Exploring the Impact of Famous Collage Artists Who Defined the Artform: Dada to Feminism, the Harlem Renaissance, Matisse's 'Drawings with Scissors' and More…

Collage is not the art of cut and paste. It is the seduction of disruption. The poetry of paper sliced mid-thought, reassembled into defiance. It arrived not from the loins of modernism but centuries earlier—inked onto scrolls in 10th-century Japan, sewn into devotional fragments, hiding in plain sight. But don’t worry: Wikipedia already tripped over that rabbit hole. And plenty of others.

The artists gathered here—eleven shape-shifters with scissors for tongues—didn’t simply use collage. They seduced it. Shattered it. Laughed at it. Turned it inside out. Summoning its strange possibilities into new dimensions of beauty, queerness, satire, rage, seduction, protest. They didn’t define collage as much as they exploded its entrails across the walls of politics, the flesh of feminism, the afterbeats of jazz and Weimar smoke.

We must, regretfully, address the definition of the definition. No, that wasn’t a typo. You live in a world where art historians kneel at the pews of Tate and Guggenheim, so you’ve heard the gospel: that modern collage began with Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque circa 1912, when they started glueing fake wood grain and newspaper scraps into their cubist works. Papier collé. Or, as I like to call it, artisanal sticker-shock.

But let’s be honest. Their early collages? Not their finest. Even Picasso, patron saint of ego, wouldn’t post “Bottle of Vieux Marc” to his Instagram. No, these works survived because they were birthed by names that could bully permanence into history. Not because they were glorious. And yet—they are important. Not for perfection, but for permission. They cracked open the frame. They let the wrong things in. They made room for what came next.

That’s the real gift of those janky little cubist experiments: they marked the moment collage stopped being ornamental and started being philosophical. They whispered (okay, shouted): Art is no longer bound by brush or bronze or marble. Anything that can be taken apart can be made sacred.

Each of the eleven artists in this list brought collage to a new frontier. Political. Personal. Spiritual. Ugly. Dazzling. They built mythologies out of clippings. They turned scraps into sermons. They hacked history with a glue stick. And here, then, is your invitation to the scissors’ revolution.

You’re about to meet:

-

A Dadaist who sliced patriarchy with kitchen knives.

-

A Harlem artist who chorused Black identity into layered refrains.

-

A Frenchman who drew with scissors in his final decade and made the paper sing.

-

A feminist typographer who commandeered mass media and made it scream back.

-

And me? I’m a collage artist too. Or a thief. Or a mirrorball. I cut up the internet and reassemble its shards into confessions. And I’ll admit: writing this, I didn’t know them all. Not at first. Maybe you won’t either. That’s the point. The paper trail is long. The archive is crooked. Let’s follow it anyway. Just don’t expect it to be linear. Expect it to bleed.

