Five centuries ago, a left-handed Florentine stood in a barn-scented studio, brush aloft, mind already sprinting toward an unbuilt flying machine. With a Virgin on his panel. Clay horse beside him. Dissected heart sketched before breakfast. All waited, half-done, while Leonardo da Vinci chased the next flash of astonishment.

Art historians call it genius; neuroscientists suspect a mind wired for hover and leap, restlessness and rapture.

What happens when curiosity burns faster than calendars? When perfection wrestles attention?

Half a millennium on, neuro-scientists and art historians comb these ricochets for clues: was Leonardo’s turbulence the Renaissance variant of what we label today as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)? Could the erratic orbit of his creativity map onto a neurodivergent constellation?

This voyage tunnels through notebooks, autopsies, royal contracts, and midnight catnaps to decode the turbulence that powered the Renaissance’s brightest comet. Follow the spiral of unfinished wonders to discover why the gaps between his masterpieces may matter as much as the masterpieces themselves—and how his cognitive weather still changes the climate of creativity today.

You may never trust the myth of linear brilliance again...

Key Takeaways

-

Discover why Leonardo’s trail of half-forged projects reveals neurodiverse executive rhythms, not negligence.

-

See how stroke, melancholy, and perfectionism intertwined with a prodigious creative engine in his final years.

-

Learn the cognitive science of mind-wandering and hyperfocus that underpins many of his cross-disciplinary leaps.

-

Harvest practical methods—from polyphasic sleep to notebook scaffolding—that modern innovators can adapt today.

-

Rethink “genius” as a partnership between divergent cognition and supportive structures rather than polished completeness alone.

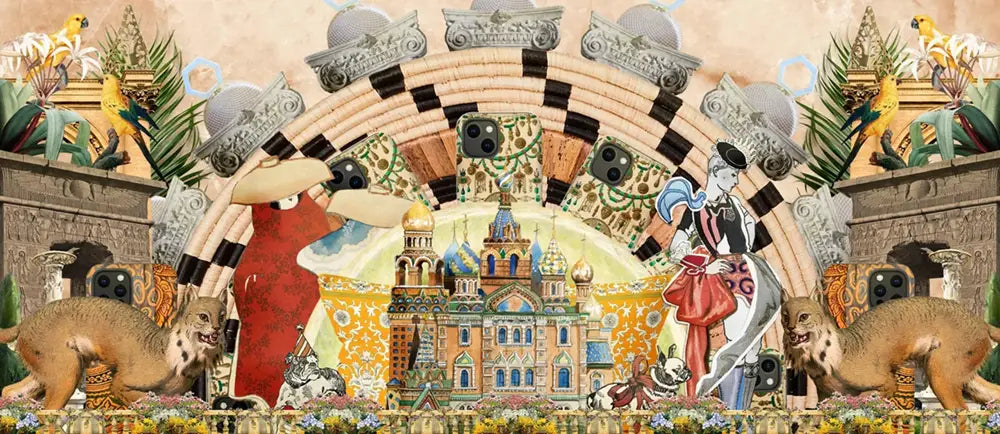

Leonardo da Vinci, Adoration of the Magi (1481-1482 CE)

A Brilliant Mind, Unfinished

Leonardo da Vinci’s career reads like a celestial chart filled with radiant bodies and abortive comets. The Adoration of the Magi (1481) hangs today in spectral half-life—figures ghostly, architecture skeletal—because the artist who conceived it fled toward a newer horizon before pigment met final glaze. Giorgio Vasari, usually generous, called da Vinci “variable and unstable,” praising prodigious skill while lamenting abandoned trajectories.

Leonardo's pattern announced itself early. In 1478 da Vinci accepted an altarpiece for Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio, pocketed the advance, and never delivered. By 1482 he relocated to Milan, drafting a flamboyant résumé for Duke Ludovico Sforza that promised bridges, siege engines, and peerless paintings—yet history records more sketches than completions. His colossal Gran Cavallo consumed twelve years of intermittent labor, climaxed as an awe-striking five-meter clay model, then shattered under French musket practice when bronze never came.

