In a sunlit community center one Saturday morning, a circle of women and men sit over embroidery hoops. The only sounds are hushed conversations and the soft snip of scissors, yet something profound is unfolding. In their laps, pieces of fabric slowly transform into protest messages stitched in careful cursive.

You walk through the doorway of this quiet “stitch-in” workshop, activists using needle and thread in lieu of megaphones. Their craftivism drawing curious onlookers like you and gently inviting dialogue about things you'd never have known otherwise. A hands-on gathering where arts and crafts become powerful tools for social justice, threading creativity with empowerment and change for the better.

A chalkboard sign nearby reads, “shhhh… craftivism workshop in progress.” Passersby keep peeking in. Drawn by the unexpected scene of protest art rendered in cross-stitch and crochet instead of chants and picket signs. Witnessing is more than a quaint craft circle... and they know it. Sewing creativity and craftsmanship to empower the powerless. Delighting the eye and soothing the soul. Weaving fabric of a revolution balancing beauty with action, and art with purpose.

Key Takeaways

-

Craftivism harnesses the quiet power of needle and thread to weave profound messages of social change, turning traditional crafts into gentle yet potent acts of resistance.

-

Rooted deeply in the radical ideals of the Arts and Crafts Movement, craftivism bridges art and ethics, reclaiming handmade creation as a moral force for justice and dignity.

-

Across continents and eras—from Chilean arpilleras under dictatorship to Gandhi’s spinning wheel defying empire—craft has served as a courageous, tactile language for communities to voice truth when words alone were perilous.

-

By elevating historically overlooked “women’s work,” craftivism champions gender equity and redefines political engagement through intimacy, creativity, and communal storytelling.

-

Craftivism’s gentle protest and intentional slowness quietly dismantle barriers, cultivating dialogue, empathy, and solidarity stitch by deliberate stitch.