Famous Collage Artists Who Defined the Artform

1

Hannah Höch

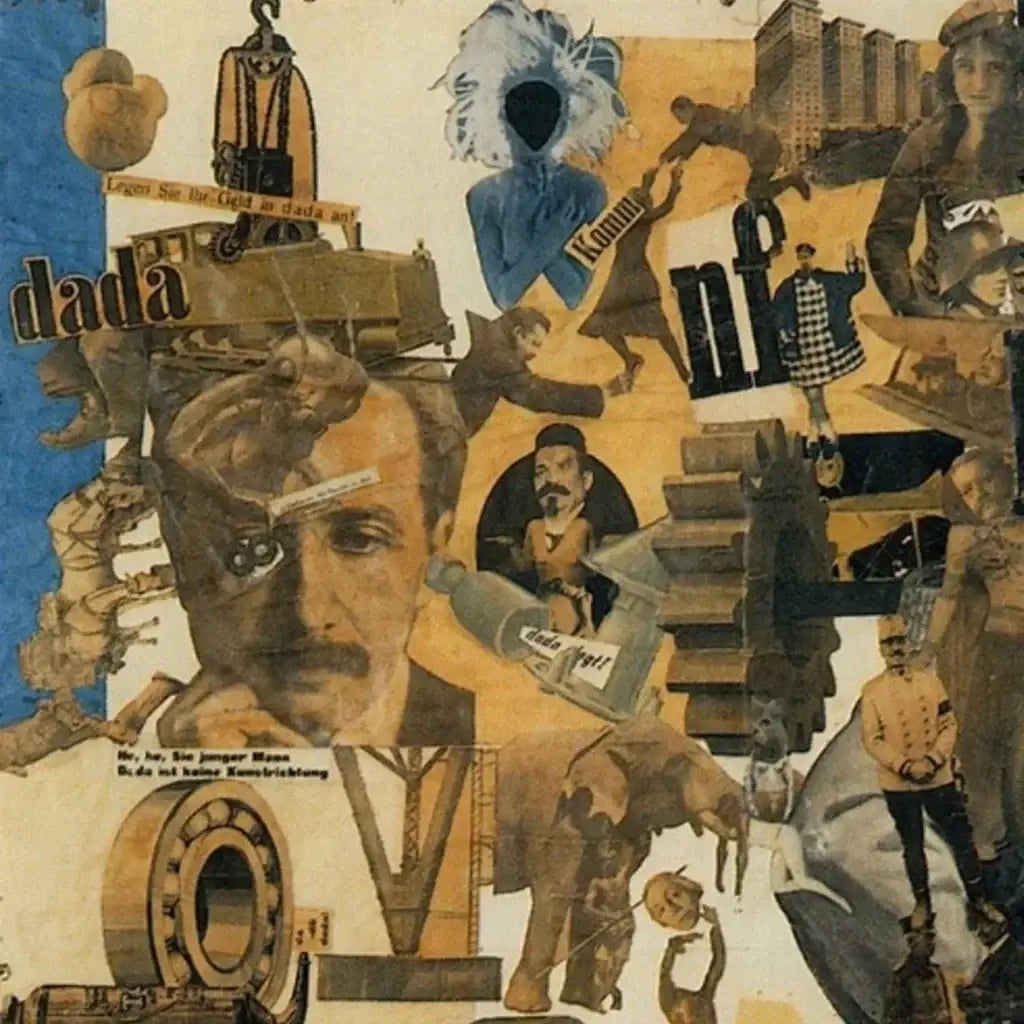

Hannah Höch, Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany, 1919. Collage. 44 9/10 × 35 2/5 in | 114 × 90 cm.

...

Photomontage Pioneer. Political Saboteur. Visual Anarchist.

Hannah Höch didn’t cut with safety scissors. She wielded the blade like a scalpel, dissecting the cultural corpse of Weimar Germany and stitching it back together with wire, wit, and weaponized absurdity. Born in 1889 in Gotha and sharpened in the experimental furnace of Berlin’s pre-war avant-garde, Höch fused trained craftsmanship with radical disobedience.

A graduate of the Berlin College of Arts and Crafts and the Royal Museum of Applied Arts, Höch entered the arts as a graphic designer for women’s magazines. But she wasn’t interested in pretty things. She was interested in blowing up the ideology of pretty. Collage wasn’t her medium—it was her mode of resistance.

She was the lone woman in a Dada boys’ club.

A movement drenched in nihilism and cabaret smoke, where chaos was both content and creed. Among male peers like Raoul Hausmann and George Grosz, Höch stood her ground and sliced deeper. Her work wasn't just anti-authoritarian; it was anti-patriarchal, anti-nationalist, anti-aesthetic. She fought fascism with found imagery. Her materials were stolen from newspapers, fashion pages, mail-order catalogues, and war-time propaganda—visual refuse transformed into razor-sharp satire.

Her seminal work?

Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany (1919):

-

A sprawling, feverish photomontage nearly four feet tall

-

Choked with politicians, automatons, cabaret performers, and dismembered machinery

-

Organized like a battlefield—chaos staged with precision, commentary dressed as collage

Through this work, Höch took apart the bloated masculinity of Weimar politics and rebuilt a world teetering between progress and oblivion. The title alone is a provocation—the “kitchen knife” slashing through the “beer belly” of bloated empire. It’s both domestic tool and political blade.

Major Themes in Höch’s Work:

-

The “New Woman” as both subject and site of cultural anxiety

-

Collage as a critique of mass media and gender roles

-

Humor and grotesquerie as visual strategy

Branded degenerate by the Nazis, Höch went underground. She survived WWII in quiet defiance, preserving her practice in shadow while the world burned around her. Her influence radiates through later generations—from Barbara Kruger to Cindy Sherman, from punk zines to feminist meme culture.

Höch didn’t seek to document reality. She dismantled it. She made photomontage not just a tool of expression but a blueprint for ideological sabotage. What she cut, she remade—sharp, funny, furious, unforgettable.

Reading List

- Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife on Smart History

- Hannah Hoch on The Art Story

- Hannah Hoch on Encycolpedia.com

- Hannah Hoch on Wikipedia

2

Romare Bearden

Romare Bearden, Empress of the Blues, 1974, acrylic and pencil on paper and printed paper on paperboard, 36 x 48 in. (91.4 x 121.9 cm.)

...

Harlem’s Storyteller. Jazz’s Visual Twin. America’s Collage Griot.

Romare Bearden didn’t paint scenes—he reconstructed them from memory, sound, and the fractured syntax of lived experience. Born in Charlotte, North Carolina in 1911 and raised amid the twin pulses of Pittsburgh steel and Harlem heat, Bearden was fluent in collage long before he ever touched a pair of scissors. Migration, jazz, and ancestral longing were already layered within him. What he did with paper and pigment was simply a method of excavation.

Educated at Boston University, NYU, and Columbia—where he studied under George Grosz—Bearden cultivated a visual language that refused to separate the personal from the political. As a Black man working in 20th-century America, he didn’t paint abstractions of struggle. He painted its architecture—porches, city blocks, baptismal pools, brass bands, domestic rituals—all kaleidoscoped into fierce, prismatic compositions.

Key Materials and Techniques:

-

Printed paper, fabric, acrylic, graphite

-

Overlapping silhouettes, rhythmic layering

-

Juxtapositions evoking improvisation and narrative compression

In works like Empress of the Blues (1974), you don’t just see a woman. You hear her. She moans from the paper’s grain, shoulders squared with grace and fatigue. Bearden’s collages hum with Afro-Atlantic spiritual density—a Southern church service spliced with subway static and trumpet calls. Every surface is crowded, not with clutter, but with history.

Major Themes:

-

Memory as communal inheritance

-

The Black American South and Northern urban diaspora

-

Jazz structure applied to visual composition

Raised in a Harlem home that became a salon for thinkers and artists—from W.E.B. Du Bois to Langston Hughes—Bearden witnessed the Harlem Renaissance not from the outside but from the parlor. He didn’t just inherit its legacy; he stretched it into the next century.

