Look closer: the canvas begins to tear, and through the breach, the 20th century stares back. In the shifting panorama of modern art, Pablo Picasso doesn’t merely loom—he fractures the horizon itself. Not just with paint, but with scraps of lived life—newspaper clippings, torn wallpaper, ticket stubs still fragrant with yesterday’s smoke. His career was not a series of paintings hung end to end but a seething, restless architecture of disruption. And collage—the radical fusing of matter and idea—became the fault line on which he danced.

This guide maps that earthquake. We will not tiptoe along the edges. We will wade into the combustible marrow of Picasso’s collage art—where paint and paper mate like strange alchemists, where reality splinters and recombines, and where the old vocabulary of art trembles under the pressure of a new lexicon.

We’ll trace the cracked but fertile lineage of influences that pressed Picasso toward collage—ancient Iberian sculptures, the vibratory pulse of Parisian streets, the thrum of African masks calling from across oceans and time. We’ll watch as he and Georges Braque, wrestling like two mythic beasts, invented a new syntax: Cubist collage, a grammar of geometries and ruptured sightlines that demanded audiences learn how to see all over again.

We will slice through the audacious methods he pioneered—papier collé, synthetic Cubism, and the irreverent insertion of the real into the representational—and glimpse the stunned reactions that echoed across ateliers and academies alike. This journey is no polite museum tour. It is an immersion into the roaring furnace where tradition was torn apart and reassembled into something unruly, new, and alive.

In the shards, in the juxtapositions, in the stubborn refusal to let paint alone suffice, Picasso’s collage works build a world truer than realism ever dared. Prepare to see art not as a mirror but as a rupture—each fragment singing with possibility.

Key Takeaways

-

Uncover the historical forces that drove Picasso toward collage art, from the energetic chaos of early 20th-century Paris to the aesthetic disruptions of Iberian and African art forms that fueled his experimentation.

-

Explore the revolutionary aesthetics of Cubist collage, where geometric fragmentation, mixed media layering, and simultaneous perspectives dismantled traditional visual narratives.

-

Learn about Picasso’s innovative collage techniques and materials, including his pioneering use of papier collé, synthetic compositions, and the incorporation of everyday objects like newspapers, rope, and oilcloth into fine art.

-

Examine the critical collaboration between Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, whose artistic dialogue and rivalry ignited the invention of collage as a dominant force within modernism.

-

Decode the symbolic and abstract themes embedded in Picasso’s collage art, where fragmentation, reality-disruption, and material hybridization create layered meanings beyond surface appearance.

-

Recognize Picasso’s transformative influence on contemporary collage artists, tracing how his radical materiality and conceptual daring continue to shape assemblage, mixed media, and digital collage practices today.

-

Gain a deeper understanding of Picasso’s iconic collages, such as Still Life with Chair Caning and Guitar, Sheet Music, and Wine Glass, which shattered conventional boundaries and redefined the possibilities of visual art.

The Dawn of Pablo Picasso's Collage Art

In the ferment of early Cubism, Picasso’s innovation was both inevitable and explosive. Collage, drawn from the French coller—to glue—offered an irresistible pivot away from mimetic surface toward material experimentation. Here, paint alone would no longer suffice. Newspapers clotted with daily chaos, oilcloth imitating chair caning, battered wallpaper strips—all pressed themselves into the syntax of art, demanding their place not as illusion, but as participants in the visual conversation.

Picasso’s philosophy rippled through the torn edges: "When I haven't any blue, I use red." Adaptability was not compromise; it was the engine of invention. In his hands, everyday objects escaped banality and entered the sacred field of composition. Picasso’s early collage works embodied this principle, asserting that the real—the physical detritus of modern life—was just as ripe for aesthetic transformation as pigment and brushstroke.

The evolutionary leap in artistic technique he achieved was seismic. Abandoning the exclusive rule of the brush, Picasso wielded scissors and adhesive like a cartographer of new visual continents. Early Cubist collage techniques layered fragment over fragment, obliterating the singular viewpoint and birthing the simultaneous perspectives that would become Cubism’s beating heart.

Cultural forces churned beneath this breakthrough. Paris, dense with periodical presses, café chatter, and industrial textures, shaped the raw material landscape that Picasso cannibalized for his experiments. Meanwhile, African art influences, Iberian sculpture, and the intellectual partnership with Georges Braque fermented a stylistic alchemy that propelled collage art into avant-garde dominance.

