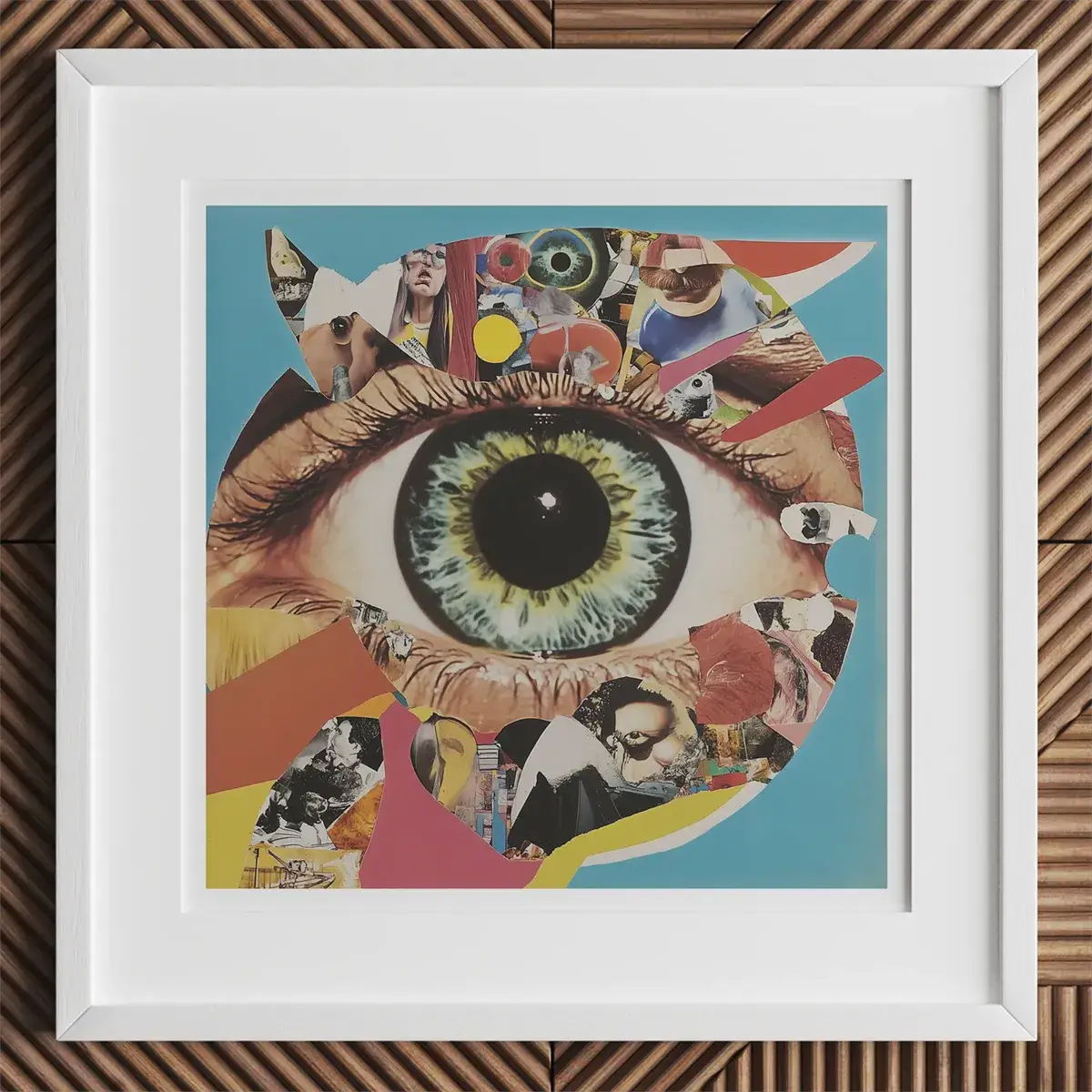

Cultural collage art has always been more than an assemblage of scraps – it is a mirror, held up to reflect the values, anxieties, and dreams of its time. From ancient artisans layering precious materials to digital natives remixing memes, each era’s collages reveal a chronicle of human experience.

Consider an elderly widow in 1772, Mary Delany, who pressed bits of colored paper into the likeness of a geranium and wrote, “I have invented a new way of imitating flowers”. In that humble act of craft she unwittingly echoed a practice stretching back centuries and continents – piecing the world together in visual form.