The Threads of History: Art, Craft, and the Pursuit of Social Justice

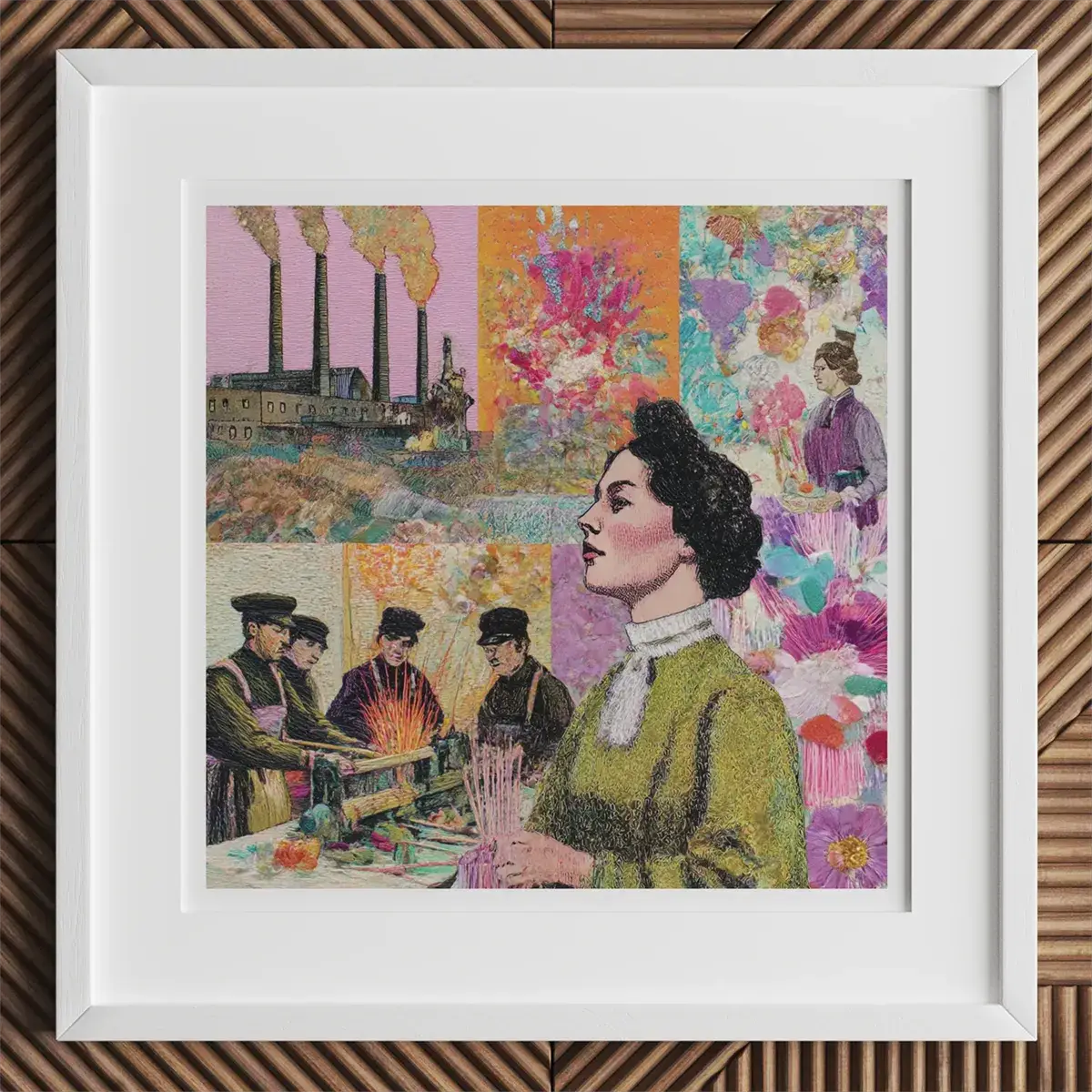

To understand today’s craft-powered activism, one must travel back to Victorian England, where the first threads of arts, crafts, and social justice were woven together. In the late 19th century, amid smokestacks and factory whistles of the Industrial Revolution, a group of idealists rebelled against the dehumanizing march of mass production. They dreamed of a return to handmade beauty, where art would uplift workers rather than alienate them. This was the Arts and Crafts Movement, and at its heart was a radical idea: that art, design, and labor could be harnessed to improve society and the lives of ordinary people.

John Ruskin

An English critic and philosopher, Ruskin was one of the movement’s intellectual fathers. Outraged by the grim factories and shoddy machine-made goods of his day, Ruskin championed a revival of craftsmanship not just for aesthetic reasons, but as an ethical imperative. He believed that beauty, craft, and justice were intertwined, famously arguing that art and design should “promote social justice and improve the lives of working-class people”.

To Ruskin, every carefully chiseled stone or ornate textile carried a moral weight. If crafted under fair conditions by a fulfilled artisan, an object radiated “sweetness, simplicity, freedom” – qualities he felt society desperately needed. But if churned out in a sweatshop, even a decorative object was, in Ruskin’s view, tainted by the injustice of its making.

William Morris

If Ruskin provided the theory, William Morris supplied the practice – and the passion. Morris, a poet, designer, and outspoken socialist, took Ruskin’s ideals and tried to live them. He founded workshops that produced exquisite hand-printed wallpapers, woven tapestries, and carved furniture, insisting on quality over quantity and treating workers as partners in the creative process.

Morris also saw a glaring contradiction: lovingly handcrafted goods were expensive, and thus mostly adorned the homes of the wealthy, not the working folk he aspired to uplift. This paradox at the heart of the Arts and Crafts Movement – that hand-made wares cost more in a market economy, excluding the very people they aimed to empower – only sharpened Morris’s critique of capitalism. As one art historian notes, “hand-made is expensive and so only for the wealthy. The more obvious this contradiction became, the stronger Morris’s socialism grew.”

Morris responded by doubling down on his call for an “Industrial Commonwealth,” envisioning a society where art, labor, and justice entwined. In manifestos and lectures (often delivered to factory workers after their shifts), he argued that meaningful, creative work was a human right, and that a truly beautiful society could only be built on equality and dignity for all artisans.

American Visions

Across the Atlantic, the Arts and Crafts spirit also flickered, though in a somewhat different hue. American designers like Gustav Stickley embraced the movement’s aesthetics – the clean lines of oak furniture, the honest joinery and natural motifs – but often merged them with entrepreneurial zeal. Stickley’s magazine The Craftsman helped popularize Arts and Crafts style among the growing American middle class.

Utopian communities such as Rose Valley in Pennsylvania and the Roycroft campus in East Aurora, New York, sprang up, blending cooperative ideals with commerce. Roycroft’s founder, Elbert Hubbard, unabashedly “combined the ideals of William Morris with the techniques of capitalism”– a sign that in the U.S., the movement sometimes became less about overthrowing industrialism than about selling an anti-industrial chic.

Still, whether in Britain or America, the late-1800s Arts and Crafts ethos carried a germ of radical thought: that art was not merely for museums or elites, but could be a vehicle for social reform. It asserted the then-novel idea that creative labor has intrinsic value – that a potter or weaver deserved as much respect as a painter – and that a well-crafted object could ennoble maker and user alike. This philosophy laid early groundwork for linking arts, crafts, and social justice, even if the full political implications would only be realized in later generations.

The notion that beauty and utility should serve equity and community would resonate in various forms throughout the 20th century and into the present, from Mahatma Gandhi’s spinning wheel to the knitted pink hats of modern protests. But before we leap to those contemporary movements, it’s worth noting another historical thread: the role of gender and craft.

The Profundity of Women's Work

While Ruskin and Morris were railing against factories, countless women on both sides of the Atlantic toiled in the supposedly “minor” arts – needlework, quilting, embroidery – often invisible to history’s gaze. In grand Victorian parlors, women stitched elaborate samplers and table linens; in humble cabins, they pieced quilts to keep their families warm. Such works were dismissed as mere “household crafts,” not fine art. Yet they were among the few creative outlets available to women, and they carried intimate expressions of female experience in their patterns and folds.