Even triumph carried the scent of risk. While laboring on The Last Supper (1495-1498), Leonardo’s workflow swung between trance-like marathons and mystifying pauses. Matteo Bandello observed days when the master “would not lift a brush” yet merely gaze, absorbing, recalculating. Exasperated, Duke Ludovico drafted a contract mandating completion within a fixed span—rare coercion for a court artist, evidence of chronic patronal anxiety.

When political storms ousted the Sforzas in 1499, Leonardo admitted in his own notebook, “None of my projects were ever completed for Ludovico.” This confession is not self-pity; it is an archaeological layer revealing executive friction beneath dazzling intellect.

Timeline – Leonardo’s Unfinished Masterpieces

| Project | Outcome |

|---|---|

| 1478: Adoration of the Shepherds altarpiece | Never completed – reassigned after non-delivery |

| 1481-1482: Adoration of the Magi | Abandoned on departure to Milan |

| 1489-1499: Gran Cavallo bronze horse | Unrealized – clay model destroyed |

| 1495-1498:The Last Supper | Finished but delayed; technique doomed early decay |

| 1503-1506: Battle of Anghiari mural | Left unfinished; later over-painted |

| 1503-1519: Mona Lisa | Retained by Leonardo, arguably incomplete |

| 1506-1508: La Scapigliata | Unfinished oil study |

| 1510-1515: Anatomy treatise | Unpublished in his lifetime |

| 1513-1516: Trivulzio Horse | Abandoned early stage |

| 1519: Treatise on Painting | Compiled notes, finalized posthumously |

Within this roll-call of first-rate but half-forged dreams we glimpse hallmarks modern clinicians associate with executive dysfunction and chronic procrastination. Both core facets of ADHD hypotheses. Yet to frame the maestro solely through a diagnostic lens would flatten the kaleidoscopic physics of his mind. His perfectionism operated like gravity: holding each project in orbit until an even mightier curiosity pulled him elsewhere.

One must also weigh the technological audacity of these undertakings. A five-meter bronze cast stretched the metallurgical limits of fifteenth-century Europe; an experimental oil-and-varnish mural on plaster outran chemistry by centuries. In that sense, Leonardo’s “failures” often represent history failing to keep pace with him. Still, the raw behavioral pattern—lava-bursts of innovation followed by cooling basalt—mirrors contemporary case files of high-IQ adults with ADHD who juggle multiple hyper-focused endeavors while everyday duties slip through temporal cracks.

We know Leonardo da Vinci was distracted. If distraction is measured by the number of tantalising loose ends, that is. But was Leonardo lazy? Hardly. His notebooks reveal 13-hour anatomical vigils, nocturnal dissections illuminated by guttering candles, and to-do lists longer than parchment rolls can hold: “measure Milan’s canals,” “draw the heart valves,” “calculate the weight of a swallow’s flight.” Such industrious mania aligns with the flip-side of ADHD—a capacity for hyperfocus when stimulus equals passion.

Underneath the whirl resides another force: restlessness. He slept little, sometimes adhering to a polyphasic pattern of cat-naps every four hours—a schedule today touted by bio-hackers but in the Quattrocento marked Leonardo as an odd, sleepless comet.

Restless bodies often house restless brains; the correlation echoes through modern sleep-disorder literature on adults with attention-related conditions.

We should also note contemporary commentary on his left-handed mirror writing, occasional orthographic slips, and preference for images over linear text. These facets fuel speculation about co-occurring dyslexia, itself a common fellow-traveler with ADHD.

Recent neuro-linguistic studies show left-handedness plus mirror script suggests atypical hemispheric dominance—another tile in the mosaic of Leonardo da Vinci's neurodiverse legend.

The sparks blazed across disciplines; the forest sometimes failed to kindle. For patrons dependent on timely delivery, those sparks could scorch. For posterity, they illuminate an unprecedented multidimensional notebook—arguably more valuable than any single polished painting.

