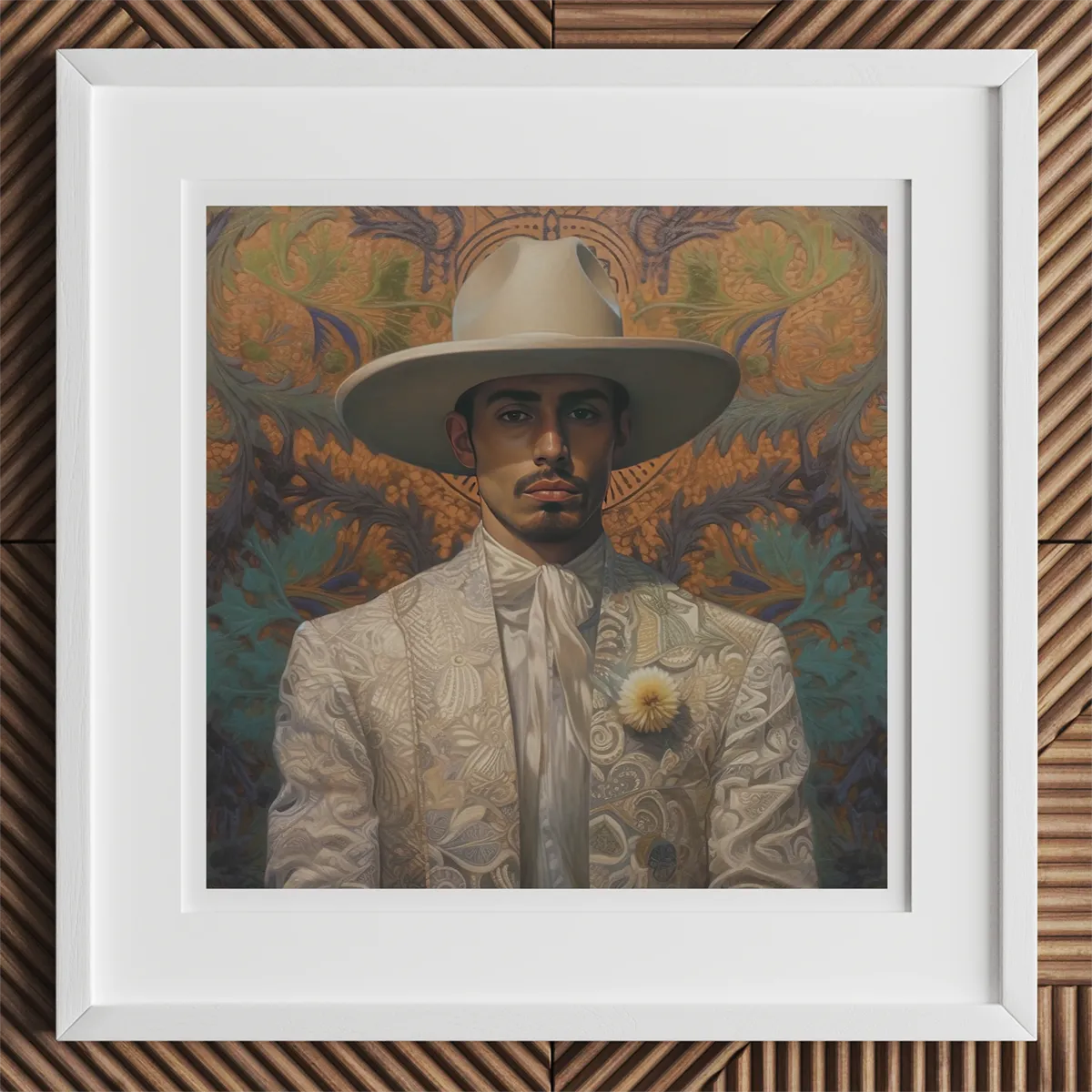

A lone figure carves his silhouette against the bleeding seam of twilight—boots dust-caked, hat slung low to parry the coming night. The cowboy: America’s sculpted ideal of grit, of stoic resolve whittled down to its calloused core. Yet myth drifts like dust. And if you ride far enough beyond the picked fences of legend, you find a frontier thrumming with stranger truths.

Beneath the polished spurs and sun-split leather, queer pioneers threaded their dreams across open plains, weaving identities no Victorian parlor could confess. In the wild west of judgment’s reach, they built lives in spite of the frontier’s savagery and because of its refusal to look too closely. They fled the cramped houses back East and rode into spaces vast enough to reimagine themselves, as feral and free as the horses they broke.

To live on the frontier was to stage a perpetual jailbreak from expectation. But stories of these LGBTQ+ settlers—their stolen kisses, their renegade households, their soft rebellions stitched into saddle bags—were left to desiccate in abandoned bunkhouses, scrubbed from the marble-faced mythologies America later built.

Yet now the ground stirs. Historians, scavengers of lost rhythms, gather fragments. Court records scrawled in fragile ink, anonymous ballads ash-fading at the edges, blurred photographs of men leaning too tenderly toward each other in canvas tents. These finds reveal a West that was wild not only in landscape but in love. A canvas of identities spattered brighter and queerer than Hollywood dared imagine.

This was a frontier more raw, more alive, and infinitely more subversive than any quick-draw morality tale could capture. Beneath the open skies, cowboys crossed cattle trails and boundaries of gender and intimacy—sometimes hidden, sometimes half-lit by firelight, always more complicated than the hero myths allowed.