Art historians now recognize that women’s experiences were long under-represented in the fine arts, while the domestic crafts that women used for self-expression were deemed unworthy of recognition. Those “ladies’ hobbies” in fact often concealed inexpressible details of female life – joy, sorrow, rebellion – coded into pattern and motif.

The Arts and Crafts pioneers only partially acknowledged this dynamic; William Morris’s daughter May Morris, an accomplished embroiderer, was one of the few women celebrated in the movement. It would take much longer – well into the late 20th-century feminist movement – for traditional “women’s work” to be fully reappraised as not only art, but as a tool of empowerment and resistance. Still, the 19th-century craft revival planted seeds in fertile ground.

By the early 1900s, the idea that craft could carry cultural meaning and even social critique had quietly taken root, even as the world hurtled into an age of mass-manufacture. In the coming decades, disparate groups – from village cooperatives to political revolutionaries – would pick up those threads and weave them into acts of defiance. Where the simple act of making by hand became a stand against injustice. Through quilts, tapestries, and textiles, new voices entered the arena of activism, often unheard by traditional historians but resonant and clear to those who knew how to read their stitches.

Stitched in Resistance: Patches of Protest Across the World

While genteel designers in Europe were extolling craft for its moral uplift, elsewhere on the globe people were deploying craft as direct resistance – sometimes at great personal risk. In settings where speaking out could mean danger or death, the language of fabric and thread provided a cunning alternative. Textiles became chronicles of trauma, memorials to the lost, and banners for justice when conventional protests were suppressed. These instances form a patchwork of global craft activism long before the term “craftivism” was coined. A few notable examples include:

Chilean Arpilleras (1970s–80s)

Under General Pinochet’s brutal dictatorship in Chile, open dissent was perilous. So groups of women – many of them mothers and wives of the “disappeared” – gathered in secret workshops to create arpilleras: small appliqué tapestries that depicted the harsh realities of life under the regime.

Using scraps of cloth and simple stitches, they sewed scenes of military violence, breadlines, and vigil demonstrations, encoding testimonials that Chile’s censored media would not report. These poignant tapestries of the disappeared were smuggled out through church networks and human rights groups, bringing international attention to the regime’s atrocities.

What began as a coping mechanism for grief evolved into a quiet act of rebellion – each stitch a statement that we will not be silenced.

Mothers of Plaza de Mayo (1977–present, Argentina)

In Argentina, during the bloody Dirty War, a group of bereaved mothers similarly turned to symbolism and craft in protest. The Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, seeking information about their missing children, famously marched in Buenos Aires carrying photos and wearing white headscarves embroidered with their children’s names and dates.

The pañuelos blancos (white scarves) became an icon of resistance. Originally, they even used cloth diapers as scarves – a tender nod to the children ripped from them.

The very act of stitching their loved ones’ names onto fabric was an exercise in remembrance and truth-telling. It personalized the political; each name in neat blue script refuted the junta’s denial of the kidnappings and murders.

The image of those dignified women, needles in hand, transforming mourning into a cry for justice, seared itself into Argentina’s collective conscience and the world’s human rights vocabulary.

Sojourner Truth’s Needlework (19th century, United States)

The African American abolitionist and women’s rights crusader Sojourner Truth is renowned for her speeches (“Ain’t I a Woman?”) – but less known is that she also took up needle and thread as instruments of resistance. Truth supported herself in her later years by selling embroidered calling cards and other handicrafts, often with messages of empowerment. As one historian notes, even “the legendary abolitionist Sojourner Truth engaged in knitting and needlework as a form of resistance.”

In an era when Black women’s voices were systematically ignored, the very sight of a formerly enslaved woman practicing a skilled craft – and earning money from it – was subversive. It reclaimed dignity and agency stitch by stitch. Moreover, it symbolically flipped the script: the same kind of needlework once forced upon enslaved women for their masters’ profit was now a tool for Truth’s own economic independence and advocacy. Her handiwork literally carried her image and ideals into the parlors of Northern supporters, spreading her message in an intimate, tangible way.

Mahatma Gandhi’s Spinning Wheel (1920s–40s, India)

Few images capture the marriage of craft and political protest as powerfully as M.K. Gandhi seated at his spinning wheel (charkha). Confronting the might of the British Empire, Gandhi led India’s independence movement with the philosophy of swaraj (self-rule) and swadeshi (self-reliance). Central to this was the boycott of British textiles and the revival of hand-spinning and weaving of khadi (homespun cloth).

Gandhi himself spun cotton each day, and he exhorted every Indian to do the same. What possible impact could this humble act have against an empire? As it turned out, a profound one. The spinning wheel became a symbol in Gandhi’s struggle for India's independence and economic self-sufficiency.