Collage, from the French coller (to glue), literally and metaphorically binds the ephemeral into meaning. It allows disparate images and materials to converse on the canvas, creating a layered syntax that is at once poetic and incisive. Over time, artists have used this syntax to document history, challenge authority, and weave personal and collective identities.

Today, as we scroll through digital collages on social media or encounter immersive collage-inspired installations in museums, we are participating in a lineage that spans ancient Chinese scrolls, Dadaist photomontages, punk zines, and beyond.

This article's journey will trace the transformation of collage from its ancient origins to the digital age, examining how cultural forces shaped its evolution at key junctures. We’ll see how each layer of collage – each fragment torn and pasted – carries the imprint of a time and place. A story of creativity born from complexity, an art form continually reborn to speak to new realities.

Key Takeaways

- Collage art provides a unique lens into the complexities of cultural and historical contexts.

- The medium has continually evolved, reflecting shifting societal values and ideologies.

- Significant art movements, including Dadaism and Surrealism, utilized collage for socio-political commentary.

- Collage serves as a chronicle of human history, ingrained with symbols and motifs from various cultures.

- Through collage, artists offer both a preservation of and a challenge to cultural identities.

- The technique's adaptability has allowed it to maintain relevance in the face of a rapidly changing world.

Long before “collage” was a defined art term, humans were assembling fragments to tell their stories. In prehistoric times, our ancestors combined natural materials – flower petals, shells, feathers, butterfly wings – to adorn objects or create ritual displays.

These early acts, though not art-for-art’s-sake, reveal a fundamental instinct to collect and compose meaning from the world around us. By attaching one element to another, prehistoric people were essentially making the first collages, using the stuff of daily life to convey ideas or spirituality.

One pivotal innovation supercharged this impulse: the invention of paper in China around 200 BCE. With paper, a flexible new surface was born, and soon artisans found they could cut and glue it in inventive ways. Historical records suggest that by the time of the Tang Dynasty, Buddhist monks were pasting paper sutras (scriptures) and images together as devotional art.

Collage, in this context, was a tool of piety and preservation – bits of printed prayers assembled into a greater whole. This set a precedent for collage as a meaning-making practice, embedding cultural values (in this case, religious devotion) into the artwork’s very materials.

Japan took up the practice not much later. By the 10th century, in the Heian period, Japanese poets and calligraphers were known to glue poems onto decorated paper backgrounds as part of the art of tsugimono, creating visually layered poetry scrolls. They might attach delicate cut papers with gold or silver leaf and inked characters to assemble a harmonized design – essentially an early paper collage marrying text and image.

By the 12th century, Japanese artists were also pasting paper onto silk to embellish screens and scrolls, an early forerunner of collage in fine art. These refined uses in East Asia were paralleled by folk practices elsewhere: in central Europe by the 13th century, people used collage-like techniques as a craft to decorate their homes – for example, combining fabric, photos, and keepsakes into what we might call proto-scrapbooks or memory boards.

Collage’s pre-history is thus a global tapestry. In many indigenous and folk traditions, we find analogous techniques of assembling pieces:

- Mola textiles made by Guna women in Panama layer colored fabrics in a reverse appliqué (a textile collage) to depict local stories

- Quilting traditions in Africa and the African diaspora stitch together disparate cloth scraps into unified narratives

- Tibetan Buddhist sand mandalas assemble millions of grains of colored sand into cosmic diagrams, only to sweep them away – a poignant ritual of creation and dispersal akin to collage’s ethos of impermanence and recombination.

Each of these practices uses a collage principle: bringing fragments together to create meaning transcending any single piece.

By the Renaissance and Baroque eras in Europe, collage elements appeared in religious art and courtly crafts. Nuns in medieval convents crafted exquisite reliquaries and devotional images studded with cut parchment, fabric, and jewels – a spiritual collage of materials.

In baroque cabinet of curiosities, collectors would mount butterflies, coins, and prints in elaborate arrangements, effectively collaging nature and art as a way to catalog the world’s wonders.

These early collages served as cultural mirrors of their time: the Chinese paper collages reflected a society cherishing scholarship and faith, the Japanese scroll collages mirrored a courtly culture that valued poetry and elegance, and the European folk collages spoke to domestic life and personal memory.

