Was Leonardo da Vinci ADHD? Probably...

Five centuries ago, the left-handed Florentine stood with brush aloft, mind already sprinting toward his next flash of astonishment. Was it an unbuilt flying machine? A Virgin on his panel? The clay horse beside him? Or that dissected heart he sketched after breakfast? All of them waiting. Half-done. Begging for attention and... signals of neurodivergence?

Historians call it genius; neuroscientists suspect a mind wired for hover and leap, restlessness and rapture. So what happens, exactly, when curiosity burns faster than calendars? When perfection wrestles attention?

Half a millennium on, neuroscientists and art historians comb da Vinci's ricochets for clues: was Leonardo’s turbulence the Renaissance variant of what we call Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)? Or could the erratic orbit of his creativity map onto a wider constellation of neurodivergence?

This voyage tunnels through notebooks, autopsies, royal contracts, and 20 minute catnaps to decode the electricity powering the Renaissance's brightest comet. Following the spiral of his unfinished wonders to discover why the gaps between masterpieces may matter as much as the work itself. And how his cognitive weather still changes the climate of creativity today.

You may never trust the myth of linear brilliance again…

Key Takeaways

Discover why Leonardo’s trail of half-forged projects reveals neurodiverse rhythms, not negligence or laziness.

Learn the cognitive science of mind-wandering and hyperfocus that underpins many of his cross-disciplinary leaps.

Tune into practical methods—from polyphasic sleep to notebook scaffolding—that modern innovators still adapt today.

See how stroke, melancholy, and perfectionism intertwined with a prodigious creative engine in his final years.

Rethink “genius” as a partnership between divergent cognition and supportive structures rather than polished completeness alone.

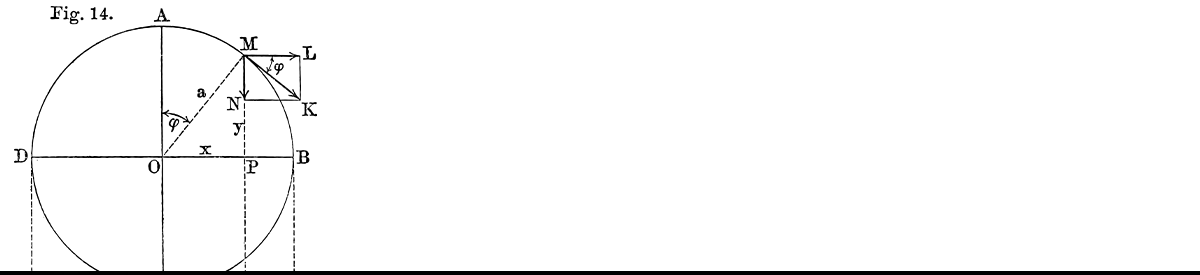

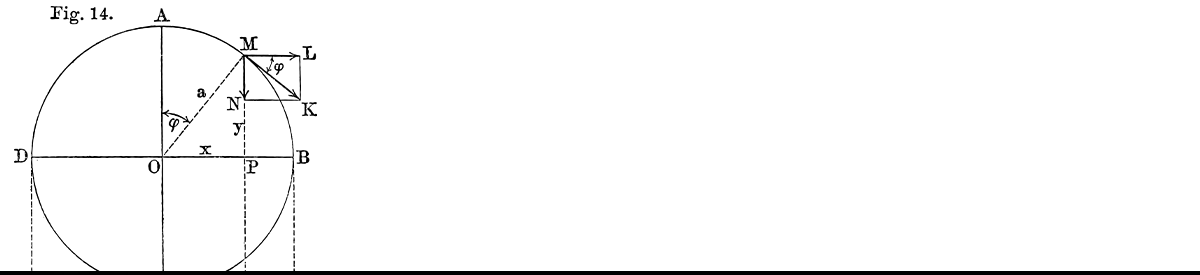

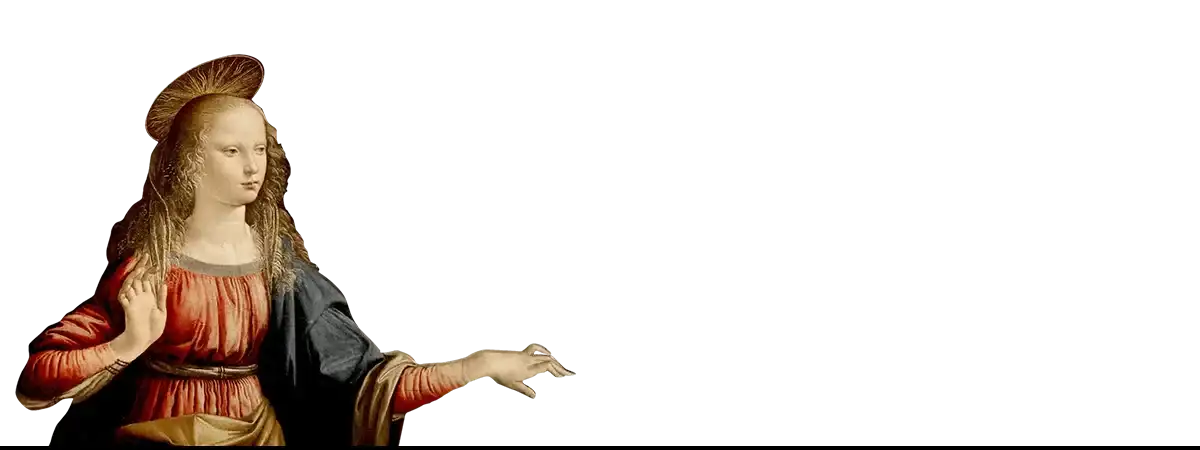

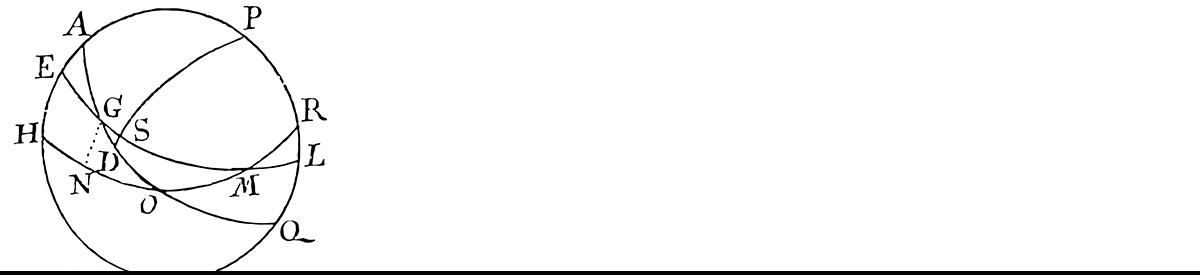

Leonardo da Vinci, Adoration of the Magi (ca. 1481–1482)

A Brilliant Mind, Unfinished

Leonardo da Vinci’s career reads like a celestial chart filled with radiant bodies and sizzling comets.

And yet, there are fewer than 20 completed paintings attributed to da Vinci. Whether that's because he completed so few is a an open question. Another delicious mystery about the man who left behind mountains of sketches, half-finished canvases, and grand projects unrealized.

Even in his own time, da Vinci's inability to finish work was proverbial amongst the patron class of merchants, bankers and nobility. Historian Giorgio Vasari, who mostly praised the master's prodigious skill, sums up the sentiment with his own cutting remark:

"He would have made great proficiency in learning... if he had not been so variable and unstable; for he set himself to learn many things, and then, after having begun them, abandoned them."

The DailyArt Magazine puts it more kindly:

"Leonardo likely hesitated to declare his work complete. The more he learned… the more he felt the urge to improve."

Unbeknownst to Vasari or Leonardo, da Vinci's unfinished work would open countless doors of perception. For millions of scientists, artists and innovators benefiting from his treasure trove these past 500 years. Across centuries and to this very day.

So whether you think da Vinci's neurodivergent or not, his insatiable curiosity is the gift that keeps on giving. And his other ADHD traits are hard to unsee if you take time to look.