Yet this nascent revolution was more than technical. The origin of collage art within Picasso’s practice signaled a philosophical rupture: the collapse of representation into construction. By embedding life’s rough textures into his compositions, Picasso heralded a new era where art no longer imitated the visible world—it assembled its debris into new meaning.

Thus, in the earliest slices of paper and glue, we see Picasso unmaking and remaking the possibilities of art. In every jagged edge, in every pasted scrap, modernity took root—raw, ruptured, and irreversibly alive.

Examining Picasso's Cubist Collages

To step into the disassembled geometry of Picasso’s Cubist collages is to feel the tectonic plates of vision shudder underfoot. In the radical workshops of Cubism, Picasso did not simply rearrange appearances; he atomized them. His Cubism collage innovations tore objects from their skin and rebuilt them along invisible axes—truths seen sideways, time compressed into a single flattened plane.

The defining characteristics of Cubist collage by Picasso announce themselves in sharp, almost rebellious precision. Geometric simplification slices through tradition: bottles, violins, glasses collapse into facets of triangle and curve, their identities flickering between abstraction and recognition. It was not just fragmentation; it was reconstitution, an aesthetic alchemy where the familiar was burned down to be reassembled under new laws.

The interplay of texture formed another axis of revolution. Rather than feigning depth through oil alone, Picasso incorporated real materiality into the surface: gritty sand, coarse burlap, printed text, and patterned wallpapers. This mixed media integration shattered the illusionistic tricks of painting. Canvas ceased to be a mere window into a scene—it became a tactile arena where meaning wrestled directly with matter.

Across these collages, overlapping planes disrupted and confounded traditional space. Edges blurred; foregrounds folded into backgrounds; perspective became a jigsaw puzzle of angles and glimpses. Rather than creating the illusion of three-dimensional space, Picasso flattened the world into layers of implication, demanding the viewer reconstruct reality piece by piece.

