In the late 19th century, a certain magnetic glow seemed to follow John Singer Sargent wherever he set up his easel. His swift, unerring brushwork and incisive eye for detail would come to define a cultural moment we now recall as the Gilded Age, capturing the ambition, elegance, and hidden tensions of a world in flux.

Critics dubbed him a master portraitist, but his gifts ranged far beyond the drawing rooms of aristocracy. Wandering through Europe as a youth, immersing himself in the dynamism of Spanish flamenco or the bustle of North African bazaars, Sargent gained a breadth of vision that spilled onto every canvas he touched.

From regal London salons to the restless streets of Paris and New York, he distilled an era’s spirit—an era steeped in opulence yet haunted by a whisper of fragility.

This sweeping talent shaped a legacy that reverberates to this day, and understanding Sargent means tracing the restless arc of a painter who refused to stay in one place—artistically, culturally, or geographically.

Despite the elegance of his formal portraits, he was, in many ways, an American nomad: a society’s wanderer, forever bridging the old world and the new.

Key Takeaways

- Discover how John Singer Sargent became the quintessential portrait painter of his time.

- Learn about the unique integration of Impressionist techniques in Sargent's portraits.

- Appreciate the breadth of Sargent's oeuvre, including his landscapes and murals beyond society portraits.

- Uncover the profound personal and cultural depths revealed in Sargent's paintings.

- Examine the lasting influence of Sargent on American art and his continuing relevance in modern times.

- Explore the richness of Sargent's art and its capture of an era's spirit in vivid detail.

Making of a Master: John Singer Sargent as an American Expatriate

Unknown photographer, John Singer Sargent in the Alps (1910–11 CE)

John Singer Sargent's journey began amidst the art-laden beauty of Florence, Italy, where his early years were as vivid and unconventional as the brushstrokes that would later define his art. Born into a cosmopolitan expatriate family, Sargent's youth was marked by an itinerant lifestyle—his parents carried him through Europe's cultural epicenters, offering him an education immersed in the grand traditions of Western art.

The rich textures of Tuscany formed the backdrop for his formative years, filled with museum visits and lessons in the grandeur of Renaissance art. Sargent's mother, Mary, a Philadelphia heiress and amateur watercolor artist, fostered in him a perpetual love affair with the visual world, despite societal pressures that discouraged women from pursuing such passions. Mary’s relentless pursuit of beauty and culture drove the family across Switzerland, Paris, Salzburg, Milan, Genoa, and Rome, nurturing her son's burgeoning artistic talent.

Sargent’s education was unconventional. As permanent itinerants, his family rarely had the resources for traditional schooling, so his father provided a 19th-century version of homeschooling, focusing on whatever opportunities their travels presented. Museums, libraries, gardens, and ancient ruins became Sargent’s classrooms, giving him a uniquely immersive education that embedded a curiosity and versatility into his artistic practice.