Timeline — Messy Masterpieces

| Project | Outcome |

|---|---|

| 1478: Adoration of the Shepherds altarpiece | Never completed – reassigned after non-delivery |

| 1481–1482: Adoration of the Magi | Abandoned on departure to Milan |

| 1489–1499: Gran Cavallo | Unrealized – clay model destroyed |

| 1495–1498: The Last Supper | Finished but delayed; experimental technique deteriorated quickly |

| 1503–1506: Battle of Anghiari | Left unfinished; painted over later |

| 1503–1519: Mona Lisa | Held back -Leonardo thought it was incomplete |

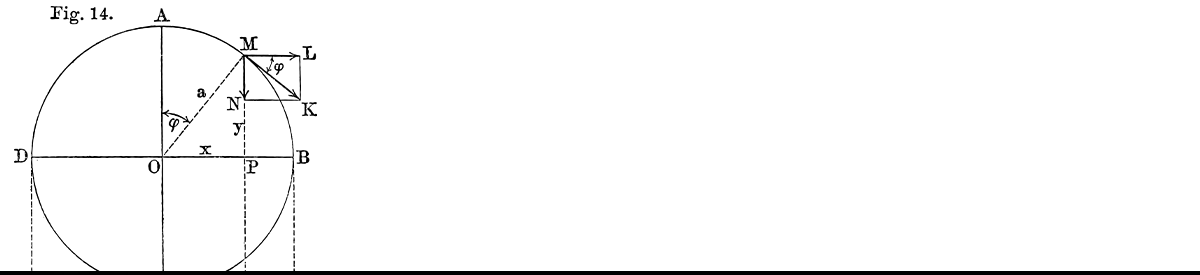

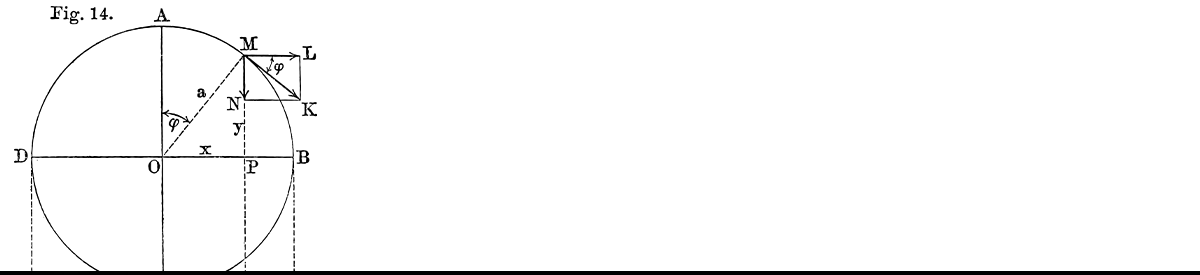

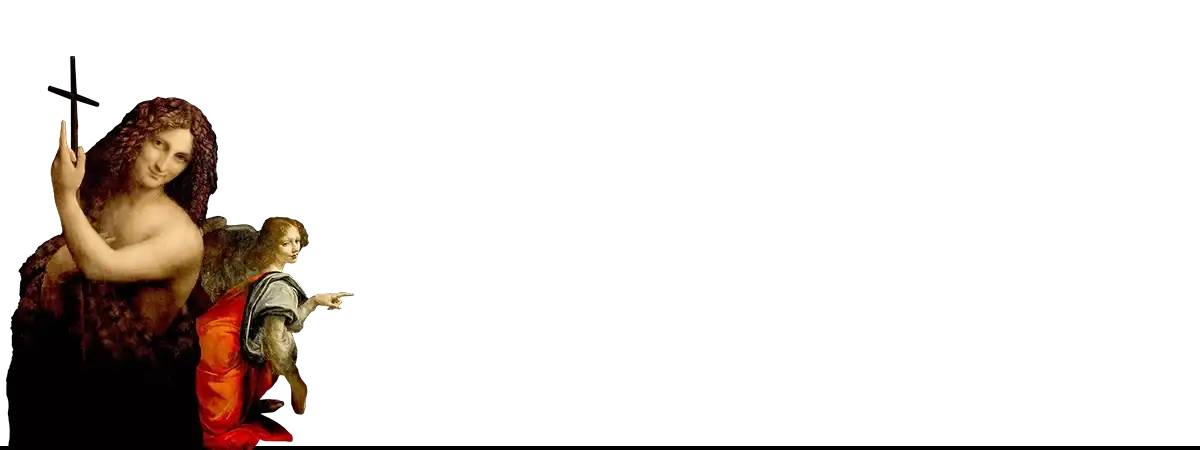

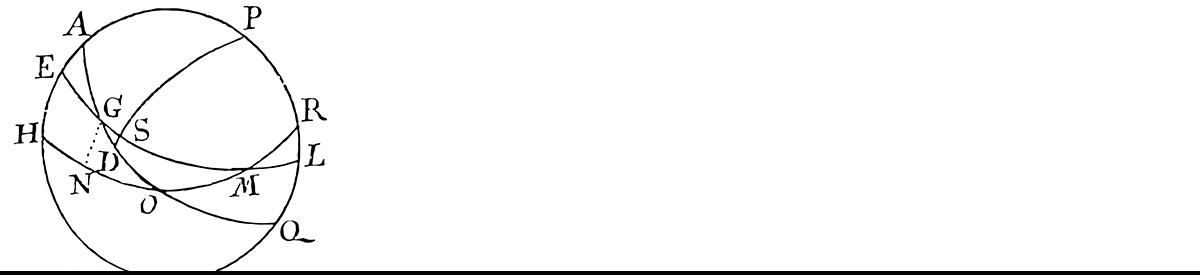

| 1506–1508: La Scapigliata | Unfinished oil study |

| 1510–1515: Anatomy treatise | Unpublished in his lifetime |

| 1513–1516: Trivulzio Horse | Abandoned early stage |

| 1519: Treatise on Painting | Compiled notes, finalized posthumously |

Tales of a Distracted Genius

In 1478 da Vinci accepted a commission to create an altarpiece for Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio. He pocketed the advance then never delivered. By 1482 he relocated to Milan, drafting a flamboyant proposal for anything and everything Duke Ludovico Sforza desired. His now-famous letter promising war machines, hydraulic marvels, and “secure positions from which the artillery might dominate.” A 15-point pitch deck for the Florentine military industrial complex... but sexy.

Within this grand ambition, scholars detect the neural signature of what modern business calls “serial ideation.” And dazzled, the Duke hired him. But... any executive will recognise the risk of onboarding a visionary whose calendar obeys muse over milestones. And history records more of Leonardo's sketches than completions.

Take his Gran Cavallo, an ambitious plan for a colossal bronze horse that consumed twelve years of intermittent labor. And after all that time with nothing but a five-meter clay model—an idea of an idea—the Duke still marveled at it. He also grew impatient.

A contemporary noted Ludovico sought another artist for the job because he “doubted Leonardo’s capability to bring it to completion”. Then fate intervened and Leonardo got a get out of jail free card through political strife followed by an invasion. French troops stormed Milan in 1499 and the clay model was shattered—da Vinci's Gran Cavallo abandoned, yes, but also by necessity... in the end. Long story short: a monumental dream trampled in the theater of war.

The Gran Cavallo was just one project, though. Leonardo abandoned plenty of others. And sure, many artists did at the time, of course. In a world of art as tradesmanship, sort of, creating mockups for wealthy patrons was part of the job. Still is. Except Leonardo and Michelangelo couldn't send a pitch dick round to their dream clients. Their mockups would often be part of a lengthy interview process across days spent in royal courts. With your (possible) new benefactor walking in at any moment to see what you're up to. And if they didn't like it? You'd do it again, if you were lucky. Make it this way or that. Or... they'd kick you out and find new talent.

Has much changed for artists in this day and age? Not really. Everything's pretty much the same but there's much more happening a helluva lot faster.

So yes, sure, Leonardo the polymath tradesman would've been sketching and practicing hist craft all day long. But if we're just looking at numbers, Michelangelo gifted us with 192 paintings. Leonardo left 20 that we know of. And a spectrum of innovative visions, of course. All crafted with precision, mostly in his notebooks. Still, we can't escape the fact Leonardo was so distractible even triumph carried the scent of risk.