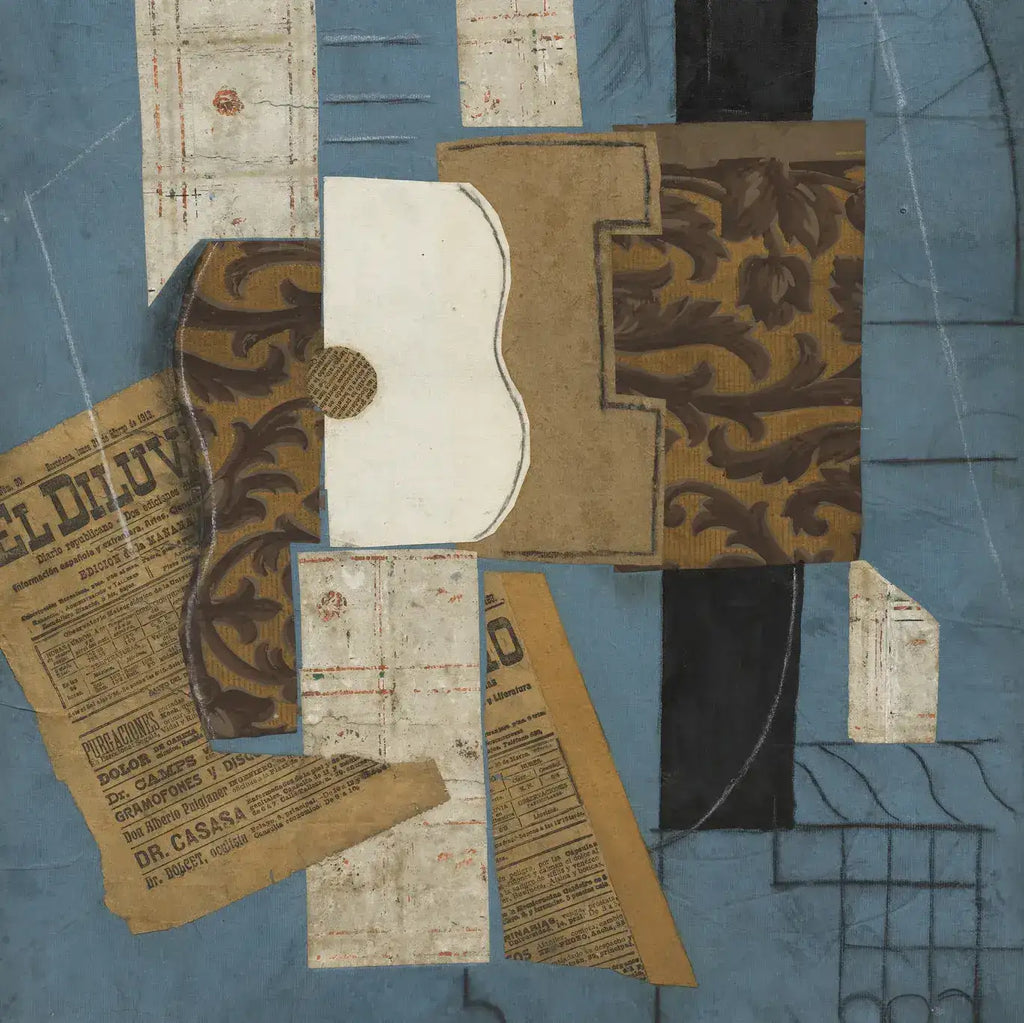

This method matured into what historians term the synthetic approach—a second phase of Cubism where disparate elements were assembled to evoke objects not through outline, but through contextual suggestion. A sliver of newspaper became a guitar’s soundhole. A wallpaper scrap conjured a café table. Representation was no longer rendered; it was evoked, collaged from the residues of everyday life.

"I paint objects as I think them, not as I see them," Picasso proclaimed, severing ties with the Renaissance mirror and ushering in the age of conceptual primacy. Through this rupture, conceptual representation overtook visual imitation as the heartbeat of modern art.

The impact was seismic. Picasso’s Cubist collages seeded the future fields of assemblage art, where found objects would create new grammars of form. They prefigured the philosophical fractures of abstract expressionism, where emotion displaced depiction. They ignited new visual dialogues that insisted art be not only seen but deciphered.

Ultimately, the conceptual evolution in art catalyzed by Picasso’s Cubist collages redefined the very stakes of creativity. No longer could art merely seduce the eye—it had to challenge, confuse, rebuild the mind. In the angular echoes of paper and glue, a new century of perception was born.

The Innovative Technique Behind Picasso's Collages

Pablo Picasso, Women at Their Toilette (1937–38 CE)

Inside Picasso’s studio, matter itself seemed to mutiny. The familiar textures of the everyday—newspapers smudged with yesterday’s hands, scraps of wallpaper whispering floral fatigue, bits of rope still smelling of the docks—rose up and demanded to be seen anew. The artist, ever conspiratorial with chaos, listened. Thus was born Picasso’s collage techniques, a quiet revolution stitched from the overlooked.

Material diversity stood at the core of this insurgency. In lieu of mere pigment, Picasso deployed fragments of life itself. Through material experimentation in collage art, he dragged the tangible world—paper, fabric, sand, string—onto the sanctified plane of high art. No texture was too humble; no scrap too trivial. Art was no longer a mirror to reality but a hybrid skin stretched taut over it.

Yet it was not mere accumulation that defined his genius. It was the layered orchestration of meanings. In Picasso’s hands, conceptual layering in collage became an act of synthesis: disparate elements fused not just physically but ideologically. A sheet of newspaper did not merely depict news; it became commentary, sedimentary proof that life itself could be folded into art’s anatomy.

His approach to spatial reconstruction in collage art dismantled the classical laws of depth and surface. With calculated disobedience, Picasso overlapped, juxtaposed, and interwove visual elements to birth new dimensionalities. Space was no longer a passive stage; it was a participant, an accomplice in the unfolding tension between surface and illusion.

Frequently, these collages began with modest foundations—a stretched canvas, a wooden board—and grew outward through instinctive accumulation. Each layer a decision, each addition a rupture, each fragment a declaration that reality was polyphonic, nonlinear, unfixed.

Central to this technique was the daring integration of papier collé, a method Picasso and Braque pioneered during the Cubist experiments. Unlike painting, which feigned materiality, papier collé techniques embedded real textures directly into composition, stitching art and artifact together with irreverent candor.

"The purpose of art is washing the dust of daily life off our souls," Picasso mused, and his collage works embody that credo.

Through these layered innovations, Picasso's collage methods transformed the canvas into a contested territory where meaning, material, and imagination sparred in open daylight. Every glued edge, every torn paper seam, spoke of a world not simply observed but physically reconstituted—piece by jagged piece—into something truer than imitation could ever hope to be.

Picasso's Artistic Breakthrough: Was Picasso a Collage Artist?

In the long, combustible arc of modern art, few questions smolder quite like this: Was Pablo Picasso, fundamentally, a collage artist? Peel back the varnish of convention and the answer flares unmistakably: collage was not his detour. It was his crucible. His innovations in paper collage did not merely extend his repertoire—they detonated the very definitions of painting, sculpture, and visual meaning.

