Exploring the Impact of Famous Collage Artists Who Defined the Artform: From Dada to Feminism, the Harlem Renaissance, Matisse's 'Drawings with Scissors' and More…

Collage is not the art of cut and paste. It is the seduction of disruption. The poetry of paper sliced mid-thought, reassembled into defiance. It arrived not from the loins of modernism but centuries earlier—inked onto scrolls in 10th-century Japan, sewn into devotional fragments, hiding in plain sight. But don’t worry: Wikipedia already tripped over that rabbit hole. And plenty of others.

The artists gathered here—eleven shape-shifters with scissors for tongues—didn’t simply use collage. These famous collage artists seduced it. Shattered it. Laughed at it. Turning it inside out. Summoning its strange possibilities into new dimensions of beauty, queerness, satire, rage, seduction, protest. They didn’t define collage art as much as they exploded its entrails across the walls of politics, the flesh of feminism, the afterbeats of jazz and Weimar smoke.

We must, regretfully, address the definition of the definition. No, that wasn’t a typo. You live in a world where art historians kneel at the pews of Tate and Guggenheim, so you’ve heard the gospel: that modern collage began with Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque circa 1912, when they started glueing fake wood grain and newspaper scraps into their cubist works. Papier collé. Or, as I like to call it, artisanal sticker-shock.

Of course, there was collage before Cubism. And let’s be honest... their early collages? Not the finest. Even Picasso, patron saint of ego, wouldn’t post “Bottle of Vieux Marc” to his Instagram. No, these works survived because they were birthed by names that could bully permanence into history. Not because they were glorious. And yet—they are important. Not for perfection, but for permission. They cracked open the frame. They let the wrong things in. They made room for what came next.

That’s the real gift of those janky little cubist experiments: they marked the moment collage stopped being ornamental and started being philosophical. They whispered (okay, shouted): Art is no longer bound by brush or bronze or marble. Anything that can be taken apart can be made sacred.

Each of the eleven artists in this list brought collage to a new frontier. Political. Personal. Spiritual. Ugly. Dazzling. They built mythologies out of clippings. They turned scraps into sermons. They hacked history with a glue stick. And here, then, is your invitation to the scissors’ revolution.

You’re about to meet:

A Dadaist who sliced patriarchy with kitchen knives. A Harlem artist who chorused Black identity into layered refrains. A Frenchman who drew with scissors in his final decade and made the paper sing. A feminist typographer who commandeered mass media and made it scream back.

And me? I’m a collage artist too. Or a thief. Or a mirrorball. I cut up the internet and reassemble its shards into confessions. And I’ll admit: writing this, I didn’t know all my collaging compatriots. Not at first. And maybe you won’t either. That’s the point. Our paper trail is long. The archive crooked. But let’s follow it anyway. Just don’t expect it to be linear...

Famous Collage Artists Who Defined the Artform

1

Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch, Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany, 1919. Collage. 44 9/10 × 35 2/5 in | 114 × 90 cm.

...

Photomontage Pioneer. Political Saboteur. Visual Anarchist.

Hannah Höch didn’t cut with safety scissors. She wielded the blade like a scalpel, dissecting the cultural corpse of Weimar Germany and stitching it back together with wire, wit, and weaponized absurdity. Born in 1889 in Gotha and sharpened in the experimental furnace of Berlin’s pre-war avant-garde, Höch fused trained craftsmanship with radical disobedience.

A graduate of the Berlin College of Arts and Crafts and the Royal Museum of Applied Arts, Höch entered the arts as a graphic designer for women’s magazines. But she wasn’t interested in pretty things. She was interested in blowing up the ideology of pretty. Collage wasn’t her medium—it was her mode of resistance, a kind of bricolage that stitched together fragments from disparate realities.

The Work of Hannah Höch is Considered to be a Part of What Artistic Style?

Dadaism was less a movement and more a strategic breakdown—and Hannah Höch was its slyest saboteur. Her artistic style is rooted firmly in Dada, the post-WWI surge of aesthetic anarchy that eviscerated logic, nationalism, and bourgeois taste with absurdity and glue.

Her approach to hand-cut collage—what art historians now call “analog montage”—put her among the first artists to treat found imagery as raw material for visual protest.

But where her male contemporaries screamed chaos, Höch whispered it through scissors. Her pioneering use of photomontage—a technique that juxtaposed magazine cutouts, commercial ads, and political propaganda—turned mass media into feminist shrapnel. She dissected the world not to document it, but to rewire it—channeling gender subversion, queer visibility, and the “New Woman” ideal that electrified Berlin’s cabaret culture.

Höch’s work responded to Weimar-era gender constructs and cultural debris. The “New Woman,” mass-produced beauty, fascist iconography—she sliced them up and reassembled them into visions that were part satire, part prophecy. Her fragmentation of identity and reality later influenced postmodern collage and intersectional feminist art.

She didn’t merely participate in Dada. She expanded it. Höch challenged Dada’s own internal misogyny, exposing the boys’ club hiding behind the anti-art rhetoric. Her collages questioned authorship, authenticity, and the fetishization of originality long before postmodernism gave those terms a seminar.

Her influence echoes through contemporary collage, especially in the work of artists exploring hybridity and personal mythology.

In short: Dada was rupture. Höch was its scalpel.

She was the lone woman in a Dada boys’ club.

A movement drenched in nihilism and cabaret smoke, where chaos was both content and creed. Among male peers like Raoul Hausmann and George Grosz, Höch stood her ground and sliced deeper.

Her work wasn't just anti-authoritarian; it was anti-patriarchal, anti-nationalist, anti-aesthetic. She fought fascism with found imagery. Her materials were stolen from newspapers, fashion pages, mail-order catalogues, and war-time propaganda—visual refuse transformed into political collage as razor-sharp satire.

Her signature: a text-and-image fusion that weaponized the everyday.

Why Was the Dada Artistic Movement Important to Future Artists?

Because Dada didn’t just change what art looked like. It changed what art meant. It was the great aesthetic jailbreak—flinging open the gates of tradition and setting loose a thousand strange possibilities.

Born from the wreckage of World War I, Dada wasn’t a style. It was a strategy. A refusal. A sarcastic laugh thrown into the face of nationalism, moralism, and meaning itself. And future artists listened.

From Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain—a urinal signed “R. Mutt” and submitted to an art show—as an act of elegant vandalism, to performance art that would later erupt in protests, happenings, and guerrilla theater, Dada became a blueprint for rebellion. Art could now be a question. An interruption. A dare.

It Validated:

- Found objects as sculpture

- Wordplay as visual structure

- Chance as composition

- Absurdity as critique

Dada wasn’t about chaos for chaos’ sake—it was chaos as resistance. It refused polish, logic, and market-friendliness. It spat in the face of elegance and turned collage into combat.

Its children were many: Surrealism, Fluxus, Conceptual Art, Performance, Punk, Internet meme culture, and every political poster that ever cut a dictator’s head onto a Barbie doll. Even the idea that art could be an idea owes its shape to Dada’s jagged edge.

Techniques like décollage, assemblage, and the cut-and-paste technique all trace their roots to this radical DNA.

By mocking everything, Dada made it possible to question anything. And in that rupture, artists found not just liberty—but tools.

Art stopped asking, “What’s beautiful?” It started asking, “What’s true?” And Dada, ever sarcastic, ever necessary, grinned behind the glue.

Hannah Hoch's seminal work?

Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany (1919):

A sprawling, feverish photomontage nearly four feet tall

Choked with politicians, automatons, cabaret performers, and dismembered machinery

Organized like a battlefield—chaos staged with precision, commentary dressed as collage

Through this work, Höch took apart the bloated masculinity of Weimar politics and rebuilt a world teetering between progress and oblivion. The title alone is a provocation—the “kitchen knife” slashing through the “beer belly” of bloated empire. It’s both domestic tool and political blade.

Major Themes in Höch’s Work:

The “New Woman” as both subject and site of cultural anxiety

Collage as a critique of mass media and gender roles

Humor and grotesquerie as visual strategy

Branded degenerate by the Nazis, Höch went underground. She survived WWII in quiet defiance, preserving her practice in shadow while the world burned around her. Her influence radiates through later generations—from Barbara Kruger to Cindy Sherman, from punk zines to feminist meme culture.

Höch didn’t seek to document reality. She dismantled it. She made photomontage not just a tool of expression but a blueprint for ideological sabotage. What she cut, she remade. Her politically charged collage is sharp, funny, furious and unforgettable.

Reading List

- Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife on Smart History

- Hannah Hoch on The Art Story

- Hannah Hoch on Encycolpedia.com

- Hannah Hoch on Wikipedia

2

Romare Bearden

Romare Bearden, Empress of the Blues, 1974, acrylic and pencil on paper and printed paper on paperboard, 36 x 48 in. (91.4 x 121.9 cm.)