Each thread spun was a thread cut from the colonial economy, a step toward freeing India from dependence on imported British cloth. In a 1941 gesture rich with irony, Gandhi even sent one of his portable spinning wheels as a personal gift to the American industrialist Henry Ford, explaining its significance in the fight for freedom.

The charkha’s power was both practical and symbolic: it unified millions in a common traditional practice, preserved a craft heritage, and asserted a philosophy of nonviolent resistance.

When masses of Indians took up spinning, it was non-cooperation in its most creative form – a nationwide act of crafting as protest. British authorities once dismissed Gandhi’s movement as “the Macramé Revolution,” but they grossly underestimated the resolve behind the yarn.

By the time India won independence in 1947, the spinning wheel had whirred its way into history as an emblem of how a simple handcraft can unravel an empire’s might.

The NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt (1980s–present, United States)

Fast forward to the 1980s in America: a mysterious plague, AIDS, was devastating communities, especially gay and marginalized populations, while those in power largely remained silent. Grief and frustration swelled in equal measure.

In 1987, activist Cleve Jones hit upon an idea both poignant and pointed: a massive community quilt to commemorate those lost to AIDS. Each person would be remembered with a fabric panel, sewn by loved ones, and all the panels would be joined into an ever-expanding tapestry – the AIDS Memorial Quilt.

What began with a few panels grew into a monumental folk-art project; by the 1990s the quilt blanketed the National Mall in Washington, D.C., its colorful 3-by-6 foot panels (the size of a human grave) visually shouting the humanity of the 94,000+ lives commemorated.

The quilt was beautiful, heart-wrenching, and impossible to ignore. As Jones later reflected, “When we created the first quilt panels it was to... demand action from our government. The Quilt has become a powerful educator and symbol for social justice.” Indeed, the soft fabric squares did what years of statistics and protests had struggled to do – they made the crisis deeply personal and visible.

Families, friends, and even strangers found healing in stitching memories of their loved ones, while viewers walking among the panels grasped the enormity of the loss. The project helped shift public perception and policy on AIDS, proving that a collective act of crafting could spur national soul-searching.

To this day, the AIDS Quilt, now weighing 54 tons with nearly 50,000 panels, stands as a living testament to activism through artful memorial. It showed the world that quilting – often dismissed as a quaint pastime – could in fact galvanize a movement and carry the banner of compassion and justice.

•

Spanning continents and decades, these examples underscore a powerful truth: when conventional avenues of expression are closed or insufficient, art and craft can emerge as alternative media for dissent and hope. Whether smuggling out the truth in a tapestry, or building an enormous quilt to humanize a health emergency, marginalized people have repeatedly turned to handmade art as a tool to challenge power.

In each case above, the act of making is inseparable from the message conveyed. The tactile nature of craft – its slowness, intimacy, and accessibility – becomes part of its political potency. As craft scholar Betsy Greer observes, many see “creating something stitch by stitch with their own hands as a stand against mass-produced goods and corporate values.” There is a quiet rebellion in choosing needle and thread over slick mass media or manufactured signs. It says: we will tell our own story, at our own pace, with our own hands.

By the early 21st century, this impulse had coalesced into a recognizable movement, proudly bearing a new name that Greer herself coined around 2003: Craftivism. Blending the historical threads we’ve discussed with new ideas, new media, and new communities. From the gentle protests in the heart of London’s shopping districts to youth-led quilting academies in California, today’s craftivists are expanding the legacy of art-meets-activism in innovative ways. Their story is one of creativity, empathy, and persistence – a reminder, in the words of one Chilean arpillera artist, that “there is no machinery that can erase our creativity”.

The Rise of Craftivism: When DIY Meets Social DIY (Do-It-Yourself Justice)

In the early 2000s, amid globalization’s dizzying pace and the digital revolution, something unexpected happened: handmade crafts surged back into popular culture, no longer just as nostalgic hobbies but as edgy, countercultural statements.

Young people learned to knit in hip “Stitch ’n Bitch” groups; guerrilla knitters yarn-bombed lamp posts and bus stops with colorful cozies; crafters sold subversive cross-stitched samplers online with slogans like “This is what a feminist looks like.”

Out of this ferment emerged the term “craftivism” – a fusion of craft and activism – popularized by writer-activist Betsy Greer to describe “the many ways that craft and activism intersect.” Greer has described how the word arose from “frustration at the rule of materialism... and the continuing quest for the unique” in a world of mass production. It captured a zeitgeist: people yearning to reconnect with tangible creation and to infuse their political engagement with personal creativity.

Craftivism 101

At its core, craftivism is the idea that making things by hand can itself be a political or social act. This might mean directly addressing an issue through the content of the craft (like stitching slogans or symbols of protest), or it might be more about the process and values embodied (like the collaborative spirit of a quilting bee creating a community banner).

Betsy Greer and others in the movement emphasized that craftivism operates in a wide spectrum: it can be “any type of craft that is inspired by politics or is made to address social causes,” from knitting hats for the homeless to embroidering quotes from political dissidents.