The significance of paper collage in Picasso’s work cannot be overstated. It was within these torn and pasted assemblies that Picasso found a new creative bloodstream—one liberated from the weight of traditional draftsmanship. The malleability of paper, its vulgar ordinariness, became his key to breaching the rigid sanctity of oil on canvas. A scrap of newsprint, a wallpaper fragment, a wine label—they did not mimic life. They carried it, pulsing and immediate.

Through collage, Picasso achieved a level of creative liberation unprecedented in visual art. Freed from illusionistic bondage, he allowed instinct to lead: a shift here, a rupture there, an accidental tear became a deliberate intervention. The canvas ceased to be a stage for representation and became an active participant, a vessel of both improvisation and profound control.

Innovation with material was paramount. In works like Bottle of Vieux Marc, Glass, Guitar and Newspaper (1913), Picasso integrated found printed ephemera with drawing and oil paint, pioneering a radical hybrid aesthetic. This collage as fine art challenged the long-entrenched hierarchies that separated the “noble” from the “everyday.” In his hands, the refuse of modernity was transfigured into icons of artistic audacity.

The conceptual breakthrough was seismic. Rather than reflecting external reality, Picasso’s collages proposed an art of internal logic, assembled thought, and perceptual flux. Collage as a conceptual form revealed that materials were not merely supports for images—they were active components of meaning itself.

This evolution crowned Picasso among the modern collage pioneers, artists who dismantled the visual codes of centuries and rebuilt them from the battered syntax of real life. By embedding ordinary materials into his compositions, Picasso rejected the idea that fine art must exist apart from lived experience. He folded the noise of the street, the ephemeral buzz of café culture, and the tactile urgency of daily life directly into the marrow of modernism.

Ultimately, Picasso’s collages were not supplemental experiments. They were declarations. He was not merely a painter who dabbled in collage. He was an architect of rupture—a builder of new worlds from torn seams.

Picasso and Braque: Pioneers of the Paper Collage Technique

Pablo Picasso, The Bottle of Vieux Marc (1913 CE)

At the molten center of Cubism’s upheaval, two minds collided and fused: Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Their collaboration was not mere partnership—it was catalytic fusion, an intellectual and material symbiosis that would give birth to one of modern art’s most seismic innovations: the invention of paper collage.

In the crucible of 1912, these two artists—already dismantling form and perspective through analytic Cubism—recognized that depiction was no longer enough. Reality needed to be annexed, grafted directly onto the picture plane. Thus emerged papier collé, a radical advance where fragments of commercial printed paper, faux-woodgrain wallpaper, and newspaper clippings entered the arena of high art without apology.

The Picasso and Braque collage collaboration thrived not on competition, but on reciprocal provocation. Braque’s discovery of the woodgrain wallpaper sheet—cut and affixed like a secret trapdoor in a visual composition—ignited a wildfire of experimentation in Picasso’s studio. Conversely, Picasso’s irreverent layering of material inspired Braque to push the aesthetic boundaries further, into realms where brushstrokes and glued surfaces argued and harmonized on the same canvas.

Their material abstraction techniques redefined the conditions of perception itself. No longer was a violin simply painted—it was suggested through the shape of a newsprint curve, the rough peel of wallpaper mimicking wood, the flash of pasted lettering evoking musical notation. Reality became a construction, an act of creative interpolation between fragments.

In embracing Synthetic Cubism, Picasso and Braque did not just add materials; they invented a new way of thinking about visual language. By introducing pre-formed textures and objects into their compositions, they forced the viewer into active collaboration—decoding, interpreting, reconstructing the implied image from shards of the real world.

"There is only one valuable thing in art: the thing you cannot explain," Braque mused, and the collages he and Picasso produced thrum with precisely that irreducible mystery. Every glued scrap, every torn edge challenges the boundaries between painting and sculpture, between art and artifact.

Thus, Picasso and Braque must be recognized as the true Synthetic Cubism pioneers—artists who demolished the illusionistic traditions of Western art and reassembled a new visual architecture from the rubble. Their invention of paper collage not only fractured the picture plane; it fractured time, space, and expectation itself, ushering in a modernity where fragmentation became the native tongue of seeing.

Together, they did not just capture the world. They reassembled it, piece by subversive piece.