Carolus-Duran and the Influence of the Old Masters

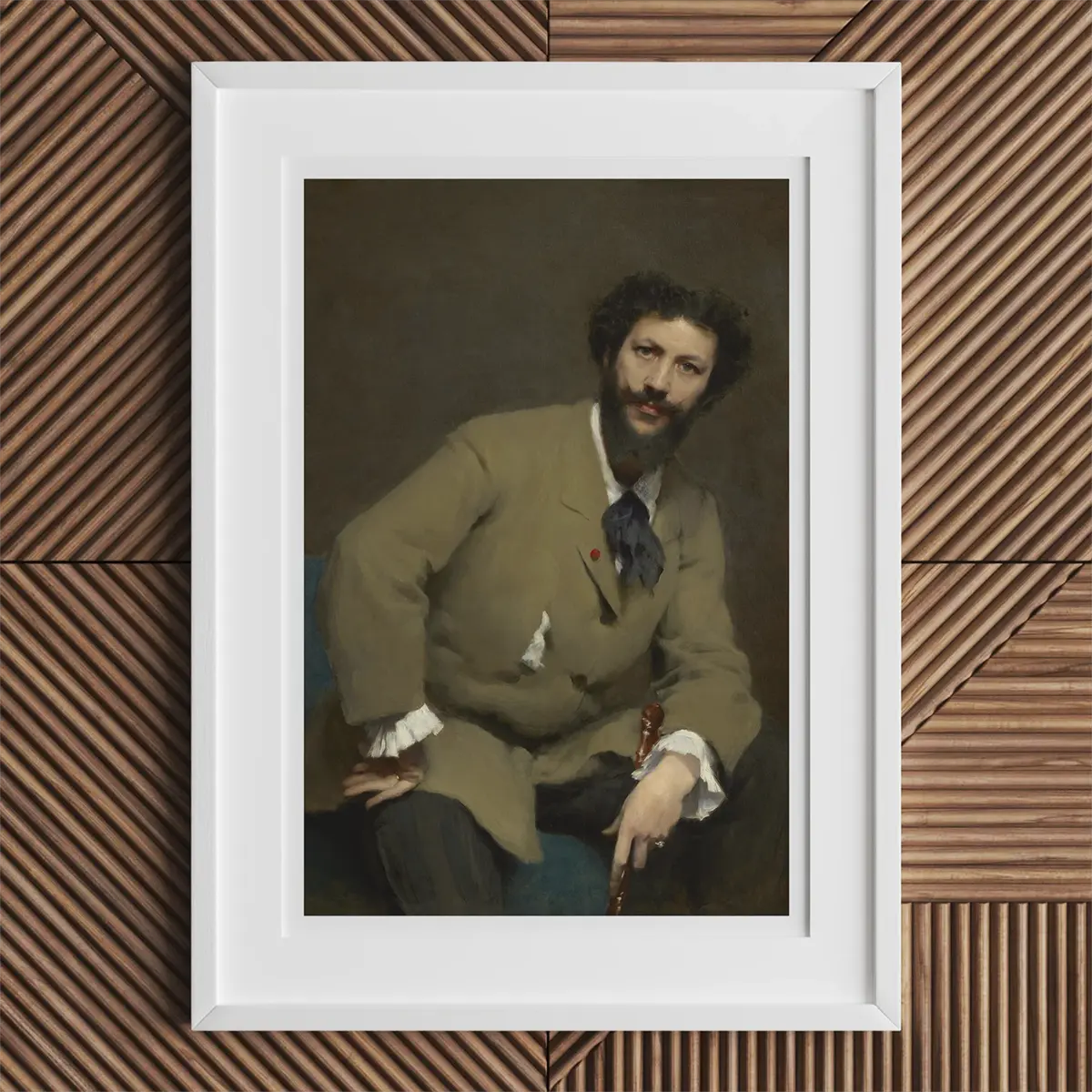

John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Carolus-Duran (1879 CE)

Sargent’s father had hoped he might become a naval officer, but it quickly became clear that John’s passion was for art. In 1874, at age 18, he moved to Paris, then the center of the art world, to formally train as a painter. He enrolled in the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts and, crucially, entered the independent atelier of Charles Auguste Émile Durand, better known as Carolus-Duran, a fashionable portraitist famed for his modern technique. Under Carolus-Duran’s mentorship, Sargent was pushed to abandon timid academic brushwork in favor of bold, direct painting.

Carolus-Duran insisted his students paint au premier coup, or “at the first touch” – a form of alla prima technique involving applying paint wet-on-wet with confident strokes. This method encouraged a broad, painterly style and required technical precision and courage in equal measure. Sargent embraced this radical approach, quickly mastering the art of capturing a scene or a sitter in a single, spirited go. His ability to “draw with a brush,” rendering forms with fluid yet accurate strokes, would become a hallmark of his work.

While honing his craft in Paris, Sargent also steeped himself in the legacy of the Old Masters. Carolus-Duran, who admired the 17th-century Spanish painter Velázquez, directed Sargent to study the great European masters like Diego Velázquez, Rembrandt, and Titian.

In 1879, Sargent traveled to Madrid to copy Velázquez’s paintings in the Prado, and the following year to Holland to study the expressive brushwork of Frans Hals. These influences shaped Sargent’s artistic identity profoundly. From Velázquez he absorbed a sense of composition and tone, from Hals a looseness and life in brushwork, and from Rembrandt a penetrating insight into character.

By his early twenties, Sargent was synthesizing these Old Master influences with modern techniques, achieving what one critic would call une simplicité savante – a “skillful simplicity” that made his work at once classically informed and strikingly fresh.

Alla Prima Portraits and the Power of Realism

Under Carolus-Duran’s tutelage, Sargent blossomed into a technical prodigy. He astonished instructors and peers by winning honors at the Paris Salon while still in his early twenties: an Honorable Mention in 1879 for his portrait of Carolus-Duran himself, and a Second Class medal in 1881 for a portrait of Madame Ramón Subercaseaux.

Critics remarked on the young American’s bravura brushwork and unconventional compositions that challenged stuffy academic norms without entirely overturning them.

Carolus-Duran’s influence is evident in Sargent’s daring approach: the use of deep, unmodulated shadow and flickering light, and an emphasis on immediacy over laborious layering. Sargent painted “wet-into-wet” – blending and shaping forms on the canvas in spontaneous strokes – which lent his best portraits a sense of living, breathing presence.

By the late 1870s, Sargent’s emerging alla prima mastery shone in both portraits and genre scenes. One early triumph was The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit (1882), a portrait of four young sisters in Paris that Sargent composed in an unconventional, enigmatic way – with the girls placed informally in a dim, spacious room. The painting, now famous for its haunting atmosphere, showed Sargent’s debt to Velázquez’s Las Meninas in its bold composition and interplay of light and shadow.

Another was El Jaleo (1882), a life-sized depiction of a flamenco dancer performing with musicians, inspired by Sargent’s travels in Spain. When El Jaleo debuted, viewers were stunned by its theatrical lighting and dynamic brushwork: the dancer swirls in white skirts at center while guitarists and onlookers fade into smoky darkness at the edges, an effect of motion and mystery that one contemporary described as making the canvas “a living thing”. These works announced that Sargent could handle not only polished society portraits but also dramatic, genre-defying scenes pulsing with energy.

Sargent’s portrait painting technique by this time was fearless and fluent. Working mainly from live sittings, he would swiftly sketch the pose in charcoal, then attack the canvas with broad brushes, often completing a likeness in far fewer sessions than other portraitists of the day. His swift, unerring brushwork brought out the sheen of satin dresses, the glint of jewelry, the softness of flesh and the sparkle in an eye with astonishing economy of means.