Here, we’ll ride into that untamed territory: to the salt-bitter songs of cowboys who mourned their "lost pardners," to the resilience of transgender settlers who stitched new selves from frontier cloth, to the quiet ways two men could fold into each other's shadows without drawing a sheriff’s bullet or a preacher’s scorn. We’ll find the places where secrecy wasn’t shame—it was survival. And where survival meant daring to desire against the grain of empire.

The Queer West wasn’t a sidebar. It was a heartbeat, thudding steady beneath the hoofs of manifest destiny. Now it returns, guns blazing, to demand a reckoning.

Key Takeaways

- Beneath the rugged myth of the lone cowboy lies a hidden trail of queer love and gender-defying bravery, illuminated by letters, limericks, and campfire confessions—an untold frontier romance finally breaking free.

- The American West, mythologized as straight, white, and narrow, was in truth a kaleidoscope of queer identities, bachelor marriages, and transgender trailblazers who found fleeting freedom beneath endless skies.

- From cowboy poets mourning their "lost pardners" to transgender outlaws defying Victorian constraints, the frontier was always wild—unfenced by Eastern morals, vibrant with passion, secrecy, and subversion.

- Mythmakers may have straightened history, but buried beneath Hollywood’s veneer is an authentic West rich with queer intimacy, racial diversity, and gender fluidity—real stories riding boldly into view.

- Reclaiming the queer cowboy isn’t just rediscovering history; it’s a powerful, defiant assertion of existence, reshaping the American icon into a symbol of inclusivity, resilience, and unapologetic pride.

Gay Cowboys On YouTube

Historical Context: Unspoken Norms of the Wild West

Historical Context: Unspoken Norms of the Wild West

If the East was all corseted parlors and lace-gloved laws, the West was a skeletal draft—a rough, wide manuscript where rules barely scratched the surface of survival. By the late 19th century, the American frontier had become a scatterplot of mining encampments, dust-choked tent towns, and lonesome cattle ranches stitched thin across vast, ambivalent landscapes. Here, doctrine lost its fangs. Institutions, like rail lines and marriage licenses, came late if they came at all.

A historian once called it "a world saturated with masculinity"—and rightly so. The West’s economy ran on the muscle and mud-streaked bodies of men: loggers muscling old-growth forests into splinters, miners coughing blood in tunnels, cattle drovers whittling nights into card games and wary glances across the campfire. Gender norms arrived trailing sermons and court orders but found little traction where drought, dust storms, and snakebite dictated the terms of existence.

Out here, survival trumped surveillance. You needed a man to patch your broken ribs after a bronco stomped you flat, not to inquire about your sleeping arrangements. You needed a hand steady enough to stitch a wound or boil bad water into drinkable life—not a priest parsing your sins. Rigid moral hierarchies cracked like old leather beneath the greater urgencies of thirst, hunger, and the thin thread of breath held between one day and the next.

The farther you roamed from the territorial capitals and their parlor-watchful matriarchs, the looser the knots of Victorian propriety became. In these ad hoc communities, intimacy could flourish in the open spaces between necessity and discretion. A kind of frontier pragmatism emerged: if it kept the cattle moving and the wagons intact, affection—or something more complicated—between two men could pass without official comment.

The West wasn’t a utopia; it was a pressure valve. Every long day's ride away from Boston or Charleston loosened the corset strings of conformity another inch.

Homosocial vs. Homosexual

In the dust-thick air of the 1800s, there was no neat taxonomy of desire. No brightly lettered flags of "straight" or "gay" pinned to shirtfronts. Instead, the culture carved out a broad, rugged terrain of homosocial intimacy—men bunked together under the stars, leaned on each other’s shoulders as the coyotes howled, shared jokes and secret griefs without the wet worry of definitions clinging to them.

Cowboys slept side-by-side under wool blankets slick with trail dust, swapping murmured stories and passing canteens between cracked lips. Bonds formed, thick as saddle leather, strengthened not in confession but in the ache of endurance. What we now might name queer love sometimes glowed there—wordless, assumed, buried deep beneath ritual and labor.

In this loose braid of survival and camaraderie, the border between friendship and romantic attachment could blur, or vanish entirely. No court scribbled verdicts against it, so long as the herds were kept safe, the campfires lit, and no one grew loud enough to spark open scandal. It was a world too busy to inventory desires unless those desires disrupted the flow of cattle or cash.

The great gift of the frontier was its distraction: a thousand dangers more pressing than policing the shape of a man's affections.

“Strange Way of Life”: Tough, Resilient, Dependent but Roaming ‘Free’

From the flat ochres of the Kansas range to the cold pinpricks of Montana stars, the cowboy's life was stitched from both brutality and interdependence. He moved like smoke across valleys and gorges, his world stripped to essentials: a horse, a rifle, a skillet, a lonesome grin.

In this stripped-down existence, loyalty became currency. Men formed tight platoons of need—trusted each other to watch for rustlers, to yank a man from a river before the current made off with him, to stand steady when a snakebite fever came twisting through the tent walls. Partnership was not sentiment; it was architecture. The structures of survival often resembled the skeleton of intimacy.

In towns that flickered into existence between silver strikes and cattle drives, the rituals of shared survival were mistaken, sometimes willfully, for rugged fraternity. Jokes crusted with salt; songs thudded low and longing against campfire smoke. If two cowboys needed to share a bedroll, who would bother to inventory their dreams? Practicality shrugged at propriety’s trembling hands.