Importantly, craftivism is inclusive. Because crafting traditionally has been seen as “domestic” or non-professional, it carries “a lower barrier to entry… it doesn’t have to be beautiful as culturally defined, and it doesn’t have to go up on a wall – so there is less pressure to be ‘good’”.

As Greer notes, this means anyone can be a craftivist; you don’t need an art degree or a gallery show, just the willingness to make something with heart and purpose. In a way, craftivism democratizes art as activism. It invites people who might never join a loud protest march or publish an op-ed to instead pick up a needle, hook, or brush and start “creating personal, social, and political change – stitch by stitch.”.

Gentle Protest: The Craftivist Collective’s Approach

One of the shining examples of modern craftivism in action is the Craftivist Collective, founded in 2009 by British activist Sarah Corbett. Hailing from a family of Liverpool labor organizers, Corbett was a seasoned campaigner in conventional activism but began feeling burnout and disillusionment with adversarial tactics. On a long train ride in 2008, she brought along an embroidery project to pass the time – and had a personal epiphany.

The slow, calming act of stitching not only soothed Corbett's anxiety but gave her space to reflect. “The repetitive action of cross-stitching made her aware of how tense she was… It gave her space to ask herself whether she was really being effective, or just doing lots of things to feel effective,” she later recounted.

Realizing that craft could fill a need for contemplative, kind activism, Corbett developed what she calls the “art of gentle protest.” Corbett formed the Craftivist Collective to put these ideas into practice, rallying makers to address social issues in a quieter but deeply intentional way. The Collective’s campaigns illustrate how craftivism differs from – and complements – more confrontational activism.

In 2016 Corbett and her team took on the issue of poverty wages at a major retailer. Instead of picketing or boycotting, they launched the “Don’t Blow It” campaign targeting Marks & Spencer (M&S), a British retail giant, urging its board to pay employees a living wage.

Craftivists across the UK hand-stitched messages on elegant M&S handkerchiefs, with polite but pointed encouragements like “Please, don’t blow your chance to do the right thing!” Each hanky was painstakingly made by a customer who was also a concerned citizen. They even held public “stitch-ins” outside M&S stores – friendly picnic-style gatherings where activists sat and stitched in public view. This non-threatening scene invited shoppers to inquire and chat, spreading awareness in a disarming way.

After weeks of this gentle pressure, Craftivist Collective members secured private meetings to present the gift-wrapped hankies to M&S board members, speaking from a place of respect and shared concern rather than accusation.

The result? The board, already aware of the campaign from media coverage it attracted, publicly endorsed moving toward a living wage at the company’s shareholder meeting. Soon after, M&S granted pay raises impacting 50,000 workers. It was a stunning success for a campaign that never shouted a slogan or carried a single picket sign. Demonstrating the power of craft’s approachability.

Conveying earnest concern and aesthetically engaging messages, the craftivists opened up dialogue where others might provoke defensiveness. Through creativity and empathy, they turned boardroom targets into partners, achieving change that combative protest alone had failed to win.

Other Craftivist Collective projects have been equally imaginative. They’ve made miniature protest banners with sweet illustrations and hung them at bus stops and universities to spark thought on issues like climate change — the small size forcing the viewer to lean in and read, a subtle invitation rather than an aggressive billboard.

An initiative with the Fashion Revolution stands out — a campaign where craftivists slipped handwritten scrolls into the pockets of clothing in stores, bearing messages about the hidden human cost of fast fashion – e.g. “Our clothes can never be truly beautiful if they hide the ugliness of worker exploitation.”. Shoppers later found these secret notes, prompting them to consider who made their clothes and under what conditions.

This gentle guerrilla tactic received wide media attention, even in fashion magazines that usually shy away from labor rights topics, precisely because it was so unexpectedly creative and non-confrontational. Corbett calls this effect “intriguing the un-intrigued.” By avoiding guilt-tripping or scolding, the craft interventions piqued curiosity and appealed to people’s values without making them defensive.

The Craftivist Collective’s methods, rooted in kindness, beauty, and humility, exemplify what researchers describe as the “affective micropolitics” of craftivism. Instead of measuring success only in headline-grabbing moments or policy wins, craftivism values the small-scale impacts: the meaningful conversations sparked, the personal reflections inspired, the incremental shifts in attitude – what theorists might call “minor gestures” that cumulatively work on the “major” structures from within.

Academic studies of craftivist organizers find that these micropolitical acts generate affective connections between people, materials, and ideas, helping new coalitions and understandings to emerge. In other words, by making activism more hands-on and human-scaled, craftivism opens doors for those who might feel alienated by confrontational politics.

It’s a way of doing activism that is accessible and emotionally intelligent, yet no less ambitious in its aims for systemic change. “Activism through the eye of a needle,” Corbett quips, “can be stronger than activism through megaphones” – because it fosters listening and empathy on all sides (even among the powerful) rather than entrenching an us-versus-them divide.