By the 18th century, collage as we know it began to emerge more clearly. Mary Delany’s work is a prime example: between 1772 and 1783, at the court of England, this genteel grandmother hand-crafted 985 botanical collages so scientifically accurate that botanists marveled one could “describe botanically any plant...without fear of error” by looking at them.

Delany called her flowers “paper mosaicks,” an apt term highlighting how each was a composite of many paper snippets. Her artistic revival late in life – spurred by curiosity and grief alike – underscores a key theme: collage often flourishes in times of personal or societal upheaval, giving form to what is otherwise inexpressible.

Around the same era, Victorian collage became a popular pastime. Aristocrats and middle-class families alike kept scrapbooks and collage albums. Even the novelist Charles Dickens indulged, collaborating with a friend to cover a folding screen with hundreds of cut-out engravings.

Victorian domestic collages, created for amusement, were nonetheless cultural artifacts: they gathered the visual culture of the day (newspaper clippings, printed images) into new narratives, much as we might make a digital collage of news photos to comment on current events.

Through these early examples, collage art established two enduring roles: as a means of preserving the past (pressing treasured pieces into a new whole) and as a means of subversion or play, recombining the world with whimsy or critique. These roles would become even more pronounced as collage entered the realm of modern art.

The rich history of collage art is steeped in a medley of cultural dynamics, serving as a visual lexicon teeming with commentaries and revolutionary ideas. This section undertakes a journey of chronicling the timeline of influences in art, pinpointing the metamorphosis of collage from its inception to the powerhouse of expression it is today.

By exploring cultural influences, we not only acquire insight into this transformative medium but also appreciate the pivotal roles played by a constellation of artists and movements in shaping its trajectory.

- The nascent stages of collage can be traced back to the invention of paper in China, which eventually led to the first recorded instances of paper collages used by monks for religious texts, symbolizing the earliest historical context of collage art.

- Fast-forward to the early 20th century, when Cubism sparked a pivotal shift as artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque began incorporating mixed media into their work, marking a significant development in the timeline of influences in art.

- The anti-war sentiments and societal critique of the Dada movement empowered artists, including Hannah Höch and Kurt Schwitters, to use collage as a form of rebellion—critiquing cultural constructs and setting new precedents in history of collage art.

- Surrealists, later on, infused collage with elements of dream and fantasy, with artists like Max Ernst utilising it as a canvas for subconscious explorations and reflecting cultural influences through juxtapositions that blurred reality and dream.

- Mid-20th century brought forth Pop Art, where collage turned a mirror on consumer culture, with artists like Richard Hamilton and Andy Warhol dissecting and reassembling popular imagery to comment on the commodification of culture.

- The late 20th into the 21st century saw collage art continue to evolve, with digital technologies and global connectivity ushering in a new era. This period has witnessed artists leveraging collage for social commentary and digital activism, ultimately broadening its historical and cultural significance.

By examining this storied past, it is evident that collage has continually served as a medium of choice for artists keen on exploring cultural influences. Its adaptability and propensity for eclectic amalgamations have rendered it an ever-evolving canvas, reflecting the ever-changing face of human culture.

The historical context of collage art is not simply a past to be studied but an ongoing conversation, punctuated with layers of meaning that speak to the fluidity of time and culture.

- Cubism's experimentation reflects the modernizing world’s outlook and the overlapping of different perspectives through collage.

- Dada's utilization of collage underpins cultural critique and the deconstruction of pre-war values.

- Surrealism's dream-like collages dissect the crevices between tangible reality and the unfettered mind.

- Pop Art’s vibrant tableaus depict the burgeoning influence of mass media and consumer culture on individual and societal identities.

- The digital age’s remix culture and internet memes present a new frontier where collage art's historical narrative continues to unfold.

Within this rich tapestry lies an intricate network of eras, ideologies, and methodologies, all contributing to the robust, multifaceted essence of collage art. It is a history not merely of artists and their works but of how those elements reflect and challenge the eras they emerged from, providing cultural context and influencing successive creative generations.

In the early 20th century, collage exploded onto the avant-garde art scene, forever changing the course of modern art. The catalyst was Cubism, the radical art movement led by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in Paris.

By 1912, Picasso had grown restless with merely painting a still life. In a bold move, he pasted a piece of commercially printed oilcloth with a cane chair pattern directly onto his canvas Still Life with Chair Caning (1912). It was a scandalous gesture – “the shocking incongruity of introducing a folk art device into ‘serious’ art”.