...

Harlem’s Storyteller. Jazz’s Visual Twin. America’s Collage Griot.

Romare Bearden didn’t paint scenes—he reconstructed them from memory, sound, and the fractured syntax of lived experience. Born in Charlotte, North Carolina in 1911 and raised amid the twin pulses of Pittsburgh steel and Harlem heat, Bearden was fluent in collage—modernist, narrative, figurative—long before he ever touched a pair of scissors.

Migration, jazz, and ancestral longing were already layered within him, weaving together the cultural inheritance of the African American experience and the Black American South.

What he did with printed paper, fabric, acrylic, graphite, and found imagery was a method of excavation, a layered surface built from magazine clippings, newspaper collage, textile collage, and painted collage.

As a Black collage artist immersed in the Great Migration’s rhythms and the Harlem Renaissance’s aftershocks, Bearden shaped a visual language that refused to separate the personal from the political, improvisational from the deliberate, or memory from history.

Educated at Boston University, NYU, and Columbia—where he studied under George Grosz—Bearden cultivated his aesthetic in the crosscurrents of social realism, jazz improvisation, urban realism, and Black art history.

As a Black American painter and muralist in 20th-century America, he didn’t create abstractions of struggle. He built its architecture—porches, city blocks, baptismal pools, brass bands, domestic rituals—reconstructed with cut-and-paste technique, collage as cultural archive, image juxtaposition, and the jazz structure of syncopated cuts and visual riffs.

His works stand as prismatic compositions, kinetic and lyrical, collages of Black migration, urban landscape, and spiritual mapping.

Key Materials and Techniques:

- Printed paper, magazine clippings, newspaper collage, fabric, acrylic paint, graphite, photomontage

- Overlapping silhouettes, rhythmic layering, improvisational structures, dynamic composition, bricolage

- Visual improvisation, narrative layering, fragmented imagery, spatial rhythm, text-and-image fusion

In works like Empress of the Blues (1974), you don’t just see a woman. You hear her. She moans from the paper’s grain, shoulders squared with grace and fatigue. Bearden’s collages hum with Afro-Atlantic spiritual density—a Southern church service spliced with subway static and trumpet calls, layered like a jazz ensemble. Every surface is crowded, not with clutter, but with history—Black family life, urban collage, communal memory, cultural hybridity.

Major Themes:

- Memory as communal inheritance, ancestry in art, personal mythology

- The Black American South and Northern urban diaspora, Harlem’s Black culture

- Jazz structure and improvisational spirit in collage, rhythm and blues, musical composition in visual art

- African American identity, the Great Migration, cultural crossroads of Black American experience

- Black spirituality, domestic rituals, city blocks as living history

Raised in a Harlem home that became a salon for thinkers and artists—W.E.B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, and others—Bearden witnessed the Harlem Renaissance from within, an observer of the Harlem arts activism that set the stage for the Black Arts Movement.

Bearden didn’t just inherit its legacy; he expanded it—collage as a political voice, a method of assembling fragmented Black identity into layered coherence. His collages speak of the African diaspora, of the improvisational spirit carried forward by contemporary collage practitioners who see collage as cultural commentary and jazz as visual language.

Bearden’s approach echoed the pulse of improvisational music—repetition with variation, syncopated cuts, visual improvisation across a single theme, dynamic composition. He said, “I try to show that when some things are taken out of context, they can still speak a truth.” He was speaking of photographs, found imagery, and newspaper clippings. He was speaking of the Black urban landscape and ancestral memory, cut into fragments and reassembled into spiritual blueprints.

Legacy Beyond the Canvas:

- Appointed first art director of the Harlem Cultural Council

- Co-founded Cinque Gallery and The Studio Museum in Harlem—institutions that championed African American art and Harlem’s Black culture

- Collaborated on set designs for Alvin Ailey’s American Dance Theater, extending collage’s improvisational structure into performance art

- Illustrated books, wrote plays, composed music—an interdisciplinary legacy of visual jazz and collage as performance

- The Romare Bearden Foundation, founded in 1990, supports contemporary collage artists and African American art scholars, amplifying his influence on future generations

But Bearden’s truest afterlife lives in every artist who collages from chaos—who dares to build coherence from fracture, to find personal mythology in bricolage, to turn layered surfaces into historical memory. Bearden didn’t depict Harlem or the African American experience. He translated them—improvisational, layered, kinetic—into spiritual blueprints and visual jazz, ever alive in the fragments and rhythms of collage art.

Reading List

- Empress of the Blues in American Art

- Harlem Renaissance on History.com

- Romare Bearden on Biography.com

- Romare Bearden on Brittanica.com

- Romare Bearden on Encyclopedia.com

- Romare Bearden on Holmes Art Gallery

- The Romare Bearden Foundation

3

Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse, Zulma, 1950. Gouache on paper. 108 x 60 inches.

...

Scissors in Hand. Color Unleashed. Art Reborn.

Henri Matisse didn’t fade quietly into old age. He ignited. When illness made painting arduous, he stood defiant—scissors in one hand and chromatic thunder in the other. His late-life works, the famed cut-outs, weren’t a farewell. They were a second adolescence. A riot of color born from gouache-painted paper, not pigment, pushing beyond the boundaries of collage art into a personal mythology of form and color.

He called it “drawing with scissors,” but what he really did was orchestrate color into motion—layered surfaces of hand-painted paper, cut and assembled like jazz riffs, improvisational and brimming with memory and archive.

In the 1940s, Matisse retreated to Vence in the south of France, body weakened but vision sharpened. Unable to stand at an easel, he turned to paper collage and mixed media collage, cutting with precision and abandon. He embraced the cut-and-paste technique, layering gouache-painted sheets in a process as immediate as jazz—liberated from the long rituals of oils and brushes.

His hand-cut collages weren’t an afterthought; they were a reinvention, rooted in the collage art techniques of the avant-garde but utterly his own. Matisse’s practice was tactile, engaged with the logic of dance, the boldness of stained glass, and the ephemeral yet permanent nature of layered paper art. These paper cut-outs embodied the full power of analog collage and the collage as cultural archive.

Why It Changed Everything:

-

Forged a new medium using scissors, gouache, hand-made process, and intuition

-

Rejected line in favor of color as structure, fusing visual improvisation with the tactile immediacy of collage art

-

Expanded abstraction while rooting it in organic shapes, floral motifs, and spiritual symbolism

-

Integrated the cut-and-paste technique with an emphasis on layering, overlapping, weaving, and integrating forms

-

Explored negative space use, compositional balance, and grid arrangement within a modernist montage

-

Embraced personal narrative and the ephemeral elegance of ephemeral materials—magazine clippings, vintage paper, found imagery, and ephemeral art transformed by the “drawing with scissors” process

Zulma (1950) is no still life. It’s a monument to sensual rhythm—standing 108 inches tall, cut into shimmering planes of color, stitched together like a hymn of joy and resistance. The figure is reduced but intensified, shaped from confidence and curve, an example of both figurative collage and abstraction. Matisse’s collage practice fused the figurative and abstract, playing with geometric cut-outs and organic forms, layered surfaces, and dynamic compositions—fusing the sensual and the spiritual in a single breath.

Core Themes in the Cut-Outs:

-

Movement over representation—echoing jazz structure and the improvisational spirit of collage

-

Joy as resistance—a bold testament to vitality and liberation through color

-

Nature reimagined through paper, breath, and the ephemeral cut

-

Exploration of positive and negative space, an interplay of transparency overlays and saturated color

-

Integration of organic shapes, dynamic composition, and the decorative arts into a new visual language

-

Celebration of simplicity through minimalist collage and maximalist color

-

Echoes of the Fauvist painter’s early experiments with color theory, recast through scissors, not brushstrokes

These weren’t sketches—they were final statements. Each pinned piece was alive with possibility, evolving in his studio like butterflies mid-transformation. The logistics of preservation became an art form in themselves: straight pins and tacks holding each cut-out in place, ephemeral compositions that captured the ephemeral nature of creativity. Today, conservationists still chase the ghost of his original compositions—torn paper art and hand-cut collage layered with quiet urgency and spiritual density.

These cut-outs would ripple across generations—Matisse’s influence visible in modernist montage, Abstract Expressionism, textile collage, digital collage, contemporary collage, and beyond.

From album cover art to street art collage, his bold shapes and vibrant color harmonies have helped shape the worlds of interior décor, editorial illustration, book cover design, fashion, and branding. Matisse's work would also go on to inspire digital manipulation, glitch art, AR collage, AI-generated collage, and meme editing—each a new generation’s echo of Matisse’s scissor-cut revolutions.

Matisse died in 1954. But in those final years, he remade modernism from a wheelchair—fusing cutting and layering, image juxtaposition, and the improvisational dance of collage. The cut-outs are not just images. They’re an entire philosophy of transformation and metamorphosis: personal mythology cut from gouache and breath, resilience and joy in every torn edge.