Bearden’s collage technique echoed the pulse of improvisational music. He worked like a jazz musician: repetition with variation, syncopated cuts, visual riffs across a single theme. He often said, “I try to show that when some things are taken out of context, they can still speak a truth.” He was speaking of photographs. He was speaking of people.

Legacy Beyond the Canvas:

-

1964: Appointed first art director of the Harlem Cultural Council

-

Co-founded Cinque Gallery and The Studio Museum in Harlem

-

Collaborated on set designs for Alvin Ailey’s American Dance Theater

-

Illustrated books, wrote plays, composed music

The Romare Bearden Foundation, founded in 1990, continues to support artists and scholars in his name. But his true afterlife lives in every artist who collages from chaos, who dares to build coherence from fracture. Bearden didn’t depict Harlem. He translated it. His works are not portraits. They’re spiritual blueprints—layered, sonic, fiercely alive.

Reading List

- Empress of the Blues in American Art

- Harlem Renaissance on History.com

- Romare Bearden on Biography.com

- Romare Bearden on Brittanica.com

- Romare Bearden on Encyclopedia.com

- Romare Bearden on Holmes Art Gallery

- The Romare Bearden Foundation

3

Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse, Zulma, 1950. Gouache on paper. 108 x 60 inches.

...

Scissors in Hand. Color Unleashed. Art Reborn.

Henri Matisse didn’t fade quietly into old age. He ignited. When illness made painting arduous, he stood defiant—with shears in one hand and chromatic thunder in the other. His late-life works, the famed cut-outs, weren’t a farewell. They were a second adolescence. A riot of color born from paper, not pigment. He called it “drawing with scissors,” but what he really did was orchestrate color into motion.

In the 1940s, Matisse retreated to Vence in the south of France, body weakened but vision sharpened. Unable to stand at an easel, he turned to gouache-painted sheets and began slicing. The process was tactile, immediate—liberated from the long rituals of oils and brushes. It was collage, yes, but it moved with the logic of dance and the boldness of stained glass.

Why It Changed Everything:

-

Forged a new medium using scissors, gouache, and intuition

-

Rejected line in favor of color as structure

-

Expanded abstraction while rooting it in organic form

Zulma (1950) is no still life. It’s a monument to sensual rhythm—standing 108 inches tall, cut into shimmering planes of color, stitched together like a hymn. The figure is reduced but intensified, shaped from confidence and curve. Matisse wasn’t editing the body. He was distilling it.

Core Themes in the Cut-Outs:

-

Movement over representation

-

Joy as resistance

-

Nature reimagined through paper and breath

These weren’t sketches—they were final statements. Each pinned piece was alive with possibility, evolving on studio walls like butterflies mid-transformation. The logistics of preserving them later became an art form in itself. Conservationists today still chase the ghost of his original compositions, pinned with straight edges and quiet urgency.

And yet, these pieces feel timeless. Matisse’s cut-outs would influence everything from modern illustration and advertising to fashion editorials and contemporary abstract painting. They arrived at a moment when the art world thirsted for theory and got, instead, ecstasy.

Matisse died in 1954. But in those final years, he remade modernism from a wheelchair—with scissors, pinned paper, and a belief that art could still astonish. Not despite limitations. But because of them.

