In an era teetering between woodblock reverie and steel-pressed revolution, Kamisaka Sekka (1866–1942) did not merely survive Japan’s lurch toward modernity—he choreographed it. While others bowed to Western winds or clung to fading glories, Sekka unlatched a door few dared reopen: the gilded chamber of the Rinpa school, a centuries-old visual language rooted in Kyoto’s poetic traditions and lush design sensibilities. But Sekka wasn’t a curator of corpses—he was a resurrectionist. He dragged Rinpa forward, dusting off gold leaf with the brisk sensibility of Meiji period design and infusing classical motifs with the pulse of a world on the verge of electricity.

Born into a fading samurai class, Sekka moved through a world shedding its own skin. Industrial trains screamed past crumbling temples; Europe’s Art Nouveau enraptured Japanese diplomats; and painting academies swapped scrolls for oils. Where many saw decay, Sekka saw compost—fertile ground for reblooming the visual legacy of his ancestors. He refused the narrative that modernity must mimic Europe. Instead, he redrew Japan’s destiny in pigment, pattern, and pageantry, proving that Japanese art history could be a site of innovation rather than inheritance.

By channeling Rinpa’s bold patterning, lyrical rhythm, and natural harmonies into everything from folding screens to department store catalogues, Sekka disarmed the binary between craft and fine art. He transformed ephemeral scroll paintings into reproducible nihonga prints, turning tradition into a dynamic framework for design modernism. Where others feared dilution, Sekka wove a tighter braid: gold-leaf and aniline dye, yamato-e lineage and Glasgow insight, lacquerware and lithography. His was not nostalgia, but mutation.

Like a bridge strung between chrysanthemum and circuit board, Sekka’s legacy is neither antique nor avant-garde—it is both, vibrating across time with clarity, daring, and quiet thunder. His contribution to visual culture remains a vivid answer to a question many still ask: how do we modernize without erasing the past?

Key Takeaways

-

Kamisaka Sekka’s artistry was a luminous bridge connecting Japan's storied past to its modern awakening, fusing the vibrant elegance of Rinpa tradition with daring avant-garde sensibilities, thus reimagining heritage into forms brilliantly fresh yet timelessly Japanese.

-

Through transformative journeys to the West, Sekka rediscovered Japan’s own aesthetic genius, turning global fascination with Japanese art inward, and reclaiming Rinpa’s poetic dialogue with nature and literature to sculpt an innovative visual language for the 20th century.

-

Sekka boldly dissolved the barriers between fine art and everyday design, democratizing luxurious Rinpa motifs through sumptuous woodblock prints, lacquerware, and textiles, embedding classical beauty within the rhythm of contemporary life.

-

A dynamic educator and visionary community leader, Sekka ignited a design renaissance in Kyoto, mobilizing artisans and creators to harmonize classical craftsmanship with international design currents, revitalizing the city as a radiant beacon of cultural creativity.

-

Sekka’s enduring legacy resonates powerfully in contemporary visual culture, from graphic design and fashion to museum exhibitions, his inventive spirit continuously inspiring artists worldwide, exemplifying how looking backward can become the most profound way to leap forward.

Early Life and Influences

Kamisaka Sekka, Hanami Season, (ca. 1910)

Kamisaka Sekka was born in Kyoto in 1866, just as the chrysanthemum-scented twilight of the Edo period gave way to the iron clang of the Meiji era. His family belonged to the waning samurai class, their swords sheathed forever by imperial decree. Yet while swords dulled, brushes sharpened. Sekka grew up surrounded by Kyoto’s lingering grandeur—its temples still echoing with seasonal poetry, its artisans clinging to generations-old craft. Into this friction of dissolution and devotion, Sekka planted himself like a pine on the banks of Uji: weathering change, yet shaped by it.

His first apprenticeship was under Suzuki Zuigen, a painter of the Maruyama–Shijō school, where nature was not just a subject, but a structure—rendered with a hybrid of realism and lyricism. There, Sekka learned to observe. To see how a ripple disturbed not only the surface of a pond but the silence surrounding it. This fusion of empirical observation and poetic impulse would become his signature.

But it was not Kyoto alone that taught him. At twenty, Sekka did the unthinkable—he left Japan. He wandered through the art salons of Europe, attending the Paris World Exposition like a pilgrim in reverse, studying not just technique but how Japan’s image shimmered in foreign eyes. The West was devouring ukiyo-e and Japanese design with feverish appetite. For Sekka, it was a revelation: the world did not need a Westernized Japan—it craved Japan itself.