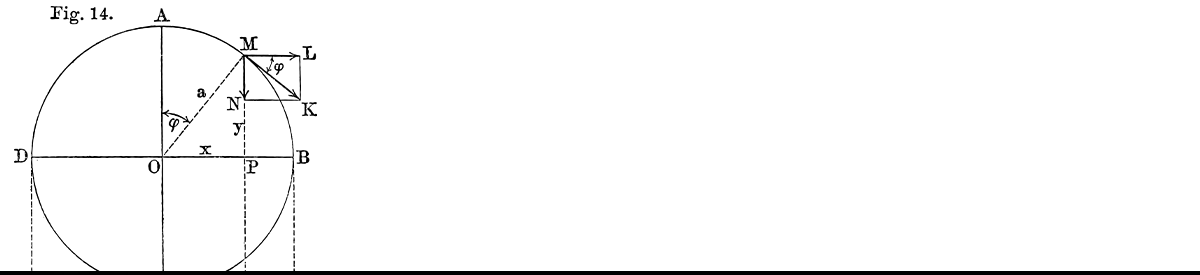

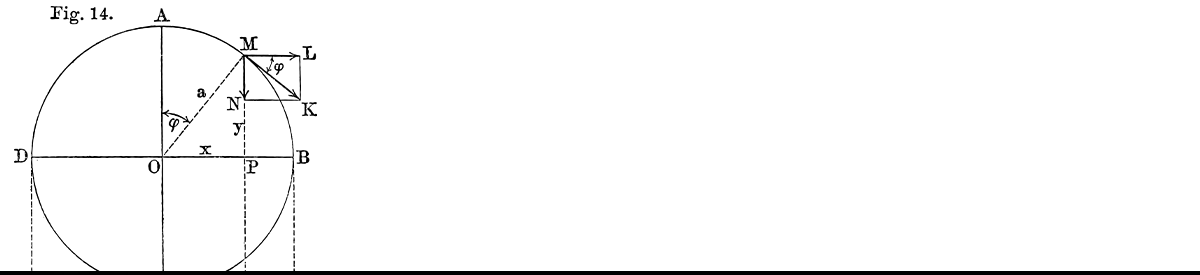

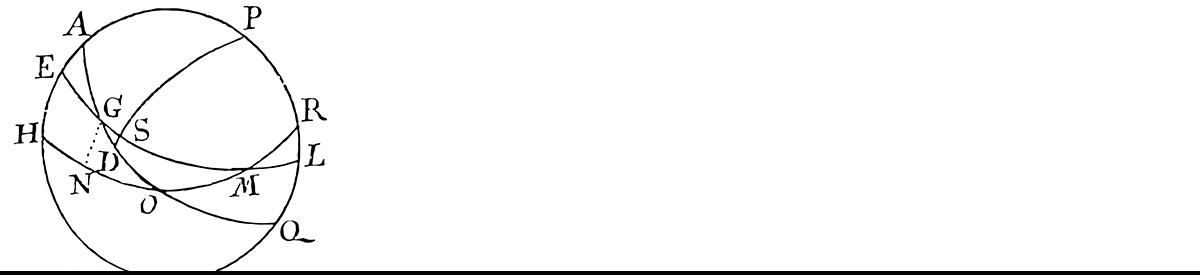

While laboring on The Last Supper (1495–1498), da Vinci's workflow swung between trance-like marathons and mystifying pauses. Employed to decorate the whole refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Leonardo famously dragged out the mural’s completion over several years. And as for his workflow, we have snippets that tell us a lot.

Matteo Bandello, a novelist in the Duke’s court, observed days when the master “would not lift a brush”—hours spent gazing, absorbing, recalculating. Other days he would paint from dawn till dusk “without putting the brush down”.

Exasperated by the inconsistency, Duke Ludovico drafted a contract mandating completion within a fixed span—rare coercion for a court artist, evidence of chronic anxiety trying to corral the sparks of genius.

It was an anxiety Leonardo himself admitted to. Writing in his own notebook that “None of my projects were ever completed for Ludovico.” This wasn't true, depending on who you ask. But if we're asking the artist himself, we have our answer. Or one of them, because this confession doesn't need to be looked back on through a lens of self-pity.

Reading it differently, it becomes an archaeological layer. Revealing executive friction beneath dazzling intellect. Leonardo cared that much about the work. And as we'll see later on, nothing was ever really good enough for Leonardo when it came to his own work. Perfectionism ran deep.

Looking back through a contemporary lens is a guessing game anyway. In many ways. But one gift we have in the here and now sheds light on way back when. These days, we know some characteristics seen as 'liabilities' in ADHD – a wandering mind, craving for stimulation – canbestow creative advantages if channeled constructively. Leonardo’s life seems like a case in point.

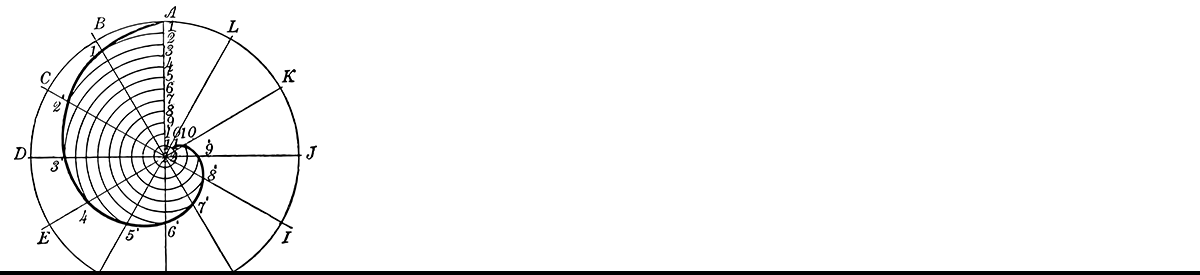

His tendency to jump between subjects meant he cross-pollinated ideas across disciplines in revolutionary ways. Take his anatomical studies of muscle and bone — informing the uncanny realism of his painted figures. Or his observations of water flow influencing designs for city infrastructure.

And we must also weigh the technological audacity of these undertakings. A five-meter bronze cast stretched the metallurgical limits of fifteenth-century Europe; an experimental oil-and-varnish mural on plaster outran chemistry by centuries. In that sense, Leonardo’s “failures” often represent history failing to keep pace with him.

One thing's for sure: Leonardo didn't silo his interests. Cross-pollination was the engine of his creativity.

Restless Rebel

Within this roll-call of first-rate but half-forged dreams we glimpse hallmarks modern clinicians associate with executive dysfunction and chronic procrastination. Both core facets of ADHD. Yet to frame the maestro solely through a diagnostic lens would flatten the kaleidoscopic physics of his mind. His perfectionism operated like gravity: holding each project in orbit until an even mightier curiosity pulled him elsewhere.

Still, the raw behavioral pattern—lava-bursts of innovation followed by cooling basalt—mirrors contemporary case files of high-IQ adults with ADHD who juggle multiple hyper-focused endeavors while everyday duties slip through temporal cracks.

We know Leonardo da Vinci was distracted. If distraction is measured by the number of tantalising loose ends, that is. But was Leonardo lazy? Hardly. His notebooks reveal 13-hour anatomical vigils, nocturnal dissections illuminated by guttering candles, and to-do lists longer than parchment rolls can hold: “measure Milan’s canals,” “draw the heart valves,” “calculate the weight of a swallow’s flight.” Such industrious mania aligns with the flip-side of ADHD—a capacity for hyperfocus when stimulus equals passion.

Underneath the whirl resides another force: restlessness. He slept little, sometimes adhering to a polyphasic pattern of cat-naps every four hours—a schedule today touted by bio-hackers but in the Quattrocento marked Leonardo as an odd, sleepless comet. Fact remains, restless bodies often house restless brains. Often noted in modern sleep-disorder literature about adults with attention-related conditions.

We should also note his left-handed mirror writing, occasional orthographic slips, and preference for images over text. These facets fuel speculation about co-occurring dyslexia, itself a common fellow-traveler with ADHD.

The sparks blazed across disciplines; the forest sometimes failed to kindle. For patrons dependent on timely delivery, those sparks could scorch. For posterity, they illuminate an unprecedented multidimensional notebook—arguably more valuable than any single polished painting.

Let's pause with a paradox: the very brain-states that prevented Leonardo completing work also fertilised his cross-domain breakthroughs. Muscle dynamics enriching portraiture, hydrodynamics informing town planning, optics refining chiaroscuro. To cut Leonardo's distractibility from his creative profile would mean amputating the provenance of his genius.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper (ca. 1495–1498)

The Unquiet Apprenticeship

Born in the village of Vinci, 1452, young Leonardo grew up with an innate freedom to wander. He was not sent to a formal Latin school, leaving him largely self-taught and self-directed. As a boy, he famously drew fantastical creatures and experimented with rudimentary inventions. Family accounts speak of an energetic, inquisitive child. Perhaps tellingly, a court record from when Leonardo was 24 describes an incident where he was charged with a youthful indiscretion (later dismissed) – an early hint of a restless, risk-taking spirit. A hallmark of ADHD's taste for audacity.

Leonardo’s formal training began under Andrea del Verrocchio, a leading Florentine artist. Verrocchio’s bottega smelled of ox-hide glue, molten bronze, adolescent sweat, and possibility. Into this crucible strode the seventeen-year-old Leonardo, illegitimate son of a notary and a peasant girl, eyes alight as though the sun itself had chosen fresh pupils.

Apprentices learned to hammer, grind, model, gild, and sing madrigals while mixing vermilion. And most absorbed technique like orderly scribes. Leonardo inhaled entire cosmologies. And all with a conversational agility mirroring present-day accounts of ADHD adults. Leveraging rapid associative thinking to connect disparate fields.

And so, the apprentice’s talent quickly shone. Often vanishing to sketch river eddies beneath Ponte Vecchio. Practicing lira da braccio at night. Claiming the resonant belly of cedar taught him proportions more elegantly than Euclid.

"Verrocchio’s workshop was the perfect playground for a budding polymath... early mentors observed his scattershot focus. Verrocchio noted that while Leonardo had ‘a wide breadth of interests and eclectic talent’ like himself, the young man ‘lacked… rapid execution and organizational skills’." — Giorgio Vasari

Still, his talent blazed. And when Verrocchio accepted a civic commission for The Baptism of Christ, Leonardo was tasked with painting an angel. Scribes record that Verrocchio handled most final varnish and client communication, shielding Leonardo’s wandering process from bureaucratic blowback. Still, Leonardo delivered such ethereal sfumato that his master, legend says, set down his brush forever. A triumph—but it also signalled the apprentice’s private paradox: incomparable contribution, minimal completion.

The rope always frayed under the tension of deadlines. Early patrons witnessed both miracle and migraine, too. A local wool-guild elder, after commissioning a polychrome banner, complained the boy delivered a study of drapery folds worth framing—yet no banner. Such incidents seeded Florence with rumours: Leonardo was ADHD avant la lettre.

And as Verrocchio’s atelier faded behind him, its echo—the clash of disciplines under one roof—seeded Leonardo’s lifelong method. Each later incompletion carries DNA from this apprenticeship: unabashed scope, relentless pivot, tolerance for provisional states.