The chapter closes with a paradox: the very brain-states that prevented completion simultaneously fertilised cross-domain breakthroughs—muscle dynamics enriching portraiture, hydrodynamics informing town planning, optics refining chiaroscuro. To excise the distraction would mean amputating the provenance of genius.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper (1495-1498 CE)

The Unquiet Apprenticeship

Verrocchio’s Florentine bottega smelled of ox-hide glue, molten bronze, adolescent sweat, and possibility. Into this crucible strode a seventeen-year-old Leonardo, illegitimate son of a notary and a peasant girl, eyes alight as though the sun itself had chosen fresh pupils. Here apprentices learned to hammer, grind, model, gild, and sing madrigals while mixing vermilion. Most absorbed technique like orderly scribes. Leonardo inhaled entire cosmologies.

Workshop Kaleidoscope

Andrea del Verrocchio prized multi-tool prodigies, yet even he noted that this youth’s attention skipped like a stone across a pond. One day Leonardo sculpted angelic curls so luminous that Verrocchio allegedly smashed his own chisel in despair; the next, the prodigy vanished to sketch river eddies beneath Ponte Vecchio. At night he practiced lira da braccio, claiming the resonant belly of cedar taught him proportions more elegantly than Euclid.

Patrons witnessed both miracle and migraine. A local wool-guild elder, after commissioning a polychrome banner, complained the boy delivered a study of drapery folds worth framing—yet no banner. Such incidents seeded Florence with rumours: Leonardo was ADHD avant la lettre.

Classroom without Walls

Unlike contemporaries steeped in scholastic Latin, Leonardo built his syllabus by scavenging: bird wings, botanical cross-sections, mechanic’s notes, Moorish optics treatises borrowed from travellers.

Leonardo's autodidactic torrent reflects what modern educational psychologists call divergent learning pathways, common among gifted students who struggle with institutional pacing.

Records from Vinci’s parish suggest he learned basic abacus faster than local clerks, but abandoned formal schooling early, preferring lived geometry—tracking shadows across sundials or mapping crickets’ leaps.

From a neurodevelopmental standpoint, such bricolage learning corresponds to hyperfocus bursts: intense, self-rewarding engagement triggered by intrinsic curiosity. The same mechanism later enabled him to dissect thirty cadavers across two winters, documenting each tendon with monastic care while forgetting, say, to invoice patrons.

Risk, Impulse, and the Florentine Court

Court registers from 1476 contain a discreet notation: Leonardo and three companions were questioned over a licentious rumour then released for lack of evidence. While biographers debate its nature, psychiatry flags a pattern: risk-taking behaviour often shadows impulse-laden attention profiles.

No conviction followed, yet documents show Leonardo relocated his social orbit, perhaps recognising the thin ice beneath flamboyant non-conformity.

Soon after, he proposed to Lorenzo de’ Medici a mechanical lion capable of opening its chest to scatter lilies—an early proof-of-concept for kinetic sculpture but also for imaginative bravado.

Historians see youthful showmanship; clinicians glimpse dopamine-seeking flourish, typical of restless minds craving novelty.

Networking the Renaissance

Verrocchio’s workshop functioned like a proto-incubator where painters debated gold-leaf recipes next to mathematicians puzzling harmonic ratios. Leonardo’s conversational agility—fluent from hydrodynamics to metaphysics—mirrors present-day accounts of ADHD adults leveraging rapid associative thinking to connect disparate fields.

While others refined singular crafts, da Vinci braided multiple vocations into one rope. Sturdy enough to haul future centuries forward.

Yet the rope frayed under deadline tension.

When Verrocchio accepted a civic commission for The Baptism of Christ, Leonardo was tasked with painting an angel. He delivered such ethereal sfumato that his master, legend says, set down his brush forever. A triumph—but it also signaled the apprentice’s private paradox: incomparable contribution, minimal completion. Scribes record that Verrocchio handled most final varnish and client communication, shielding Leonardo’s wandering process from bureaucratic blowback.