His legacy pulses in the children’s book illustration, in classroom projects and community workshops, in art therapy and in every hand-made collage that refuses to stay silent. Not despite limitations. But because of them.

Matisse’s art wasn’t just an act of creation. It was a revolution—of color, of spirit, of possibility—forever alive in the snip of scissors and the quiet thunder of chromatic paper.

Reading List

- henrimatisse.org

- Henri Matisse cut-outs on Wikipedia

- Henri Matisse cut-outs on moma.org - exhibition

- Henri Matisse cut-outs on moma.org - process

- Henri Matisse cut-outs on Wide Walls

- Henri Matisse cut-outs on YouTube

- Henri Matisse creating one of his cutouts

- How Matisse's cut-outs took over the illustration world

- How to Read a Matisse - The Met

- Conserving the Swimming Pool

- Zulma on moma.org

4

Barbara Kruger

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Your Body is a Battleground), 1989. Photographic silkscreen on vinyl. 112 x 112 in. (284.48 x 284.48 cm).

...

Typography’s Guerilla General

Barbara Kruger doesn’t ask questions. She interrupts them. An American artist, feminist artist, and conceptual artist—also a graphic designer, art activist, and postmodern provocateur—she has become an iconic voice of intersectional feminism in art.

Her work lands like a billboard in the brain—declarative, dissecting, demanding. Blending mass media critique with conceptual fury, Kruger transformed the flat language of advertising into a site of feminist collage, political collage, and protest art.

She pioneered a visual language of text-and-image fusion, graphic design collage, and subversive art—one that declared war on complicity and consumer culture.

Born in 1945 in Newark, New Jersey, she was raised on the twin screens of Catholic guilt and American television, absorbing the consumer culture ephemera and propaganda art of postwar America.

After studying at Syracuse and Parsons, Kruger landed at Mademoiselle magazine, where she swiftly rose to become chief designer. There, she learned to cut-and-paste power—juxtaposing, layering, and recontextualizing images into punchy slogans and bold typography.

She understood the graphic violence of advertising because she built it—cutting, tearing, layering, glueing, cropping, and fusing commodity with desire, assembling the architecture of capitalist critique.

But something snapped. She took that knowledge and reversed the current—splicing, weaving, and reconstructing the spectacle of mass media. Instead of feeding capitalism’s hungers, she starved it—using analog collage, digital manipulation, and found imagery.

She didn’t merely appropriate; she performed a Situationist détournement, weaponizing magazine clippings, newspaper collage, vintage paper, advertisements, and mail order catalogues.

Her bricolage aesthetic turned consumer culture’s own ephemera—comic books, receipts, text snippets—into site-specific installations and immersive installations that exposed the psychological violence of media and the blurred border between critique and complicity.

Signature Style:

-

Black-and-white photographs, recontextualized and cropped

-

Overlaid white-on-red Futura Bold Oblique or Helvetica Ultra Condensed—text-based art at monumental scale

-

Short, blistering phrases—punchy slogans that read like accusations or confessions

-

Cut-and-paste technique and text-and-image fusion, arranged in perfect compositional balance and grid arrangement

-

Juxtapositions that rupture the logic of consumer culture and gender politics—Kruger’s visual language as protest and political critique

Kruger’s aesthetic—once seen, never forgotten—is more than design. It’s conceptual art and feminist collage, avant-garde and agitprop. Her photomontage pioneer’s hand cuts through urban culture and capitalist mythologies, crafting street art collage that calls out to punk fanzines, queer collage, and the DIY aesthetics of underground resistance.

Her large-scale prints—often hand-made collages or digital collages—transform public spaces into stages of social commentary, disrupting mass media’s relentless pitch. If the personal is political, Kruger turns the ephemeral into the monumental—relief collage that becomes both personal narrative and collective outcry.

Famous Works That Burned Through the Canon:

-

Untitled (Your Body is a Battleground) (1989): A photo collage of a woman’s face—fragmented, layered, a split photomontage of photographic fragments and negative space. The phrase: “Your body is a battleground.” A feminist manifesto and cultural litmus test that fused image juxtaposition with political collage, gender politics, and anti-fascist art.

-

Untitled (I Shop Therefore I Am) (1987): A credit card brandished like a dagger—printed materials and found object art twisted into a consumerist creed turned existential crisis. Kruger didn’t just critique capitalism. She exposed it as theology.

Core Themes Across Her Oeuvre:

-

Identity and gender as constructs

-

The body as both commodity and battleground

-

The psychological violence of media

-

The personal mythology of power and language

-

The ephemeral and eternal of mass media critique

-

Memory and archive, nostalgia and trauma—woven together in her minimalist collage and maximalist interventions

Kruger’s work draws from feminist film theory, structuralism, postmodern philosophy, and the visual storytelling of editorial illustration—but never at the expense of legibility. Her photorealistic clarity collides with the poetic compression of text. Her photo collage and digital collage—often using Photoshop collage, scanning, and printing—are layered surfaces that refuse to whisper. They demand. Her art isn’t for the initiated. It’s for anyone with a gaze and a gut. She doesn’t make you decode. She makes you choose.

Long-Term Impact:

A foundational voice in the Pictures Generation, Kruger’s shadowbox collage and tape collage techniques have influenced generations of activists, designers, and conceptual artists. Her large-scale installations, site-specific installations, and collaborative collage projects continue to command museums, subway platforms, street culture, and editorial illustration.

Her work has become a cultural mashup—echoing urban collage, street art, contemporary collage, and even digital collage and AR collage. From magazine layouts to fine art collage, from gallery installations to the Instagram collage and social media content of today, Kruger’s legacy shapes the modern mythology of visual protest.

Barbara Kruger’s brilliance lies in compression. She distills whole ideologies into four-word ruptures—layered, ephemeral, yet monumental. Her work doesn’t whisper through gallery halls. It shouts from the scaffolding of culture itself, then asks why we were so quiet before—layering, weaving, and reconstructing the visual language of resistance.

Reading List

- Barbara Kruger in her own words

- Barbara Kruger on Artland

- Barbara Kruger on The Broad

- Barbara Kruger on jwa.org

- Barbara Kruger on moma.org

-

Barbara Kruger on Wikipedia

- Untitled (I Shop Therefore I Am)

- Untitled (Your Body is a Battleground) on The Broad

- The history of Untitled (Your Body is a Battleground)

5

Robert Rauschenberg

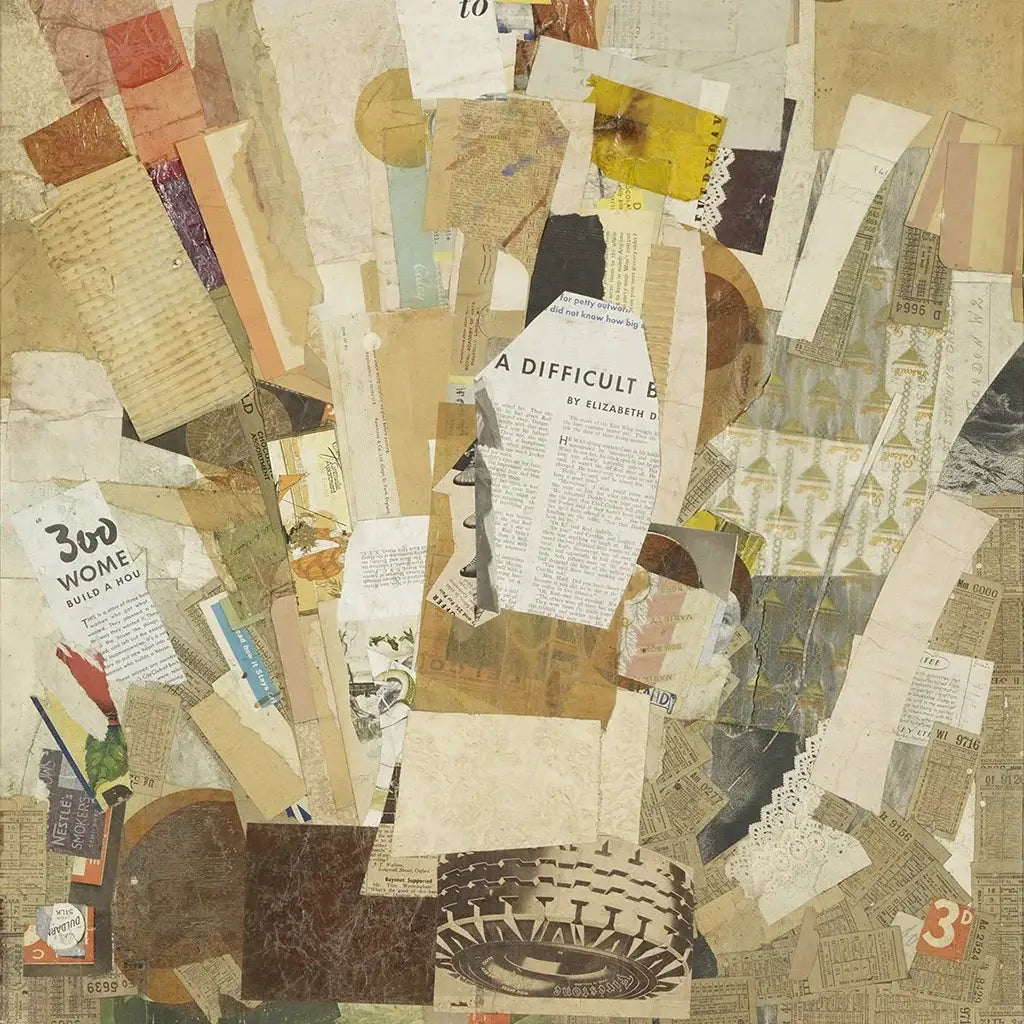

Robert Rauschenberg, Buffalo II, 1964. Oil and silkscreen ink on canvas

96 x 72 in. (243.8 x 183.8 cm.).