By inserting a real-world material into the painted illusion, Picasso collapsed the boundary between art and life. As one Metropolitan Museum commentary notes, this was a “radical act – inserting a fragment of reality into the fictive realm of painting,” a witty imitation of reality that both mocked and honored tradition.

Braque, not to be outdone, soon glued pieces of wallpaper and newspaper print into his artworks. Thus was born Synthetic Cubism, and with it the formal introduction of collage technique in fine art.

Why did this happen in 1912? Culturally, the world was changing at breakneck speed – modernity was in full swing with its telephones, automobiles, and daily newspapers. Cubist collage reflected a modern worldview: one of fragments, simultaneity, and multiple perspectives.

By cutting up and reassembling bits of the everyday (journal clippings, tobacco wrappers, wallpaper), Picasso and Braque aimed to capture the overlapping realities of modern life. Collage was the perfect medium for this. It allowed artists to juxtapose different textures and viewpoints on one plane, much as a city presents a collage of sights and sounds. As a result, Cubism’s experimentation with collage became a foundation for much of 20th-century art. The very word “collage” entered the art vocabulary through these experiments.

Other artists quickly picked up the scissors (and glue). In Italy, the Futurists pasted words and images in their manifestos and zany typographic designs, trying to convey the chaos of the machine age. In Russia, Constructivists assembled abstract collages from paper and print to advance revolutionary ideals. But it was in the midst of World War I that collage took on an even more combative cultural role: the birth of Dada.

Dada: Glue as a Weapon of Dissent

In 1916, as war raged in Europe, a band of expatriate artists and poets in Zurich – Hugo Ball, Hannah Höch, Tristan Tzara, Kurt Schwitters, Raoul Hausmann among them – rebelled against everything society stood for. They called their anti-movement Dada, a nonsense word befitting their outrage at the senseless violence of WWI. Collage and its photographic cousin photomontage became Dada’s most explosive weapons.

Why collage? Dadaists found in the cut-and-paste technique a metaphor for the fractured world around them. By physically cutting apart newspapers, advertisements, and photographs – the very fabric of bourgeois society’s visual culture – and reassembling them in absurd or jarring ways, they aimed to literally cut through the illusions of nationalism, propaganda, and traditional art.

Hannah Höch, a Berlin Dadaist, pioneered photomontage to critique gender roles and politics. In her 1919 collage Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany, she sliced up images of German political figures and mass media imagery, reassembling them into a chaotic, biting satire of Weimar society. The title itself suggests domestic tools (a kitchen knife) used to carve up bloated authority (the “beer-belly” of the establishment). Höch’s work, like many Dada collages, was a polyphonic critique – multiple voices and meanings emerging from the juxtaposed fragments, a visual protest against a singular, rational narrative.

Dada collage introduced several key cultural tactics that echo through art to this day:

Photomontage as Social Critique: Artists like Höch and John Heartfield combined and retouched photographs to create searing political messages (Heartfield famously mocked Hitler by collaging the Führer’s portrait to reveal a stash of gold coins in his stomach – implying greed fueling fascism). This technique is a direct ancestor of today’s political memes and Photoshop satire.

Chance and Irrationality: Dada collagists often embraced chance arrangements of fragments (Jean Arp, for example, dropped torn paper pieces and glued them where they fell) to reject the idea of premeditated order. This free association of images mimicked the era’s sense of dislocation, and also presaged Surrealist methods.

Typography and Graphics in Art: Dada blurred art and publishing. Clipped words, typefaces, and commercial logos found their way into collages, eroding the barrier between fine art and mass media. In doing so, Dada collages acknowledged that culture itself was a collage of high and low, earnest and absurd – a notion that would only grow stronger in postmodern art.

In the 1920s, many Dada artists evolved (or devolved) into Surrealists, carrying collage techniques with them into new conceptual realms. The Surrealist movement, enamored with Freud’s theories of dreams and the subconscious, saw collage as a means to access bizarre and uncanny imagery that might arise seemingly by accident.

Max Ernst created collages from 19th-century engravings to form fantastical scenes (his 1934 book Une Semaine de Bonté is a novel in collage, remixing Victorian illustrations into absurd, dreamlike vignettes). The Surrealists valued how collage could make familiar images strange by wrenching them out of context.