Reading List

- henrimatisse.org

- Henri Matisse cut-outs on Wikipedia

- Henri Matisse cut-outs on moma.org - exhibition

- Henri Matisse cut-outs on moma.org - process

- Henri Matisse cut-outs on Wide Walls

- Henri Matisse cut-outs on YouTube

- Henri Matisse creating one of his cutouts

- How Matisse's cut-outs took over the illustration world

- How to Read a Matisse - The Met

- Conserving the Swimming Pool

- Zulma on moma.org

4

Barbara Kruger

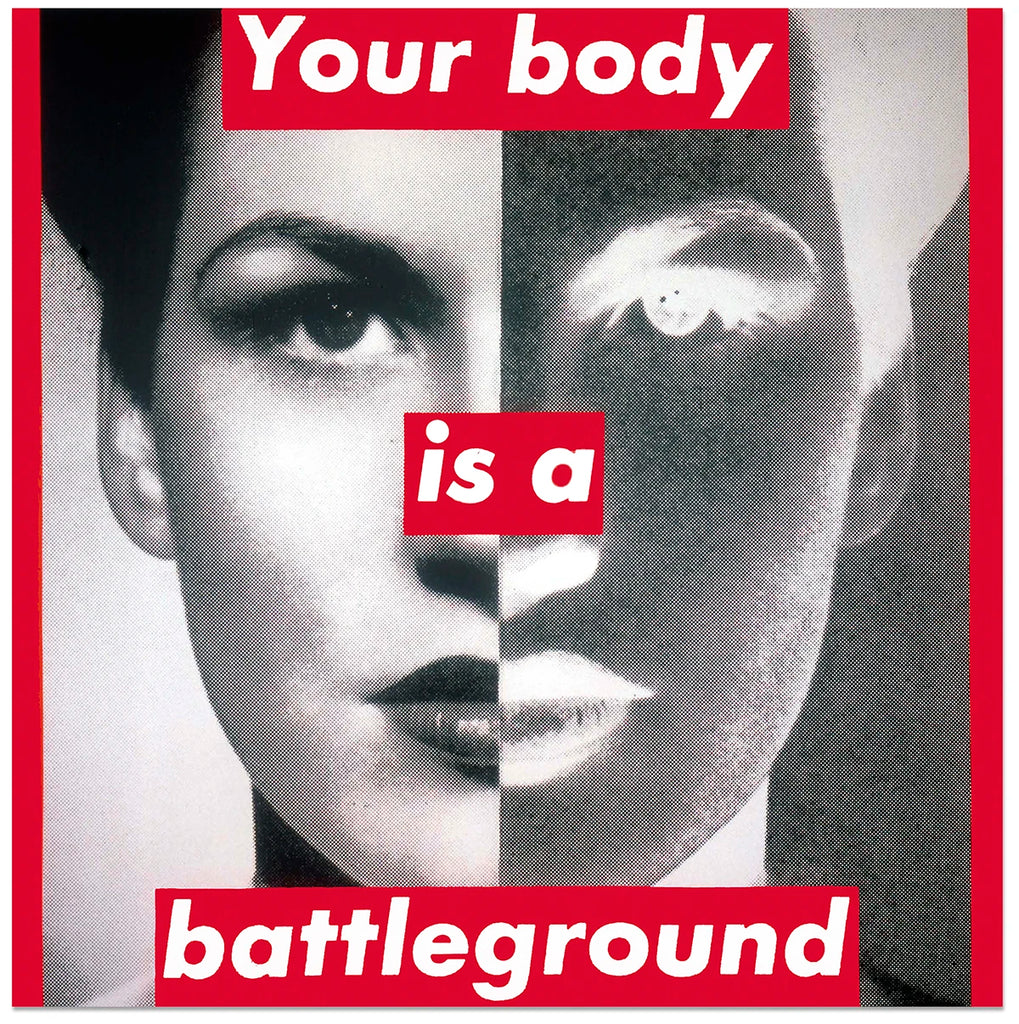

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Your Body is a Battleground), 1989. Photographic silkscreen on vinyl. 112 x 112 in. (284.48 x 284.48 cm).

...

Typography’s Guerilla General

Barbara Kruger doesn’t ask questions. She interrupts them. Her work lands like a billboard in the brain—declarative, dissecting, demanding. Blending mass media with conceptual fury, Kruger transformed the flat language of advertising into a site of feminist insurgency.

Born in 1945 in Newark, New Jersey, she was raised on the twin screens of Catholic guilt and American television. After studying at Syracuse and Parsons, Kruger landed at Mademoiselle magazine, where she swiftly rose to become chief designer. She understood visual seduction because she built it—kerning power into commodity and back again.

But something snapped. She took that knowledge and reversed the current. Instead of feeding capitalism’s hungers, she starved it—with appropriation, contradiction, and fierce red overlays.

Signature Style:

-

Black-and-white photographs

-

Overlaid white-on-red Futura Bold Oblique or Helvetica Ultra Condensed

-

Short, blistering phrases that read like accusations—or confessions

Kruger’s aesthetic—once seen, never forgotten—is more than design. It’s confrontation. Her art interrogates the weaponry of language and the architecture of desire. And it does so in giant, public formats: museum walls, bus stops, magazine pages, subway platforms.

Famous Works That Burned Through the Canon:

-

Untitled (Your Body is a Battleground) (1989):

A woman’s face split in stark symmetry—halved between photographic clarity and negative exposure. Over it, the phrase: “Your body is a battleground.” Created in response to anti-abortion legislation, the image became protest placard, feminist manifesto, and cultural litmus test in one blow. -

Untitled (I Shop Therefore I Am) (1987):

A credit card clutched like a dagger. A consumerist creed turned existential crisis. Kruger didn’t just critique capitalism—she exposed it as theology.

Core Themes Across Her Oeuvre:

-

Identity and gender as constructs

-

The psychological violence of media

-

The blurred border between critique and complicity

Kruger's work draws from feminist film theory, structuralism, and postmodern philosophy—but never at the expense of legibility. Her work isn’t for the initiated. It’s for anyone with a gaze and a gut. She doesn’t make you decode. She makes you choose.

Long-Term Impact:

-

A foundational voice in the Pictures Generation

-

Influenced generations of activists, designers, and conceptual artists

-

Continues to create large-scale installations across the globe, from museums to outdoor architecture

Barbara Kruger’s brilliance lies in compression. She distills whole ideologies into four-word ruptures. Her work doesn’t whisper through gallery halls. It shouts from the scaffolding of culture itself—then asks why we were so quiet before.

Reading List

- Barbara Kruger in her own words

- Barbara Kruger on Artland

- Barbara Kruger on The Broad

- Barbara Kruger on jwa.org

- Barbara Kruger on moma.org

-

Barbara Kruger on Wikipedia

- Untitled (I Shop Therefore I Am)

- Untitled (Your Body is a Battleground) on The Broad

- The history of Untitled (Your Body is a Battleground)

5

Robert Rauschenberg

Robert Rauschenberg, Buffalo II, 1964. Oil and silkscreen ink on canvas

96 x 72 in. (243.8 x 183.8 cm.).

...

Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008) was an American painter and graphic artist known for his "combine" works, which blurred the distinctions between painting and sculpture by incorporating everyday objects as art materials. He studied art at the Kansas City Art Institute, Academie Julian in Paris, and Black Mountain College in North Carolina before moving to New York City in 1949.

Rauschenberg's combines integrated discarded objects he collected from the streets of New York City, such as newspaper clippings, photographs, and found objects. He believed that using real-world materials made his art more relatable and reflective of reality. Some of his early works anticipated the Pop art movement, and he is celebrated as a forerunner for nearly every art movement since Abstract Expressionism.