“Craft + Activism = Craftivism”: A Tapestry of Causes

Beyond the Craftivist Collective, the craftivism movement is as diverse as the array of crafts it encompasses. It has no singular leader or agenda; rather, it’s a loose philosophy that anyone can adapt to their own causes. Feminism, unsurprisingly, has been a major thread from the start – indeed, Greer’s pioneering book Knitting for Good framed craftivism in part as a third-wave feminist reclaiming of the domestic arts.

In the 21st century, many women (and allies) have used traditionally “feminine” crafts like knitting, sewing, and embroidery to push back against sexism and gender norms. One of the most visible moments was the 2017 Women’s March, which became a sea of pink “pussyhats” – hand-knit and crocheted caps worn by thousands as a bold statement of solidarity and protest against misogynistic rhetoric.

The Pussyhat Project, co-founded by Jayna Zweiman and Krista Suh, distributed knitting patterns for these hats worldwide ahead of the march. It aimed to make a powerful visual impact (which it did, flooding news broadcasts with a symbol of unity) but also to engage novice activists.

For countless people who couldn’t travel to D.C., knitting a hat for someone who could attend became a meaningful way to participate. This global craft effort turned an insult into empowerment and demonstrated the scalable, viral potential of craftivism in the social media age. As one craftivist quipped, “we weaponized Grandma’s knitting needles for women’s rights” – with a smile.

Craftivism has also been embraced by environmental and climate justice advocates. Quilting, mending, and upcycling are inherently about sustainability – reusing materials, valuing what we have – and activists have leveraged that philosophy. The “Welcome Blanket” project (also spearheaded by Jayna Zweiman after the Pussyhat success) invited crafters to knit or crochet blankets for immigrants and refugees, each blanket accompanied by a note to the recipient.

Apart from providing literal warmth, the project advocated for more compassionate immigration policies by highlighting immigrant stories and needs. In its first run, over 2,000 blankets were made and exhibited in a museum before being distributed as gifts to new immigrants – a poignant mix of political statement and humanitarian aid.

Climate activists have also organized knit-a-thons to create massive patchwork banners for climate marches, or yarn-bombed trees in threatened forests to draw attention to conservation. The tactile, slow nature of these crafts stands in stark contrast to the fast-paced consumption driving environmental destruction, embodying a call to slow down and cherish the planet’s resources.