Freedom in the West was a paradox—liberated from one kind of structure only to be entangled in another made of cold nights and the warm necessity of another body’s proximity.

Isolation and Companionship

To live in the West was to tango with loneliness, a ragged waltz that threatened to saw a man’s mind apart. Isolation pressed down heavier than a ten-gallon hat soaked in rain. In the spaces between mountain ridges and desert flats, companionship was not a luxury—it was oxygen.

The "all-male family" was not a literary flourish but a bone-deep reality. In bunkhouses and on endless cattle drives, men formed de facto households: splitting chores, pooling meager wages, building something like a quiet domesticity out of beans, bacon grease, and late-night laughter.

Affection, when it slipped into view, often wore the plain face of necessity. No license, no church blessing, no kin gathering in stiff Sunday suits—only two men braced against winter, against loneliness, against the slow attrition of the heart.

No one asked too many questions, not when survival hinged on trust tighter than rope around a steer’s ankles.

Threats and Secrecy

But the West’s breathing room was never boundless. As railroads stitched the frontier into the body of the nation, and Protestant clerics pressed their hymnals against rough-bearded men’s chests, the old spaces of tolerance narrowed.

Starting in 1848, towns, particularly those blooming along the rails, began passing ordinances criminalizing "cross-dressing"—a legal assault aimed at pinning gender to the crossbeams of Victorian panic. Lawmen and vigilantes found new reasons to leer and judge, and for those who lived across forbidden lines of gender or love, mobility became salvation.

Cowboys and settlers who strayed from the prescribed scripts learned the delicate arts of discretion: shifting names, altering towns, blending laughter with caution. Trust was precious—and precarious. A loose tongue or an unfriendly sheriff could scatter a life faster than prairie fire.

If the frontier once allowed queer intimacy to slip through its wide, ragged seams, those seams now strained under the stitches of "civilization."

The great gamble remained: live truly and risk all, or survive in a half-shadow.

Reading Between the Ranches: Glimpses of a Queer Frontier

The West never wrote its queer stories neatly into the ledgers. Instead, they flicker at the margins: stray diary lines, bawdy campfire rhymes, half-blurred recollections leaning against the fence posts of memory. Stealth wasn't optional — it was survival’s second skin. Yet if you know where to look, the scattered breadcrumbs cohere into a rough, radiant trail.

Explicit documentation remains scarce — the wide sky favored silence over confession — but historians like Clifford Westermeier have sifted the dust for remnants. He unearthed a bawdy cowboy limerick where two men, sharing more than just kindling, became the butt and brilliance of the joke. Humor, in these cases, wasn’t mockery; it was the frontier’s camouflage — acknowledgment cloaked in jest, allowing desire to slip by unpunished so long as it didn’t shout.

In Gold Rush–era California, men outnumbered women so dramatically that intimacy and partnership between men found fertile, if unofficial, ground. A “pard” wasn’t just a pal — he might be a lifeline. Social events adapted without apology: when frontier dances unfolded, half the cowboys donned dresses stitched from curtains or old petticoats, stepping into the roles of absent women. Practical? Certainly. Playful? Often. But beneath the makeshift ribbons and laughter, deeper currents swirled. Some of those waltzing pairs spun the night into something neither camp jest nor mere necessity — something that slid, quiet and quicksilver, into real romance.

The frontier made scant room for judgment when survival stood as the higher court. Partnerships, flirtations, and affections bloomed in spaces too rugged for prying eyes — written not in manifestos, but in the subtle touch of a hand while crossing a river, or a nickname whispered across the firepit.

Little Hard Evidence, Plenty to Ponder

The documentary record remains porous, but what seeps through invites careful reckoning.

Cowboy limericks survived — laced with crude wit and longing barely disguised. Diaries crumbled into dust but captured glimpses: notes about a “pard” tending a feverish partner with a tenderness rarely extended even to kin. In the faded margins of these logs, affection thrums — not as anomaly, but as heartbeat.

Contemporary observers sometimes left clues, if not open admissions. In 1890s Denver, a professor recorded that the city’s homosexual subculture spanned many professions — ministers, teachers, even judges — and that "the usual percentage of homosexuals" could be found among university students. His observation wasn’t couched in scandal or outrage — just weary acceptance, as if noting the migration of birds.

Meanwhile, in 1911 San Francisco, an anonymous gay man penned a testament equal parts caution and awe. Life, he wrote, could be "hard but extremely interesting" — a rare, flickering self-portrait of queerness at the edge of a continent still pretending it didn’t exist.

Historians may fret over the scarcity of proof, but the frontier’s living record lay less in official archives and more in the rituals of endurance: the twin coffee mugs hung side-by-side; the shared tobacco pouches; the saddle scars rubbed into twin leather seats. Every absence from the record was itself an encoded survival.

Bachelor Marriages and Same-Sex Unions

Among the sagging porch beams and sod huts of the West, bachelor marriages stitched themselves into the everyday warp and weft of survival. These weren’t ceremonies robed in taffeta or sanctioned by church bells; they were pacts of labor, intimacy, and shelter hammered out under the iron thumb of necessity.

Two men would settle together — splitting chores, pooling earnings, nursing each other through fever and broken ribs. Communities, pragmatic to the bone, often turned a blind eye or offered quiet acceptance. As long as these partnerships kept the cattle fed, the wood chopped, and the taxes paid, sentiment mattered little to frontier eyes.