As one art historian observed, the act of splicing together disparate images mirrored Surrealist beliefs that meaning is generated by the subconscious in illogical leaps. A man’s head on a fish’s body, or a doll pasted in a forest – such irrational combinations were windows into the unconscious mind.

Yet, even in its dreamiest applications, collage in the hands of the Surrealists remained a cultural barometer. It captured the disillusionment of a world after war, where old certainties (political, social, religious) were cut apart, and new, unsettling realities were assembled from their pieces.

Collage also provided a way to process the onslaught of modern media imagery. As newspapers, magazines, and advertisements proliferated in the 1920s, artists literally had more raw material than ever to cut up. Surrealists took advantage of this flood of images to probe the collective psyche: each collage was like a Freudian dream interpretation of modern culture, piecing together the residues of mass media into revelations or nightmares.

By the late 1920s and 1930s, collage had established itself as a core technique of the avant-garde, used not only in Europe but globally. Latin American modernists like José Orozco experimented with collage in murals and prints; in Japan, avant-garde magazine Mavo featured collage works; and in the United States, the young Joseph Cornell began creating his beguiling collage-like assemblage boxes, filled with Victorian bric-à-brac arranged in surreal ways.

Indexed Timeline: Key Moments in Collage History (1900–1940) – a quick reference of pivotal collage breakthroughs and their cultural context:

- 1907–1911: Picasso and Braque develop Analytic Cubism (fragmenting form). By 1912 they transition to Synthetic Cubism and make the first fine art collages (e.g., Picasso’s Still Life with Chair Caning), introducing wallpaper, newspaper, and rope into painting. Significance: Collage enters high art, reflecting a modern reality where art and everyday life fuse.

- 1916–1920:Dada emerges (Zurich, Berlin, Paris, New York). Hannah Höch’s photomontages and Kurt Schwitters’ Merz collages use bus tickets, newspapers, fabric, and images to attack bourgeois culture and war propaganda. Significance: Collage becomes a tool of protest, parody, and cultural critique.

- 1924:Surrealist Manifesto published in Paris. Max Ernst’s collage novels (1921–34) and others use collage to conjure dreamlike scenes. Significance: Collage used to explore the subconscious and irrational, commenting on the fractured post-WWI psyche.

- 1931:Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme exhibits collages and objects (Paris). Joseph Cornell begins creating assemblage boxes in New York in the 1930s, a three-dimensional extension of collage principles. Significance: Validates collage as fine art internationally; collage aesthetics spread to America, influencing emerging artists.

If the early 20th century saw collage used to dismantle old world orders, the mid-20th century saw it employed to navigate the new world of mass media and consumer culture. The period after World War II was marked by an explosion of advertising, television, printed images, and commodities – a glut of visual stimuli that itself felt like a giant collage assaulting the senses. It is no surprise that artists of the 1950s and 1960s turned (again) to collage to make sense of, or critique, this new reality.

Proto-Pop: Hamilton’s 1956 Time Capsule

In 1956, a seminal collage by British artist Richard Hamilton asked (and cheekily answered) the question: “Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?” The collage depicts a modern living room overflowing with consumer goods and pop culture icons: a bodybuilder proudly holds a giant lollipop labeled “POP”, a tin of ham sits on a coffee table, a comic book cover and a tape recorder adorn the walls.

Hamilton clipped these images from American magazines and assembled them into a satirical snapshot of the emerging consumer society. This one artwork is often cited as the first work of Pop Art, with collage at its core. The message was clear – modern life is collage, a bombardment of disparate images and products all vying for our attention and desire.

Hamilton’s collage heralded a shift. In the Pop Art movement of the late 1950s and 1960s, artists gleefully embraced collage and assemblage to celebrate, criticize, or simply reflect the new media-saturated culture.

Andy Warhol, though known for silkscreen painting, also used collage techniques in his early works (like his 1960s photo-collage experiments arranging repeated images of celebrities and products).

Robert Rauschenberg built monumental combines – half painting, half assemblage – plastering newspapers and photographs onto canvases and even incorporating real objects like a stuffed goat or a tire.

These were collages in three dimensions, chaotic accumulations that captured the raw texture of American life. Rauschenberg famously said he worked “in the gap between art and life,” and his collage-based combines are exactly that: neither fully illusory art nor raw reality, but a hybrid.