Upon returning in 1888, Sekka apprenticed under Kishi Kōkei, a passionate collector of Rinpa school works. Under Kōkei’s guidance, Sekka rediscovered the visual haiku of Sōtatsu and Kōrin—gold-leafed minimalism, nature distilled to elegance. Their compositions didn’t describe—they evoked. And Sekka, newly fluent in European design and electrified by Japonisme’s distorted mirror, understood the power of revival.

By 1901, he was dispatched to represent Japan at the Glasgow International Exposition. There, amidst Art Nouveau’s whiplash curves and opulent flora, he saw echoes of Kōrin’s chrysanthemums and riverbanks. The influence loop had completed a circle. Sekka’s clarity crystallized: modern Japan could find its voice not through mimicry, but through reassertion. In Ogata Kōrin, he found not a relic but a roadmap.

Sekka would later write that Kōrin embodied “pure nihonga.” But purity, for Sekka, was not about stasis. It was about distillation. And from that point forward, his mission was clear: reimagine the classical not as past, but as prologue.

The Modernization of Tradition

Kamisaka Sekka, Woman from Momoyogusa, (ca. 1910)

At the trembling threshold of the 20th century, Kamisaka Sekka stood not as a reactionary, but as a reinterpreter—a visual alchemist turning ancestral motifs into modernist gold. Where many artists equated progress with oils and vanishing inkstones, Sekka wagered that the future of Japanese visual culture lay buried in its roots. Not a retreat into nostalgia, but a transformation—a molting of Rinpa school tradition into a bold, abstract, design-forward phoenix.

His aim wasn’t simply to replicate Rinpa; it was to inject it with adrenaline. Using classical elements as scaffolding—wind-blown grasses, blossoms in seasonal drift, streamlined waves—Sekka recast them with flattened perspective, simplified contours, and industrial aniline pigments. These weren’t delicate brush studies of nature; they were nature reimagined as graphic iconography. Think ukiyo-e retooled by a Bauhaus disciple with gold leaf in his back pocket.

Through woodblock-printed albums, Sekka engineered a democratic reinvention of the decorative arts. No longer confined to elite salons, Rinpa design spilled onto textiles, postcards, lacquerware. He married nihonga lineage with mass production, anticipating design modernism’s central creed: beauty for all. His prints weren’t copies of past masterpieces—they were mutations, streamlined, sharpened, and made to live among the people.

In folding screens and painted scrolls, Sekka deftly wove in Western-style shading and subtle depth—but never to mimic. He wasn’t importing Impressionism; he was using its tools to carve out new aesthetic terrain. His vision crystallized in hybrid works like the crow-headed Tengu screen, where bold linework and dramatic chiaroscuro collide with poetic abstraction. Even negative space became an instrument of expression—emptiness as eloquence, silence as shape.

Most of all, Sekka distilled form. He refused realism’s pull, preferring silhouette to shadow, symbol to surface. A maple leaf might become a single vermilion slash. A stream reduced to silver geometry. In doing so, he placed Rinpa’s decorative vocabulary squarely in the lexicon of 20th-century abstraction.

Sekka’s true genius was recognizing that modern life didn’t require abandoning classical beauty—it required translating it. Collaborating with rising department stores like Mitsukoshi, he embedded this ethos into commercial design: ceramics, fabrics, stationery—objects where elegance met utility. Through these channels, the aristocratic grandeur of Edo morphed into a rhythm for daily life.

In Sekka’s hands, tradition became velocity—and Rinpa ceased to be a style. It became a strategy.

Masterpieces and Techniques

Kamisaka Sekka, Path Through the Fields, (ca. 1910)

Sekka was no archivist. He was an architect of afterlives—constructing futures from the sinews of the past. Where others saw traditional forms as ruins, he saw scaffolds, half-built bridges that could still be crossed. The tools of his resurrection were neither brushes nor pigment alone, but structure, sequence, rhythm. His works—woodblock books, folding screens, lacquerware—did not revive the Rinpa school; they restructured its DNA. With razor clarity and ceremonial elegance, he made Rinpa breathe in the lungs of a new century.