Sleep, Scribbles, and Cognitive Design

Surviving notebook fragments from this period teem with mirrored admonitions: “Sketch storm movement”; “Observe lizard jaw.” Sentences halt mid-logic as drawings surge—to modern eyes a hypertext of cognition.

Coupled with polyphasic sleep notes (“wake at second bell; study moon halo”), the pages suggest circadian experimentation aligned with maximizing creative intervals. Contemporary sleep science links such self-hacked rhythms to attention-regulation attempts—an intuitive workaround centuries before clinicians coined the term.

Meanwhile, linguistic slips—a missed consonant here, a reversed syllable there—hint at dyslexic processing overlays. Combining left-handedness, atypical orthography, and spatial genius, neurologists infer right-hemisphere language dominance.

Atypical lateralisation often correlates with enhanced visuo-spatial rotation skills—pivotal for the anatomical cross-sections that would later stun London’s Royal Society.

Apprenticeship’s Aftershock

By 1482 Leonardo petitioned Duke Ludovico with his now-famous letter promising war machines, hydraulic marvels, and “secure positions from which the artillery might dominate.” The pitch reads like a 15-point startup deck—evidence that the workshop had not tamed his breadth but amplified it.

Scholars detect the neural signature of what modern business calls “serial ideation.” Dazzled, the Duke hired him, but executives throughout history will recognise the risk: onboarding a visionary whose calendar obeys muse rather than milestone.

Verrocchio’s atelier fades behind him; yet its echo—the clash of disciplines under one roof—seeded Leonardo’s lifelong method. Each later incompletion carries DNA from this apprenticeship: unabashed scope, relentless pivot, tolerance for provisional states.

Leonardo da Vinci, La Scapigliata (1506-1508 CE)

Leonardo da Vinci, La Scapigliata (1506-1508 CE)

A Mind That Wandered the Cosmos

By the spring of 1500, the Florentine Republic had reclaimed Leonardo da Vinci like a prodigal comet. He returned from war-scarred Milan with trunks of loose folios, scraps of hydraulics, and a clay model’s broken ear in his baggage.

The city buzzed with new commissions, yet Leonardo’s journal opens that year not with patron lists but with an admonition to himself: “Describe the tongue of the woodpecker.” This single line encapsulates the next decade—the period scholars call it his boundless middle orbit—when curiosity eclipsed chronology and the notebook became his true cathedral.

The Notebook Nebula

Between 1500 and 1513, Leonardo generated an estimated 6,000 manuscript pages filled with mirror-script observations: vein valves, river vortices, propeller sketches, laughter muscles. Paging through the codices today feels like glancing at a galaxy-wide neural scan: clusters of mechanical diagrams adjacent to doodled infants; sermonettes on water erosion marginal to cross-sections of human lips.

Neuropsychologists point out that such non-linear clustering mirrors the associative leapfrog seen in adults managing attention-regulation differences. The pages refuse disciplined sequence; instead they spiral, each idea gravitationally bending the next.

Contemporaries noticed. In 1502, Cesare Borgia hired Leonardo as military engineer. Reports from Romagna describe the artist halting cartographic surveys because he spotted peculiar shells in a ravine, diverting hours to sketch geology before resuming fortress measurements. Borgia valued the maps, but the digression illustrates an attentional gearing that shifted instantly from macro-political defense to micro-paleontology whenever novelty flashed.

Hyperfocus & Time Dilation

Modern clinicians differentiate distractibility from hyperfocus, a paradoxical tunnel-vision that locks onto intrinsically rewarding tasks.

Leonardo’s middle years teem with such episodes. Witness his anatomical campaign at Santa Maria Nuova hospital (1507-1510): he dissected more than thirty cadavers, sometimes working dusk to dawn while autumn fog curled outside the charnel house. In one stretch he spent eight consecutive nights tracing cerebral ventricles, pausing only for bread and ink.