Across the ocean, European Pop and Nouveau Réalisme artists were doing much the same. In 1960, French artist Mimmo Rotella tore down street posters and re-collaged their fragments into new compositions (he called this décollage, literally un-gluing, as he subtracted and rearranged rather than adding). The Nouveau Réalistes in France (like Jacques Villeglé) similarly lifted graffiti-covered posters and exhibited them as collages of “real life” urban visual culture.

What unites these Pop-era approaches is a sense that art should reflect the bombardment of images people were experiencing daily – the magazine ads, film stars, comic strips, and commercial packaging that had come to define postwar society’s dreams and aspirations.

Collage in this era often had a playful, ironic edge. Unlike the angry Dadaists or earnest Surrealists, Pop artists approached cultural imagery with a mix of fascination and irony. Yet there was critique embedded in many of these works. Hamilton’s collage is almost clinical in how it dissects a consumerist interior; Warhol’s repetitions of Marilyn Monroe or a Campbell’s soup can, while celebratory on the surface, also ask us to consider how mass reproduction and media shape our desires.

Collage was the ideal format for Pop art’s questions because it is fundamentally an art of appropriation – it takes existing images (often commercial ones) and re-contextualizes them. By doing so, collage art can expose the mechanics of media images: how they persuade, glorify, or deceive.

As art critic Donald Kuspit observed, a great strength of collage is its potential to undermine given ideas about the world, to deny the absoluteness of consensus reality. In the 1960s, the “consensus reality” was that consumption = happiness; Pop collages playfully poked holes in that by recombining the very signs of consumption into ambiguous art.

Collage for Protest and Identity (1960s–1970s)

The 1960s and 70s were turbulent times – civil rights movements, feminist movements, anti–Vietnam War protests – and collage once again became a favored tactic for activists and artists speaking truth to power.

Collage is inherently democratic: one doesn’t need a formal art education to cut and paste, and one can use cheap, accessible materials like magazines, flyers, and photographs. Thus, it naturally served the counterculture.

Consider the era’s political posters and underground zines. The antiwar movement often employed collaged photographs to shocking effect (e.g., images of Vietnamese children overlaid on an American flag). In 1967, Carolee Schneemann, an avant-garde performance artist, created “Body Collage”, a piece in which she rolled naked in glue and paper shreds. It was a visceral feminist statement – woman becoming collage – challenging the objectification of the female body by reclaiming it in a chaos of pasted material.

Feminist artists like Hannah Wilke and Martha Rosler in the 1970s used photomontage to critique gender roles, much as Höch had done but now addressing 1960s domesticity and the beauty industry. Rosler’s series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (c. 1967–72) pasted gruesome Vietnam War images into glossy magazine interiors, collapsing the distance between comfortable American homes and the war overseas – a powerful political collage that circulated in underground newspapers rather than art galleries.

Meanwhile, in music and graphic design, collage aesthetics signaled rebellion. The punk rock movement adopted a cut-and-paste DIY look for gig posters and album covers – arguably the influence of Dada revived.

The famously anarchic flyer for the Sex Pistols’ single “God Save the Queen” (1977) by Jamie Reid features the Queen’s portrait defaced with ransom-note style lettering, a direct descendant of Dada photomontage. To produce that ransom-note text, Reid literally cut letters from newspaper headlines. This “ransom note” collage style became synonymous with punk’s anti-authoritarian stance. In essence, each collage was a little revolution, rearranging the symbols of power into visual rebellion.

Collage also became a means for marginalized voices to assert their identity. African American artists of the 1960s and 70s like Romare Bearden embraced collage to depict Black life in America. Bearden cut up magazine photographs, patterned paper, and his own drawings, assembling them into vibrant, improvisational scenes of African American history and everyday experience – jazz musicians, baptisms, street life in Harlem.

Romare Bearden's “patchwork” aesthetic resonated with quilt-making traditions and Blues improvisation, linking collage to a cultural heritage of Black creativity born from assembling what’s at hand. It also allowed Bearden to literally insert Black faces and bodies into the art historical narrative, subverting a canon that had long excluded them. In doing so, he influenced later generations to use collage for personal and political storytelling.

By the late 1970s, collage had permeated nearly every art form and corner of society – from high art (museum shows of Schwitters or Cornell) to pop culture (music fanzines, comic books) to political activism (protest art).