The language of partnership was often public: “my man” or “my pardner.” Displays of affection that would have wrinkled noses back East passed largely without comment if they didn’t disrupt the economy of sweat and survival.

Yet sometimes, the veil slipped — and trouble followed.

-

In 19th-century Montana, two bachelors lived together for years, until death broke the pair apart. The survivor’s raw, widow-like mourning so unsettled the townspeople that they whispered and recoiled, unsure where camaraderie ended and something "unnatural" began.

-

In New Mexico Territory in 1873, a U.S. Army post trader faced formal charges for engaging in a "most unnatural" relationship — the vague phrasing a legal cudgel when specific language was still taboo.

-

In 1896 Texas, a man named Marcelo Alviar faced a sodomy charge. His bond was set equal to that of a murderer — a stark reminder that while quiet same-sex partnerships often slipped under the radar, exposure could turn deadly in an instant.

Bachelor marriages reveal a frontier elasticity about intimacy — tolerance, until the quiet breach became too loud, too visible for Victorian comfort.

Love and Ambiguity: Cowboy Poetry and Song

If historians must lean on poetry to fill the silences of the West, they are in fine company.

Cowboy poetry flourished in the late 1800s — rough riders turning wordsmith by firelight, their verses stitched with longing, loneliness, and bonds far deeper than bunkhouse banter. Among these voices, Charles Badger Clark Jr. stands out like a scar traced lovingly by time.

In 1895, Clark published "The Lost Pardner," a poem steeped in grief so dense you can almost smell the dust of a freshly filled grave. He wrote not of battle honor or rough camaraderie, but of a loss that hollows the world: the mornings drained of color, the rides shorn of joy. His "pardner" isn’t merely a colleague — he is the axis around which the cowboy’s soul turned.

Clark’s work appeared without scandal. Readers, trained to gloss queer undercurrents into the safe pasture of "brotherhood," perhaps missed—or chose not to see—the fierce personal ache blazing beneath the stanzas.

Whether intended or not, "The Lost Pardner" now stands as a quiet, blistering anthem of queer grief on the range. In the cracks between its lines, we glimpse the shape of a love too wild to name and too real to be erased.

Beyond Cowboys – Saloons, Sailors, and the City

The Queer West galloped far beyond the dusty silhouette of the cowboy and the cattle trail’s churned dirt. It seeped into every isolated pocket of male labor: the logging camps that cleaved ancient trees from the Sierra Nevada; the railroad crews that hammered iron veins into the continent’s spine; the sailing ships that stitched coastal towns into commerce; the army outposts pitched in barren landscapes where law and longing alike twisted on the wind. Wherever men gathered beyond the reach of towns and Victorian vigilance, a rough intimacy unfurled — practical first, but seeded with something more subversive and tender.

Bachelor bonds bloomed across these outposts of hard work and harder survival. In remote lumber camps, bunkhouses crowded with men pulsed with homosocial energy: shared meals, shared jokes, shared bunks. On the rolling decks of ships, sailors packed together cheek-to-jowl, finding fleeting tenderness between voyages. Soldiers, cradled by tents and danger, formed loyalties too deep for army records to admit.

No formal language named what passed between these men; necessity had no patience for categories like “straight” or “gay.” Yet proximity braided itself into affection, and affection — often unspoken, often unwitnessed — fed the hearts that the land, the sea, and the grind of labor tried daily to hollow.

The patterns repeated, again and again. Where women were absent, intimacy between men stitched itself into the seams of daily life, sometimes unnoticed, sometimes quietly blessed by a pragmatism that cared little about the shape of desire so long as the work was done.

In California’s Gold Rush camps, with women scarce as rainfall, it became customary for men to pair off not only for economic survival but for social balance. At frontier dances, when the fiddler struck up a reel, half the men donned dresses spun hastily from spare cloth, stepping into feminine roles so the music could be honored and the night could sing. Sometimes it was play. Sometimes it was something else, glimmering in the torchlight: a fluttering, a beginning, a risk.

As the century tipped toward urbanization, queer life followed, riding the new iron rails into the rising cities of the West. By the 1890s, Denver, San Francisco, and Seattle all sheltered burgeoning queer subcultures, clandestine but vibrant. A professor in Denver noted with offhand precision that homosexual men could be found across the professional spectrum — ministers, judges, teachers, students — a mundane observation that spoke volumes about the breadth and quiet persistence of queer life even under the moralistic gaze of Victorian expansionism.

In these frontier cities, a parallel society quickened in boarding houses, alleyway saloons, and boarding-school whispers. Men who had lived as pards on the cattle trails or bunkmates in the mining camps found echoes of those old intimacies in new taverns and rented rooms. Though newspapers often cloaked these existences in euphemism or lurid scandal, the truth shimmered beneath: the Queer West had not faded with the cattle drives; it adapted, flowering through the cities like wild columbine through abandoned wagon tracks.

Later, the sex researcher Alfred Kinsey would uncover an unexpected reverberation of these frontier patterns. In his 1948 study, Kinsey found that some of the highest rates of homosexual intimacy occurred not in bustling metropolises, but in rural farming communities — descendants, perhaps, of those early frontier attitudes where scarcity, isolation, and survival blurred the lines that cities would later demand be drawn in ink.