...

Robert Rauschenberg didn’t wait for permission to call garbage art. He canonized it. An American artist, modernist master, and pioneering collage artist, he was a postwar visionary whose bricolage aesthetic and subversive, anti-establishment ethos carved out a place for the avant-garde in the heart of consumer culture. A Neo-Dada icon and Pop Art precursor, he embodied the beat generation art spirit, remixing the world around him into a visual storytelling of fragmentation and memory.

Where others saw refuse, he saw resonance—found object art transformed by layering, cutting, tearing, and recontextualizing. A cardboard box? A time capsule of urban culture. A flattened tire? A chorus line of consumer culture’s poetry. His assemblage and relief collage compositions were text-and-image fusion long before the digital cut-and-paste age.

Rauschenberg was less a painter than a cultural provocateur, weaving spiritual symbolism and personal mythology into hand-made collage and analog collage pieces that redefined the boundaries of modernist montage and contemporary collage.

Born in Port Arthur, Texas in 1925, Rauschenberg took a serpentine route through art school—studying in Kansas City, at the Académie Julian in Paris, and eventually at Black Mountain College under Josef Albers. But it wasn’t Bauhaus rigor that shaped him—it was rebellion.

Black Mountain College’s collaborative making and Fluxus spirit—its avant-garde improvisation—ignited his art activism and playful, subversive approach. There, the grid arrangement and compositional balance of Bauhaus influences collided with the chance operations of street culture, forming the layered surfaces and textural contradictions that defined his work.

What Rauschenberg Did Differently:

-

Merged painting, photo collage, photomontage, and sculpture through “Combines”

-

Embedded real-world ephemera—magazine clippings, photographs, comic books, newspaper collage, vintage paper—into high-art spaces

-

Used layering transparencies, xerox transfer, image appropriation, and acrylic gel medium to forge new hybrids of found imagery

-

Transformed advertisements, packaging, postcards, ticket stubs, and wrapping paper—ephemera art of the street—into subversive political critique

-

Foretold Pop Art’s obsession with mass culture without succumbing to irony—he didn’t just sample; he remixed, spliced, wove, and integrated the collective memory and archive of a nation

His Combines—half-canvas, half-construction—defied categorization. They were mixed media collage, textile collage, hand-cut collage, and surreal overlays of the everyday. They embodied the anti-bourgeois, anti-art, Situationist détournement of their time, layered with humor and nostalgia, raw and ephemeral, yet monumental in their maximalist aesthetic. These weren’t simply mixed media. They were collisions—urban collage and psychedelic art turned into chaotic, ordered, layered, painterly visual storytelling.

Buffalo II (1964), created with oil and silkscreen, showcased Rauschenberg’s collaborative collage ethos and art as activism. JFK’s face, Coca-Cola logos, fighter jets, and ephemeral materials jostle for space in a saturated blur of national identity—a cultural mashup that defies easy interpretation. The piece is less a composition than a political hallucination, an urban dreamscape of postwar America’s capitalist critique.

Materials that Became Rauschenberg’s Vocabulary:

Newsprint, photographs, oil, fabric, taxidermy, tape, pins, staples, discarded objects, scraps of city life—ephemera reborn in his studio’s chance operations. He layered, overlapped, cropped, and deconstructed these fragments, using glue and scissors and the improvisational dance of arrangement and assemblage to create relief collage that vibrates with visual and cultural weight.

Recurring Themes:

The porous boundaries between art and life, urban life and personal narrative, fragmentation and metamorphosis. His work is a dance of improvisation—layering, sampling, remixing, and chance. It’s also a testament to the idea of recycling and transformation—turning ephemeral junk mail and sheet music into enduring modern mythology.

Rauschenberg rewrote the rules of art not with theory, but with gumption. He erased a Willem de Kooning drawing just to see if he could—transforming the act of destruction into a performance of resistance. He co-founded Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) in 1966, a visionary interdisciplinary creator bridging artists with engineers long before Silicon Valley’s digital manipulation and glitch art took the stage.

His collaborations with choreographers like Merce Cunningham turned performance into living collage—bodies as ephemeral, ephemeral fragments woven into ephemeral, ephemeral time. He was a spiritual descendant of Situationist détournement—cutting, tearing, and rearranging the world’s static noise into kinetic possibility.

Long-Term Influence:

Rauschenberg’s art foreshadowed the Pop Art collage of Richard Hamilton, the postmodern cut-up of Barbara Kruger, and the personal mythology of David Wojnarowicz. His ephemeral experiments with image juxtaposition and shadowbox collage shaped the contemporary collage of today. Rauschenberg created a blueprint for collage as protest, poetry, humor, resistance—an archive of popular culture that refuses to sit still.

Branden W. Joseph wrote that Rauschenberg's art acted as stimulus, not sermon. His pieces aren’t tidy arguments. They’re provocations—dense, layered, and open-ended, raw and spontaneous, yet harmoniously discordant. They’re playful, surreal, and graphic, each one a photorealistic hallucination of a culture caught in mid-collapse.

Rauschenberg made mess a virtue. His art said: Here is the world—fragmented, ephemeral, layered, and alive. Now what will you do with it?

The studio wasn’t separate from the sidewalk. The materials weren’t neutral—they were loaded with urban grit and collective memory. And Rauschenberg, ever the disobedient archivist, built a practice out of saying yes to everything: motion, noise, fracture, glue. He didn’t illustrate a culture. He jammed it through a screen, let it drip in layered transparencies, and called it now.

Reading List

- The Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

- Robert Rauschenberg on the Art Channel

- Robert Rauschenberg on Christie's

- Robert Rauschenberg on Gagosian

- Robert Rauschenberg on moma.org

- Robert Rauschenberg on MOCA

- Robert Rauschenberg on Nowness

- Robert Rauschenberg on tate.org.uk

- Robert Rauschenberg on Wikipedia

-

Buffalo II on christies.com

6

Kurt Schwitters

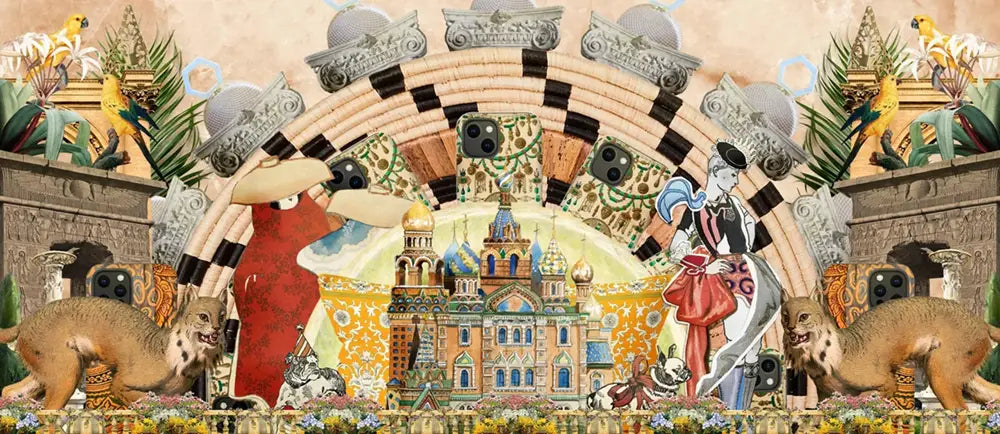

Kurt Schwitters, Difficult, 1942-43. Collage. 31.25 x 24 inches (79.37 x 60.96 cm).

...

The Patron Saint of Leftovers

If Dada was a howl, Kurt Schwitters was its echo trapped in a cigarette carton. German artist, avant-garde visionary, Dada pioneer, and modernist master, Schwitters was a true iconoclast and Merz artist. He didn’t scream anarchy. He whispered it with old tram tickets, candy wrappers, vintage paper, and shoe polish labels.