Classroom without Walls

Unlike contemporaries steeped in scholastic Latin, Leonardo built his syllabus by scavenging: bird wings, botanical cross-sections, mechanic’s notes, Moorish treatises learned from travellers.

Leonardo’s autodidactic torrent reflects what modern educational psychologists call divergent learning pathways, common among gifted students who struggle with institutional pacing.

Records from da Vinci’s parish suggest he learned basic abacus faster than local clerks, but abandoned formal schooling early, preferring lived geometry. Tracking shadows across sundials or mapping crickets’ leaps.

From a neurodevelopmental standpoint, such bricolage learning corresponds to hyperfocus bursts: intense, self-rewarding engagement triggered by intrinsic curiosity. The same mechanism later enabled him to dissect thirty cadavers across two winters, documenting each tendon with monastic care while forgetting, say, to invoice patrons.

Risk, Impulse, and the Florentine Court

Court registers from 1476 contain a discreet notation: Leonardo and three companions were questioned over a licentious rumour then released for lack of evidence. While biographers debate its nature, psychiatry flags a pattern: risk-taking behaviour often shadows impulse-laden attention profiles.

No conviction followed, yet documents show Leonardo relocated his social orbit, perhaps recognising the thin ice beneath flamboyant non-conformity.

Soon after, he proposed to Lorenzo de’ Medici a mechanical lion capable of opening its chest to scatter lilies—an early proof-of-concept for kinetic sculpture but also for imaginative bravado.

Historians see youthful showmanship; clinicians glimpse dopamine-seeking flourish, typical of restless minds craving novelty.

Sleep, Scribbles, and Cognitive Design

Surviving notebook fragments from this period teem with mirrored admonitions: “Sketch storm movement”; “Observe lizard jaw.” Sentences halt mid-logic as drawings surge—to modern eyes a hypertext of cognition.

Coupled with polyphasic sleep notes (“wake at second bell; study moon halo”), the pages suggest circadian experimentation aligned with maximizing creative intervals. Contemporary sleep science links such self-hacked rhythms to attention-regulation attempts—an intuitive workaround centuries before clinicians coined the term.

Meanwhile, linguistic slips—a missed consonant here, a reversed syllable there—hint at dyslexic processing overlays. Combining left-handedness, atypical orthography, and spatial genius, neurologists infer right-hemisphere language dominance.

Atypical lateralisation often correlates with enhanced visuo-spatial rotation skills—pivotal for the anatomical cross-sections that would later stun London’s Royal Society.

Leonardo da Vinci, La Scapigliata (ca. 1506–1508)

A Mind That Wandered the Cosmos

By middle age, Leonardo da Vinci had fully embraced the life of a polymath – arguably to an extreme. In the first years of the 16th century, one finds him simultaneously engineering canals for the Florentine government, dissecting cadavers at the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, devising flying machines and armored vehicles, tutoring pupils in painting, sketching grotesque caricatures for amusement, and jotting down scholarly musings on geology and the flow of water. It is as if no single human endeavor could contain his curiosity.

And from the spring of 1500, the Florentine Republic reclaimed da Vinci like a prodigal comet. He returned from war-scarred Milan with trunks of loose folios, scraps of hydraulics, and a clay model’s broken ear in his baggage.

The city buzzed with new commissions, yet Leonardo’s journal opens that year not with patron lists but with an admonition to himself: “Describe the tongue of the woodpecker.” This single line encapsulates the next decade—the period scholars call his boundless middle orbit—when curiosity eclipsed chronology and the notebook became his true cathedral.

Still, even the most indulgent patrons frayed at the edges of Leonardo's distractibility. In 1503, the Republic of Florence hired Leonardo and rival Michelangelo to paint opposing military epics in the Palazzo Vecchio.

Michelangelo, 28 and Leonardo's greatest rival for patronage, produced a fierce vision in weeks. Leonardo chose an experimental oil-wax emulsion, laboured intermittently, then watched pigment slide off the wall when winter dampness rose.

Council minutes record the mounting frustrations: funds allocated, hall still bare. The episode illustrating a workplace tension still familiar in modern studios—visionary technique colliding with project-management entropy.

So it was that Leonardo had to contend with the practical consequences of his divergence. At times, it cost him financially and socially.

In his forties, he lost the Battle of Anghiari commission in Florence after it stalled – a publicly professional setback. In his fifties, Pope Leo X reportedly grew impatient with Leonardo’s experimentations in Rome, allegedly quipping “This man will never accomplish anything! He begins by thinking of the end before the beginning.”

Such critiques from powerful figures must have stung. We can imagine Leonardo late at night, surrounded by anatomical drawings and engineering schematics, asking himself why he pursued so much and finished so little. Did he feel isolated by his own brilliance? Did he long for a calmer mind?

One clue comes from Francesco Melzi, his devoted pupil who inherited Leonardo’s papers. Melzi wrote that Leonardo’s “spirit was never at rest.” Within that simple remark lies a world of psychological truth: Leonardo experienced life with an unceasing mental churn, a beautiful and daunting gift.

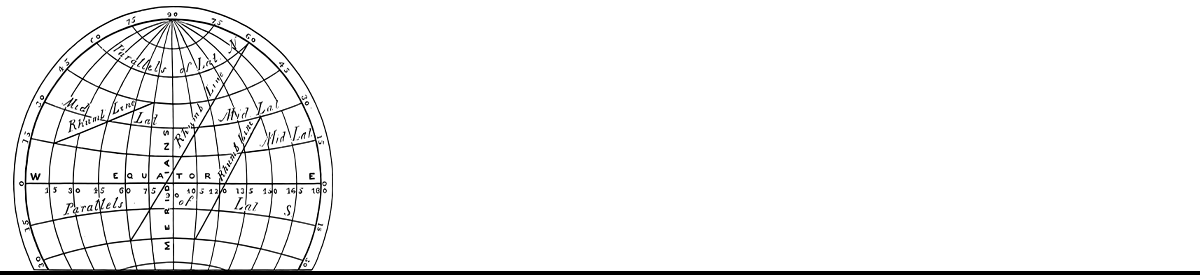

The Notebook Nebula

Paradoxically, Leonardo's distractibility never slowed him down. Quite the opposite. Between 1500 and 1513, da Vinci generated an estimated 6,000 manuscript pages filled with mirror-script observations: vein valves, river vortices, propeller sketches, laughter muscles.

Paging through the codices today feels like glancing at a galaxy-wide neural scan: clusters of mechanical diagrams adjacent to doodled infants; sermonettes on water erosion marginal to cross-sections of human lips.

Neuropsychologists point out that such non-linear clustering mirrors the associative leapfrog seen in adults managing attention-regulation differences. The pages refuse disciplined sequence; instead they spiral, each idea gravitationally bending the next.

Hyperfocus & Time Dilation

Modern clinicians differentiate distractibility from hyperfocus, a paradoxical tunnel-vision that locks onto intrinsically rewarding tasks.

Leonardo’s middle years teem with such episodes. Witness his anatomical campaign at Santa Maria Nuova hospital (1507–1510): he dissected more than thirty cadavers, sometimes working dusk to dawn while autumn fog curled outside the charnel house. In one stretch he spent eight consecutive nights tracing cerebral ventricles, pausing only for bread and ink.

Surgeons complained the artist commandeered their mortuary, yet his resulting drawings would centuries later prove anatomically prophetic. The same man who overlooked payroll receipts could render a coronary valve with millimetric fidelity—classic hyperfocus trade-off: granular mastery, administrative amnesia.