“A portrait is a painting with something wrong with the mouth,” Sargent once joked, acknowledging the notorious difficulty of pleasing his sitters. Indeed, he was a perfectionist who sometimes scraped off and repainted a face multiple times to get it right. But when all went well, the result was a portrait that pulsed with life, capturing not only a subject’s physical appearance but an impression of their personality and mood.

One iconic example is Lady Agnew of Lochnaw (1892), a half-length portrait of a young Scottish aristocrat. Sargent’s relaxed yet regal depiction of Lady Agnew – seated in an upholstered chair, gazing directly at the viewer with a faint smile – combined delicacy and quiet strength in equal measure. The painting’s nuanced color harmony of lavender, ivory, and soft grays and its confident, flowing brushstrokes made it an immediate success, enhancing Sargent’s reputation as the era’s portrait virtuoso.

Scandals and Triumphs: Madame X and Defiance of Society

Photographer unknown, Sargent in his studio with Madame X (1885 CE)

Photographer unknown, Sargent in his studio with Madame X (1885 CE)

At the 1884 Paris Salon, Sargent unveiled a portrait that he hoped would solidify his standing among France’s elite portraitists – a painting officially titled Portrait of Madame Pierre Gautreau but now infamous as “Madame X.” The subject, Virginie Amélie Gautreau, was a young American-born Parisian socialite celebrated for her beauty and eccentric style.

Sargent portrayed her in a sleek black gown with jeweled straps, one strap originally painted slipping provocatively off her shoulder – a pose he felt captured her persona. The reaction was explosive. While Sargent had intended the portrait as a bold but tasteful depiction of modern elegance, many Salon viewers found it shocking and indecent, reading the fallen strap and Virginie’s pale, powdered skin as suggestive and “unbecoming.”

The French critics’ denunciations were scathing: Gautreau was mortified, and Sargent, aghast at the scandal he had unwittingly caused, repainted the strap in its proper place on the shoulder to quell the uproar. It was too late – Paris had made up its mind. “A portrait [of a lady] should show a woman of fashion, not a fallen woman,” sniffed society matrons. Sargent’s clientele in Paris evaporated overnight; the artist later quipped that every time he painted a portrait, he lost a friend. Facing embarrassment and a sudden loss of commissions, the 28-year-old painter retreated to London to rebuild his career.

Ironically, Madame X is now regarded as Sargent’s masterpiece and one of the defining images of the Gilded Age. With its stark contrast of Madame Gautreau’s alabaster skin against a flat bronze background, and her haughty profile turned in perfect silhouette, the painting possesses a timeless allure.

The defiance of society inherent in Sargent’s portrayal – showing a woman with unapologetic poise and sensuality – marked a turning point in portraiture. No longer merely flattering decorations, portraits could be statements of personality and even provocation. As art historian Trevor Fairbrother notes, Sargent “was not a great society painter, he was a great painter who painted society” – imbuing his society portraits with psychological depth and modern style.

Madame X today hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, emblematic of how Sargent captured the glamour and tension of the Gilded Age. In Virginie Gautreau’s raven-black gown and aristocratic pose, one sees both the opulence of haute monde fashion and a hint of the transgressive independence that such women aspired to, foreshadowing changing roles of women in the new century.

London eventually offered Sargent a second act. With help from friends like writer Henry James, who described Sargent as “civilized to his fingertips” and introduced him enthusiastically to British high society, Sargent slowly gained new patrons.

By the late 1880s and 1890s, he was the portrait painter of choice for the wealthy elite on both sides of the Atlantic. His studio on Tite Street in Chelsea (previously occupied by James McNeill Whistler) became a veritable parade of nobility, industrialists, artists, and celebrities sitting for their likenesses.

Among Sargent’s Gilded Age high-society portraiture were portraits of aristocratic women like Lady Gertrude Agnew, Mrs. Isabella Stewart Gardner (1888) – the influential Boston art patron whom Sargent painted as a commanding figure in a white gown – and the Wyndham Sisters (1899), a triple portrait of three elegant sisters dubbed “The Three Graces” by the press.

He painted royals and businessmen, from Mrs. George Swinton (a grand society hostess in London) to the steel magnate Charles Schwab. Each portrait Sargent tailored to its subject and setting: as one observer noted, his English sitters appeared stately, his American sitters exuded a democratic vigor.

Sargent’s keen eye for social nuance meant he often suggested the perfect pose or attire to convey a person’s status and character. This instinct is evident in portraits like Lady Agnew, whose languid pose and direct gaze project modern confidence, or President Theodore Roosevelt (1903), whom Sargent depicted standing assertively, hand on hip, embodying executive authority.

In capturing the spirit of the Gilded Age, Sargent’s portraits go beyond surface opulence. He painted the nouveau riche and old aristocracy with equal insight, from the bejeweled socialites of New York to the patrician Bostonians “with ancestral responsibilities on their shoulders”. His works reflect the era’s contradictions: enormous wealth and refinement paired with underlying social tensions.

In the sumptuous silks and pearls of his female sitters, one senses both the power and the decorative trapping of their roles. Some critics in Sargent’s time and later accused him of being a mere “society painter,” flattering the rich and beautiful for hefty fees. It’s true that by 1900 Sargent was commanding high prices and was courted by high society (one French critic quipped in the early 1880s that “all pretty women dream of being painted by him”). Yet Sargent’s best society portraits have an undercurrent of narrative and realism that sets them apart.