Born in 1887 in Hanover, Germany, Schwitters was a multimedia experimenter and cultural provocateur, who transformed collage into both poetic ritual and social commentary. His legacy as painter, sculptor, printmaker, graphic designer, typographer, poet, and installation artist remains vital to the story of postwar European art.

Schwitters took collage out of political protest and into existential architecture, blending paper collage, mixed media collage, analog collage, photomontage, and found object art with painterly brushstrokes and chance operations. Where others saw a pamphlet or a torn receipt—magazine clippings, vintage postcards, or recycled paper art—he saw structural integrity. He saw personal mythology and spiritual symbolism. He saw poetry.

Schwitters invented his own movement: Merz, a nonsense word snatched mid-syllable from "Kommerzbank." Merz wasn’t just a style, it was a bricolage aesthetic, a belief system for post-war survival. His Merzbau—the Merz cathedral of dreams—embodied this spirit: a 3D collage of urban life, art brut, folk collage, DIY aesthetics, mail art, and the archive of modernist montage.

The idea was simple: if the world had been smashed to pieces by artillery, inflation, and ideology, then art had to start from rubble. Beauty, for Schwitters, was born in the bin. Reconstructed from fragmentation, layered surfaces, and the ephemeral textures of cultural detritus.

Key Features of Merz:

-

Constructed from refuse, printed ephemera, and found imagery

-

Layered, tactile bricolage—assemblage and relief collage woven into a tapestry of improvisation and memory

-

Aesthetic of chaos made methodical—negative space use, transparency overlays, and the grid arrangement of everyday discards

-

Juxtaposition of newspaper collage, magazine collage, postcards, photographs, advertisements, fabric scraps, and discarded packaging

While the Berlin Dadaists were launching manifestos like molotovs, Schwitters worked alone in a quiet northern city that barely tolerated him. Berlin Dada’s noise met the silent, spiritual symbolism of his Merz practice. A fusion of anti-art provocation and cultural mashup. Schwitters didn’t shock for the sake of subversion. He was reconstructing, weaving and integrating. Like a mason of memory and archive. Using layered surfaces, text-and-image fusion, and hand-cut collage fragments.

Difficult (1942–43) exemplifies this ethos: a tactile montage of torn paper art, textiles, fabric collage, and shadowbox collage that holds together through layering, splicing, and fusing. It’s intimate, spontaneous, and quietly confrontational. It asks no questions. It simply insists on being there. Organic, graphic, painterly, and ephemeral all at once.

Why Schwitters Mattered:

-

Bridged Dada collage and Constructivist collage, merging them with radical empathy

-

Reclaimed the dignity of discarded material—upcycled art, repurposed materials, and ephemeral fragments from urban culture

-

Prefigured installation art, minimalism, Neo-Dada, Pop Art collage, and contemporary collage

-

Invented a form of collaborative collage in the Merzbau—Chance operations, improvisation, and the play of cultural mashup

-

Merged avant-garde protest art with poetic collage, crafting visual storytelling of personal mythology, transformation, and resistance

He didn’t stop at collage. Schwitters’ Merzbau—part cathedral, part hoarder’s hallucination—was Gesamtkunstwerk for the disillusioned. Columns of cardboard, thread and yarn, wrapping paper, wallpaper, sheet music, receipts, ticket stubs, and ephemeral dreams spiraled like a living archive of postwar European trauma and rebirth. It was a Situationist détournement of bourgeois order. A deconstructed, patchwork reliquary for a world in metamorphosis.

Fleeing Nazi persecution, Schwitters moved through Norway and eventually to England, where he was interned as an enemy alien at Hutchinson Camp. Even there, he continued working. Hand-made collage and small-scale Merz works layered with postal envelopes, comic books, children’s books, art catalogs, calendars, markers, pins, tape, and mail order catalogues. His internment cell became a workshop of personal narrative, trauma, and the ephemeral beauty of survival.

A collaborative maker and art world provocateur to the end, Schwitters had created over 8,000 works by the end of his life. Only a fraction survive, but his ephemeral, ephemeral practice of improvisation and assemblage lives on in every artist who sees the fragment not as refuse, but as a dreamscape waiting to be remade.

Legacy and Influence:

-

Inspired Robert Rauschenberg, Jessica Stockholder, John Stezaker, and countless others who explored abstraction, hybridity, and urban collage

-

Helped redefine collage as not just composition, but philosophy—a manifesto of recycling, transformation, and social change

-

Paved the way for modern craft, postmodern cut-up, street art collage, urban collage, and glitch art reinterpretations

-

Proved that ephemera—stamp collage, sticker layering, bricolage—could outlast empires and remake popular culture itself

Schwitters never sought belonging. He built his own world from the parts nobody wanted. His genius wasn’t in defiance alone. It was in accumulation, recontextualizing the everyday into visual and spiritual revelation. He didn’t collage for provocation. He collaged because there was no other way to make sense of the ruins. A patient, spontaneous act of layered, vibrant, and experimental transformation.

To encounter a Schwitters piece is to witness patience disguised as chaos—a poetic geometry of fragmented temporality. He didn’t fix the world. He rerouted its debris into a logic only the truly awake can read. Layered, harmonious, discordant, maximalist and minimalist, a subversive, witty, and tender invocation of art’s enduring mystery.

Reading List

- Kurt Schwitters on Wikipedia

- Kurt Schwitters on Artnet

- Kurt Schwitters on Retroavangarda

- Kurt Schwitters Interned

- Kurt Schwitters' Fascinating Found Objects

- Kurt Schwitters' Exhibition Tour at Berkeley

- Kurt Schwitters Documentary

- Difficult on Buffalo AKG

- Merz on Wikipedia

7

Eduardo Paolozzi

...

The Engineer of Pop’s Mad Machinery

Eduardo Paolozzi, the Scottish artist, British Pop Art pioneer, and multimedia experimenter, was a human Xerox machine with a philosopher’s wiring and a sci-fi collector’s appetite. Born in 1924 in Leith, Edinburgh, to Italian immigrants, this modernist master, cultural provocateur, and avant-garde visionary became a pioneering collage innovator. With a career spanning from printed ephemera to monumental sculptural work. An art activist and icon of urban collage, Paolozzi reimagined the world through a bricolage aesthetic that was equal parts gritty and glittering.

Paolozzi experimented widely with collage. From photomontage to analog cut-and-paste techniques, blending magazine ephemera with newspaper clout. And they didn’t dazzle with surface sheen... they short-circuited it.

Paolozzi recontextualized the language of consumer culture, fusing it with found object art, sticker layering, and torn paper art to reveal a world of absurdity and utopia, memory and archive. His practice was a mad alchemy of image transfer, relief collage, image juxtaposition, and surreal overlays—layered surfaces arranged in spontaneous, chaotic mosaics of the postwar British experience.

He wasn’t interested in nostalgia. This conceptual impresario and modernist maverick was obsessed with what came next. His early works were an unruly cocktail of mass media critique, surrealist collage dreams, and mechanical precision—vintage paper and advertising ephemera spliced into compositions that glowed with political critique and personal mythology. Found imagery, fabric scraps, and repurposed materials became the raw data of a cultural mashup—transforming junk mail and comic books into the poetic collage of Cold War anxieties.

Core Elements of Paolozzi’s Style:

-

Juxtaposition of American consumer imagery with British skepticism and social commentary

-

Integration of commercial prints, cybernetic motifs, and urban culture in an anti-art, anti-establishment aesthetic

-

Cut-and-paste technique that oscillated between mechanical precision and conceptual disruption, weaving fragmentation, layering transparencies, and grid arrangement into visual storytelling

In Wittgenstein in New York (1965), Paolozzi doesn’t illustrate the Austrian philosopher. He deconstructs him with digital collage foreshadowings—like an analog-to-digital prophet—layering compositional balance and negative space to create a dreamscape of memory and perception. It’s not homage. It’s transformation—fusing the body of the city with the metaphysics of the mind.

Recurring Themes:

-

The uneasy seduction of American pop culture and the surreal, spiritual symbolism of urban life

-

The liminal zone between humanism and mechanization, a hybrid identity of man and machine

-

Art as activism and personal narrative—dystopia reimagined through comic books, postcards, and ephemeral media

-

Humor and resistance channeled through punk fanzines, DIY aesthetics, and Situationist détournement

Paolozzi’s practice moved far beyond paper collage and photomontage. As a sculptor and graphic designer, he carved aluminum gods for the urban mythology of modern cities. His mosaics at London’s Tottenham Court Road station fused industrial detritus with the painterly, patchwork energy of street art collage and architectural collage. There, the subway became a motherboard, and passengers, unwitting data packets in a digital dreamscape of layered fragments and psychedelic art memories.