Chigusa

Chigusa, or A Thousand Grasses, didn’t whisper homage. It unspooled like an incantation—three volumes published between 1901 and 1903, each a thicket of classical motifs refracted through the modern eye. A shell-matching set becomes a compositional anchor. An incense kit, once reserved for imperial rituals, is flattened into a jewel-toned plane. Page by page, Sekka channeled Edo aesthetics into the language of early 20th-century Japanese design, refusing to revere the past as relic; instead, he vivified it as function.

Published by Unsōdō, Kyoto’s venerable printer, Chigusa was crafted with obsessive precision—multi-block impressions layered like memory itself: gold-leaf over deep cerulean, matte ink atop gloss. And yet, it was not the richness of pigment that defined it, but its clarity of intention. These were not images; they were visual axioms. Each one diagrammed Sekka’s belief that traditional Japanese crafts—textiles, ceramics, paper—still held secrets modernism hadn’t yet translated.

The compositions vibrate with symmetry and subversion. Bridges zigzag toward abstraction. Pines curl into calligraphic form. Chigusa wasn’t a flower arrangement; it was a replanting, a botanical treatise on the grammar of repetition, variation, and visual cadence. Through these pages, Sekka didn’t just rescue Rinpa from decorative death—he prefigured the modular logic of the graphic era to come.

Momoyogusa

If Chigusa was a garden, Momoyogusa—Flowers of a Hundred Worlds—was the storm that fertilized it. Published in 1909–1910, this three-volume album didn’t simply distill Rinpa motifs; it detonated them. Sixty plates of visionary velocity: a puppy tumbles in tribute to Sōtatsu, rice paddies fracture into near-cubist planes, chrysanthemums flatten into fields of pure color. Here, Sekka’s aesthetic vocabulary expands into architecture, abstraction, and coded rhythm.

The title itself—Momoyogusa, an archaic word for chrysanthemum—signals Sekka’s intent to tangle with time. He wasn’t interested in preservation; he was engineering temporal continuity, a form of design time-travel. He opened the volume with a newly composed poem by Sugawa Nobuyuki, a prelude that binds the work to the Heian poetic lineage while launching it into modern design futurism.

And yet the miracle is not literary—it is technical. The registration of color, the precision of overprinting, the saturation of mineral pigments, the alchemy of matte and shimmer—all orchestrated with a mastery that made woodblock printmaking, long considered quaint, suddenly feel cinematic.

These weren’t illustrations. They were theorems in design logic. Sekka used Rinpa as the base key, then modulated each chord until it played a wholly new visual scale—one leg rooted in Kyoto lacquer boxes, the other stepping into the syntax of global modernism. Museums now show Momoyogusa under glass, but it was never meant to be a relic. It was meant to ripple outward—its waves still felt in contemporary textile prints, graphic layouts, and UI color theory.

Folding Screens

Sekka’s byōbu—folding screens—did not divide space. They magnetized it. They stood as portals, thresholds where the viewer was invited to pass through form into atmosphere. His reimagining of Ogata Kōrin’s Irises at Yatsuhashi was not an act of flattery, but of deliberate tension. The screen appears familiar—bridges and blossoms—but its proportions are skewed, its rhythm unsettled. Negative space stretches like breath. The zigzagging bridge fractures into almost-symbols. Amid fields of lapis and gold, Sekka inserts white irises—interruptions in the pattern, whispers of dissent.

Technique here becomes language. He paints without outline using mokkotsu, letting form dissolve into hue. He drops wet pigment into wet pigment—tarashikomi—creating pools that dry like lichen on silk. But while these techniques are ancient, Sekka’s handling is not reverent—it is radical. They become tools of compression, subtle violence, and atmospheric drift.

In his woodblock Eight-Planked Bridge, the same motif bleeds out—black ink stammering across the page like a visual stutter, brushstrokes disassembled, structure trembling. Sekka doesn’t illustrate a scene; he reconsiders its geometry, its breath, its grammar. He makes space feel like a question.

Polymath

Sekka’s genius refused containment. His mind, unbound by medium, roamed from print to pigment to ceramic glaze, finding in each a new voice for the Rinpa revival. Where others painted scrolls, he drafted tableware. Where others designed with ink, he did so with gold leaf, textile, and shell. He wasn’t bridging “high” and “applied” art. He was smashing the division altogether.