In Madame X, scandal aside, there is an almost clinical study of a persona – she is both glamorous and isolated against that empty backdrop. In The Daughters of Edward D. Boit, the children of a wealthy American family in Paris are rendered not as cherubic dolls but as mysterious, introspective figures scattered in shadowy space, symbolizing perhaps the loneliness of childhood. Sargent’s society portraits, at their finest, became slices of life from the Gilded Age: capturing the surface glitter of an era even as they hint at the personal and cultural complexities beneath.

Beyond Society: Notable Works Outside the Gilded World

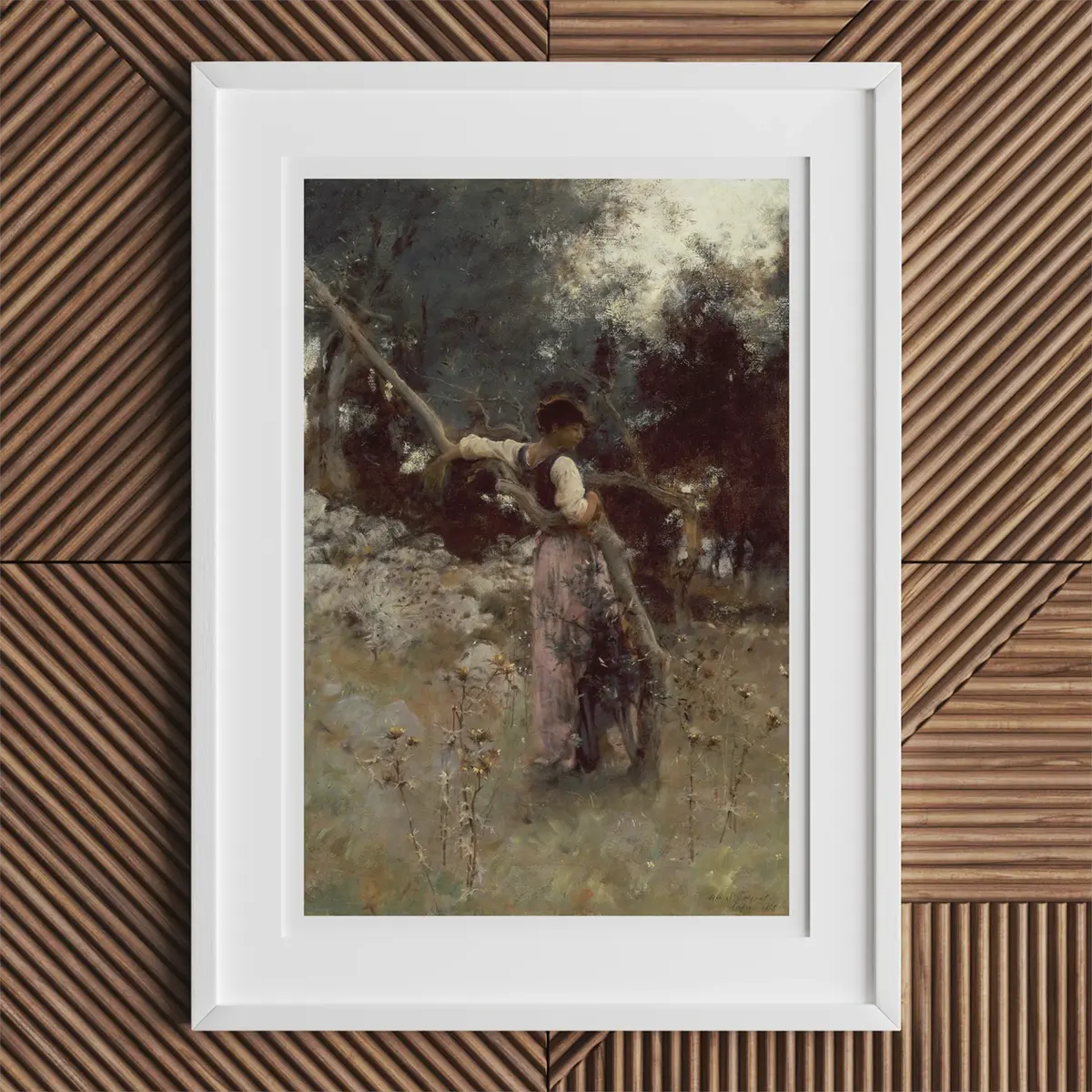

John Singer Sargent, A Capriote (1878 CE)

Though best known in his lifetime for high-society portraits, Sargent’s artistic appetite was far more catholic and insatiable than many realized. He pursued a variety of genres with equal mastery, often during breaks from portrait commissions.

In the late 1870s and early 1880s, he painted landscapes and genre scenes inspired by his travels: Oyster Gatherers of Cancale (1878) depicted peasant girls on a French beach in pearly coastal light, while A Capriote (1878) showed an Italian model lounging in an olive tree, reflecting Sargent’s interest in natural, spontaneous poses.

During a trip to North Africa in 1880, Sargent painted Fumée d’ambre gris (Smoke of Ambergris), an evocative scene of a veiled woman inhaling perfume fumes – a subject tinged with Orientalist fascination and mystery. In Venice, he roamed with sketchbook and brushes, capturing atmospheric views of Venetian canals and architecture not as grand vedute but as intimate, light-dappled studies of everyday life – radically different from the more stagy Venetian scenes of other artists of his day.