The idea that anything could be art once combined thoughtfully was now largely accepted. Collage, once controversial, was now a common visual language. Yet its journey was far from over; in fact, the digital revolution was about to propel collage into an entirely new dimension.

As the 20th century gave way to the 21st, collage underwent yet another transformation – this time, propelled by digital technology. The advent of personal computers, image editing software like Adobe Photoshop (est. 1990), and, later, the vast image-sharing capabilities of the Internet, meant that cutting and pasting could be done in virtual space with unprecedented ease. We entered what could be called the age of digital collage, and its impact on visual culture has been profound.

In the digital realm, the world itself becomes an unlimited palette for collage. With a few clicks, an artist (or anyone with a computer) can grab an image of the Mona Lisa, combine it with a NASA photograph of Mars, add in text or graphics, and create a composite that can be shared globally within seconds.

This new freedom has meant an explosion of collage-based content in everyday life – from the political meme that pastes a politician’s face onto a cartoon body to make a point, to the aesthetic of remix in music videos and advertising (where quick-cut montages are essentially moving collages).

Importantly, the ethos of collage – its spirit of juxtaposition and recombination – has become a dominant mode of communication in the digital era. Social media feeds are effectively collages of content from myriad sources.

The Internet meme, arguably the folk art of our time, often relies on collage principles: consider the popular “distracted boyfriend” meme, which took a stock photo of a man and woman and allowed users worldwide to overlay their own text labels or images, turning one photograph into thousands of collaged commentaries on everything from relationships to socio-political issues.

Digital collage has democratized what was once the domain of avant-garde artists. Now teenagers with free apps can create layered, ironic visual jokes that echo Dada’s irreverence or Pop’s cultural commentary. As scholar Katherine Lee observes, “in the digital era, a spirit of rebellion similar to Dada’s movement against established structures is demonstrated through...existing expressions using digital application”. The cut-and-paste revolution that began in Zurich in 1916 finds new life on Instagram and Reddit in our time.

Digital tools have also expanded the formal possibilities of collage. Photomontage can be seamless now – images can be blended and manipulated such that the collage is nearly imperceptible as one. This has led to the rise of things like the “Photoshop battle”, where internet users compete to create the wildest composite image, and also to more nefarious trends like deepfakes (AI-manipulated videos).

The double-edged nature of collage as a communication act is evident here: on one hand, it’s a creative dialogue across time and space (a digital collage can incorporate imagery from disparate cultures and eras, truly a “trans-aesthetic code” in dialogue). On the other hand, the ease of collage in digital media means images can be deceptively altered and widely believed.

As Agustina Dewi et al. point out in a 2024 study on digital collage, “with the spirit of Dadaism that contains a free mind and open creation... collages as a communication process are also possible to frame messages and create fallacy”. In other words, the very freedom and power of collage – to recombine reality – can be used to distort truth (think of propaganda montages or misleading memes) just as easily as to reveal it. This makes visual literacy – understanding how images can be doctored or remixed – a crucial skill today.

In the art world, digital collage has become a respected genre of its own. Artists like David Hockney began experimenting with early digital collages on the iPad, while countless younger artists exclusively use digital means to create collage art that exists as prints, projections, or NFTs (non-fungible tokens). What’s notable is that despite the high-tech tools, the sensibility of these works often circles back to collage’s roots: they are mirrors of contemporary culture.

Digital artist Peggy Ahwesh created video collages from YouTube footage to comment on consumerism and waste, echoing Pop Art themes but through a 21st-century lens. Kenneth Tin-Kin Hung, a digital collagist, makes baroque political cartoons by stitching together internet images of politicians, corporate logos, and art historical paintings – very much in line with the tradition of Heartfield or Hamilton, but animated and online.

In design and advertising, the collage aesthetic is ubiquitous – magazine layouts layer text and image in playful ways, and TV commercials rapidly intercut images to sell lifestyles as much as products, all of which owes a debt to the pioneers of collage.

It’s also worth noting that the digital era has sparked a renewed interest in analog collage. Perhaps as a reaction to the slickness of Photoshop, many artists and hobbyists have returned to scissors and glue, reveling in the tactile, accidental discoveries that physical collage allows.

Collage collectives and zine fests around the world celebrate cut-paper collage as an accessible, low-tech art form that anyone can do with recycled materials – an inherently sustainable practice in an age of concern about waste. The Collage Research Network, founded in 2018, and exhibitions like “Cut and Paste: 400 Years of Collage” (National Galleries of Scotland, 2019) have highlighted the rich history and continuing innovation in collage, bridging academic study and artistic practice.