The Queer West's legacy stretched beyond cowboys and cattle trails into the Great Depression’s farmhands and the rail-hopping drifters of the Dust Bowl. Everywhere that hard labor pushed men together and forced them to rely on each other more than on distant laws or absent churches, the old ways flickered back into life: partnerships forged from necessity but nourished by something warmer, quieter, and infinitely harder to erase.

In truth, the frontier’s rough gospel of survival had always carved space—hidden, mutable, tenacious—for queer lives to endure. Not through the blessing of tolerance, but through the shrugging pragmatism of a world too busy surviving to enforce distant morals with any real vigilance.

Even when the cities rose and the churches built higher steeples, even when the courts issued stricter laws and the dime novels straightened every cowboy’s back into rigid heterosexuality, the truth rode on: whispered in boarding houses, etched in bunkhouse walls, stitched into the bodies of men who had once danced in borrowed skirts beneath the open stars.

Queer Pioneers and Outlaw Tales from the Old West

To truly humanize this history, let’s meet some of the notable figures – individuals whose stories, though fragmentary, give us windows into the Queer West. These range from poets and lawmen to outlaws and aristocrats, painting a picture as diverse as the West itself.

The Cowboy Poet and His “Lost Pardner”

Among the quietest, sharpest echoes of the Queer West rides Charles Badger Clark Jr., the cowboy poet of the Black Hills whose verses stitched longing directly into the trail-dust and prairie grass. In 1895, Clark composed "The Lost Pardner," a mourning hymn for a beloved companion who had died, leaving behind not just an empty saddle but a world unmoored.

Clark's poem vibrates with a grief too saturated to be dismissed as simple camaraderie: the aching absence of shared mornings, the hollow rides across once-familiar valleys, the sky itself seeming to darken under loss. Although Clark never publicly named the nature of his bond, "The Lost Pardner" thrums with a love deeper than platonic loyalty — an intimacy wrapped in Western stoicism but burning through its folds.

In Clark's time, such affection could be brushed off by polite readers as mere brotherhood. Yet today, the pulse beneath his words is clear: grief shaped by deep personal devotion, the kind frontier life rarely permitted to surface in daylight but that still sang itself, trembling and defiant, into poetry.

Sir William Drummond Stewart’s Wild Adventures

Long before the West was paved into myth, a scandalized Scottish aristocrat fled Victorian whispers to find freedom in the wild heart of America. Sir William Drummond Stewart, arriving around 1833, traded the rigid expectations of Britain for the fur-trading camps of the Rocky Mountains — spaces alive with fluidity, commerce, and rough carnival.

At the grand annual rendezvous, where trappers, Native Americans, and traders bartered, brawled, and danced, Stewart found not only adventure but companionship in Antoine Clement, a French-Cree hunter whose presence in Stewart’s journals and later commissioned paintings quietly defies historical erasure.

Their bond bloomed unhidden among men who lived by different codes, and in 1843, Stewart staged a spectacular medieval-themed masquerade on the shores of Fremont Lake, Wyoming: knights in armor, jesters, feasts that blended European fantasy with frontier grit. To modern eyes, this flamboyant pageant reads as rich with queer flair — a playful, defiant reclamation of identity far from England’s censure.

Though later years saw Stewart retreat into more conventional life, the memory of his time with Clement — and the paintings capturing their connection — remain stubborn artifacts of a Queer West that understood freedom differently, with camp, with courage, with an arm loosely slung across a partner’s shoulders.

Outlaw of Love: “Two-Gun Lil” and the Bisexual Bandit

Beyond poets and aristocrats, the West made room — or at least begrudgingly allowed space — for outlaws whose transgressions crossed both legal and social lines.

Among them lingers the figure of Bill Miner, the “Gray Fox,” a stagecoach and train robber whose legendary exploits included whispers of same-sex liaisons. A Pinkerton detective circular described him bluntly as a sodomist — language weaponized to scandalize, but also an unintended testament to the deeper currents of queer life the law sought to criminalize and control.

Alongside men like Miner, myth swirls around women such as “Two-Gun Lil,” a pistol-packing rebel often described wearing men's attire, revolvers slung from her hips, her romantic entanglements rumored to shrug at the dictates of gender and propriety. Though historical details blur into folklore, their presence testifies that gender non-conformity and fluid sexuality rattled the mythic skeletons of the frontier even before Hollywood stiffened them into archetypes.

These outlaw figures remind us: the Wild West was never truly tamed, not by railroads, nor by sheriffs, nor by the strictures of Victorian decency. Queerness galloped alongside every stagecoach, ducked behind every saloon door — part of the frontier’s lawlessness not just in act, but in existence.

Gender Non-Conformists of the Frontier: Trans Cowboys and Cross-Dressing Outlaws

The Wild West also served as a stage for those who dared to live as another gender. Sometimes it was for survival or economic opportunity, sometimes for love – often a mix of all three.

Charley Parkhurst

Among the most legendary figures riding these contradictions was Charley Parkhurst, born in 1812 and assigned female at birth. Disguising his origins beneath calloused hands and a weather-beaten hat, Parkhurst carved out a life many cisgender men could only envy: as one of the finest stagecoach drivers in California, commanding teams across treacherous mountain passes where bandits and broken axles lurked with equal menace.