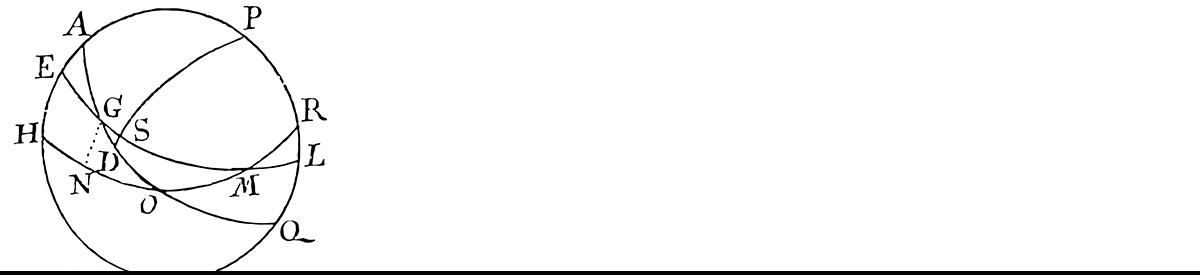

The Trait Matrix

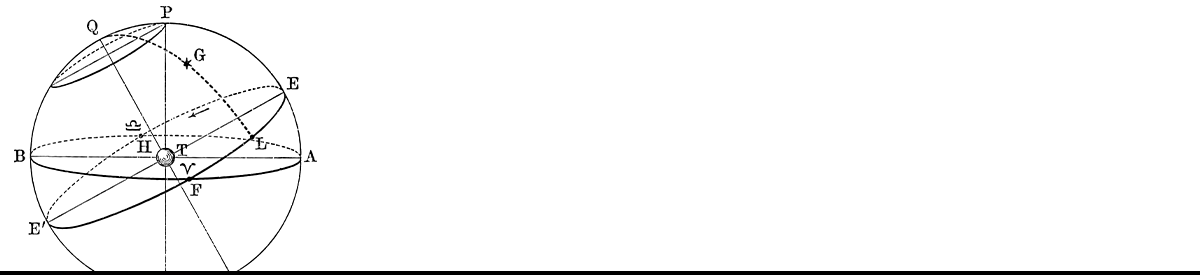

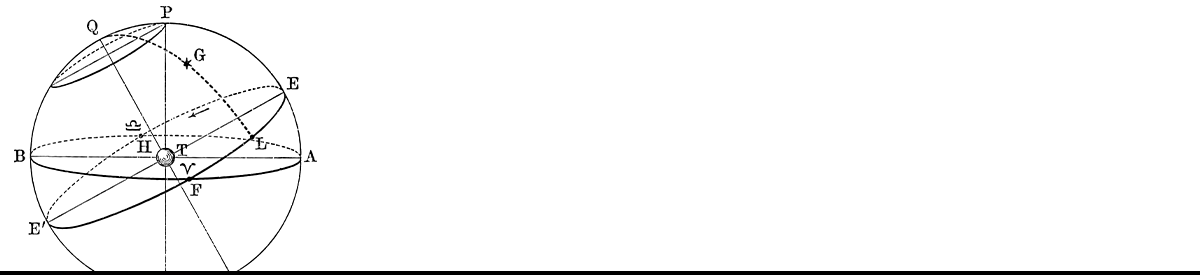

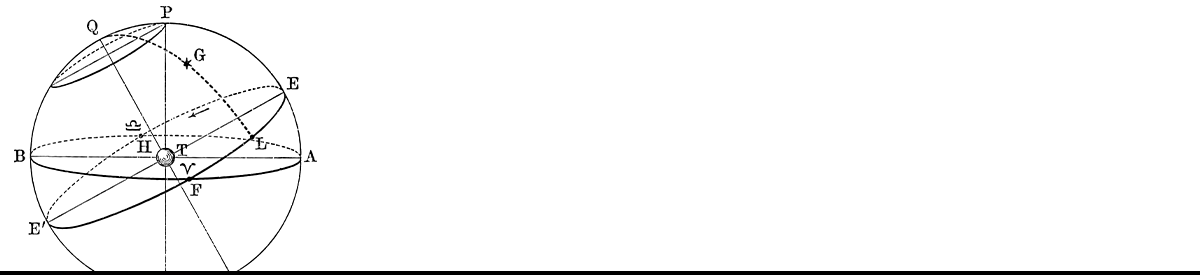

The table below underscores a cognitive rhythm of vault-and-spiral—vault toward fresh intrigue, spiral into depth, then vault again. Renaissance archives supply no diagnostic terminology, of course.

Dr. Marco Catani writes, “I am confident that ADHD is the most convincing and scientifically plausible hypothesis to explain Leonardo’s difficulty in finishing his works”. Importantly, ADHD does not imply a lack of intellect or creativity – it is independent of IQ. In Leonardo’s case, his extraordinary intelligence and visual thinking seems to have coexisted with (and been enhanced by) an ADHD-style brain.

Still, let's not to retroactively diagnose without caution. We rely on historical observations, which are inevitably incomplete. Yet the alignment between those observations and modern clinical criteria is striking. His behavioural mosaic aligning uncannily with present research on creative professionals displaying executive-function variability.

Consider this breakdown of ADHD-like traits and how Leonardo exemplified them:

| Diagnostic Feature | Leonardo’s Evidence |

|---|---|

| Sustained attention: Difficulty maintaining focus on lengthy tasks | Abandoned Borgia fortification survey to examine fossil shells |

| Task completion: Multiple projects left mid-stream | Sala del Gran Consiglio mural halted after experimental undercoat failed |

| Impulsivity: Rapid shifts to novel stimuli | Mid-dissection notes segue into bird-flight calculations within same folio |

| Hyperfocus: Intense, prolonged engagement in preferred interest | Eight-night marathon dissecting cerebral ventricles |

| Working memory: Misplaced or unfinished administrative matters | Duke of Györ’s payment reminders stapled (unopened) inside Codex Arundel |

Cosmological Thinking

Restlessness alone cannot explain Leonardo’s cross-domain syntheses; something else powered the interstellar jumps between hydrodynamics, musical consonance, and vascular turbulence.

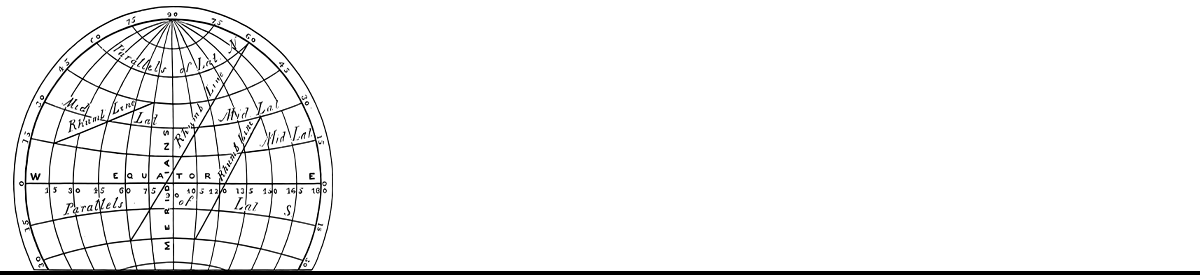

Historian P. Sandoval Rubio argues that Leonardo’s notebooks reveal a “macro-micro doctrine”—every water eddy a model for planetary weather, every heartbeat a clue to celestial mechanics.

Such cosmological mapping hints at a brain wired for pattern-seeking on a pan-scale, another cognitive signature frequently reported in individuals whose attentional spotlight skitters until it lands on structural parallels across fields.

In a 2019 review, Dr. Rubio notes that attempts to label Leonardo by today’s standards reveal our own “limitations” in understanding such a multifaceted genius. Emphasizing that Leonardo’s approach to knowledge was holistic and integrative – he “did not distinguish art from science”, treating all inquiry as connected.

This interconnected thinking is very much in line with neurodivergence — leaping between domains, defying linear categorization. While today’s medicine might compartmentalize traits into diagnoses, Leonardo lived in a time when an eccentric genius was accepted on his own terms.

Peripheral but Precise

A second hallmark of his middle orbit is the peripheral obsession—topics irrelevant to any commission yet catalogued with manic care.

The woodpecker tongue appears in six separate folios, each time more anatomically exact. Why? Ornithologists speculate the inquiry informed his shock-absorber sketches for siege rams, but no draft blueprint survives. Contemporary neurologists note that such magnetic micro-subjects often serve as dopamine anchors for minds coping with fluctuating executive control.

Similarly, Leonardo’s infamous shopping lists during this era mix groceries with grand design: “Buy eels, wax, and a live cricket; measure solar noon.” The miscellany seems whimsical until decoded as a behavioural coping strategy—scaffold mundane tasks beside high-interest curiosities to hijack motivation. A technique occupational therapists now teach adults managing attention-variability.

Sleep Architecture & Bio-Rhythms

Leonardo’s polyphasic schedule intensified in these years: he logged 20-minute naps every four hours and recommended the routine to disciples. Recent chronobiology suggests such segmentation can exaggerate attentional peaks and troughs -stimulating creative bursts yet impairing routine upkeep.

Letters from his assistant Francesco Melzi complain that master and pupils sometimes “forgot to eat” during those nocturnal laboratories. Maladaptive or transhuman? Perhaps both: the method kept Leonardo’s creative engines humming yet left a trail of neglected contracts.

Legacy of the Middle Orbit

Yet what sprang from this decade of scattershot intensity? The Codex Leicester’s lunar-tide theory, the first layered drawings of coronary circulation, aerial screw prototypes, and chiaroscuro refinements that would gestate the Mona Lisa. Remove the wandering and you erase the weave.

Cognitive-science literature now posits that certain executive-dysfunction profiles may underwrite “exploratory innovation”- breakthrough that arise not from linear progress but from high-variance search patterns.

Leonardo embodies the thesis: he searched erratically, and in the erratic search unearthed universal constants. His cosmos was a notebook; its constellations, interleaved sketches; its dark matter, the ideas he never had time to formalise.

As the second decade of the sixteenth century closed, Leonardo’s orbit would shift again to Rome, then the Loire Valley. But the cognitive engine described here remained constant: vault, spiral, vault.

Whether we badge his rhythm as ADHD, divergent executive wiring, or simply renaissance fervour, the notebooks prove one thing: brilliance sometimes rides shotgun with volatility, and the journey, though disordered, can redraw the heavens.

