his life reminds us that beauty and humor persist—even when humanity succumbs, however briefly, to darkness.

Reading List

- Hoffmann, Josef, and Koloman Moser. The Wiener Werkstätte: Design in Vienna, 1903–1932. Munich: Prestel Publishing, 2003.

- Jung, Moriz. Freunde geschnitten und gedruckt von Moriz Jung. Leipzig and Vienna: 1906.

- Kallir, Jane. Vienna 1900: Art, Architecture & Design. New York: Abrams, 1986.

- Long, Christopher. Josef Frank: Life and Work. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art. "Wiener Werkstätte Postcards." Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013.

- Vienna Secession. "Jung, Moriz." Vienna Secession, 2017. (theviennasecession.com)

- Wikipedia. "Moriz Jung." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, last modified July 2024. (en.wikipedia.org)

- Witt-Dörring, Christian, and Janis Staggs. Wiener Werkstätte Jewelry. New York: Neue Galerie, 2008.