Robert Rauschenberg's contributions to the art world were significant and transformative. He was a primary figure during the 1950s and 1960s and became recognized as a major forerunner of American Pop art, alongside contemporaries like Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns. Rauschenberg's innovative approaches, seen in works like Monogram, expanded the traditional boundaries of art. Opening up new avenues of exploration for future artists.

His "combine" works blurred the distinctions between painting and sculpture, incorporating everyday objects as art materials and challenging the status quo. Rauschenberg's art practice and creative energy was never going to fit into preconceived boxes. Art historian Branden W. Joseph noted that Rauschenberg's work served as a stimulus, an impetus, and a challenge for artists across the board.

Throughout his career, Rauschenberg worked in various mediums, including painting, sculpture, prints, photography, and performance. He collaborated with choreographers like Merce Cunningham, Paul Taylor, and Trisha Brown, and was a founding member of the innovative group Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) in 1966.

Rauschenberg's groundbreaking approach and creative energy had a lasting influence on generations of artists. Hear how Rauschenberg "rewrote the rules of the game" from his son, photographer Chris Rauschenberg.

6

Kurt Schwitters

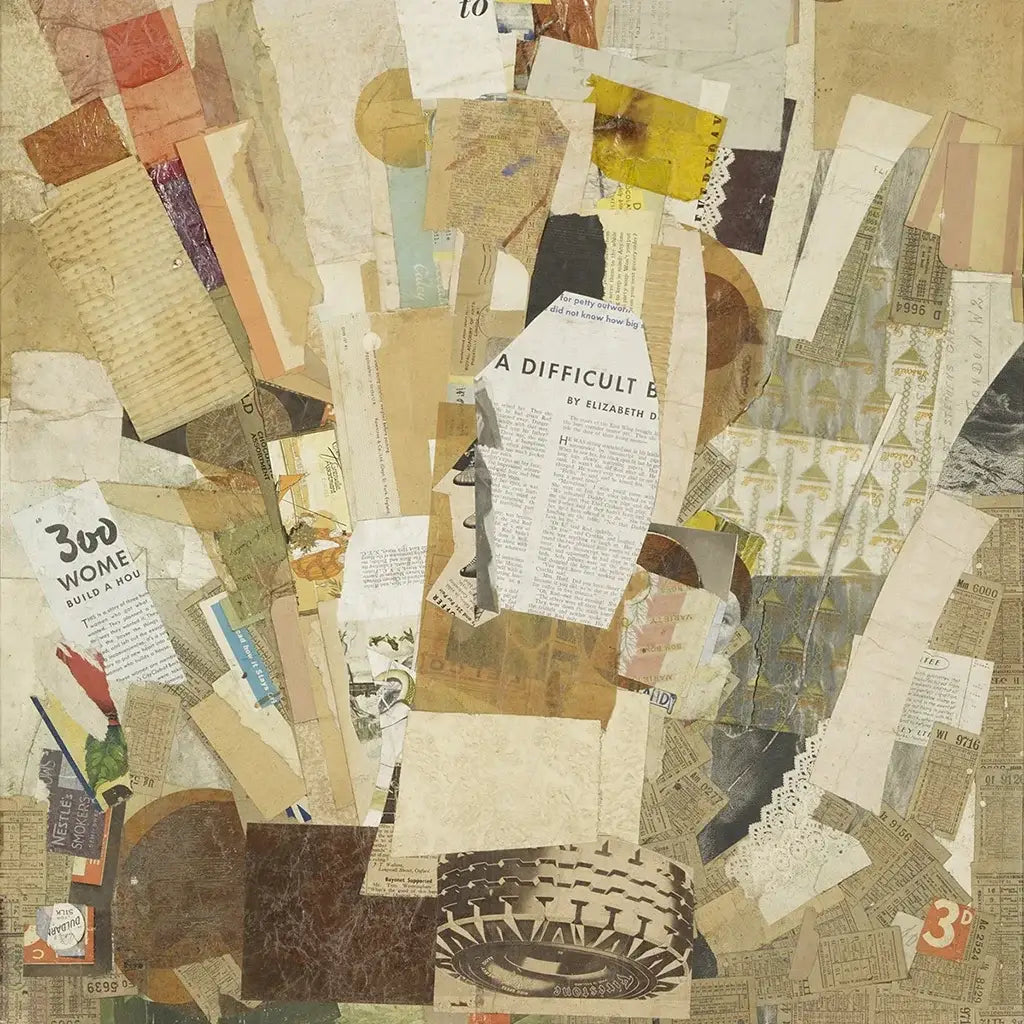

Kurt Schwitters, Difficult, 1942-43. Collage. 31.25 x 24 inches (79.37 x 60.96 cm).

...

Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948) was a German artist involved in both Dadaism and Constructivism, best known for his Merz and Merzbau works. He coined the term "Merz" to describe his unique style of art that involved using everyday objects to create his works. Schwitters created Merzbild (Merz-paintings), which were collages and assemblages made from various waste materials, such as prints, labels, wallpapers, and pieces of wood. And he never shied away from pointed, searing subject matter, including his time in Hutchinson internment camp.

Schwitters' Merz concept was a subsect of the Dada movement, tailored to his own artistic philosophies and visions. The name Merz was generated by chance through a collage that incorporated the German word "Kommerz" (commerce). This nonsensical and spontaneously generated word was similar in origin and philosophy to the title of Dada.