One could argue that our whole cultural moment is collagic: we build identities by curating bits of media (our playlists, our Pinterest boards, our Instagram feeds), we debate by mashing up information and references, and we create new content by endlessly recombining old content. In a sense, collage has transcended art to become a way of life – a dominant mode of processing the flood of images and data around us.

Through all these changes, the essence of collage remains what artist Louise Nevelson observed in 1975: “the way I think is collage”. We make meaning by connecting fragments, by seeing relationships between the bits and pieces we collect. Collage art, whether made with temple ruins, printed paper, or pixels, externalizes that very human cognitive process.

Collage art, in all its forms – from the humblest scrapbook to the grandest digital projection – stands as a testament to human creativity and cultural resilience. It is an art form born of resourcefulness (making do with whatever materials are at hand) and vision (seeing the potential in fragments).

Over history, collage has served as a preserver of memory, a weapon of criticism, a vehicle for fantasy, and a medium of connection across disparate ideas. Collage’s great power lies in its capacity to hold multiple truths and contradictions in one frame: it is at once itself and something else, the original pieces and the new whole.

Looking back, we see a transformation from ancient to digital:

- What began as relics and devotional crafts in ancient times evolved into a modern avant-garde strategy to break art free from its gilded cage.

- The early 20th-century artists who tore up the rulebook (and the newspaper) with scissors paved the way for art to directly engage with reality’s messiness.

- Mid-century collage artists mirrored the boom of mass media, critiquing and immortalizing the pop age’s icons in equal measure.

- Global and marginalized voices adapted collage to tell their own stories in a visual language not bounded by academic tradition.

- And the digital age blew the doors open for collage to become a universal vernacular, even as it challenges us to discern fact from fiction in a world of endless remix.

As a cultural mirror, collage has a remarkable way of showing us things we normally overlook. A scrap of a propaganda poster in a Dada collage forces us to really see the absurdity of the message. A juxtaposition of a magazine model with an ancestral mask can speak volumes about colonialism and identity. A meme that collages a famous painting with modern celebrities can spark a laugh – and perhaps a reflection on how much or little has changed. Each era’s collages are thus primary sources for future historians: they freeze in place the concerns and inspirations of their makers.

In the 1960s, critic John Berger wrote, “All art is in some way collage.” Over the course of this journey, we’ve seen the truth of that statement. Collage is not only an art technique but a way of thinking and seeing – recognizing that meaning is often constructed, not inherent, and that by rearranging pieces, we can rearrange perception.

Collage invites an almost archaeological appreciation: beneath the surface image lies each fragment’s original context, and digging into those layers reveals rich historical and cultural strata. A single collage might contain paper aged by time, words from another language, images from disparate cultures, all layered in dialogue.

In our current moment, where cultures intermingle and information inundates, collage feels more relevant than ever. It reminds us that something beautiful and coherent can emerge from chaos, that diversity of elements can lead to harmony or at least provocative conversation. It also reminds us to question what we see – to notice the seams and ask why these pieces were put together this way. Collage as an art form encourages a critical eye and an open mind.

Finally, collage has proven to be an unending source of innovation. Artists today continue to push its boundaries, fusing it with new media (e.g., interactive collages with augmented reality) or old ones (reviving hand-cut techniques). The medium’s inherent adaptability – its “endless creative possibilities” as one artist put it – ensures it will never stagnate.

As long as there are new experiences, new materials, and new ideas in culture, there will be artists compelled to cut, tear, layer, and paste them into something novel. Collage, in reflecting culture, also creates culture: it can introduce new aesthetic orders, new meanings, and new ways of seeing.

In the layered legacy of collage, we find an art form that is truly a cultural palimpsest – written and rewritten by each generation, yet never fully erasing what came before. From a monk’s careful pasting of a sacred text in medieval China to a teenager’s digital remix trending online today, the collage speaks of an undying human urge to make sense of our world’s pieces, to craft unity from diversity.

It is art, history, and communication all at once. In viewing a collage, we are invited to peer not only at an image but at culture itself, reflected in a jagged mirror – one that, in its very fractures and juxtapositions, shows us a truer, richer picture of reality.