With his brother Kamisaka Yukichi, a master of lacquer, Sekka created objects that didn’t decorate life—they participated in it. A food container shaped like a half moon, its surface kissed with silver blossoms, isn’t just functional. It’s ritualized geometry, domestic poetry made tangible. Each curve of lacquer is a line of calligraphy you eat beside, not read.

He designed ceramics that married traditional Kyoto glazes with shapes informed by Art Nouveau currents—pottery as sculpture, as visual koan. His works appeared in early 20th-century craft exhibitions, not as curiosities but as emissaries of a new Japanese modernity—one that used its own DNA, not imported genes.

Whether designing a box, a plate, or a fabric, Sekka’s principles remained unwavering: let negative space breathe, let line speak like verse, let pattern think like architecture. He wasn’t just making things. He was encoding a new design intelligence—and embedding it in the texture of ordinary life.

Sekka’s Role in Kyoto’s Design Renaissance

Kamisaka Sekka, Village Cherry Blossoms, (ca. 1910)

Kyoto at the turn of the 20th century could have become a museum of itself—a living city embalmed in nostalgia while Tokyo thundered ahead with iron tracks, oil paint, and Western academies. But then came Sekka, not as a savior but as a cultural strategist, orchestrating not a return to the past, but a ritual reactivation of it. He wasn’t interested in preserving old forms behind glass; he wanted them woven into the pulse of modern life, like gold threads through cotton. And so, with brush and blueprint, curriculum and kiln, he helped stage a design renaissance that rewired Kyoto’s role from relic to beacon.

Right Man, Right Place, Right Time

By 1900, Kyoto’s status as Japan’s spiritual and aesthetic capital had been eclipsed by Tokyo’s growing power. But where others saw provincial stagnation, Sekka saw latent energy—a compressed archive of aesthetic intelligence waiting to be rerouted. He was a Kyoto native, fluent in both the imperial city’s decorative language and the rising grammar of industrial design. Crucially, he didn’t treat these as opposites. He treated them as collaborators.

Where Tokyo academies pushed toward yōga (Western-style painting), Sekka dug into the loam of Kyoto’s traditions and invited them to evolve. He understood the city’s artisan base—textile dyers, lacquerers, potters—not as craftsmen to be preserved, but as design collaborators who could innovate within their own languages. His interventions weren’t lectures. They were blueprints for transformation.

Evolution Through Education

One of Sekka’s sharpest tools was pedagogy. In 1904, he joined the newly established Kyoto Municipal School of Arts and Crafts (Kyoto Shiritsu Bijutsu Kōgei Gakkō). But his teaching wasn’t about technical replication. It was about rethinking structure. He trained students to see patterns not just as ornament, but as modular systems that could move across mediums: a pine motif on a kimono might also become a lacquered tray or a department store logo. This was not art education. It was cultural coding.

He taught design drawing and Rinpa-inspired aesthetics as forms of applied poetics—encouraging students to rethink traditional motifs as adaptable building blocks of modern Japanese visual identity. His classrooms became incubators, not of nostalgic replicas, but of experimental hybrids.

Simultaneously, Sekka took leadership roles in Kyoto’s artistic ecosystem. He was a founding member of the Kyoto Art Association (Kyōto Bijutsu Kyōkai) and helped revitalize the Kyoto Lacquerware Society, forging alliances between painters, craftsmen, and thinkers who understood that the future of beauty lay not in isolation, but in symbiotic evolution.

Breaking Down Barriers

The most radical thing Sekka did wasn’t stylistic. It was infrastructural. He dismantled the conceptual wall between “art” and “craft”—a wall propped up by Western hierarchies and colonial-era museums. In its place, he built a continuum, where a woodblock print could influence a tea bowl, and a kimono pattern could reshape a typeface.

He pushed painters to engage with utility, and craftspeople to think like artists. Through collaborative production guilds, Sekka seeded a system where form and function danced as equals. This wasn’t utopian idealism. It was calculated design strategy: ensuring that Kyoto’s aesthetic legacy would persist by becoming participatory.

From the late Meiji into the Taishō period, Kyoto’s creative networks evolved—not just in what they made, but in how they made it. Sekka wasn’t leading a movement. He was setting an algorithm into motion.