Parkhurst lived and worked as a man for decades, earning a reputation for daring that few questioned. In 1868, he even cast a vote in a U.S. presidential election — a radical act, given that women would not officially gain that right nationwide for another half-century. It was only upon Parkhurst's death that neighbors discovered the anatomy he had hidden from public view, a revelation that left more questions than answers but did not diminish the respect he had earned.

Historians now argue that Parkhurst should be recognized as a transgender man by contemporary standards — a pioneer not just of the frontier’s rough roads but of gender self-definition itself, long before language caught up to lives already being lived.

Sammy Williams

If Parkhurst rode the dusty arteries of commerce, Sammy Williams labored in the sweat and sawdust of Montana’s lumber camps. For two decades, Williams passed as a male lumberjack, swinging axes alongside crews who accepted him without public question or qualm.

When Williams died — sometime near age eighty — the truth of his assigned sex at birth emerged, but by then it scarcely seemed to matter. To the men who had worked shoulder to shoulder with him, Williams was — and had been — "one of the guys." In the brutal pragmatism of frontier survival, identity often bent to skill, endurance, and the ability to pull your weight when the frostbitten timber cracked under the saw.

Williams’s life stands as a quiet but profound testimony to how the frontier’s necessity could carve space for lives that Eastern parlors and pulpits would have condemned outright.

Harry Allen

More defiant, and more hounded by authorities, was Harry Allen — born Nell Pickerell in 1882, but living defiantly as a man across the Pacific Northwest’s rough-edged cities.

Allen wrangled broncos, tended bar, swaggered through saloons, and refused women's attire long before modern categories like "transgender" provided even a sliver of social defense.

Seattle and Spokane newspapers chronicled Allen’s life with lurid fascination, reporting frequent arrests — not for cross-dressing per se, since Seattle lacked a statute explicitly forbidding it — but under catch-all charges like vagrancy or disorderly conduct. His repeated collisions with the law reveal less about his so-called "criminality" than about society’s mounting panic as the West hardened its moral codes to mirror the East.

Despite harassment, Allen persisted — a bronco-riding, whiskey-swilling challenge to the narrow boxes the 20th century tried to nail shut around gender. His existence, messy and magnetic, shatters any illusion that transgender lives are a recent phenomenon: Allen lived, loved, fought, and faltered on the same muddy streets as the loggers, cowboys, and barkeeps who shared his world.

Myth of the Straight, White Cowboy & Erasure of the True Wild West

If queer cowboys and non-white cowboys were so common, why do popular images still default to the straight, white Marlboro Man? The answer lies in how the West was later mythologized—in dime novels, Wild West shows, and especially Hollywood. 20th-century storytellers deliberately created a mythic cowboy archetype to serve American ideals, excluding inconvenient truths about diversity.

The “Lone” Cowboy

The cowboy, that brooding silhouette cut against the blood-orange sunset, did not emerge from the open plains whole-cloth. He was sculpted — painstakingly, deliberately — by mythmakers who wanted him to carry not just saddlebags but ideologies.

In the dime novels of the late 19th century and the celluloid reels of early Hollywood, the cowboy became a "lone" figure: grim, isolated, a self-reliant sentinel riding across an unpeopled wilderness. He needed no companions, no entanglements. His heart, like his six-shooter, pointed straight and unerring.

But this vision was a polished lie, a fantasy tailored to nourish emerging American ideals of rugged individualism. In truth, the frontier cowboy lived cheek-to-jowl with his peers — swapping jokes, supplies, warmth, and sometimes tenderness. Real cowboys moved in crews, bunked together in cramped quarters, and formed bonds of necessity so profound they often blurred into affection.

The myth scrubbed these realities clean, wary that close male partnerships might suggest something less tidy than the narrative demanded. Emotional interdependence, vital on the trail, became invisible in fiction. Where two cowboys once shared a bedroll against the cold, Hollywood left one riding alone into an antiseptic sunset.

Whitewashing the Range

Hand-in-hand with this erasure of emotional complexity came a ruthless bleaching of racial truth.

The cowboy was recast in films and novels as an Anglo-Saxon hero taming a wild, empty land — never mind that the land was neither empty nor tame. The actual West teemed with Indigenous nations, Mexican vaqueros, Chinese railroad workers, and African American freedmen carving lives from harsh soil.

Historical records reveal that one in four cowboys was Black — a statistic that staggers against the alabaster tide of cinematic cowboys played by actors like John Wayne. Countless more were Mexican or Indigenous, inheritors of centuries-old traditions of horse mastery, cattle herding, and land stewardship that predated the American frontier myth altogether.

This deliberate whitewashing sanitized conquest, turning genocide and cultural theft into a pageant of white grit. It erased not only the diverse realities of those who built the West but also buried the fluid, unruly intimacies that thrived among them.

Where the real frontier was brown and black and wild with unexpected kinships, the myth forged a clean, white, heterosexual figure — a moral mascot for Manifest Destiny.

African-American Cowboys

In the scorched aftermath of the Civil War, many newly freed African Americans looked westward, seeking the kind of freedom Reconstruction too often denied. They found it, sometimes, in the saddle.

Figures like Nat “Deadwood Dick” Love rose to near-mythic stature, his autobiography detailing a life spent wrangling cattle, busting broncos, and surviving gunfights not as a novelty but as a peer among peers. On the frontier, Love often found that skill outshone skin color — at least until towns grew large enough for Jim Crow’s iron hands to catch up.