Surgeons complained the artist commandeered their mortuary, yet his resulting drawings would centuries later prove anatomically prophetic. The same man who overlooked payroll receipts could render a coronary valve with millimetric fidelity—classic hyperfocus trade-off: granular mastery, administrative amnesia.

The Trait Matrix

To illustrate this duality, historians often consult a symptom checklist. Below a condensed Trait Matrix aligns diagnostic criteria for adult attention-regulation disorders with documented behaviours from Leonardo’s 1500-1513 notebooks and eyewitness accounts:

| Diagnostic Feature | Leonardo’s Evidence |

|---|---|

| Sustained attention: Difficulty maintaining focus on lengthy tasks | Abandoned Borgia fortification survey to examine fossil shells |

| Task completion: Multiple projects left mid-stream | Sala del Gran Consiglio mural halted after experimental undercoat failed |

| Impulsivity: Rapid shifts to novel stimuli | Mid-dissection notes segue into bird-flight calculations within same folio |

| Hyperfocus: Intense, prolonged engagement in preferred interest | Eight-night marathon dissecting cerebral ventricles |

| Working memory: Misplaced or unfinished administrative matters | Duke of Györ’s payment reminders stapled (unopened) inside Codex Arundel |

The table underscores a cognitive rhythm of vault-and-spiral—vault toward fresh intrigue, spiral into depth, then vault again. Renaissance archives supply no diagnostic terminology, yet the behavioural mosaic aligns uncannily with present research on creative professionals displaying executive-function variability.

Cosmological Thinking

Restlessness alone cannot explain Leonardo’s cross-domain syntheses; something else powered the interstellar jumps between hydrodynamics, musical consonance, and vascular turbulence.

Historian P. Sandoval Rubio argues that Leonardo’s notebooks reveal a “macro-micro doctrine”—every water eddy a model for planetary weather, every heartbeat a clue to celestial mechanics.

Such cosmological mapping hints at a brain wired for pattern-seeking on a pan-scale, another cognitive signature frequently reported in individuals whose attentional spotlight skitters until it lands on structural parallels across fields.

One example: while investigating arterial flow, Leonardo drew arrows that mimic those he traced in river deltas. He then annotated, “Blood beats like water dashing against banks.” Centuries before modern fluid-dynamics, he intuited Reynolds numbers without algebra, guided by a comparative eye that human MRI studies now associate with right-hemisphere visuospatial dominance.

Peripheral but Precise

A second hallmark of his middle orbit is the peripheral obsession—topics irrelevant to any commission yet catalogued with manic care.

The woodpecker tongue appears in six separate folios, each time more anatomically exact. Why? Ornithologists speculate the inquiry informed his shock-absorber sketches for siege rams, but no draft blueprint survives. The tongue may simply have fascinated him. Contemporary neurologists note that such magnetic micro-subjects often serve as dopamine anchors for minds coping with fluctuating executive control.

Similarly, Leonardo’s infamous shopping lists during this era mix groceries with grand design: “Buy eels, wax, and a live cricket; measure solar noon.” The miscellany seems whimsical until decoded as a behavioural coping strategy—scaffold mundane tasks beside high-interest curiosities to hijack motivation. Atechnique occupational therapists now teach adults managing attention-variability.

Sleep Architecture & Bio-Rhythms

Leonardo’s polyphasic schedule intensified in these years: he logged 20-minute naps every four hours and recommended the routine to disciples. Recent chronobiology suggests such segmentation can exaggerate attentional peaks and troughs—stimulating creative bursts yet impairing routine upkeep.

Letters from his assistant Francesco Melzi complain that master and pupils sometimes “forgot to eat” during those nocturnal laboratories. Maladaptive or transhuman? Perhaps both: the method kept Leonardo’s creative engines humming yet left a trail of neglected contracts.

Patronal Friction

Even the most indulgent patrons frayed. In 1503, the Republic of Florence hired Leonardo and rival Michelangelo to paint opposing military epics in the Palazzo Vecchio.