While Merz and Dada art are closely related, there are some differences between the two. Merz is a subsect of the Dada movement that was tailored to Schwitters' own artistic philosophies and visions. On the other hand, Dada was a broader art movement that encompassed various forms of art, including performance art, poetry, photography, sculpture, painting, and collage. Dada's aesthetic was marked by its mockery of materialistic and nationalistic attitudes.

Throughout his life, Schwitters created over 8,000 works, with around 2,500 remaining today. His innovative approach to art, fusing collage and abstraction, influenced artists such as Robert Rauschenberg. Schwitters was an outsider and individualist, choosing not to move to major artistic centers like Berlin or Paris after completing his studies at the Dresden Academy.

7

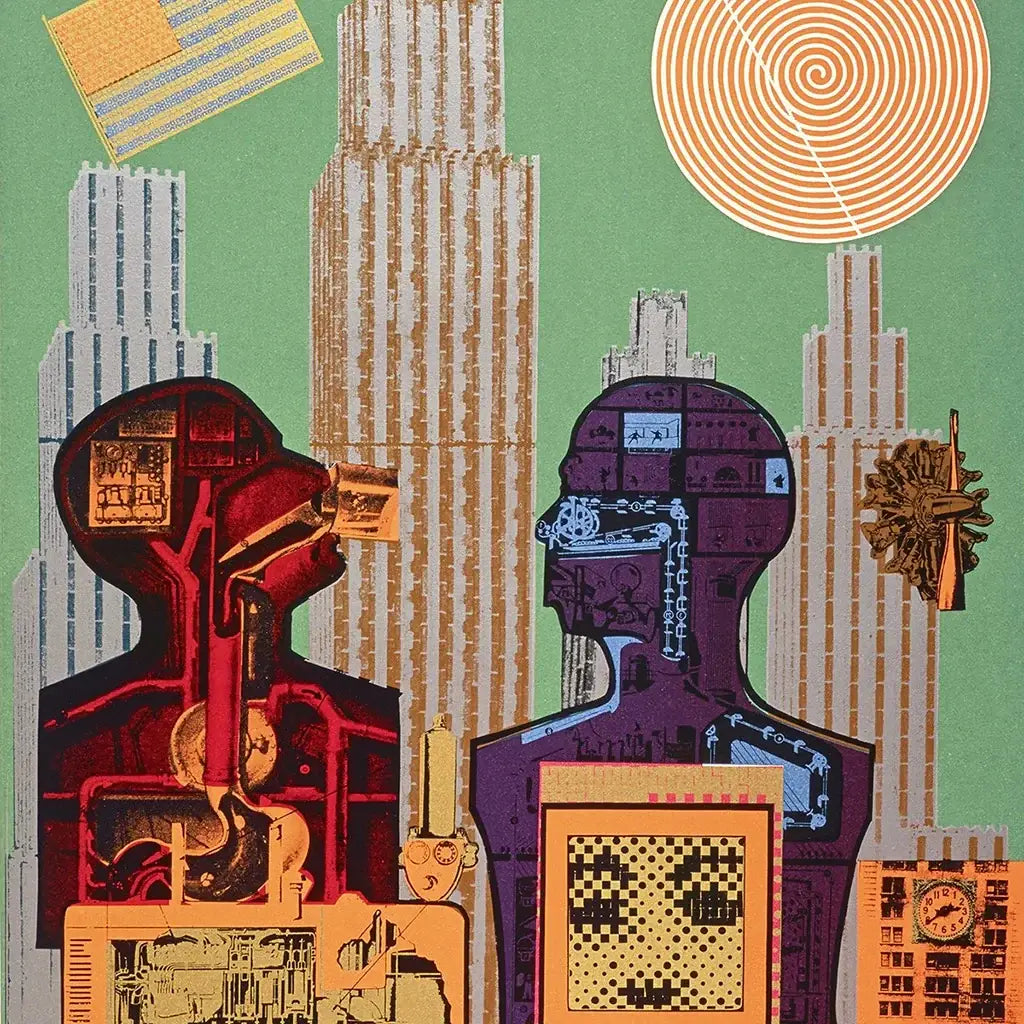

Eduardo Paolozzi

...

Eduardo Paolozzi (1924-2005) was a Scottish artist known for his innovative collage works that incorporated a mix of images from popular culture and technology. Born in Leith near Edinburgh to Italian parents, Paolozzi studied in Edinburgh and London before spending two years in Paris. He is widely considered to be one of the pioneers of Pop Art.

Paolozzi's works often challenged traditional notions of art and beauty by combining elements of Surrealism with popular culture, modern machinery, and technology. His early love for American culture led him to create collages using images from advertisements, representing the shinier, happier lifestyles that were emerging in post-war America. But he also played with that form and style — transmuting its over the top sensibilities into his mosaics and sculptures, most notably at Tottenham Court Road tube station.

His works were surreal in nature, as he combined magazine advertisements, cartoons, and machine parts into his art, anticipating the concerns of Pop Art. Paolozzi was particularly interested in the mass media and in science and technology, which influenced his art throughout his career. In addition to his collage works, Paolozzi also produced large-scale figurative sculptures, prints, and mosaic murals — their vibrant appeal lending "a kind of focus to the chaos".

8

Martha Rosler

Martha Rosler, Cargo Cult, from the series Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain, 1966–72. Photomontage printed as photograph. 39 1/2 x 30 1/4 in.