These lesser-known works reveal Sargent’s constant experimentation. El Jaleo, mentioned earlier, is one example of him stepping outside polite portraiture to explore music, dance and la vie bohème.

He also painted his friends and fellow artists in informal settings: his friend Robert Louis Stevenson appears lanky and restless, pacing across a carpet in an 1885 portrait that breaks the conventional rules by cutting off part of the subject’s body and placing him off-center. Such creative risks show Sargent engaging with the impressionist and realist currents of his time.

He was acquainted with the Impressionists, too – he visited Monet at Giverny and even purchased Monet’s works. Sargent’s own brushwork and lighting in outdoor scenes like Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose reflect this influence. Yet Sargent never fully abandoned the emphasis on form and drawing he had learned; as the MFA’s biography notes, he didn’t go as far as to dissolve form into pure color patches like Monet did. In effect, he balanced academic technique with impressionist light and color, which gave his non-commissioned works a unique vitality.

Some of Sargent’s intimate studies and sketches remained private during his life, only to surface decades later. He filled sketchbooks with charcoal and pencil drawings of friends, scenes from travels, and studies of the figure.

Especially intriguing are the numerous male nude studies he drew – often rendered in quick, sensitive strokes – which he kept to himself, likely aware that exhibiting such works would court misunderstanding in Victorian times. These drawings, along with informal oil sketches of friends, reveal a more introspective Sargent at work, fascinated by form and human anatomy beyond the confines of polite art.

Sargent once lamented to a friend that portrait painting was confining him, calling it “a pimp’s profession” due to the social games involved in commissions. In his personal time, he sought escape through landscape painting en plein air, experimenting with watercolor, and painting those closest to him without filters.

Mural Commissions: The Triumph of Religion in Public Spaces

John Singer Sargent, Synagogue (1919 CE)

Another arena in which Sargent channeled his prodigious talent was mural painting, on a scale that went far beyond the easel. At the end of the 19th century, Sargent undertook a prestigious public commission that would consume him off and on for nearly thirty years: the murals for the Boston Public Library.

Titled “The Triumph of Religion,” this project was an ambitious cycle intended to adorn the library’s grand staircase and reading room with themed panels blending classical mythology, world religions, and allegory.

Sargent, ever eager to prove his range, threw himself into the task, studying Byzantine mosaics and Renaissance frescoes for inspiration on large-scale composition. Starting in 1890, he designed and executed a series of vast canvases in his London studio and installed them in Boston in stages over the next decades.

The Boston murals reveal yet another facet of Sargent’s abilities. They are symbolically complex and densely populated with figures – prophets, angels, deities, and devils – nothing like the direct portraiture he was known for. In one panel, Frieze of the Prophets, a lineup of ancient Hebrew prophets is depicted in a nearly monochrome, sculptural relief style, conveying gravitas and unity.

In another, The Pagan Gods, colorful figures from pagan mythology recline amidst swirling clouds. The centerpiece, Dogma of the Redemption, featured a luminous Christ figure and was so controversial for its depiction of Jews (a subject of critique and even defacement) that parts of the series were eventually removed or relocated.

Sargent tackled themes of faith, doubt, and modernity in these works, if not entirely successfully, then at least with earnest intellectual effort. Technically, the murals marry his academic precision – drawing on the model, careful planning of poses – with a more experimental spirit, including some modernist touches in abstract pattern and color. They forced Sargent to think on an epic narrative scale, synchronizing multiple figures and gestures into a coherent design across architectural space.

Though initially met with mixed reviews, the Boston murals stand today as a testament to Sargent’s dedication to expanding his artistic horizons. Not content to be pigeonholed as a portraitist, he essentially taught himself the art of mural painting in middle age, producing works that still adorn the library and inspire viewers to look upward in awe.

The Triumph of Religion murals have in recent times been reappraised, with scholars finding in them layers of meaning and an insight into Sargent’s own spiritual contemplations. They explore the clash and convergence of cultures – fitting for an expatriate who straddled worlds – and perhaps subtly comment on the waning of traditional faith in a modern, scientific age.

Sargent also completed a second major mural project in Boston: the rotunda of the Museum of Fine Arts, for which he painted classical gods and muses (and where Thomas McKeller’s body served as a model for many figures). These public works further cemented Sargent’s legacy in the city of his forebears, linking his name to the American Renaissance movement that sought to elevate public spaces with high art.

Artistic Travels: From the Middle East to Venice

John Singer Sargent, Bedouins (1905-06 CE)

John Singer Sargent, Bedouins (1905-06 CE)

Restless at heart, Sargent was a traveler for the ages, and his extensive journeys played an essential role in shaping his stylistic evolution. He once remarked that he could “never be tied down to one place – I must keep moving.” Indeed, when not tethered to his studio for commissions, he sought new vistas almost compulsively.

In the 1880s and ’90s, he crisscrossed Europe and ventured to the Middle East, often in the company of artist friends. These travels yielded a rich harvest of watercolors and oils that reveal Sargent’s delight in other cultures and landscapes.