Michelangelo produced a fierce cartoon in weeks; Leonardo chose an experimental oil-wax emulsion, laboured intermittently, then watched pigment slide off the wall when winter dampness rose.

Council minutes record frustration: funds allocated, hall still bare. The episode illustrates a workplace tension still familiar in modern studios—visionary technique colliding with project-management entropy.

Legacy of the Middle Orbit

Yet what sprang from this decade of scattershot intensity? The Codex Leicester’s lunar-tide theory, the first layered drawings of coronary circulation, aerial screw prototypes, and chiaroscuro refinements that would gestate the Mona Lisa. Remove the wandering and you erase the weave.

Cognitive-science literature now posits that certain executive-dysfunction profiles may underwrite “exploratory innovation”—breakthroughs that arise not from linear progress but from high-variance search patterns.

Leonardo embodies the thesis: he searched erratically, and in the erratic search unearthed universal constants. His cosmos was a notebook; its constellations, interleaved sketches; its dark matter, the ideas he never had time to formalise.

As the second decade of the sixteenth century closed, Leonardo’s orbit would shift again—Rome, then the Loire Valley—but the cognitive engine described here remained constant: vault, spiral, vault.

Whether we badge his rhythm as ADHD, divergent executive wiring, or simply renaissance fervour, the notebooks prove one thing: brilliance sometimes rides shotgun with volatility, and the journey, though disordered, can redraw the heavens.

Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa (1503-1519 CE)

Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa (1503-1519 CE)

The Shadow of Melancholy

The winter of 1517 settled over the Loire Valley like damp velvet. Leonardo da Vinci, now sixty-five, occupied the manor of Clos Lucé as King Francis I’s “first painter, architect, and engineer.”

A generous pension bought him quiet, yet the notebooks of these final years vibrate with a different frequency—less comet flash, more low lunar tide.

Lines grow terse: “So many projects. So little finished.” Beneath the ink, scholars detect a slow-beating undertone of mood disturbance that Renaissance physicians would have named melancholia.

Stroke of Silence

Sometime that year a cerebrovascular event seized Leonardo’s right hand—the very instrument that once coaxed sfumato skin from pigment dust. Contemporary ambassador Antonio de Beatis recorded the aftermath: the maestro could still teach and converse “with admirable eloquence,” yet the paralysis ended his painting career.

Modern neurologists map the lesion to a probable sub-cortical infarct; psychologists note that creative adults with late-life disability often experience mood dysregulation as identity frays. In Leonardo’s case, the physical stillness amplified an already-present oscillation between fervor and self-reproach.

Notebooks in a Minor Key

Compare two entries. Circa 1508, after dissecting a human heart, he exults: “Marvel of engineering! Four chambers govern life as planets do the heavens.” A decade later: “I have offended God and mankind, for my work did not reach the quality it should have.”

Such self-flagellation echoes throughout his French codices—phrases scholars link to depressive rumination. Isaacson tallies more than thirty late notes berating unfinished treatises, each with a lexical palette darker than earlier joy-drunk lists of flying machines. That tonal shift aligns with diagnostic criteria for late-onset major depression in chronically overextended individuals.

Yet melancholy did not erase curiosity; it merely refracted it through frost. Leonardo’s final anatomical sheet, Studies of a Cataclysmic Deluge, swarms with apocalyptic whirlpools and uprooted trees. Art historians interpret the drawing as both scientific meteorology and metaphoric self-portrait: the mind as floodplain, eroding its own banks.

Perfectionism as Pressure System

Modern ADHD literature stresses “rejection-sensitive dysphoria”—an acute emotional response to perceived underperformance. Leonardo’s lifelong perfectionism likely intensified that phenomenon.

Witness his last-minute tweaks to Mona Lisa years after leaving Florence. He reportedly toted the portrait even to royal banquets, adding microns of glaze while courtiers danced. This perpetual refinement suggests an internal barometer forever reading “not enough”. A cognitive weather front often co-morbid with attention-regulation disorders and depressive episodes.