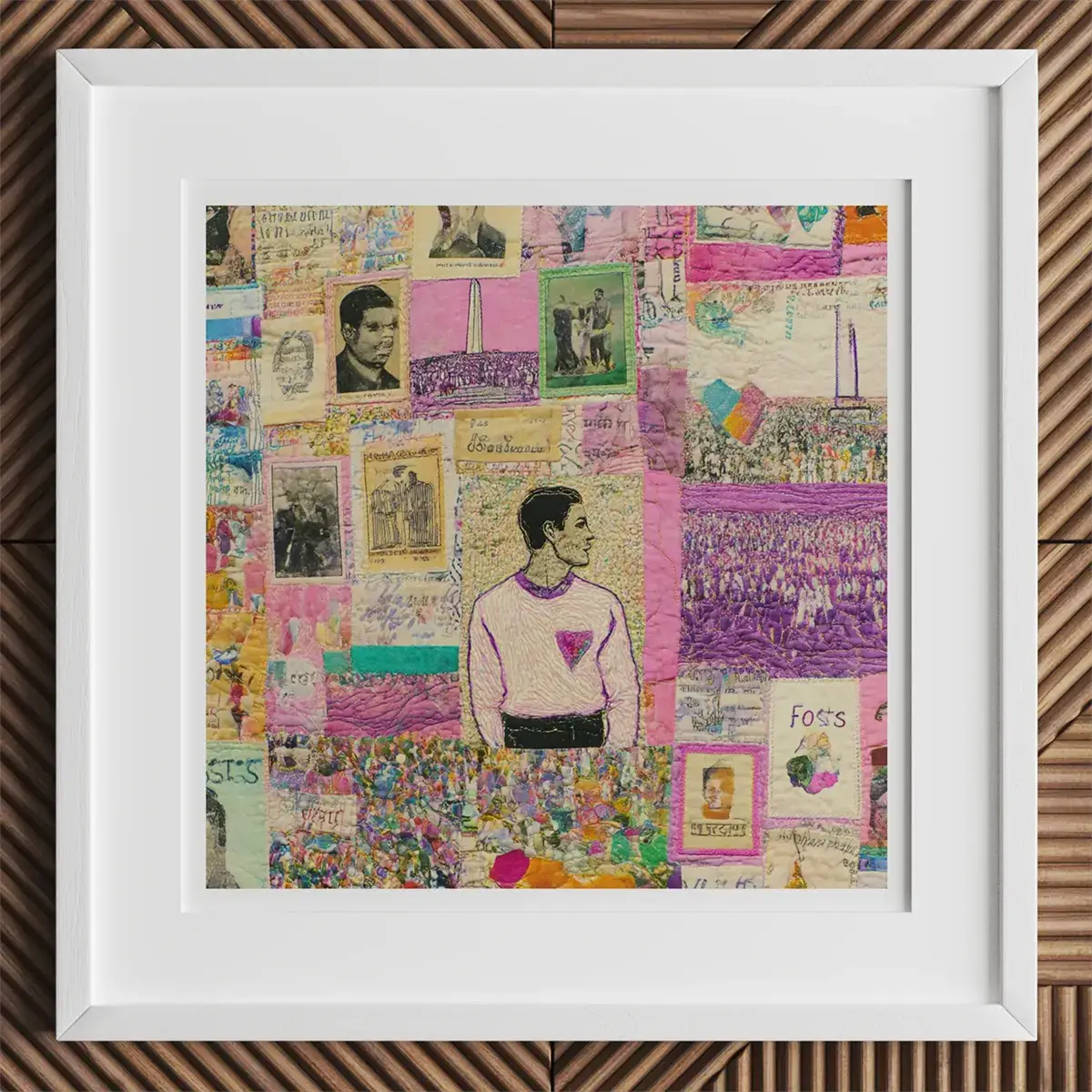

Perhaps most inspiring is how craftivism has engaged youth and marginalized communities in speaking out. Consider the work of Sara Trail, a young African American quilter who in 2017 founded the Social Justice Sewing Academy (SJSA). Trail recognized that quilting – a traditional craft – could become a radical platform for urban teenagers to express their experiences with issues like racism, violence, and inequality.

Through SJSA workshops, teens design and sew quilt blocks that reflect their personal social justice messages: one block might memorialize a friend killed in a shooting, another might depict a raised fist or a plea for racial equity. These blocks are then sent to volunteers around the country who embroider and quilt them into large collaborative quilts, which are exhibited nationally.

The impact is twofold: young people, often unheard, get to see their stories validated and elevated through art, and audiences are confronted with youth perspectives in an unignorable format – a colorful quilt hanging in a gallery or community center, crying out with fabric and thread for a better world. Trail has noted that many of the teens who join SJSA have never sewn before, but they quickly grasp the power of the medium.

The process of stitching their truth can be healing and empowering in itself. One student’s patchwork portrait of a protest and the words “No Justice, No Peace” not only helped her process anger at injustice but also communicated that message far beyond her neighborhood when the finished quilt toured museums.

Projects like SJSA show craftivism coming full circle to its educational roots – much like quilting circles of old passed down skills and stories, these modern circles teach critical thinking, community organizing, and empathy, all through hands-on creativity.

Meanwhile, communities affected by incarceration, illness, or trauma are also finding solace and voice in craftivism. In the disability rights arena, for instance, activists have created cross-stitched pieces that ironically mimic the signage of accessible bathrooms or the international wheelchair symbol, but with added text that calls out ableism.

In prisons, some art rehabilitation programs encourage inmates to take up crochet or painting; a number of incarcerated artists have used their work to depict the social injustices of the prison-industrial complex — the Confined Arts, a project by formerly incarcerated people, showcases such voices.

Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, when millions were stuck at home, craftivism found new purpose: people sewed face masks not only as mutual aid but some embroidered messages on them – “Thank You Essential Workers” or “Mask Up for Justice” – turning a public health tool into a mobile protest message.

In 2020, mask-making collectives emerged that donated thousands of masks to vulnerable communities and simultaneously advocated for healthcare equity and workers’ rights. It was yet another instance of how the act of making and giving can knit communities together and spotlight social issues.

The Fabric of Change: Why Artisanal Activism Matters

As we’ve journeyed through these stories – from Victorian workshops to digital-age craftivist campaigns – a pattern emerges. Arts and crafts, long relegated to the sidelines, have proven to be powerful vehicles for social change when wielded with vision and heart. They bridge divides: between artist and audience, between activist and bystander, between the personal and the political. They appeal to our sense of beauty and creativity, drawing us in, and then challenge us to think and feel more deeply about injustice.

In an era of polarized debates and high-decibel news cycles, the quiet persistence of craft can seem anachronistic – yet perhaps that is exactly its advantage. It disarms us, literally and figuratively. As activist Elizabeth Vega puts it, “oftentimes we are fighting against things… but art reminds us of what we’re fighting for – connection, beauty, humanity, and the ability to create and dream and collaborate.”

In Vega’s community work in St. Louis after the Ferguson unrest, she saw how creating art together allowed people to process trauma and find common ground. A simple memorial quilt or painting session could achieve what heated arguments could not: healing, understanding, a shared sense of purpose.

The literary lyricism of craft – its metaphors of weaving, mending, threading – also offers a powerful language for reimagining society. When we speak of “re-weaving the social fabric” or “threading voices together,” those are not just pretty phrases; they echo the real, material actions of craft. After all, to craft something is to care for it, to give it time and attention.