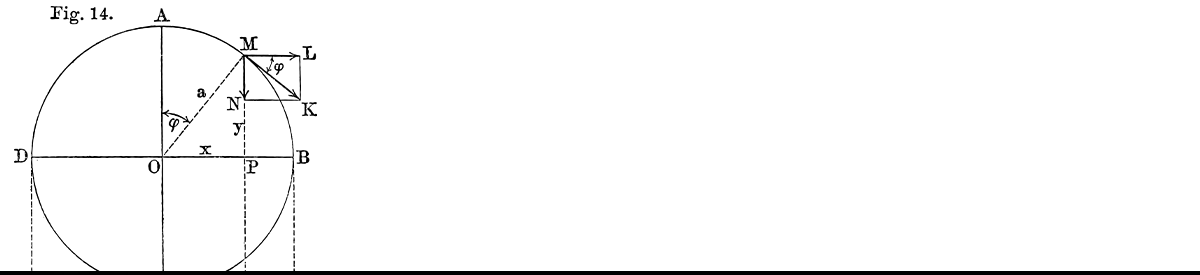

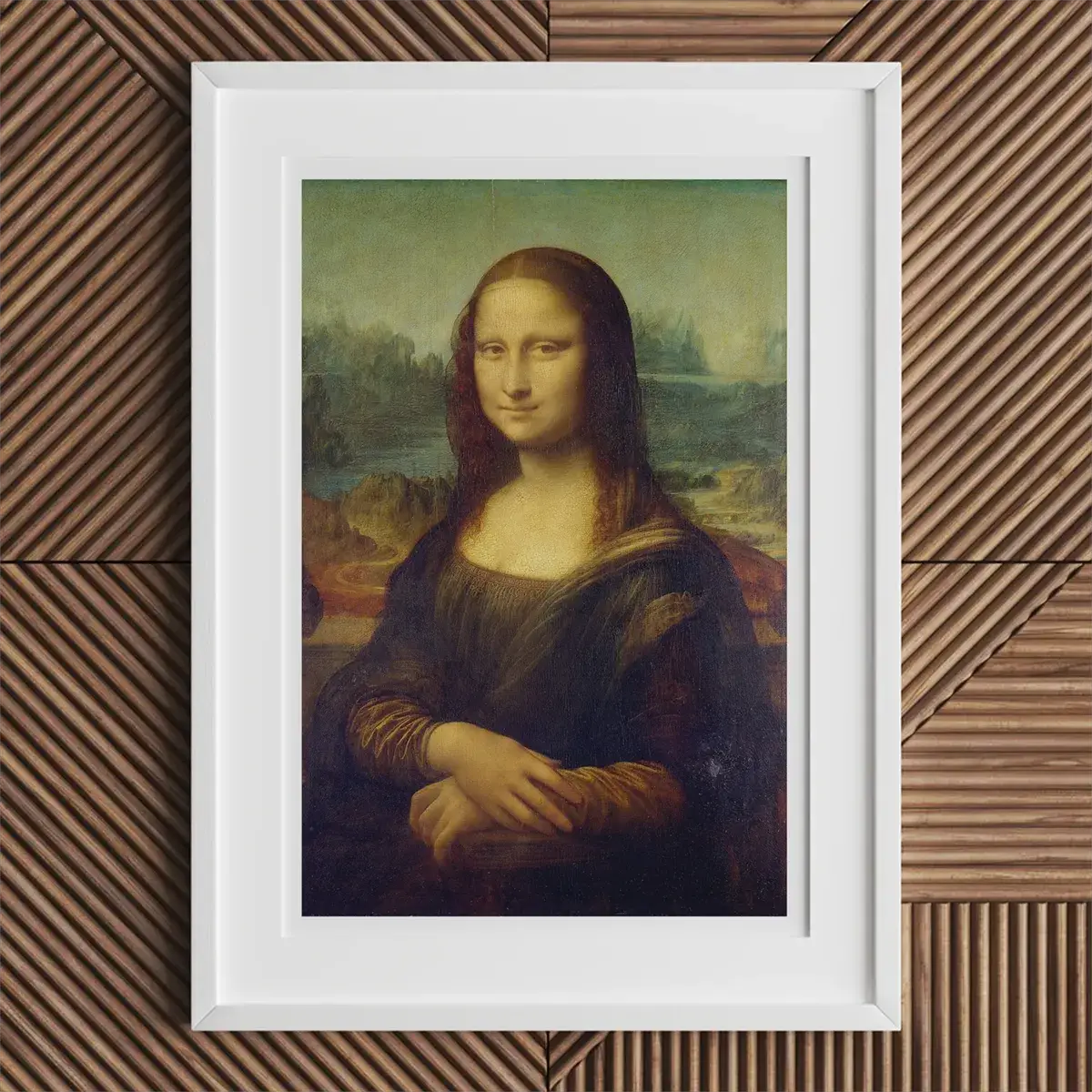

Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa (ca. 1503-1519)

The Shadow of Melancholy

No exploration of Leonardo’s psyche would be complete without asking: beyond ADHD, what of his mood and mental health? Historical records don’t indicate overt depressive disorder or psychosis. Leonardo appears to have been mostly even-tempered, famously composed in demeanor. Yet, there are hints of anxiety and perfectionism that haunted him.

After leaving Rome in 1516, feeling unappreciated by younger rivals like Michelangelo and Raphael, da Vinci accepted an invitation from the King of France. At the French court in Clos Lucé, Leonardo was treated honorably as a living treasure, but his physical health declined.

A generous pension bought him quiet, yet the notebooks of these final years vibrate with a different frequency—less comet flash, more low lunar tide. Lines grow terse: “So many projects. So little finished.” And beneath the ink, scholars detect a slow-beating undertone of mood disturbance.

Leonardo never fit orthodox piety. His theology spun through hydraulics and anatomy. Yet late fragments wrestle with mortality and frustration. On mortality: “Time stays long enough for anyone who will use it, yet I have not.” Worse, he lamented that, “I have offended God and mankind for not having labored in art as I should have”. Expressing self-doubt about his accomplishments despite his fame. Relentless self-critique was the flip side of his lofty curiosity.

Some scholars suggest he experienced “melancholia” (Renaissance terminology for a depressive temperament) especially in older age, as he reflected on unfinished ambitions. Such harsh self-assessments support this. And that hypercritical self-appraisal is often seen in adults with ADHD, who are aware of their lapses and can develop low self-esteem or chronic anxiety as they ruminate over what might have been.

And then there's the question of bipolarity. Some 21st-century psychiatrists float an alternate speculation to ADHD. That cyclical elevations and crashes in Leonardo’s productivity resemble bipolar II hypomania. They point to explosive bursts—dissecting thirty cadavers across two winters, the fever-dream engineering stint for Cesare Borgia—followed by troughs of indecision.

Hard evidence is scant, of course: letters mention insomnia and prodigious energy but no psychotic features or reckless spending. The melancholy passages likewise lack the psychomotor effects typical of severe bipolar depression. Still, the hypothesis reminds us that Renaissance categories of “melancholy” covered a pharmacopeia of affective states we now parse more finely.

And considering this is an open question in itself, most clinicians today recognize untreated ADHD in adults can also lead to restlessness, mood swings, and a chronic sense of underachievement i.e. the feeling of “not living up to one’s potential” despite obvious talent. Well, Leonardo’s late-life letters and marginalia echo some of these sentiments.

Crucially, he did not descend into bitterness or madness; Leonardo's “unquiet mind” remained a well-spring of wonder until the end.

Social Isolation in the Court Bubble

Clos Lucé was comfortable, yet provincial compared to the polymath racket of Milan. Leonardo’s notebooks lament that the French entourage “cares more for hunting than geometry.”

Social disengagement is a known accelerator of late-life depression in neurodivergent elders who rely on intellectual stimulation for dopamine regulation.

Melzi remained a loyal companion, but many Milanese pupils were gone, and Michelangelo’s scathing competitiveness still echoed from Rome.

Even court festivities could sting: one banquet featured an aerial automaton—essentially a knock-off of Leonardo’s earlier theater machines—built by younger engineers. Watching his own innovations re-performed without him may have sharpened the self-dubbed verdict of having “not labored enough.”

Not all was gloom and gloom, though. Far from it. Ambassador de Beatis also notes Leonardo’s “gentle cheer” while explaining anatomical models to visitors. And King Francis admired him so deeply that he built a connecting tunnel from the Château d’Amboise to Clos Lucé for easy visits.

Stroke of Silence

The winter of 1517 settled over the Loire Valley like damp velvet. Leonardo da Vinci, now sixty-five, occupied the manor of Clos Lucé as King Francis I’s “first painter, architect, and engineer.”

Sometime that year a cerebrovascular event seized Leonardo’s right hand—the very instrument that once coaxed sfumato skin from pigment dust. Contemporary ambassador Antonio de Beatis recorded the aftermath: the maestro could still teach and converse “with admirable eloquence,” yet the paralysis ended his painting career.

Modern neurologists map the lesion to a probable sub-cortical infarct; psychologists note that creative adults with late-life disability often experience mood dysregulation as identity frays. In Leonardo’s case, the physical stillness amplified an already-present oscillation between fervor and self-reproach.

Still, even as his right-hand paralysis advanced, Leonardo mentored young architects on canal locks, dictating notes Melzi transcribed.

Occupational-therapy research shows that purpose can buffer depressive symptoms in elders with physical and neurological impairment. In this, Leonardo’s final chapter offers a proto-clinical lesson: adapt the workflow, maintain the wonder.