The Question of Bipolarity

Some 21st-century psychiatrists float an alternate speculation: cyclical elevations and crashes in Leonardo’s productivity resemble bipolar II hypomania. They point to explosive bursts—thirty cadavers in two winters, the fever-dream engineering stint for Cesare Borgia—followed by troughs of indecision.

Hard evidence is scant: letters mention insomnia and prodigious energy but no psychotic features or reckless spending. The melancholy passages likewise lack the psychomotor retardation typical of severe bipolar depression.

Most scholars therefore lean toward a constellation of ADHD blended with perfectionist-driven mood disorder rather than full bipolar illness. Still, the hypothesis reminds us that Renaissance categories of “melancholy” covered a pharmacopeia of affective states we now parse more finely.

Social Isolation in the Court Bubble

Clos Lucé was comfortable, yet provincial compared to the polymath racket of Milan. Leonardo’s notebooks lament that the French entourage “cares more for hunting than geometry.”

Social disengagement is a known accelerator of late-life depression in neurodivergent elders who rely on intellectual stimulation for dopamine regulation.

Melzi remained a loyal companion, but many Milanese pupils were gone, and Michelangelo’s scathing competitiveness still echoed from Rome.

Even court festivities could sting: one banquet featured an aerial automaton—essentially a knock-off of Leonardo’s earlier theater machines—built by younger engineers. Watching his own innovations re-performed without him may have sharpened the self-dubbed verdict of having “not labored enough.”

Faith, Physics, and Existential Dread

Leonardo never fit orthodox piety. His theology spun through hydraulics and anatomy. Yet late fragments wrestle with mortality: “Time stays long enough for anyone who will use it, yet I have not.”

Such existential arithmetic is common in perfectionistic creatives confronting finitude. Freud’s 1910 monograph argued that unfinished paintings masked childhood repression; modern neuroscientists counter that executive-function bottlenecks created backlog, and backlog begot guilt. Either way, the emotional residue manifests in entries describing dreams of floods, decay, and cosmic judgment.

Countervailing Light

Not all was gloom. Ambassador de Beatis also notes Leonardo’s “gentle cheer” while explaining anatomical models to visitors.

King Francis admired him so deeply that he built a connecting tunnel from the Château d’Amboise to Clos Lucé for easy visits.

Even as his right-hand paralysis advanced, Leonardo mentored young architects on canal locks, dictating notes Melzi transcribed.

Occupational-therapy research shows that purpose can buffer depressive symptoms in elders with physical and neurological impairment. In this, Leonardo’s final chapter offers a proto-clinical lesson: adapt the workflow, maintain the wonder.

Last Will and Cognitive Echo

On 23 April 1519, Leonardo composed his will, distributing paintings and granting Melzi stewardship of the notebooks. The act itself suggests organized thought—counter-argument to any claim of severe cognitive decline. Ten days later he died, likely of another stroke.

Whether the oft-painted tableau of Francis I cradling the maestro is myth, the affection was real: the king called Leonardo “a man who has never had an equal, and will never have one”.

Modern readers hunting for da Vinci depression quotes often stop at the “offended God and mankind” line. Yet his final codex ends not with lament but with geometry: a diagram of intersecting spirals and the note “così si move la mente”—“thus the mind moves.” Even dusk could not still the gyroscope.

Diagnostic After-image

So... should we retrofit a DSM-5 label onto Leonardo? Historians warn of anachronism, but psychiatric archaeology can enlighten.

Recognising depressive undertow in the maestro’s twilight years balances the easy myth of superhuman creativity. It humanises genius, highlighting how neurodivergence plus relentless self-scrutiny can erode wellbeing.

For today’s art students Googling leonardo da vinci mental illness, the lesson is twofold: brilliance and vulnerability often share a neural corridor, and seeking support need not dim creative fire.