Another titan was Bill Pickett, a Black cowboy who pioneered the rodeo sport of bulldogging — the act of wrestling steers to the ground by biting their lips, a technique he developed from observing cattle dogs at work. His fame eventually earned him a place as the first African American inducted into the National Rodeo Hall of Fame.

Yet for all their contributions, men like Love and Pickett were erased from the collective imagination, their saddles left empty in the history books. Hollywood’s Westerns did not ride with them. Textbooks rode past them. Only now do their stories reemerge, kicking down the corral fences of myth.

Indigenous Cowboys: The Two-Spirit Horsemen

If Black cowboys were pushed from the frame, Indigenous cowboys were rendered almost invisible — or else villainized.

Yet Native Americans, particularly Plains tribes like the Comanche, had long been expert horsemen before the frontier’s mythology had even drawn its first breath. As cattle ranching expanded westward, many Indigenous men became indispensable as scouts, herders, and wranglers.

Within these communities, traditions also existed that honored gender fluidity — identities we might now recognize as Two-Spirit. In cultures from the Lakota to the Navajo, individuals who blended masculine and feminine roles were often granted unique spiritual and social positions. Some Two-Spirit people lived openly among their tribes, embodying multiple roles across gendered divisions that colonial societies sought to harden.

This Indigenous flexibility around gender and sexuality likely influenced the broader ethos of the early frontier: a tacit tolerance born from practical need and older cosmologies that respected variance.

But with settler expansion came violent suppression. Two-Spirit traditions were targeted for erasure alongside language, ceremony, and land. What had once flourished in harmony with the earth was hunted to the margins, rendered nearly invisible by the twin engines of church and state.

Yet the tracks remain — if you know where to ride, if you listen closely to the old songs.

Beyond Brokeback: Reclaiming the Cowboy in Modern Times

Beyond Brokeback: Reclaiming the Cowboy in Modern Times

In 2005, Brokeback Mountain tore a hole in the mythic fabric of the West and let the forgotten ghosts howl back through. Annie Proulx’s short story — and its wrenching cinematic adaptation by Ang Lee — dared to stitch two men into the rugged tapestry of cowboy life not as a punchline or tragic afterthought, but as the aching, beating heart of the frontier’s most sacred archetype.

The love story of Jack Twist and Ennis Del Mar, slow-blooming and devastating, unsettled audiences because it struck too close to the myths America had learned to cradle like a worn Bible. The cowboy, that untouchable icon of stoic masculinity, was shown with his heart laid bare — bruised, yearning, and profoundly queer.

Some critics raged, as if sacred ground had been defiled. Yet the film’s resonance only underscored what the myth had worked so hard to bury: that the West was never the hermetically sealed, heterosexual stage show it was sold as. Brokeback did not invent queerness in cowboy culture; it pulled aside the curtain to reveal what had been thundering quietly underneath for centuries — the secret histories written in folded letters, stolen glances, and abandoned ranch houses.

The International Gay Rodeo Association: A New Frontier

Long before Brokeback Mountain flickered across movie screens, queer cowboys were already wrangling their own traditions back into daylight.

By the 1970s, a grassroots movement coalesced around rodeo events where LGBTQ riders could buck bulls, barrel race, and lasso goats free from the stiff judgment of traditional circuits. The first major event, the National Reno Gay Rodeo, galloped into life — raising funds for charity and creating sanctuary at a time when AIDS was ravaging the community and mainstream acceptance remained a distant mirage.

In 1985, various regional rodeos united under the International Gay Rodeo Association (IGRA), formalizing a network that still rides strong today. Unlike traditional rodeos with rigid gender divisions, IGRA events were — and are — gleefully subversive. Men and women compete across categories, drag performers sashay through the arena, and events like "goat dressing" blend humor with athletic prowess.

Under the dust and spectacle lies something deeper: a reclamation of Western identity, an insistence that the cowboy’s courage was never contingent on who he loved or how she dressed. The gay rodeo stakes a stubborn, joyous claim to a heritage too often weaponized against its own children.

Cowboys as Icons in LGBTQ Culture

The cowboy — once scrubbed of tenderness, color, and complexity — has become an unlikely phoenix in queer iconography.

In the 1970s and '80s, the cowboy’s broad shoulders and denim swagger were reappropriated into a symbol of queer bravado. The Village People danced it onto disco floors; Tom of Finland inked it into erotic mythos, his cowboys towering with exaggerated masculinity, mustaches glinting like sabers.

The aesthetic wasn’t merely camp. It was a subversion — a re-forging of the cowboy mythos into something that held pride rather than exclusion. Rough, rural manhood, once wielded as a cudgel against queerness, was remade as armor, as celebration, as seduction.

And it wasn’t limited to men. Lesbian ranchers, drag kings, and transgender rodeo stars found fertile ground in the cowboy myth too — drawing not only on its visual power but on its deeper spirit: resilience, reinvention, defiance of constraint. They became inheritors of a tradition much older than Hollywood’s narrow scripts, kin to the frontier women who shouldered rifles and rode horses in men’s boots long before permission was granted.

A More Inclusive Western Mythos

Today, the Western mythos is being not merely critiqued but rebuilt — plank by plank, song by song, frame by frame.

Academics, filmmakers, and artists are unearthing the layered, messy truths of frontier life and refusing to return them to shallow graves.

-

Films like The Power of the Dog explore the poisoned legacies of closeted life under the wide skies.