In 1890, Sargent traveled to the Middle East and North Africa, visiting locales like Cairo, Jerusalem, Damascus, and Tangier. Rather than creating sweeping Orientalist fantasias as some contemporaries did, Sargent’s paintings from these trips are marked by keen observation and respect for detail.

His watercolor Bedouins (1905–06) presents two Bedouin men in traditional robes with a direct, unsentimental eye – the textures of their garments and the play of desert light captured with vibrant washes of color. His Middle Eastern street scenes and market sketches show a fascination with everyday life: the bustle of a bazaar, the silhouette of a mosque at sunset, the posture of a camel driver resting in the shade.

Sargent’s transnational perspective was ahead of its time, resisting reductive exoticism. As one critic notes, his portrayals of “the other” often eschewed stereotypes, aiming instead for authenticity in depicting foreign places.

Venice was another enduring love of Sargent’s. He visited repeatedly, not to paint the cliched Grand Canal vistas but to capture intimate corners of Venetian life: a shaded courtyard with laundry hanging, a glint of sunlight in a narrow canal, local men gossiping in a café. He worked in watercolor and oil, producing dozens of Venetian scenes that range from the lyrical to the moody.

These Venetian works, often done en plein air, have an almost snapshot quality – as if Sargent’s roving eye and quick hand were taking visual notes of fleeting impressions. They also allowed him to play with pure visual elements like reflections on water, the crumbling textures of brick and stone, and the ever-shifting Mediterranean light. In paintings like The Steps of the Palazzo Foscari or Street in Venice (both c. 1882), Sargent’s colorful, impressionistic strokes celebrate the beauty of ordinary moments in a historic city, bridging realism and impressionism.

Sargent’s travels were not confined to Europe and the Near East. He made multiple trips to the United States as well, particularly after 1900. In the Rocky Mountains of Montana, in the sunny orange groves of Florida, and in the forests of Maine, he found fresh inspiration. He painted fisherfolk on the shore in Florida, shimmering alpine lakes in the Canadian Rockies, and the rugged grandeur of the Western frontiers. These experiences further broadened his visual repertoire, confirming him as a global artist whose oeuvre mapped a rapidly changing world.

Perhaps the most significant artistic expedition Sargent undertook was a months-long journey to Spain and North Africa in 1912, specifically to study the art and architecture of the Islamic world. This trip culminated in one of his last great series of oils, the Arabian or Syrian paintings, where Sargent depicted Bedouin camps, Arab women, and architectural studies of mosques. These works remained mostly in his possession, not widely exhibited – they were personal exercises in seeing and recording.

When viewed together, Sargent’s travel paintings form a kaleidoscopic portrait of a world in motion: from the languid canals of Venice to the bright snows of the Alps, from Spanish dance halls to Middle Eastern deserts. Through these, we glimpse Sargent the adventurer and observer, the artist-as-wanderer who found renewal in each new horizon.

A Shift to Freedom: Sargent's Later Career in Watercolors

John Singer Sargent, Sketch of Cellini's "Perseus" (1909-10 CE)

By the turn of the 20th century, Sargent had grown weary of the ceaseless parade of portrait commissions. The pressures of pleasing wealthy patrons and the formulaic social rituals involved began to chafe at his creative spirit.

In 1907, at the height of his fame, Sargent made a bold decision to stop painting oil portraits on commission. “No more paughtraits,” he declared to friends in his witty, French-accented English. Though he did not abandon portraiture entirely, he henceforth accepted sitters mostly on a friendship basis and turned his primary focus to other subjects – especially watercolor landscapes.

This marked a late-career liberation for Sargent. Watercolor, a medium in which his mother had tutored him as a child, became his new passion. Between 1900 and his death in 1925, Sargent produced hundreds of watercolors, traveling with paper and paint box to capture spontaneous impressions of nature. Working outdoors, often in the company of his sister Emily and friends, he painted sun-drenched scenes that are among the most joyful and unrestrained of his works.

His watercolors feature everything from Alpine avalanches of rock to delicate floral close-ups. In the mountains, he painted sparkling streams, craggy granite faces, and his companions lounging in wildflower meadows. In Mediterranean locales, he painted marble statues in gardens, white sails on turquoise seas, and orange trees laden with fruit. T

he vibrant palette and swift execution of these pieces show Sargent reveling in the spontaneity the medium allowed. Unlike his staged studio portraits, en plein air watercolor demanded immediate response to changing light and conditions – a challenge Sargent embraced.

Critics were astonished by the vigor of Sargent’s watercolors when they were first exhibited. A 1909 show of his watercolors in New York sold out almost immediately, with the Brooklyn Museum purchasing a large group in its entirety. Reviewers praised how these works seemed to “breathe” with fresh air and painterly freedom. One noted that “Sargent throws color on paper with the riotous delight of a child splashing in mud puddles, yet the results are masterly” – an indication of how his technical control never waned even as his style loosened.

In watercolors like Simplon Pass: The Green Parasol (c. 1911), depicting women sketching under a vivid green umbrella in the Alps, Sargent’s brush dances across the paper, balancing broad translucent washes with fine details achieved through wax resist and drybrush.

The medium allowed him to be intimate and experimental, capturing fleeting effects of dappled light and reflections that might be difficult in oil. By stepping outside the formal confines of portrait commissions, Sargent reconnected with the simple pleasure of painting for himself.