He viewed collage—bricolage and upcycled art alike—not as a technique, but as a worldview. The world was already a collage: humans, machines, empires, and fictions layered atop one another, pixel by pixel, cog by cog, fragment by fragment.

His methods—cutting, tearing, layering, glueing, montage, juxtaposing, pasting, overlapping, splicing, remixing, reconstructing—captured the liminality of cultural alterity and the spiritual symbolism of everyday debris.

Lasting Contributions:

-

Co-founded the Independent Group, precursor to British Pop, merging personal mythology and consumer culture in a collaborative collage ethos

-

Created pioneering screenprints and digital collage prototypes that anticipated digital manipulation, glitch art, and vaporwave aesthetics

-

Sculptural works that fused ancient myth with modern craft and street culture, weaving personal narrative into public space

-

Reframed collage as a cutting-edge postmodern cut-up—a deconstructed, maximalist critique of capitalist mythology and visual storytelling

Eduardo Paolozzi made visual philosophy from surplus catalogs and industrial scrap—art as a resistance, recycling, and reawakening. His collages and sculptures were not decorative—they were diagnostic. A glitch report on late capitalism, a cultural critique of ephemeral dreams, a love letter to the fragment’s power. His art was a hymn to the layered, ephemeral, and chaotic beauty of the contemporary, subversive, and visionary.

Where others celebrated Pop’s glitz, Paolozzi revealed its rust. In that corrosion, he found the seeds of a hybrid, transformative modern mythology—an art that could survive the future it feared and still find poetry in the ruin.

Reading List

- Eduardo Paolozzi on Wikipedia

- Eduardo Paolozzi on Artlex

- Eduardo Paolozzi on The Art Story

- Eduardo Paolozzi on Artnet

- Eduardo Paolozzi on the National Galleries of Scotland

- Eduardo Paolozzi Pioneers Pop Art

- Eduardo Paolozzi's Tottenham Court Road Mosaic

- Eduardo Paolozzi by Phil Jupitus

- Wittgenstein in New York on tate.org.uk

8

Martha Rosler

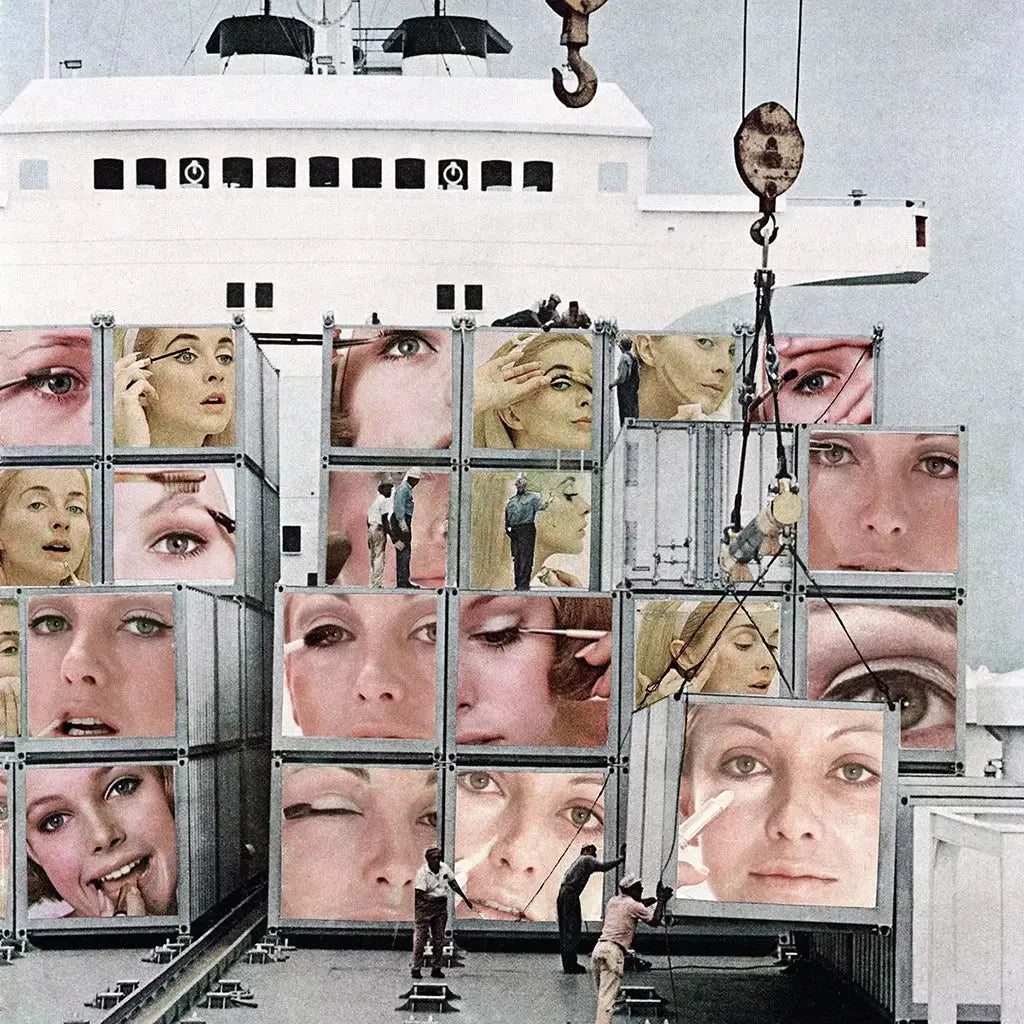

Martha Rosler, Cargo Cult, from the series Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain, 1966–72. Photomontage printed as photograph. 39 1/2 x 30 1/4 in.

...

The Kitchen as War Room, the Magazine as Weapon

Martha Rosler didn’t critique mass culture from a distance—she flayed it from within, blending protest art and social commentary into an avant-garde arsenal.

Born in 1943 in Brooklyn, Rosler became a feminist artist, political artist, conceptual artist, and cultural critic all at once—a multimedia experimenter who saw the kitchen as a site of political conditioning and the magazine as a war room.

She emerged as a collage innovator. An icon of protest art and agitprop. Weaving feminist collage, Pop Art collage, and postmodern montage into a subversive practice of intersectional feminism and capitalist critique.

Her materials? Everything mass culture spits out—magazine clippings, newspaper collage, vintage papers, found imagery, and ephemera. All stitched together in photomontage, analog collage, hand-made visions, and digital explorations.

Rosler mastered the photomontage, but her work pulsed with image appropriation, text-and-image fusion, bricolage, upcycled art, sticker layering, surreal overlays, layering transparencies, and repurposed materials. Cobbled together in an arsenal of processes: cutting, tearing, layering, glueing, arranging, remixing, splicing, weaving, fusing, deconstructing, digital manipulation, analog and digital transformation.

Her Key Tool? Photomontage

Rosler’s photomontages were never decorative. They were post-Internet art before the term existed—DIY aesthetics turned into coded documents, urban collage born from recontextualizing domestic critique and gender politics.

She used graphic design collage and literary collage to build visual storytelling that married personal mythology with modern mythology.

In Cargo Cult from Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain (1966–72), she juxtaposed advertising’s polished femininity with brutalist mechanical insertions—surreal, layered, and subversive.

And the absurdity wasn’t whimsical. It was systemic—an art brut of transformation and trauma, resistance and humor, a testament to memory and archive.

Major Themes in Rosler’s Work:

- Domestic spaces as sites of gendered battlefields.

- The female body reframed through protest and identity.

- Urban life, consumer culture, and media complicity, layered into personal narrative.

In Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975), a minimalist yet maximalist performance, Rosler—channeling collage as performance—names utensils with deadpan force: “grater,” “ice pick,” “ladle”—each a weapon of wit and social change. Her grid arrangement and compositional balance built a new language from domestic tools.

Why Rosler Still Matters:

Martha Rosler stands as a pioneer of feminist conceptual art—an icon of urban activism and intersectional feminism. She helped forge the voice of contemporary collage, graphic and painterly, ephemeral yet raw. Her practice is a modern craft of social change, a bricolage aesthetic for a world of multiplicity and liminality. Her influence lives in every visual protest that deconstructs power. Echoed in Punk zine collage, collaborative collage, Fluxus experimentation, and the mail art movement.

Rosler’s installations and photojournalistic collage transformed personal mythology into political critique—poetic and cutting-edge, deconstructed yet harmonious. She rejected the polished veneer of the art world, preferring community halls and street culture to galleries. Yet her layered surfaces and image juxtaposition made her an art world icon, inspiring urban collage, street art collage, and the global movement of protest art.

To encounter Rosler’s work is to feel implicated. With no safe haven or easy answers. Her art doesn’t just expose the world’s fractures. It stitches them into a collective vision and perception, spiritual symbolism and the unconscious. An experiment in seeing, and in being seen.