Last Will and Cognitive Echo

On 23 April 1519, Leonardo composed his will, distributing paintings and granting Melzi stewardship of the notebooks. The act itself suggests organized thought—counter-argument to any claim of severe cognitive decline. Ten days later he died, likely of another stroke.

Whether the oft-painted tableau of Francis I cradling the maestro is myth, the affection was real: the king called Leonardo “a man who has never had an equal, and will never have one.”

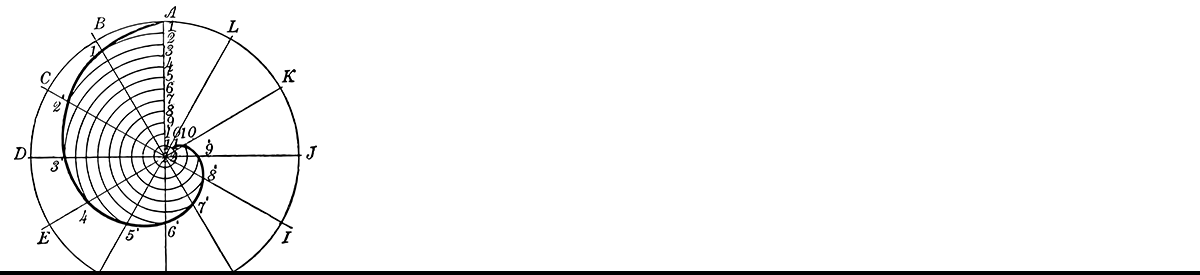

Modern readers hunting for da Vinci depression quotes often stop at the “offended God and mankind” line. Yet his final codex ends not with lament but with geometry: a diagram of intersecting spirals and the note “così si move la mente”—“thus the mind moves.” Even dusk could not still the gyroscope.

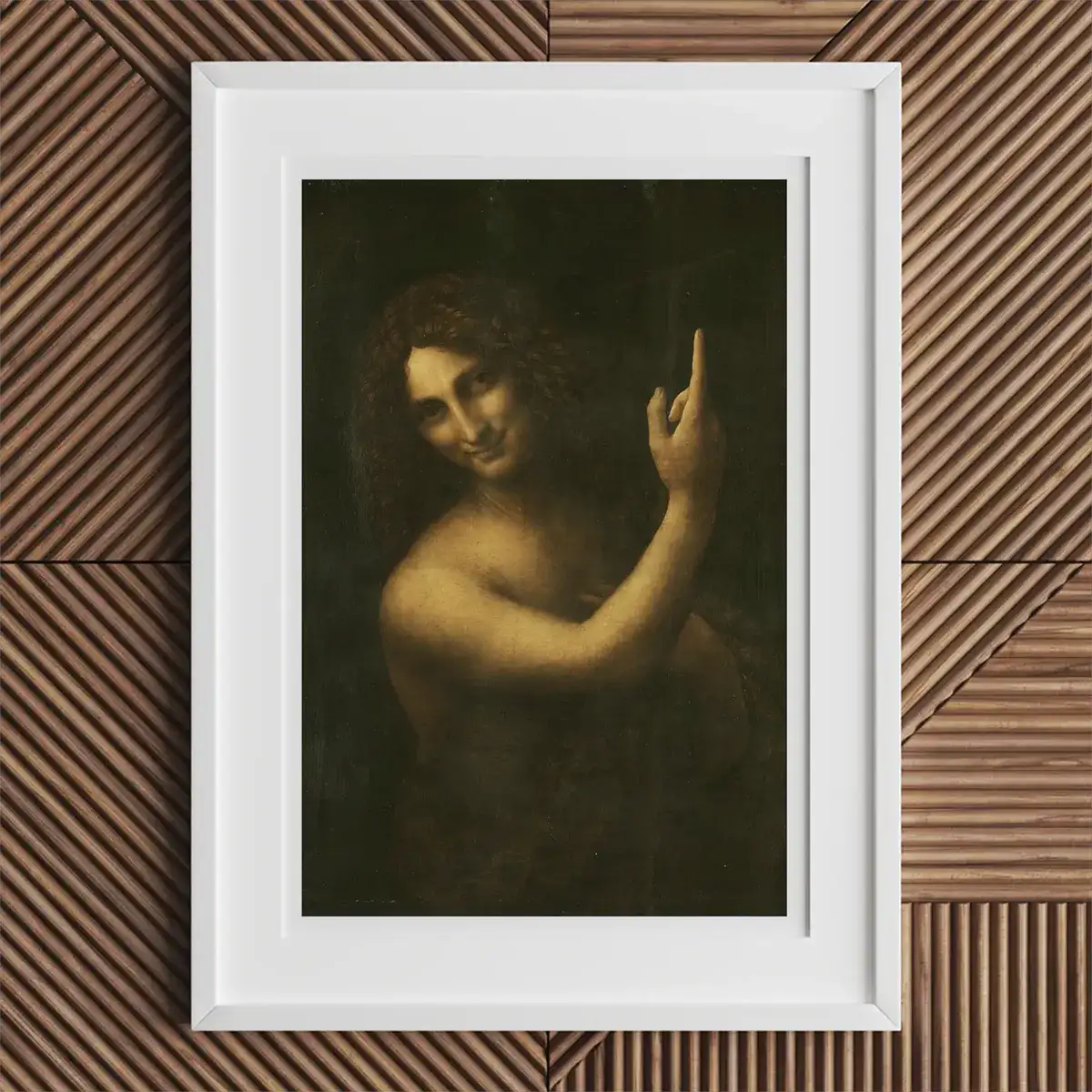

Leonardo da Vinci, St John the Baptist (ca. 1513 - 1516)

Legacy of a Restless Genius

On May 2, 1519, Leonardo died at the age of 67, reportedly cradled in the arms of King Francis I. The Loire mist clung to Clos Lucé while notaries tallied da Vinci’s effects: three finished paintings, trunks of manuscripts, anatomical boards brittle with candle smoke, a mechanical lion’s dented hide.

He left behind trunks full of notebooks and drawings—a treasure trove of an unfiltered mind. These papers would take centuries to be fully deciphered and appreciated, and many were scattered or lost. The world initially remembered Leonardo primarily for his surviving paintings, but the fuller scope of his contributions only emerged later.

The inventory looked sparse beside the mountain of projects he began, yet history now measures his impact less by completed artefacts than by the kinetic architecture of his mind. And in a sense, Leonardo’s legacy was as unfinished as his works: his scientific discoveries (like accurate depictions of the heart valves) lay unpublished and thus didn’t directly influence contemporaries.

Five centuries later, conservation labs, robotics teams, and medical illustrators still mine his folios for blueprints. If the preceding chapters traced attention that flitted, this one asks: what survived, and why does it still matter?

Well, open any cardiovascular textbook and you will find engraving plates hauntingly similar to Leonardo’s heart-valve drawings, reproduced almost line-for-line in 21st-century colour. Though unpublished in his lifetime, those sheets anticipated William Harvey’s circulation model by a century and a half.

In aeronautics, the helical air-screw sketched in 1486 prefigures thrust principles that would not lift Sikorsky prototypes until 1939. Art-historical method likewise carries his watermark: his treatise fragments arguing that shadow owns colour as surely as light underpin modern colour-theory courses.

Infra-red scans of The Last Supper reveal pentimenti layered like geological strata, each adjustment refining perspective mathematics new to mural practice. And because so much of Leonardo's work lies unfinished, his archive functions today as an open-source prototype library. Orthopaedic implant designers adapt his pulley-tendon mechanics; disaster-mitigation experts cite his Deluge ink-storms to model fluid turbulence; machine-vision scholars study his shading rules for non-photorealistic rendering.

Each application of da Vinci's genius demonstrates a strange dividend of incompletion: loose schematics invite reinterpretation. Had he closed every file into a polished monograph, posterity might revere the books while overlooking the doodles—the very zones where lateral transfer thrives.

And a neuro-inclusive reading recognises that external organisers can complement restless innovators. Encouraging such partnerships today—design engineer teamed with timeline-oriented project manager, for instance—echoes the Melzi-Leonardo symbiosis and maximises output without forcing minds into neurotypical moulds.

Neurodivergence as Cultural Catalyst

Current discourse on neurodiversity reframes traits once pathologised. Cognitive-science teams modelling creative networks note that divergent-attention profiles explore conceptual space with larger random walks, encountering far-flung nodes typical thinkers miss.

Leonardo’s notebooks embody this algorithm: from hydraulic scribbles flow arterial insights; from bird-wing doodles, load-bearing arches; from a study of smile asymmetry, the Mona Lisa.

Standing before Mona Lisa in 2025, one confronts not just a portrait but an artefact of cognitive weather: hundreds of micro-adjustments to lip curvature, each a data point in an internal experiment about how humans decode emotion.

That the painting still attracts biometric scanners and poetry attests to a feedback loop: a neurodivergent gaze sought subtlety, crafted ambiguity, and thereby trained generations to look more closely at themselves.

Critically, recognizing Leonardo’s neurodivergence does not diminish his accomplishments. Instead, it humanizes him. It allows us to appreciate that the Renaissance’s most celebrated polymath grappled with mental constraints much like people do today.