Sargent could not entirely escape portraiture’s pull. He continued to create charcoal portrait sketches, often in a single sitting, as a compromise to satisfy occasional demands. These charcoals, of figures like diplomat Otto von Bismarck or art critic Roger Fry, are today considered masterpieces of drawing – bold, elegant monochrome images that distill character in a few sweeping lines and smudges.

On special request, Sargent did paint a few more oils of friends in these later years, like his moving 1913 portrait of his friend Sybil Sassoon in profile, or his tender 1916 portrait of Henry James towards the end of the novelist’s life. But largely, after 1907, Sargent devoted himself to the landscape and figure studies he loved, finding in nature and travel the rejuvenation that society portraiture no longer provided.

Hidden Narratives: Sexuality and an Enigmatic Life

John Singer Sargent, Man Wearing Laurels (1874-80 CE)

John Singer Sargent, Man Wearing Laurels (1874-80 CE)

Behind Sargent’s glossy professional image as society’s portraitist lay a private life that has intrigued – and eluded – biographers. Sargent never married and left behind scant personal correspondence, so clues to his inner world emerge largely from anecdotes and, most tantalizingly, from his art. Over the years, scholars have increasingly explored themes of gender and sexuality in Sargent’s work, uncovering hidden narratives that contrast with the conventionality of his public portrait oeuvre.

One major revelation came in the 1980s, when a trove of Sargent’s previously unseen drawings of nude male models was exhibited for the first time. These drawings – many of them frankly sensual, showing male figures in reclining or vulnerable poses – sparked a reevaluation of Sargent as not just a genteel society painter but a man with unconventional desires and friendships.

Whispers about Sargent’s sexuality had circulated before — he moved in artistic circles that included gay figures like Oscar Wilde, and his closest lifelong friends were primarily men. But now there was tangible evidence that Sargent found the male form deeply compelling and worthy of study in a private, expressive context.

While Sargent did not openly identify as anything (the term “gay” as an orientation was not used in his time), many interpret these works as indicative that he was likely homosexual or bisexual. However, because he was exceedingly discreet – perhaps out of necessity in an era when homosexuality was criminalized – the question of Sargent’s romantic life remains partly speculative. Was Sargent gay, bisexual, or simply a man whose closest relationships happened to be with men? The truth may never be fully known.

What is documented is that Sargent had intense, meaningful relationships with several men who often served as his muses or models. One was the Italian model Nicola d’Inverno, who worked as Sargent’s studio assistant for years and appears in some of his sketches and paintings. Another was the British artist Albert de Belleroche, whom Sargent painted and traveled with; they were so close that contemporaries jokingly referred to Belleroche as “Mrs. Sargent.” And perhaps most poignantly, there was Thomas McKeller, a young Black elevator attendant whom Sargent met in Boston around 1916 and hired as a model.

McKeller posed nude for many of the figures (both male and female allegories) in Sargent’s grand murals for the Boston Public Library and Museum of Fine Arts. Sargent even painted a private full-length nude portrait of McKeller, a striking image of the model seated on a green cushion with spectral bluish wings behind him, like a fallen angel. This painting, never exhibited in Sargent’s lifetime, was essentially hidden away – Sargent gave the canvas to Isabella Stewart Gardner, perhaps to ensure it was preserved yet kept discreetly in her museum.

Not until decades after Sargent’s death was McKeller’s role acknowledged; for years, the Black man whose form became the basis for Sargent’s painted gods and heroes remained unnamed in the artworks, a silence that speaks to the racial and social dynamics of the time. The exhibition Boston’s Apollo: Thomas McKeller and John Singer Sargent (2020) finally shone light on their collaboration, raising questions about power, visibility, and the personal connection between the patrician artist and his working-class model.

Sargent’s close friendship with Henry James is also worth noting as part of his private narrative. The two men, both American expats of nearly the same age, shared a deep understanding. James often wrote of Sargent’s work, praising its sophistication, and Sargent in turn painted James’s portrait with a psychological acuity that suggests real affection. Some scholars have wondered if their bond contained an unspoken emotional intimacy.

When Henry James died in 1916, Sargent was distraught; he designed James’s memorial plaque for Westminster Abbey, pouring his grief into a final artistic tribute. Whether or not Sargent experienced conventional romantic love, he clearly formed profound emotional attachments that fueled his creativity.

Sargent's many portraits of strong, charismatic women – from diva Elizabeth “Bessie” Marbury to intellectual Vernon Lee (Violet Paget) – also reflect an ease with independent female company. In an era when gender roles were rigid, Sargent seemed to navigate his own path, surrounding himself with a cosmopolitan circle that embraced artistic identity over conformity.

Ultimately, the hidden Sargent that emerges from these facets is a far more complex figure than the elegant society painter stereotype. He was a private individual who guarded his inner life, yet his art leaves clues: the androgynous beauty of some of his nude sketches, the empathy in his portraits of outsiders and creatives, the lifelong aversion to marriage and conventional domesticity.

Today, LGBTQ historians celebrate Sargent as part of a queer artistic lineage, noting that his same-sex interests and gender nonconformity in art were quietly radical for his time. Meanwhile, the story of Thomas McKeller has prompted discussions about how a Black model’s contribution to American art could remain erased for so long – and how Sargent’s own legacy is intertwined with questions of race and representation that are only now being fully explored.