Collaborations

Nowhere was this algorithm more visible than in Sekka’s partnerships. In 1911, he co-founded the Kyōbuikai (京美会, “Kyoto Beauty Society”), a collective of designers, architects, potters, and craftsmen who saw in the past not a burden, but a design system. The group included Taniguchi Kōkyō and other Kyoto luminaries, and their goal was clear: fuse the artistic intelligence of traditional Kyoto craft with modern design methodologies drawn from Europe and the Americas.

The Kyōbuikai wasn’t a salon—it was a workshop, a lab. Ceramicists worked with painters. Lacquer artists learned from textile designers. Pottery forms were updated with Art Nouveau geometry, while surfaces retained Rinpa-inspired asymmetry and seasonal symbolism. Their exhibitions weren’t just showcases—they were proofs of concept that Japanese design could be both ancient and emergent.

Sekka’s role in this was not merely symbolic. He served as the design compass—mapping how legacy forms could mutate without disintegrating. His collaborations with figures like Asai Chū, another painter who walked the tightrope between Japanese and Western styles, pushed these boundaries further. Together, they produced lacquerware and textiles that fused Rinpa composition with modern design logic—objects that shimmered with both memory and momentum.

These weren’t trends. They were templates. Through Sekka, Kyoto became not a remnant of the past but a forward-facing archive, generating prototypes of cultural continuity. His fingerprints are not just on the artworks, but on the creative infrastructure that allowed them to flourish.

Legacy and Contemporary Perspectives

Kamisaka Sekka, Flower Wagon, (ca. 1910)

Some legacies fade into footnotes; Sekka’s detonates in slow motion. His art doesn’t echo—it recurs, mutates, surfaces in unexpected places. It haunts the negative space of a gallery wall in Kyoto, slips into the bevel of a tech accessory in Shibuya, breathes in the folds of a silk scarf in Paris. This is not afterlife. It is afterimage. The burn-in of a vision too architecturally sound to erode. Eight decades after his death, Sekka is not a reference. He is a system—a living index of Japanese aesthetic resilience.

His work is neither artifact nor antique. It’s blueprint. In every sector of contemporary visual culture—from exhibition design to packaging, from branding to textile innovation—Sekka’s modular grammar reemerges: bold silhouette, lyrical asymmetry, disciplined excess. In doing so, he rewrote the rule that tradition must bow to progress. Instead, he showed that tradition, like gold leaf, holds best when pressed into modern pressure.

Bridging Past and Present

Sekka is often hailed as the missing ligament between classical Rinpa ethos and modern Japanese design—but to call him a bridge is too passive. He was a load-bearing beam. The 20th-century graphic designer Tanaka Ikkō built directly upon his tension and simplicity, integrating Rinpa’s silhouette logic into visual systems for airports, fashion campaigns, and national branding. Tanaka’s 1992 Purple Iris panel at Narita doesn’t quote Sekka—it completes him.

Their kinship isn’t merely stylistic. It’s philosophical. Both understood abstraction not as subtraction, but as condensation—each line, curve, and pigment chosen for maximum mnemonic force. Sekka worked in mineral pigments. Tanaka in pixels. But the lineage is unbroken: both artists treated nature as syntax, tradition as semiotics.

Design scholars increasingly pair their names: Sekka as origin vector, Tanaka as amplification node. Their works don't just share lineage—they share function: to render cultural identity not as fixed form but as an evolving interface.

Museums and Scholars

Institutions have caught up. In 2003, the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto and the Birmingham Museum of Art co-hosted Kamisaka Sekka: Rimpa Master – Pioneer of Modern Design, a blockbuster exhibition that repositioned him not just within Japanese heritage but within global design history. That same act of repositioning—of recoding the decorative as structural—continues today.

The Panasonic Shiodome Museum’s 2022 retrospective, Inheriting the Timeless Rinpa Spirit, placed Sekka in direct conversation with his 17th-century predecessors, revealing not mimicry but mutation. Visitors didn’t see homage—they saw genetic evolution through brushstroke.

Contemporary artists—nihonga painters, graphic designers, fashion architects—now cite Sekka not as stylist but as system-builder. His influence shimmers in Murakami Takashi’s superflat forms, in kimono houses reviving Momoyogusa-style motifs, and in product designers embedding seasonal asymmetry into digital layouts.

In Kyoto, Sekka is still a native sunbeam. The Hosomi Museum holds one of the largest collections of his work, and his presence pulses through local craft markets, school curricula, and design ateliers. His aura is not relic. It is reference. It is functioning vernacular.