Reading List

- martharosler.net

- Martha Rosler on The Art Story

- Cargo Cult at the AGNSW

- Martha Rosler on tate.org.uk

- Martha Rosler on Wikipedia

9

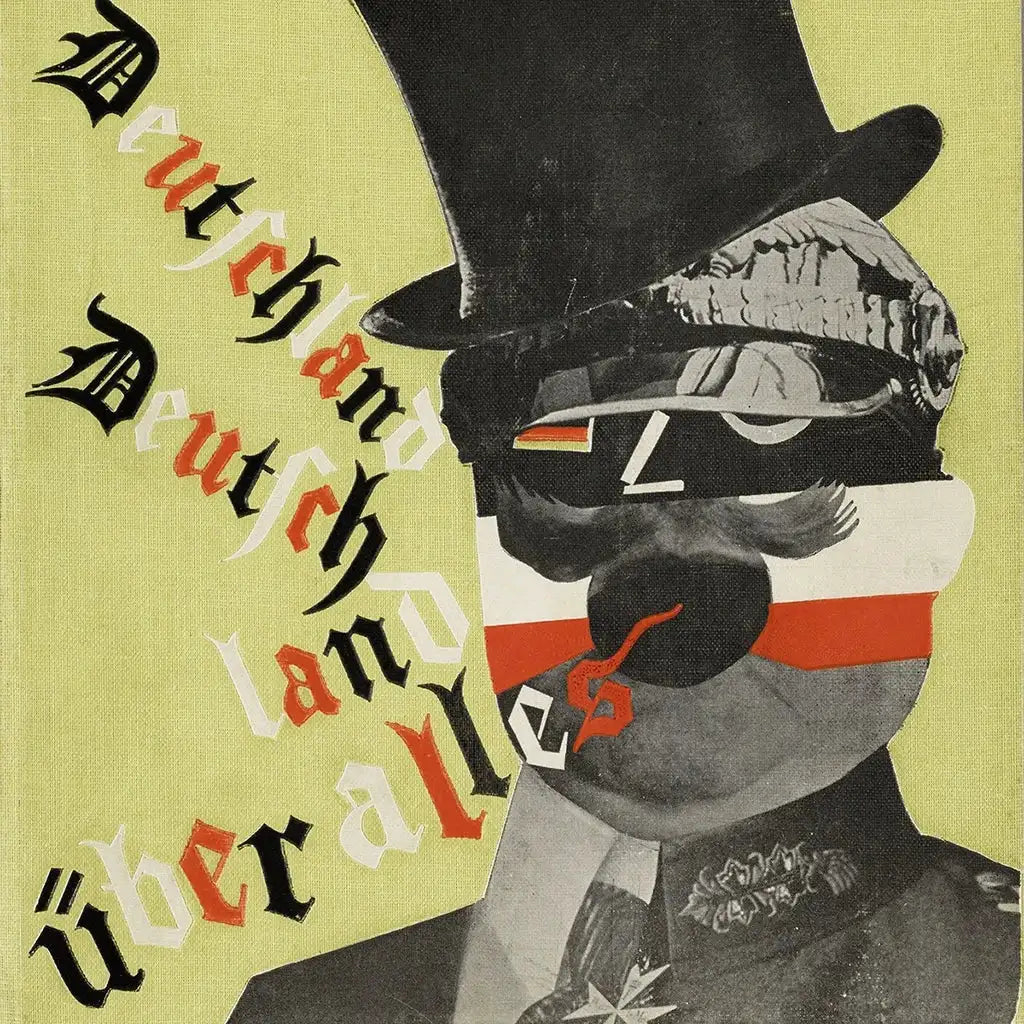

John Heartfield

John Heartfield, Cover art for Kurt Tucholsky, Deutschland, Deutschland über alles, 1929 © The Heartfield Community of Heirs / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020 Akademie der Künste, Berlin.

...

Cut-and-Paste Resistance, Printed in Blood

John Heartfield didn’t collage for aesthetic pleasure—he collaged like a man barricading his front door with furniture while the boots echoed closer.

Born Helmut Herzfeld in 1891, this Dada collage pioneer and avant-garde visionary Germanized his name into a protest—anglicizing it as “John Heartfield” during World War I to declare his rejection of German nationalism. Even his name was a montage, a bricolage aesthetic of identity and resistance.

A photomontage visionary, Heartfield weaponized the printing press against tyranny. His political collage work combined paper, magazines, newspapers and ephemera. Wielding found imagery and archival collage like shrapnel.

While Dada collage flickered with surreal chaos, Heartfield forged its cousin: militant montage, sharp as a guillotine and twice as fast. He wasn’t aiming for ambiguity. He was aiming to wound the authoritarian image with its own reflection.

The Battlefield Was the Page

From 1930 to 1938, Heartfield designed over 240 politically loaded montages for the leftist Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (AIZ). Each one a visual grenade lobbed at Hitler, capitalism, militarism, and hypocrisy.

His mixed media collage works—cutting, tearing, layering, glueing, and pasting—were editorial illustration turned into protest art. His photomontages? Political critique, agitprop, and social commentary built from whatever he could find. They were printed, smuggled, and circulated across Europe in a time when paper was as dangerous as bullets.

In his searing cover for Deutschland, Deutschland über alles (1929), a monstrous German bourgeoisie sits atop a pile of corpses—cigarette drooping from mouth, eyes glazed with arrogance. No symbolism. Just savagery.

Hallmarks of Heartfield’s Practice:

Meticulous image manipulation before Photoshop existed, of course. And Heartfield was an analog master of image transfer, image appropriation, and transparency overlays. Deploying photomontage as mass communication, not gallery ornament. Using satire to dissect propaganda with surgical precision.

He composed with scissors, tape, pins, and glue, but thought like a war correspondent. Each image was a fragmented, layered code—meant to be read, not simply seen. Irony sharpened into urgency. Each montage a visual storytelling of absurdity, humor, and political subversion.

Iconic Themes:

- Anti-fascism and state critique

- Deconstruction of Nazi iconography

- The image as political weapon, not passive document

Heartfield’s montages weren’t confined to metaphor. They were intercepted, banned, hunted. The Gestapo wanted him silenced. Exhibitions were raided. His life was in constant flight—from Berlin to Prague to London. But exile did not blunt his edge. He continued producing collaborative collages for theater, publishing, and political movements abroad, becoming a graphic design icon in the process.

Legacy Across Time and Borders:

Heartfield will forever be remembered as a cultural critic whose agitprop collage innovation directly influenced political art movements across the Eastern bloc and beyond. A visual forefather to artists like Martha Rosler, Winston Smith, and David King, Heartfield’s avant-garde protest art techniques inform punk zines, anti-bourgeois satire, and viral protest imagery today.

He showed that the cut-and-paste technique—this deconstructed, raw, organic form of found object art—could be as fierce as any slogan. His political collages didn’t hide behind abstraction. These montages spoke plainly in the language of fragmentation and resistance. He used the tools of compositional balance—grid arrangement, overlapping, juxtaposing, fusing, and weaving—to turn propaganda art against itself.

Today, when memes destabilize governments and photomontage rides the algorithm, Heartfield’s Weimar Republic art legacy pulses beneath every jpeg soaked in cultural critique. He didn’t create art for contemplation. He created it for the fight. In every layered surface, he asked: What will you do now that you’ve seen this? And what will it cost you if you look away?

Reading List

- johnheartfield.com

- Deutschland, Deutschland über alles

- John Heartfield on The Art Story

- John Heartfield at the Getty

- John Heartfield on Encyclopedia.com

- John Heartfield on Open Culture

- John Heartfield's biography by his grandson

- John Heartfield on Wikipedia

10

Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso, The Bottle of Vieux Marc, 1913. Cut-and-pasted printed wallpapers, newspaper, charcoal, gouache, and pins on laid paper, 24 13/16 × 19 5/16 in. (63 × 49 cm).

...

The Collage That Didn’t Want to Be Famous AKA: Which artist made the concept of collage into a form of art in 1912?

Pablo Picasso didn’t invent collage. But he cracked it open like a safe. A Spanish artist, cultural provocateur, 20th-century art legend, and modernist master—Picasso, alongside Georges Braque, co-created Cubism. And in 1912, they pioneered the radical anti-art of Cubist collage. Picasso's cut-and-paste technique, at once painterly and sculptural, redefined what art could hold.

He was a pioneer and avant-garde icon whose practice of layering vintage paper, magazine collage, newspaper collage, found imagery, fabric collage, and advertisements on canvas birthed the first truly modern mixed media work. Repurposing newspapers and fabric scraps to bridge high and low culture. Practicing the early stages of image appropriation and text-and-image fusion.

In Still Life with Chair Caning, Picasso layered newspaper collage with oilcloth and a rope border, performing a geometric cut-out that snatched the image out of illusion and into gritty materiality.