...

Martha Rosler, born in 1943 in Brooklyn, New York, is an American conceptual artist known for her feminist collages and photomontages. She works in various mediums, including photography, photo text, video, installation, sculpture, and performance, as well as writing about art and culture. Rosler's work often incorporates images from popular culture and advertising to question the role of women in society and challenge traditional gender roles.

Martha Rosler's work significantly influenced the feminist art movement by questioning the portrayal of women in society. She also used new technologies, such as video, to differentiate herself from male artists and the more traditional mediums of the art world. In the mid-1960s, she began creating photomontages exploring women's material and psychic subjugation, manipulating popular advertisements to expose their underlying ideologies. Her work, such as the "Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain" series (1966–72), combined various conceptual art practices attuned to feminist politics.

One of her widely known works, "Semiotics of the Kitchen" (1975), is a video parody of cooking shows that humorously addresses the implications of traditional female roles. By appropriating elements of pop culture, such as television and magazine advertising, Rosler's work critiques societal norms and expectations surrounding women.

Rosler's art practice extended beyond subject matter, as she believed that art could genuinely occupy a social role and provoke empathy and disidentification in the viewer. Her video works from the 1970s and 1980s scrutinized mass media's operations to reveal how they cultivated a complacent public. Influenced by the wave of feminist performance emerging from alternative art spaces in California, Rosler's work contributed to the development of feminist conceptual art and left an indelible mark on the contemporary arts scene.

9

John Heartfield

John Heartfield, Cover art for Kurt Tucholsky, Deutschland, Deutschland über alles, 1929 © The Heartfield Community of Heirs / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020 Akademie der Künste, Berlin.

...

John Heartfield (born Helmut Herzfeld; 1891-1968) was a German visual artist who pioneered the use of art as a political weapon, particularly through his anti-Nazi and anti-fascist photomontages. Heartfield's works often used satirical images and slogans to criticize the political climate of his time, especially against the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Third Reich.

Heartfield's photomontages are credited with creating some of the most iconic political posters of the 20th century due to their powerful visual impact and ability to convey strong political messages. From 1930 to 1938, he designed 240 pieces of anti-Nazi art, which were published in the AIZ magazine. These works were smuggled into Germany from Czechoslovakia, Austria, Switzerland, and Eastern France after the National Socialists took control.

Heartfield's artistic courage was equal to his physical courage, as he continued to create vehemently anti-fascist collages while living in Berlin until 1933. His photomontages foreshadowed the horrors of the Nazi regime and served as a powerful form of political protest, making him a significant figure in the history of political art.

John Heartfield's work has influenced numerous artists, graphic designers, typographers, advertisers, filmmakers, writers, and others who have found inspiration in his legacy. Artists from across the Eastern bloc, Soviet Russia, and the United States found inspiration in Heartfield's photomontages in the late 1960s and 1970s. For artists like Klaus Staeck, László Lakner, and Martha Rosler, among others, his work helped them confront worn-out leftist ideologies with a new visual language.

Heartfield's innovative use of transformed photomontage into a powerful form of mass communication. His unique method of appropriating and reusing photographs for political effect has inspired contemporary artists to use similar techniques to combat bigotry, ignorance, violence, and senseless war for profit. The John Heartfield Exhibition features work from collage artists such as Winston Smith, Thomas Young, and David King, who continue and expand on Heartfield's groundbreaking work.

10

Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso, The Bottle of Vieux Marc, 1913. Cut-and-pasted printed wallpapers, newspaper, charcoal, gouache, and pins on laid paper, 24 13/16 × 19 5/16 in. (63 × 49 cm).

...

Pablo Picasso, along with Georges Braque, played a crucial role in the evolution of collage art. They developed the technique of papier collé (pasted paper) in 1912, which marked a groundbreaking shift in the art world. Picasso's innovative approach to collage art inspired other artists and became a catalyst for artistic movements such as Cubism, Dada, and Surrealism.

One of Picasso's early collage work, "Guitar and Wine Glass," demonstrates his ability to create shading and structure by pasting and layering paper. His 1912 artwork "Still Life with Chair Caning" is another significant example of his collage work. In this piece, Picasso incorporated a piece of oilcloth with a chair caning pattern and a rope to frame the composition. This artwork challenged traditional ideas of art by combining everyday materials with painted elements, blurring the boundaries between high and low culture.

Picasso's collage works had a profound impact on the art world, inspiring artists across various movements, mediums, and styles to explore the practice of collage art. His inventive and innovative approach to art attracted artists due to its unique aesthetic and pieced-together process. As a result, Picasso's influence on the evolution of collage art is evident in the works of many artists who followed, such as David Hockney, Jasper Johns, and Martin Kippenberger.

11

Georges Braque

Georges Braque, Fruit Dish and Glass, 1912. Charcoal, wallpaper, gouache, paper, paperboard.

...

Georges Braque, along with Pablo Picasso, played a significant role in the evolution of collage art. They invented the technique of papier collé (pasted paper) in 1912, which marked a revolutionary shift in the art world. Braque took collage one step further by gluing cut-up advertisements into his canvases. He also stenciled letters onto paintings, blended pigments with sand, and copied wood grain and marble to achieve great levels of dimension in his paintings. Of course, collage existed well before then in other forms...