Cultural Identity and Tourism

Critics now place Sekka beside William Morris, not just for their love of ornament but for their militant insistence that beauty must inhabit utility. Like Morris, Sekka used pattern not to please the eye but to renegotiate the texture of daily life. Like Morris, he operated at the precise fracture between industrial scale and artisanal integrity.

Where Art Nouveau designers in France curled vines into iron and bone, Sekka coaxed chrysanthemums onto lacquer boxes, folding screens, and mass-printed books—each one a tactical reassertion that Japan’s visual intelligence needed no Western proxy.

His prints reside in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Freer Gallery in Washington. Not as curiosities. As anchors in the global story of design’s dialogue with memory.

Collectors prize first editions of Chigusa and Momoyogusa as more than woodblock masterpieces—they see them as algorithms: each page a modular engine of aesthetics, capable of being reassembled across centuries.

Kyoto knows what it has in Sekka. During the 2015 celebration of the 400th anniversary of the Rinpa school, his presence was ubiquitous: not just in museum vitrines, but on posters, tote bags, floor projections in department stores. This wasn’t kitsch. It was soft power, expertly deployed—Rinpa as civic branding, Sekka as cultural proof-of-concept.

Through Sekka, Rinpa became not just a lineage but a flexible aesthetic platform—a visual philosophy that could stretch across time zones, retail categories, digital devices. Kyoto’s identity as a city of living tradition owes as much to Sekka’s design logic as it does to its temples and tatami.

To see a Sekka-inspired tea tin in a boutique or a reinterpretation of his Flower Wagon in a Tokyo gallery is not to witness a copy. It’s to experience the endurance of a code—one that tells you you’re standing at the edge of something both ancient and immediate.

Sekka didn’t just make beautiful things. He made tradition contagious.