The layers of secrecy and revelation in Sargent’s life add a poignant dimension to our understanding of his paintings, reminding us that art often carries unspoken stories beneath its surface.

Re-Evaluating Sargent: Legacy and Modern Perspectives

J E Purdy, Portrait of John Singer Sargent (1920 CE)

J E Purdy, Portrait of John Singer Sargent (1920 CE)

John Singer Sargent died in April 1925 in London, just shy of his 70th birthday, leaving behind an enormous body of work – roughly 900 oil paintings and over 2,000 watercolors as well as countless sketches. His passing was marked by major memorial exhibitions in Boston, New York, and London. Yet for a substantial part of the 20th century, Sargent’s reputation fell into a peculiar eclipse.

The rise of Modernism in art – with its abstraction and rejection of traditional realism – rendered Sargent’s lush portraits unfashionable to many critics. By the 1950s, some dismissed him as a mere society decorator, technically adept but devoid of deeper significance. The grand manner portrait style he excelled in was considered anachronistic in an era that championed Picasso and Pollock.

However, starting in the late 20th century, a revival of interest in Sargent gained momentum. Art historians and the public alike began to reassess his contribution, recognizing the extraordinary technical brilliance and subtle complexity of his work. Major retrospectives in the 1980s and 1990s (such as a blockbuster 1986 exhibition that traveled from the Tate to the Metropolitan Museum) reintroduced Sargent to new generations.

Critics came to appreciate that beneath the surface elegance of his paintings, Sargent had been quietly pushing boundaries – in gender roles, in cultural perspective, and in the very language of paint. His portrayals of women like Lady Agnew or Mrs. Gardner were now seen as celebrating female self-possession and intelligence, not just beauty. His inclusion of marginalized figures – the Spanish gypsy dancers of El Jaleo, the Bedouin subjects, the black model McKeller – was highlighted as evidence of a broader humanism in his art than he had been credited for.

The late-century discovery and exhibition of Sargent’s male nude drawings (as discussed) also added significantly to this reevaluation. In light of these, Sargent’s work has been examined through the lens of LGBTQ history and postcolonial critique.

Scholars like Trevor Fairbrother and Richard Ormond have published studies revealing the layers of meaning in Sargent’s oeuvre – from the way his paintings negotiate issues of race and empire e.g., the power dynamics in using a black model for white god figures, to how his friendship with Henry James and others hint at a network of queer creativity that has often gone unspoken.

As one biographer put it, Sargent’s life and art encompassed “the full spectrum of human experience – from the opulence of aristocracy to the raw, unfiltered beauty of ordinary life”. Such a scope is now celebrated as ahead of its time, bridging the gap between traditional art and modern themes.

Today, John Singer Sargent is firmly ensconced in the pantheon of great artists. His paintings are centerpieces in museum collections worldwide, admired by casual viewers and connoisseurs alike. He is often cited as “the leading portrait painter of his generation”, a label originally bestowed for his evocations of Edwardian-era luxury in portraits.

He is appreciated as a virtuoso who mastered light and brushwork like few others in history – an American Monet with the drawing skills of an Old Master, as one critic described. Contemporary portrait painters look to Sargent for lessons in capturing the living essence of a subject, while watercolorists study his technique for its boldness and fluidity.

Importantly, the conversations around Sargent have become more nuanced. There is an understanding that the same artist who painted Madame X – icon of elegance – also painted Gassed – indictment of war’s brutality – and drew loving sketches of male nudes, and painted austere prophets on a ceiling. Each of these informs the other, composing a portrait of Sargent himself that is as faceted and rich as the era he lived in.

In the end, Sargent’s legacy may be best summed up by his ability to capture an era’s spirit in vivid detail while simultaneously transcending it. He was both of the Gilded Age and beyond it. As an expatriate American in Europe, he had an outsider’s sharp eye for society’s pageantry; as a sensitive soul with secrets, he imbued his art with empathy and intrigue.

His lifelong wanderlust and curiosity kept his art from stagnating – he kept exploring new subjects, new places, new methods. And through it all, he maintained a standard of craftsmanship that commands awe. More than century after his death, viewers still find themselves drawn into the nuanced interplay of opulence and fragility in Sargent’s work– be it the shimmering satin of a gown that cannot hide a sitter’s melancholy, or the golden glow of a lantern illuminating a child’s face at dusk.

Sargent invites us to look closer and see beyond the surface. In doing so, he left an indelible impression on the canvas of art history, one that continues to inspire and captivate with its narrative depth and visual poetry.

Reading List

- Bedouins - Brooklyn Museum

- El Jaleo - Wikipedia

- How Henry James's Family Tried to Keep Him in the Closet - Colm Tóibín in The Guardian

- John Singer Sargent - The Metropolitan Museum

- Lady Agnew of Lochnaw - Wikipedia

- Madame X - Lumen Learning

- New Interpretations of Sargent's Murals - Boston Public Library

- Nude Males in Drawing - Wikipedia

- Portrait of Madame X - Wikipedia

- Sargent and Spain - National Gallery of Art

- Sargent, Soul Mate to Henry James - Deborah Wiesgall in the [New York Times

- The Hidden Sargent - Patricia Failing in ARTnews

- Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian History - Michael J. Murphy

- Why Madame X Scandalized the Art World - Alina Cohen on Artsy