This wasn’t just painted collage. It was bricolage. A Cubist collage of shattered perspectives and urban life, an upcycled art born from the ephemera of modernity.

In these works, image juxtaposition was everything: a hybrid of abstraction and figuration, of memory and popular culture references, of personal mythology and cultural mashup. A fragment here, a trace of nostalgia there. A bottle of Vieux Marc flattened into a rebellious geometry.

Picasso’s layering was both a dreamscape and a resistance. Layered surfaces of ephemeral materials that mocked the supposed harmony of academic painting. The newspaper and wrapping paper scraps he used became social commentary, a protest of bourgeois decorum, a graphic collision of urban culture and political critique.

He glued, tore, overlapped. Recontextualizing and reconstructing images into visual storytelling that broke from the past.

His compositions were exercises in chance operations and improvisation, the grid arrangement of Cubist collage morphing into the raw, playful, and subversive patchwork of modern mythology. With magazine collage and torn paper art, he turned the picture plane into a site of protest art—layered, discordant, raw.

Picasso’s avant-garde experimentation was not confined to his paintings. It infiltrated the material features of his work: sheet music woven through cityscapes, ephemeral postcards reworked into painterly relief collage. These materials became a site for vision and perception to fracture, for the unconscious to surface, for consumer culture to be both critiqued and incorporated. Upcycled art for a new world.

Material Matters:

- Wallpaper masquerading as marble

- Newspaper clippings folded into space

- Gouache and charcoal pinned into false depth

In The Bottle of Vieux Marc (1913), there’s no clear subject. Just slivers of commercial print, a flattened table, and illusions splintered like language under pressure. It’s not a still life. It’s a ransom note for painting’s future. Fragmentation, hybridity, dreamscape, nostalgia.

Core Disruptions:

- Collage as an anti-illusionistic tool

- Merging “low” culture with “high” art

- Upending perspective, space, and hierarchy

Picasso and Braque didn’t romanticize the cut. They were tacticians. Their Cubist collages sliced open Western pictorial conventions and filled the wound with modern craft—bricolage, splicing, sampling, fusing—raw, organic, ephemeral. It was collaborative making at the edge of chance operations.

Legacy and Fallout:

- Influenced Dada collage, Surrealist collage, Abstract Expressionism, and Pop

- Laid groundwork for artists like Hockney, Rauschenberg, and Kippenberger

- Redefined painting as a site of construction, not illusion

These collages weren’t made to be beautiful. They were designed to be difficult. Misbehaving at the edge of abstraction. They poked holes in the picture plane and refused to patch them. They stared down the gallery and said: we’re not here to perform clarity.

Picasso didn’t stay long in the collage space. He was too restless, too prolific, but the rupture remained. He had cracked the aura of the singular image, the singular medium, the singular truth.

Art, once sacred, now had the stink of print shops and glue pots. In that stink—a bricolage aesthetic, subversive, painterly, ephemeral, layered—Picasso built a new language of protest, social change, and modern mythology. A collage that refused to be beautiful, but insisted on being seen.

Reading List

- pablopicasso.org

- The Bottle of Vieux Marc at the Met

- Guitar and Wine Glass at the Met

- Still Life with Chair Caning

- Still Life with Chair Caning on Khan Academy

- Pablo Picasso on Wikipedia

- Pablo Picasso Revolutionized Art Through Collage

- Picasso's Impact on the Art World

- Picasso's Influence on American Artists

11

Georges Braque

Georges Braque, Fruit Dish and Glass, 1912. Charcoal, wallpaper, gouache, paper, paperboard.

...

The Quiet Collagist Who Dismantled the Frame

If Pablo Picasso was the thunderclap, Georges Braque was the tremor beneath your feet. An avant-garde icon, co-founder of Cubism, and collage pioneer whose quiet radicalism redefined the 20th-century art landscape.

He didn’t court spectacle. He composed it in silence—deconstructing space with a draftsman’s restraint and a poet’s sleight of hand. In 1912, alongside Picasso, Braque co-invented papier collé—pasted paper collage. A cut-and-paste technique using found object art, vintage paper, and upcycled materials that reimagined painting as fragmented construction. He transformed the image into a bricolage of material and metaphor, with repurposed materials and layered surfaces disrupting illusions that had reigned since the Renaissance.

The French artist, modernist master, and early modernist, Braque’s Cubist collage work from 1912 onward—especially his Synthetic Cubism period—cemented his place as a founder of modern collage. Fruit Dish and Glass (1912), for example, is not a picture of a fruit dish. It’s the idea of one: a Cubist collage—fragmented, layered, and recontextualized—where found imagery and magazine collage become a conversation about the city’s refuse and art’s resurrection. The faux-wood wallpaper slices across the image like a conceptual joke, a cultural provocateur’s nod to the absurdity of bourgeois illusions.

In these works, Braque’s collage practice was a form of anti-art and subversive art—transforming urban life’s cast-offs into visual poetry and political protest. His practice of cutting, tearing, layering, glueing, and integrating was both chance operations and formal discipline—hand-made processes that pushed art into a modern mythology of transformation and resistance.

Key Materials and Techniques:

-

Charcoal and gouache layered with vintage paper, magazine clippings, newspapers, found imagery, and cardboard

-

Relief collage textures created by layering transparency overlays and hand-cut collage shapes

-

Geometric cut-outs, text-and-image fusion, and painterly brushstrokes to construct, deconstruct, and recontextualize surfaces

-

The found object as both medium and metaphor: advertisements, wrapping paper, ephemeral printed scraps—repurposed materials as new form

-

Playful image juxtaposition, collage-as-assemblage, and improvisation: every fragment layered, every cut a protest against illusionistic depth

-

The quiet patchwork of personal mythology, cultural mashup, and memory—a raw but polished interplay of harmonious and discordant textures

Theoretical Interventions:

-

Collage as a critique of illusionistic space—Braque’s mixed media collage made the surface itself speak

-

Subversive art and political collage through found materials and commercial ephemera—urban culture as source, street culture reimagined as high art

-

Intersectional dialogues of popular culture and avant-garde experimentation, with synthetic Cubism’s layered, painterly approach to chance operations and grid arrangement

-

Identity fractured into geometric abstraction; hybridity reimagined as layered surfaces; temporality and the unconscious captured in every pasted scrap

Braque’s Legacy and Lasting Impact:

A founder of Cubist collage and synthetic Cubism, Braque taught generations that fragmentation can be form, that surface is not passive, and that the cut-and-paste technique is itself a language of political critique and cultural mashup

His quiet but seismic interventions inspired future collage artists—from Schwitters and Rauschenberg to contemporary digital collage makers who echo Braque’s layering of images and ideas

Braque’s understated humor and wit in juxtaposing newspaper collage, painted collage, and torn paper art challenged painting’s narrative and created a new visual storytelling: poetic, ephemeral, and painterly in its graphic manipulation

His collages were not grand gestures but quiet detonations—raw yet sophisticated, ephemeral yet durable, a site of social commentary and personal narrative.

Braque didn’t want to shock. He wanted to reimagine how we see. In his collages, fragmented form became vision and perception itself—a Cubist collage that never healed but kept expanding. His legacy is a quiet yet powerful testament to the ephemeral and the eternal, to bricolage as both rupture and restoration.

He taught us that in the gap between cut and paste, between the found and the chosen, lies the possibility of seeing the world anew.

Reading List

- George Braques on The Art Story

- George Braque on Wikipedia

- George Braque's still lifes

- George Braque and the Cubist still life

- George Braque's Bottle of Rum

- Fruit Dish and Glass on Wikipedia

- How Braque became one of the greats

- Paint like George Braque

Conclusion

Collage isn’t potential—it’s pressure. The pressure to salvage, to rupture, to rebuild. It’s the artform born not of abundance but of aftermath. These eleven artists didn’t just redefine aesthetics. They built entire dialects from cultural wreckage, gluing new narratives where certainty had collapsed. Each used collage as a scalpel, as a protest sign, as a love letter, as a battlefield. They didn't decorate the world. They reassembled it from the detritus it tried to hide.

Whether layering found objects, repurposing propaganda, or slicing through domestic stereotypes, these collage artists carved meaning from contradiction. The materials are mundane—wallpaper, magazines, sugar wrappers—but the meanings are tectonic. They weaponized beauty. They exposed myth. They rendered society’s shiny lies as clutter cut into truth.

These were not just artists. They were codebreakers.

Their methods—improvisation, disruption, assemblage—mapped entire histories of resistance, migration, gender, race, and identity. And their legacy? It’s alive. You see it every time an image glitches on your feed, every time a billboard is remixed into protest, every time scissors hit paper and truth slips from the edges.

Collage is not nostalgia. It’s now. A radical form still splicing the world open—and daring us to look closer.

—

For Lazy Nerds & Visual Learners

Famous Collage Artists on YouTube