And just imagine Leonardo in our time: perhaps he’d be a poster child for gifted children with ADHD, navigating a school system that doesn’t know quite what to do with a student who builds robots in class but forgets his homework.

One can easily envision him as an eloquent advocate for cross-disciplinary education, or as a tech entrepreneur constantly brainstorming (and pivoting) new ventures. The exercise of situating Leonardo in a modern context underscores how timeless his neurocognitive profile seems – the mix of brilliance and frustration, of visionary thinking and everyday stumbling.

Perfectionism, Procrastination, and Value Added

Modern ADHD literature stresses “rejection-sensitive dysphoria”—an acute emotional response to perceived underperformance. Leonardo’s lifelong perfectionism likely intensified that phenomenon. Always seeking room for improvement because good can never be great and great will never be good enough.

Witness his last-minute tweaks to Mona Lisa years after leaving Florence. He reportedly toted the portrait even to royal banquets, adding microns of glaze while courtiers danced. This perpetual refinement suggests an internal barometer forever reading “not enough.” A cognitive weather front often co-morbid with attention-regulation disorders and depressive episodes. It also stymies project completion... making Leonardo's trail of unfinished work even more understandable.

Such existential arithmetic is common in perfectionistic creatives confronting finitude. Of course, there have been many theories across the centuries. Freud’s 1910 monograph argued that Leonardo's unfinished paintings masked childhood repression. While modern neuroscientists counter that executive-function bottlenecks created backlog, and backlog begot guilt. Whatever the case may be, da Vinci's emotional residue manifests in entries describing dreams of floods, decay, and cosmic judgment.

So, a puzzle lingers: would more have survived had Leonardo mastered project management and emotional regulation? Possibly – counterfactual spreadsheets miss how his ceaseless revisions deepened the few works he did complete. And Leonardo’s storied procrastination often served as seasoning rather than stalling, especially in portraiture where nanoscopic glaze passes summon skin that seems to breathe.

Lessons for Contemporary Creators

Educators coaching students with attention-regulation differences now invoke Leonardo as paradigm: show your process, annotate obsession, let cross-pollination bloom. The message counters a lingering stigma that equates Leonardo’s mental health challenges with disorder alone.

For artists wrestling their own “unquiet minds,” Leonardo’s legacy offers both solace and strategy. Solace, in knowing that executive friction need not negate world-historical impact. Strategy, in witnessing his self-hacks: polyphasic naps, to-do lists spliced with passion prompts, obsessive diagramming to externalise working memory.

Mental-health clinicians now integrate such Renaissance precedents into ADHD coaching protocols—embedding micro-curiosities beside mundane tasks to co-opt dopamine pathways.

His life argues that accommodation plus curiosity can flip limitation into leverage. Yet the maestro’s late-life melancholy also warns that unsupported perfectionism corrodes wellbeing. Modern therapeutic frameworks stress scaffolding – deadlines paired with flexible methods – to guard against burnout in neurodivergent talent.

Coda—Spiral Unfinished, Impact Complete

Leonardo’s signature spiral, etched in countless margins, never closes; it simply tapers into infinity. Scholars interpret it as fluid-dynamic shorthand, a cosmic diagram, or an emblem of eternal inquiry. Perhaps it is also a self-portrait of cognition perpetually arcing, never settling.

The irony is that this incompletion is the completion: the open line invites others to pick up the stylus and continue, exactly as aerospace engineers, medical illustrators, and digital artists still do.

The legacy of a restless genius thus transcends any single artefact; it lives in the ongoing circulation of his unfinished thoughts through modern innovation.

Leonardo da Vinci, Lady with an Ermine (ca. 1489–1490)

Renaissance Art, Modern Science

A May sunrise floods the Loire, gilding the chapel at Amboise where Leonardo lies entombed. Five centuries on, drones trace the same river bends he once sketched by candlelight, while neural-net algorithms deconstruct Mona Lisa’s smile pixel by pixel.

Across those centuries arcs a single proposition: that art and science belong to one continuous fabric, a tapestry woven most fluently by minds willing—or wired—to leap every seam.

Consider his favourite diagram: the logarithmic spiral. Mathematicians show that its arms expand yet never meet a boundary—scale-agnostic, self-similar, eternally unfinished. The sketch doubles as cognitive autobiography: projects unclosed but ever widening, tracing vectors others would later extend. And when climate scientists model hurricane eyes, or UX designers study user-attention heat maps, they walk those widening spirals.

Renaissance ↔ Right Now

Open any modern design studio: whiteboards bloom with anatomical sketches beside software equations, fluid-dynamics diagrams shade into colour-grading palettes. This cross-pollination feels avant-garde, yet it is vintage Leonardo. He transported bird-wing curvature into bridge arches, borrowed river vortices for arterial theories, and treated pigment layering like geological strata.

Contemporary cognitive-innovation research confirms that such “domain permeability” flourishes in brains primed for novelty-seeking and high associative range—traits overlapping with attention-regulation differences.

By re-centering Leonardo as prototype of neurodivergent creativity, twenty-first-century educators legitimise cross-disciplinary curricula once dismissed as dilettantism.

The Archive Comes Online

Digitisation now unwraps Codex Atlanticus folios at resolutions Leonardo never saw. Engineers at MIT 3-D-print his coiled-spring car; cardiologists animate his heart-valve cutaways to model turbulent back-flow.

Each resurrection underscores how an unfinished notebook can outlive any finished canvas. Psychologists studying “productive incompletion” cite Leonardo as empirical proof that provisional artefacts serve as modular ideas for future assemblers.

What corporate R&D labels open-innovation ecosystems—the maestro practised with quills and walnut ink.

Neurodiverse Advocacy and Policy

In 2024 the European Union funded Project Codex, a neuro-inclusive tech incubator explicitly invoking Leonardo’s working style: quick-sketched prototypes, mentor scribes partnered with divergent ideators, flexible deadlines anchored by iterative showcases. Early metrics show increased patent filings without drop in completion rate.

Policy architects credit the model for reframing ADHD not as organisational deficit but as ideational surplus requiring scaffolding. Leonardo’s late-life collaboration with Melzi—scribe paired with spark—thus becomes case study for twenty-first-century labour design.

The Ethics of Myth-Making

Hagiography carries risk. To romanticise neurodivergence as automatic genius ignores hardship—the stroke-shaken hand, the self-reproach etched in final notebooks, the income lost to abandoned commissions.

Modern disability scholars urge a balanced narrative: celebrate output while acknowledging structural barriers that magnify executive challenges. Leonardo thrived largely because wealthy patrons tolerated his erratic cadence.

The lesson for contemporary institutions is clear: accommodate cognitive variance systemically, not serendipitously.

The Everlasting Loop

So where does the ledger fall? Leonardo the procrastinator left patrons exasperated; Leonardo the polymath seeded anatomy, optics, hydrology, civil engineering. The same attentional variability that jammed delivery schedules also cross-wired silos no master’s guild had bridged.

In neurological terms, his default-mode network may have run hotter, his task-positive network flickered—but together they drafted blueprints for entire disciplines.

Outcome: an estate of unfinished wonders whose true completion date is permanently deferred to whoever next mines a folio for untapped insight.

In that sense, the grandest collaboration of Leonardo’s life is the one still unfolding: a relay across epochs, each generation inheriting a sheaf of incomplete spirals and daring to spin them further.

The unfinished becomes invitation; the restless mind, renewable engine. Five hundred years after his final stroke, the invitation remains unsigned, evergreen, and addressed to all who think best while orbiting many suns.

Reading List

- Daley, Jason. “New Study Suggests Leonardo da Vinci Had A.D.H.D.” Smithsonian Magazine, June 5, 2019.

- Del Maestro, Rolando F. “Leonardo da Vinci and the Search for the Soul.” John P. McGovern Award Lecture Booklet. Baltimore: American Osler Society, 2015.

- Freud, Sigmund. Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood. 1910. English trans., 1916.

- Isaacson, Walter. Leonardo da Vinci. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018.

- Kemp, Martin. Leonardo da Vinci: The Marvellous Works of Nature and Man. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Nicholl, Charles. Leonardo da Vinci: Flights of the Mind. London: Penguin, 2004.

- Pevsner, Jonathan. “Leonardo da Vinci’s Studies of the Brain.” The Lancet 393, no. 10179 (2019): 1465–72.

- Sandoval Rubio, Patricio. “Leonardo da Vinci and Neuroscience: A Theory of Everything.” Neurosciences and History 7, no. 4 (2019): 146–62.

- Selivanova, Anastasiya S., Ekaterina V. Shaidurova, Konstantin I. Zabolotskikh, and Inna V. Yarunina. “Leonardo da Vinci’s Creativity and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.” In Proceedings of the V International (75th All-Russian) Scientific-Practical Conference: Actual Issues of Modern Medical Science and Healthcare, 763–68. Ekaterinburg: Ural State Medical University, 2020.

- Tola, Maya M. “The Unfinished Works of Leonardo da Vinci.” DailyArt Magazine, April 14, 2025.

- Vasari, Giorgio. Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. 2nd ed. Florence, 1568.