Exploring the Multifaceted Meanings in Picasso Collage Art

Within Picasso’s collages, every scrap and suture hums with encrypted resonance. These are not mere assemblages of paper and pigment—they are coded constellations, systems of signs stitched into material form. To truly engage with Picasso collage symbolism is to step into a labyrinth where meaning refracts endlessly, never static, never singular.

"Art is a lie that makes us realize truth," Picasso provocatively declared—a sentiment that encapsulates his approach to collage, where representation intertwines with reality to evoke a more profound veracity.

At the heart of his approach is a fierce commitment to an abstract visual language. Each torn newspaper fragment, each sliver of musical score or cafe advertisement, becomes a glyph—a visual syllable contributing to an artwork’s polyphonic discourse. Reality itself is stripped for parts, then reassembled into puzzles that defy easy translation.

Recurring motifs pulse through Picasso’s collages like blood through arteries. The omnipresence of musical instruments—guitars, violins, sheet music—signals a fascination with harmony and dissonance, structure and improvisation. Yet beyond surface references, these motifs also hint at the fragmented nature of human perception itself: melody disrupted, wholeness shattered, then reconstructed anew.

Embedded within these fractured compositions are potent acts of political commentary through collage. The intrusion of newspaper clippings, often barely legible yet unmistakably present, roots Picasso’s abstractions in the volatile churn of early 20th-century Europe. The domestic becomes public, the ephemeral becomes historical—each pasted headline a reminder that no artwork can escape the tremors of its time.

The dominant visual strategy here is fragmentation—not as destruction, but as revelation. Through the fragmentation of reality in Cubist collage, Picasso invites viewers to experience the world as a palimpsest of shifting layers. Perspective fractures. Meaning shatters. Certainty dissolves into overlapping viewpoints and simultaneous truths.

This radical rupture is not without tenderness. Interplay between daily life and collage art emerges in Picasso’s insertion of the banal into the grand: the humble wine label, the sliver of wallpaper, the frayed rope fragment. In elevating these artifacts of everyday existence, he blurs the line between high and low culture, insisting that beauty—and significance—reside in the overlooked and the transient.

Underneath these gestures thrums a profound exploration of Cubist semiotics: the belief that signs and symbols carry elastic, mutable meanings. A pasted word, a jagged silhouette, a drawn contour—each can shift valence depending on context, proximity, and perception.

In Picasso’s collages, then, we find not fixed narratives but living riddles—dense fields of signification that pulse with life long after the glue has dried. They do not ask to be solved. They demand to be inhabited.

The Legacy of Picasso's Collages in Contemporary Art

Pablo Picasso, The Violin (1914 CE)

The shrapnel of Picasso’s collage revolution still ricochets through the halls of contemporary art. His audacious acts of fragmentation and reassembly laid the genetic blueprint for an entire lineage of artists who continue to mine, mutate, and magnify the possibilities he first cracked open. The impact of Cubist collage did not end in salons or manifestos; it erupted into an enduring, ever-evolving force that pulses through today’s creative fields.

Picasso's influence on modern collage is omnipresent. His insurgent use of mundane materials—newspapers, wallpaper, rope—sanctioned a permanent collapse between high art and daily life. Contemporary artists inherit this license to fuse the ephemeral with the profound, the discarded with the sacred. They wield the aesthetic DNA he encoded, pushing collage from canvas to street wall, from paper to pixel.

The seeds Picasso planted now bloom in the wild gardens of contemporary collage techniques. Artists like Mark Bradford scrape urban detritus into monumental visual archives, while Kara Walker’s silhouettes splice history, trauma, and myth with surgical precision. The thread binding them to Picasso’s legacy is not imitation but evolution: an inherited instinct for rupture, layering, and material storytelling.

Crucially, Picasso’s collages also set the precedent for conceptual expansion. Today’s collage artists engage not just with texture and surface but with politics, identity, and hybridity—territories Picasso first staked when he glued the modern world’s scraps into works that demanded to be seen as more than mere decoration. This expanded field reveals the legacy of Picasso collage methods as a deep structural shift: from painting as depiction to collage as argument.

In the digital age, his ghost flickers in unexpected places. Photoshop montages, AI-assisted composites, and glitch aesthetics echo the fundamental lessons of Cubist collage: break it, rebuild it, say it slant. Where Picasso cut and pasted by hand, contemporary artists slice and fuse across screens and servers, expanding the reach of collage into the immaterial realm.

Yet even amid technological torrents, the essence remains tactile. The enduring influence of Picasso’s collages lies not merely in technique but in philosophy: the belief that meaning emerges from fragmentation, that the real and the imagined are not opposites but dance partners.