Conclusion

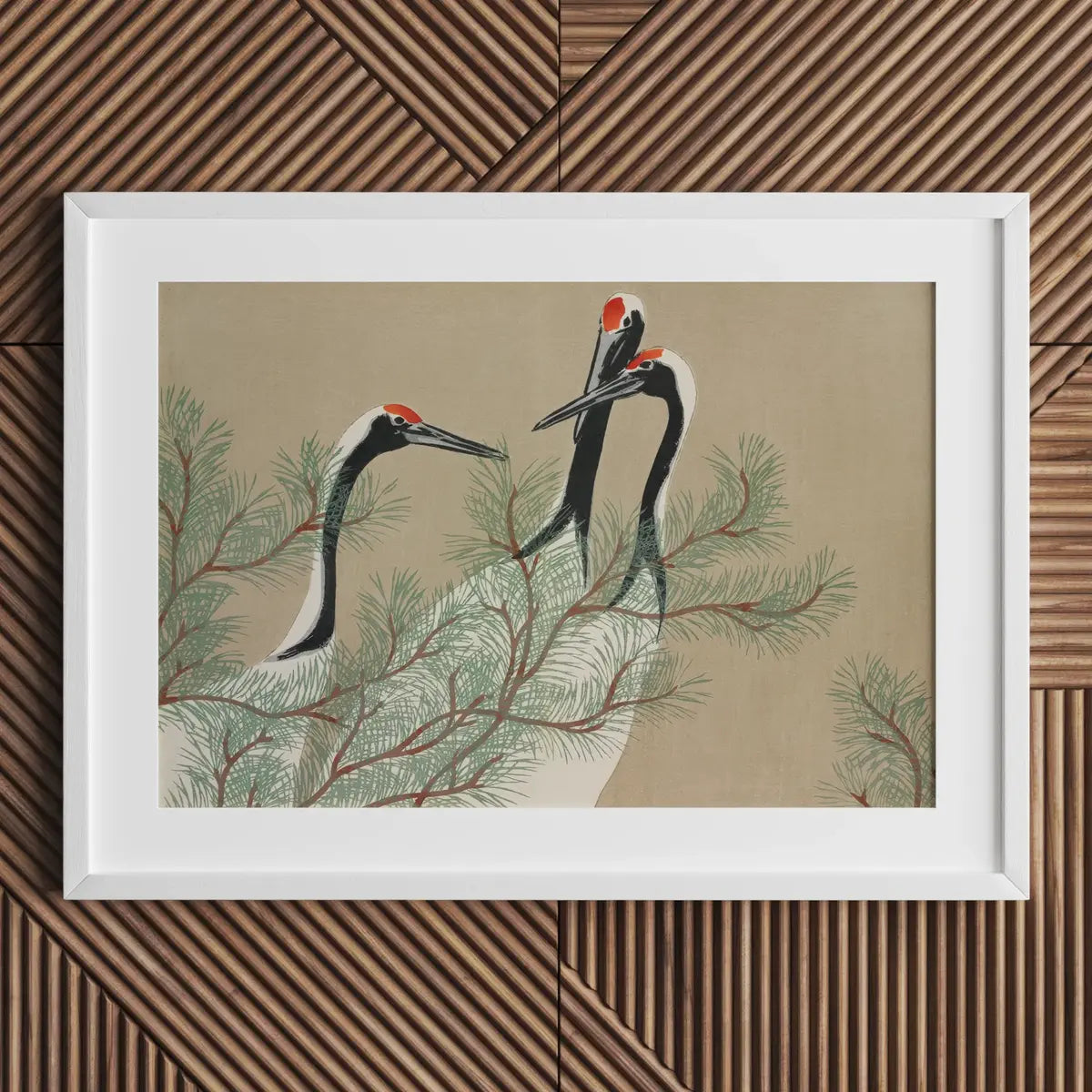

Kamisaka Sekka, Cranes from Momoyogusa, (ca. 1910)

Sekka did not walk a tightrope between tradition and innovation—he built the bridge beneath it, one lacquered plank at a time. His journey was not a stylistic evolution but a cosmological one: from inkstone to printshop, from the breathless hush of Rinpa scrolls to the bright cacophony of modern design. Born in Kyoto's twilight of swords and fanfolds, Sekka carved a visual language that would outlive the empires, galleries, and craft guilds that once housed it. He knew what most forget—that to preserve something is not to trap it in amber, but to teach it to move.

He once described the Rinpa master Ogata Kōrin as a “revolutionary of taste.” But Sekka was something more feral: not a revolutionary, but an engineer of memory—his works not declarations but schemas for regeneration. Through prints like Momoyogusa, lacquered half-moons, and iris-laced screens, he rescripted Japanese aesthetics as something migratory. A motif could shift shape, migrate mediums, rupture context—and still sing in the dialect of Kyoto.

His Momoyogusa cranes don’t fly—they glide between registers: painterly, poetic, graphic, sacred. Their geometry speaks not only of avian form but of modular composition. To turn one of Sekka’s pages is to open a portal—a choreography of pigment and pattern that invites not nostalgia, but reorientation. This wasn’t backward-looking. It was cartographic.

Standing before one of his folding screens today, the shock is not how old it feels—but how newly intelligible. The arrangement of chrysanthemums like typographic glyphs. The stream that breaks its own banks. The cloud not as vapor but as rhythm. These are not antiques. They are visual algorithms, replaying, recontextualizing, remapping.

Sekka’s project was never to protect the past. It was to keep it active, generative. In an age where cultural memory is flattening into content, his work reminds us: heritage is not data—it is method. His genius was not just in what he made, but in how he made memory move like water: held briefly, reshaped constantly, never lost.

So we return—again and again—to those lacquered silhouettes and luminous scrolls. Not to revere, but to recalibrate. Because Sekka proved the most radical gesture isn’t breaking from tradition. It’s plugging back into it—differently, deliberately, and with eyes wide open to the century yet to come.

Reading List

- Carpenter, John T., ed. Designing Nature: The Rinpa Aesthetic in Japanese Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012. (Exhibition catalogue)

- Dees, Jan. Facing Modern Times: The Revival of Japanese Lacquer Art 1890–1950. PhD diss., Leiden University, 2007.

- Enomoto, Erika K. The Soft Power of Rimpa: Tracing a Fluid Creative Practice Across Space and Time. MA thesis, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 2021.

- Hammond, J.M. “Kamisaka Sekka: Looking Forward, with an Eye on Tradition.” Artscape Japan (Panasonic Shiodome Museum of Art exhibition review), 2022.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Designing Nature: The Rinpa Aesthetic in Japanese Art. Exhibition Archive, 2012–2013.

- Walters Art Museum. Japanese Lacquer from the Meiji Era. Exhibition Catalogue, Baltimore, 1988.