Imagine if we approached social justice the same way: patiently, inclusively, crafting solutions with care rather than force. The craftivists profiled here show that this is not a naïve fantasy but a viable strategy. They have secured labor rights, commemorated marginalized histories, and built global networks of solidarity one stitch at a time.

That said, this movement is not without its challenges and critiques. One concern is that the resurgence of interest in craft (the so-called “artisanal boom”) can be co-opted by consumerism. We see “craft” beers and “artisanal” branding everywhere, often divorced from any social purpose – more lifestyle statement than activism.

Scholar Alanna Cant warns that a gentrified craft culture, focused on upscale markets, can inadvertently reinforce class and economic hierarchies: “The renewed interest in craftwork is driven by upper-middle-class dispositions that lightly critique – but do not reject – industrial capitalism… marked by taste and aesthetics rather than political lives.”

If craft’s value is only seen through pricey products, the actual artisans (often poor or marginalized) may remain invisible or underpaid. Craftivists are aware of this tension. Many explicitly try to avoid turning their work into commodities; they give it away or display it publicly rather than selling, to keep its focus on the message not the market.

Moreover, some craftivists work to include those very overlooked artisans in the conversation – for example, fair trade craft organizations and cooperatives that empower indigenous makers, or collaborations between contemporary artists and traditional craft communities that share skills and profits equitably.

Craft is political—holding a mirror up to the craft world itself, pushing it to be mindful of who is (and isn’t) uplifted when we celebrate the handmade. After all, if we relish a handwoven rug as a symbol of anti-industrial values, we must also care about the weaver who made it and whether she earns a living wage. In short, the social justice ethos must extend to the act of craft production itself, not just its end use as protest art.

Another challenge is to ensure craftivism remains inclusive and forward-thinking. Traditionally, crafts were segregated by gender, culture, and class – an unfortunate legacy that must be overcome. It’s encouraging to see men taking up knitting in activism (e.g. some male veterans knit for peace to deal with PTSD), and women welding metal sculptures for social causes, breaking craft gender norms.

It’s likewise crucial to honor crafts of diverse cultures (from African American quilt storytelling to Indigenous beading) within the movement, avoiding a purely Eurocentric “yarn and tea” image. In this regard, the intersectional lens from feminism has helped craftivism consciously address issues of race, sexuality, and identity.

As Rachel Fry’s research revealed through interviews with craftivists around the world, the movement is grappling with how gender, race, and class shape the practice, aiming to ensure “craftivism is a diverse art form with a broad range” of participants and styles.

There is active dialogue in the community about representation – for instance, acknowledging that quilting as activism has deep roots in African American history (the quilts of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, or the coded Underground Railroad quilts lore) and Native history (such as the Lakota ceremonial quilts called star quilts, often given as honors or protests). By learning from these rich heritages, contemporary craftivists add depth and authenticity to their work.

In the end, what makes the fusion of arts, crafts, and social justice so compelling – and effective – is its dual nature. It operates both softly and sharply. Soft in its welcoming, hands-on, humane approach; sharp in its pointed messages and its challenges to injustice. A protest embroidered on cloth may fray at the edges, but its impact can linger in the mind like a vivid dream – perhaps longer than a shouted slogan that fades from memory. A communal art project may not instantly change a law, but it can change individuals, who then go forth and change laws.

Crucially, craftivism also brings joy and beauty into spaces of struggle, which can sustain activists for the long haul. The act of creation is inherently hopeful – to craft is to believe in tomorrow, to invest time in a vision. As we face daunting social justice challenges, this infusion of hope is no small thing. It is akin to planting seeds. The Chilean women who sewed their secret protest tapestries during dictatorship couldn’t march in the streets, but they planted seeds of truth in each arpillera, seeds that eventually helped bring about change and healing in their country. Those seeds germinate slowly, but firmly.

Consider one final scene: A group of neighbors gather in a library after hours for a community quilting night. On the table are stacks of fabric squares and baskets of thread. These neighbors come from different backgrounds – different ages, races, political leanings – and many have never met before. But as they sit and begin stitching squares (each square perhaps depicting something they love about their town, or a change they wish to see), conversation flows. Walls break down.

A retired engineer learns from a teenage activist about the need for a new youth center; the teen learns from the elder about the town’s history. By the end of the evening, they have not only made progress on a collective quilt, but also on understanding each other. They decide to lobby the city council together for that youth center, bringing the nearly finished quilt as a visual testimony of their united community. In this simple act of making and sharing, art has done what rhetoric alone often struggles to do – build trust, imagination, and solidarity.

Such is the quietly transformative power of the arts-and-crafts alliance in social justice. It reminds us that movements are made of people, and people respond to stories, symbols, and shared experiences as much as to statistics and statutes. In the intricate cross-stitches and infinite possibilities of craft, there lies a profound truth: another world is possible, and we can make it with our own hands. Each of us holds a needle; together, we are stitching the story of tomorrow.