Picasso did not simply invent a medium. He ignited a contagion of creativity—a viral logic that continues to morph, adapt, and roar through the fractured, reassembled visions of every generation that dares to tear reality apart and start again.

Iconic Picasso Collages That Shaped Modern Art

Some artworks do not merely hang on walls—they detonate across epochs. Among the iconic Picasso collages, few ripple louder through the veins of modernity than Still Life with Chair Caning (1912), a work that tore open the traditional frame and dared art to never again close it.

In this pivotal piece, Picasso embedded an actual oilcloth printed with a chair-caning pattern onto the canvas, framing it with a length of thick rope. The gesture was both playful and insurrectionary. In any Still Life with Chair Caning analysis, what emerges is not simply an aesthetic innovation but a philosophical rebellion. The canvas no longer pretends to be a window—it becomes a hybrid object, collapsing illusion and material reality into a single surface.

Through this act, Picasso executed a coup against centuries of representational decorum. The humble oilcloth did not simulate texture; it was texture. The rope did not depict a border; it was the border. In one audacious move, he made the everyday tactile and the symbolic literal, anchoring Cubism’s next leap forward: the transition from analytic dissection to synthetic construction.

"When we invented Cubism, we had no intention whatsoever of inventing Cubism. We wanted simply to express what was in us." – Picasso

Picasso’s Cubist collage masterpieces form a constellation of radical ruptures. Pieces like Guitar, Sheet Music, and Wine Glass (1912) and Bottle of Vieux Marc, Glass, Guitar and Newspaper (1913) continue the assault on surface expectations. In these compositions, fragments of sheet music, tobacco labels, and newsprint are not ornamental—they are structural, forming the skeletons upon which visual meaning precariously hangs.

In each, texture is narrative. Material carries memory. The debris of the street corner and the bistro table find themselves transfigured into cultural artifacts, collapsing the division between art and life, elite and vernacular.

Through these Cubist collage masterpieces, Picasso did more than invent new visual tactics. He reengineered how viewers must approach art itself: not as passive recipients, but as participants piecing together fractured realities. His use of found materials was not simply clever—it was a demand that modern life, with all its chaos and ephemerality, be recognized as the true palette of the new century.

These works stand today not as relics but as active tectonic forces. In every torn edge, in every glued seam, in every battered scrap, the future of art still trembles—waiting, beckoning, daring the next hand to rearrange the world anew.

The Enduring Influence of Picasso's Collage Art

Pablo Picasso, Guitar (1913 CE)

The tremor Picasso unleashed through collage never settled. It ripples outward still, agitating canvas, sculpture, screen, and street. The Picasso collage legacy is not one of static artifacts admired at distance, but of a living contagion—a method, a mentality, a provocation inherited by generations unwilling to leave surfaces undisturbed.

His collages rewrote the terms of artistic engagement. No longer confined to brush and illusion, artists found permission to build with the flotsam of modern life. The lasting impact of Cubist collage manifests not only in aesthetics but in a shift of consciousness: that fragmentation could be revelation, that debris could be language, that rupture could be a form of radical clarity.

The influence of Picasso collage art is visible wherever material meets meaning. Assemblage, installation, conceptual art—all bear his fingerprints. Artists such as Robert Rauschenberg, who layered found imagery into hybrid visual landscapes, or Jean-Michel Basquiat, who stitched text, symbol, and paint into electric fields of meaning, trace their lineage back to Picasso’s first audacious acts of adhesion and disruption.

In contemporary practice, the inheritance mutates but never fades. Digital artists layering glitch, found footage, and archival fragments into screen-based collages echo the same impulse that once drove a pasted newspaper clipping into a Cubist still life. Street artists stapling torn posters and stenciled slogans onto urban walls perform, knowingly or not, acts of contemporary art inspired by Picasso—collage as public memory, as protest, as fleeting monument.

Yet it is not merely technique that endures. It is Picasso’s deeper assertion: that art must not merely depict reality—it must engage with it, digest it, rupture it, and reconfigure it into new forms of knowing. His collages insist that creation begins where wholeness fractures.

Even now, to tear, to paste, to layer—to physically intervene in the material world—is to participate in a lineage Picasso electrified. His legacy is not a style to be mimicked but a challenge to be answered: to recognize the beauty in disorder, to construct new harmonies from noise, to find meaning in the seams.

In every contemporary collage that dares to stitch together the discarded and the sacred, Picasso’s revolution lives on—raw, unsettled, and fiercely alive.