Braque's collage artwork, such as his 1912 artwork "Fruit Dish and Glass", combined pieces of faux-wood wallpaper with his Cubist depictions of objects. This technique called into question the formal ideas of perspective and space within art, as it created intersecting areas of collage elements and drawing within his work. His innovative approach to collage art influenced many contemporary artists and contributed to the growth and expansion of the collage art form.

During the collage phase of Cubism from 1912–14, inanimate objects dominated the imagery of Picasso, Braque, and Juan Gris. Braque's still lifes possessed an undercurrent of human drama, thanks to the ingenious combination of things and text. The use of real materials and textures in their collage compositions introduced a new dimension to Western painting, whose repercussions are still felt today.

Braque's work with collage had a lasting impact on the art world, inspiring artists across various movements, mediums, and styles to explore the practice of collage art. The inventive and innovative approach to art attracted artists due to its one-of-a-kind aesthetic and unique, pieced-together process. As a result, Braque's influence on the evolution of collage art is evident in the works of many artists who followed, such as Jessica Stockholder, Mark Bradford, Hannah Hoch, Kurt Schwitters, and John Stezaker.

...

Collage art is a unique and versatile medium that allows for endless creative possibilities. The famous collage artworks mentioned in this article have all made significant contributions to the art world through their innovative styles and techniques. Each artist has their own unique perspective, and their impact on the art world has resonated with other artists and influenced their work.

Whether it's using everyday objects, political satire, or questioning traditional gender roles, collage art has the ability to communicate complex messages in a visually stunning way. These artists have shown that collage art is more than just cutting and pasting, it's a powerful medium for self-expression and social commentary.

—

For Lazy Nerds & Visual Learners

Famous Collage Artists on YouTube

ICYMI

Which artist made the concept of collage into a form of art in 1912?

In 1912, the pioneering artist who transformed the concept of collage into a distinct form of art was none other than Pablo Picasso. During this year, Picasso unveiled "Still Life with Chair Caning," a remarkable work that marked the advent of collage as a significant artistic expression and marked the initiation of a new phase in the Cubist movement.

"Still Life with Chair Caning" featured an unconventional combination of materials and techniques. Picasso incorporated a strip of oilcloth printed with a chair caning pattern onto an oval-shaped canvas. The painting was further framed with a rope. This innovative fusion of various elements, along with the incorporation of non-traditional materials, like the oilcloth, challenged conventional artistic norms and introduced an avant-garde approach to art-making. This groundbreaking artwork paved the way for the exploration of new possibilities in visual representation and significantly expanded the boundaries of artistic expression.

In addition to its impact on visual arts, Picasso's innovative use of collage had broader implications for artistic philosophy and creative thought. The introduction of collage as a viable artform challenged established ideas about the nature of art materials, composition, and representation. This approach encouraged artists to explore unconventional materials, textures, and forms, fostering a spirit of experimentation and redefinition within the artistic community.

The work of Hannah Höch is considered to be a part of what artistic style?

Hannah Höch's artistic style is firmly associated with Dadaism, an avant-garde movement that aimed to challenge traditional notions of art and society through its embrace of absurdity, anti-conformity, and experimentation.

Höch is best known for her photomontage works, a technique where she skillfully combined and juxtaposed cut-out images from magazines and newspapers to create intricate and thought-provoking collages. Her photomontages often featured a satirical and critical commentary on social and political issues, reflecting the Dadaist rejection of established norms and values.

Höch's participation in Dadaism and her mastery of photomontage techniques played a significant role in expanding the artistic possibilities of the movement. Her work challenged the prevailing notions of authorship and originality by appropriating and recontextualizing existing imagery, which resonated with Dada's ethos of subversion and iconoclasm.

Future Forecast

Why was the dada artistic movement important to future artists?

The Dada artistic movement holds profound significance for future artists due to its radical departure from conventional artistic norms, its subversion of established institutions, and its role in paving the way for subsequent avant-garde and experimental art forms. Emerging during World War I as a reaction against the horrors of war and the societal norms that seemed to have led to it, Dadaism was a force that shattered traditional artistic boundaries. Countless artists were inspired by the wild antics and bold anti-authoritarian nature of Dada, motivating them to expand the horizons of the art world.

One of the most iconic figures of Dadaism was Marcel Duchamp, known for his groundbreaking work "Fountain," a porcelain urinal signed with the pseudonym "R. Mutt." Duchamp's creation epitomized Dada's anti-art ethos, challenging traditional notions of aesthetics and forcing viewers to question the very essence of art. This audacious act had a profound impact on future artists by pushing them to rethink the very definition and boundaries of artistic expression.

The Dada movement played a pivotal role in changing the perception of art and breaking established rules. It disrupted traditional artistic mediums by incorporating found objects, collage techniques, and performance art, setting a precedent for artists to experiment with unconventional materials and methods. Dadaism's rejection of logic and its embrace of absurdity and irrationality influenced later movements such as Surrealism, which also aimed to tap into the unconscious mind and challenge rationality in art.

The movement's influence extended beyond artistic practices to challenge societal norms and authority. By ridiculing and rejecting conventions, Dadaists confronted the status quo, inspiring future generations of artists to use their creative expressions as a means of social critique and change. Dada's anti-establishment stance and its exploration of randomness, chance, and spontaneity also contributed to the development of conceptual art and performance art, both of which prioritize ideas and process over traditional aesthetic outcomes.

...

Main image: Eduardo Paolozzi, Turing 6, 2001. Colour photo-screenprint. 64 × 53 cm.