-

Documentaries and photo exhibitions spotlight queer rodeo athletes, tracing the modern echoes of those old hidden partnerships.

-

Novelists weave queer Western romances that refuse tragedy as the only ending.

This is not invention; it is restoration. A bringing-to-light of what was always there, obscured by the self-serving myths of empire and morality. The cowboy is no longer confined to whiteness, maleness, heterosexuality. He — or she, or they — now rides with the full complexity, pain, grit, and beauty that the true frontier always demanded.

For rural queer youth, the revised Western saga becomes a mirror where none existed before — a way to see themselves not as exiles from their communities but as part of an ancient, stubborn lineage of those who lived fiercely under open skies.

This is the frontier reimagined not as a sanitized origin myth but as a living, breathing archive — one whose stories are still being written in dust and blood and starlight.

Riding Proud into the Sunset

The Queer West is no mirage, no retroactive invention etched wistfully onto the landscape. It is history — sun-seared and bloodstained — humming underfoot like the low vibration of distant thunder. And to ride into its truths is not merely to correct the ledger of the past, but to resurrect entire lives once buried under the sand-drifted myths of rugged, solitary men.

At one level, this reclamation is about archival justice: combing through brittle court records, yellowed diaries, and offhand newspaper references to find the traces of gay cowboys, transgender ranchers, and queer outlaws who refused to conform even when conformity came armored with violence. Their existence demands that we unlearn the Hollywood lies — that we recognize the cowboy not as a singular straight white titan but as a tangled braid of identities, hopes, and loves.

But it is also more than scholarship. It is an act of spiritual continuity.

Figures like Charles Badger Clark, singing grief for a lost pardner into the cold prairie wind; Sir William Drummond Stewart, staging medieval masques of love and liberty along Fremont Lake; Harry Allen, swaggering in defiance across saloon thresholds — these individuals didn’t just survive the frontier. They reshaped it from within, daring to live lives unshackled by the narrow prescriptions of gender and sexuality.

Their breath is still in the dust.

Today, to claim the cowboy — queer, trans, Black, brown, Indigenous, defiant — is an act of defiance wrapped in patriotism. It says: We were here, building your towns, roping your steers, riding your storm-tossed landscapes long before you wrote us out of your storybooks.

It says: The frontier was never a straight line. It was always a crossroads.

As scholarship deepens, as films and exhibitions widen the horizon, the cowboy is no longer the monolith of Western exceptionalism. He is, at last, a multitude — riding proud beneath skies as plural and unpredictable as the human heart itself.

Each time a gay rodeo rider hoists a trophy, a trans rancher rebuilds a fence-line, or a poet spins old Western rhythms into new songs of resilience, another plank is laid in the bridge back to truth. The frontier never belonged to one kind of soul. It was — and remains — a wild, untamable testament to all the ways human beings insist on becoming themselves against every gate and every gun.

To see the Queer West fully is to understand that it never needed permission to exist.

It only needed someone — someone like us — to look back across the dust and say:

You were always here.

You were always riding with us.

And we are still riding, together, into the fire-lit dusk.

Reading List

Berger, Knute. Meet Nell Pickerell, Transgender At-Risk Youth of Yesteryear

Benemann, William. Men in Eden: William Drummond Stewart and Same-Sex Desire in the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade

Billington, Monroe Lee, and Roger D. Hardaway, eds. African Americans on the Western Frontier

Black Hills Visitor Magazine. Biography: Charles Badger Clark

Boag, Peter. Redressing ‘Cross-Dressers’ and Removing ‘Berdache'

Brown, Benjamin. Black Cowboys Played Major Role in Shaping the American West

Capozzi, Nicco. The Myth of the American Cowboy

Clark, Badger. Sun and Saddle Leather

Collins, Jan MacKell. Untold Tales of Gender-Nonconforming Men and Women of the Wild West

Cooper, James Fenimore. The Leatherstocking Tales

Durham, Philip, and Everett L. Jones. The Negro Cowboys

Garceau, Dee. “Nomads, Bunkies, Cross-Dressers, and Family Men: Cowboy Identity and the Gendering of Ranch Work.” — Across the Great Divide: Cultures of Manhood in the American West

Hardaway, Roger D. African American Cowboys on the Western Frontier

Hobsbawm, Eric. “The Myth of the Cowboy

Jessie Y. Sundstrom. Badger Clark, Cowboy Poet with Universal Appeal

The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. Deadwood Dick and the Black Cowboys

Kinsey, Alfred C. Sexual Behavior in the Human Male

Lawrence, D. H. Studies in Classic American Literature

Miller, Hana Klempnauer. Out West: The Queer Sexuality of the American Cowboy and His Cultural Significance

Osborne, Russell. Journal of a Trapper; In the Rocky Mountains Between 1834 and 1843

Packard, Chris. Queer Cowboys: And Other Erotic Male Friendships in Nineteenth-Century American Literature

Patterson, Eric. On Brokeback Mountain: Meditations about Masculinity, Fear, and Love in the Story and the Film

Remington, Frederic. Late 19th-century cowboy articles; see Hobsbawm, “Myth of the Cowboy.”

Roosevelt, Theodore. Ranch Life and the Hunting-Trail

Slotkin, Richard. Myth and the Production of History. - Ideology and Classic American Literature

Turner, Frederick Jackson. The Frontier in American History

Vestal, Stanley. Jim Bridger; Mountain Man