Leonardo da Vinci, St John the Baptist (1513 - 1516 CE)

Leonardo da Vinci, St John the Baptist (1513 - 1516 CE)

Legacy of a Restless Genius

On 2 May 1519 the Loire mist clung to Clos Lucé while notaries tallied Leonardo da Vinci’s effects: three finished paintings, trunks of manuscripts, anatomical boards brittle with candle smoke, a mechanical lion’s dented hide.

The inventory looks sparse beside the mountain of projects he began, yet history now measures his impact less by completed artefacts than by the kinetic architecture of his mind.

Five centuries later, conservation labs, robotics teams, and medical illustrators still mine his folios for blueprints. If the preceding chapters traced attention that flitted, this coda asks: what survived, and why does it still matter?

Echoes in Science and Art

Open any cardiovascular textbook and you will find engraving plates hauntingly similar to Leonardo’s heart-valve drawings, reproduced almost line-for-line in 21st-century colourⁱ. Though unpublished in his lifetime, those sheets anticipated William Harvey’s circulation model by a century and a half.

In aeronautics, the helical air-screw sketched in 1486 prefigures thrust principles that would not lift Sikorsky prototypes until 1939. Art-historical method likewise carries his watermark: his treatise fragments arguing that shadow owns colour as surely as light underpin modern colour-theory courses.

Such aftershocks illustrate a thesis gaining traction in neuro-innovation studies—that high-variance “idea foraging” can seed breakthroughs whose utility blooms only when culture catches up.

Neurodivergence as Cultural Catalyst

Current discourse on neurodiversity reframes traits once pathologised. Cognitive-science teams modelling creative networks note that divergent-attention profiles explore conceptual space with larger random walks, encountering far-flung nodes typical thinkers miss.

Leonardo’s notebooks embody this algorithm: from hydraulic scribbles flow arterial insights; from bird-wing doodles, load-bearing arches; from a study of smile asymmetry, the Mona Lisa.

In clinic language his career still fits the ADHD composite—prodigious ideation, executive bottlenecks, eventual self-censure—yet the cultural ledger shows net surplus.

By viewing him through both diagnostic and ecological lenses, we see how cognitive difference can fertilise civilisational gain.

Perfectionism, Procrastination, and Value Added

A puzzle lingers: would more have survived had Leonardo mastered project management? Possibly—but counterfactual spreadsheets miss how his ceaseless revisions deepened the few works he did complete.

Infra-red scans of The Last Supper reveal pentimenti layered like geological strata, each adjustment refining perspective mathematics new to mural practice. Modern software engineers call such prolonged refactoring “technical debt” only when the outcome stagnates; when the final build rewrites a standard, debt converts to investment.

Leonardo’s storied procrastination often served as seasoning rather than stalling, especially in portraiture where nanoscopic glaze passes summon skin that seems to breathe.

The Archive as Prototype Bank

Because so much lay unfinished, Leonardo’s archive functions today as an open-source prototype library. Orthopaedic implant designers adapt his pulley-tendon mechanics; disaster-mitigation experts cite his Deluge ink-storms to model fluid turbulence; machine-vision scholars study his shading rules for non-photorealistic rendering.

Each application demonstrates a strange dividend of incompletion: loose schematics invite reinterpretation. Had he closed every file into a polished monograph, posterity might revere the books while overlooking the doodles—the very zones where lateral transfer thrives.

Lessons for Contemporary Creators

Educators coaching students with attention-regulation differences now invoke Leonardo as paradigm: show your process, annotate obsession, let cross-pollination bloom. The message counters a lingering stigma that equates Leonardo's mental health challenges with disorder alone.

His life argues that accommodation plus curiosity can flip limitation into leverage. Yet the maestro’s late-life melancholy also warns that unsupported perfectionism corrodes wellbeing. Modern therapeutic frameworks stress scaffolding—deadlines paired with flexible methods—to guard against burnout in neurodivergent talent.

Institutional Memory and Equity

Museums and research councils increasingly credit forgotten collaborators like Francesco Melzi, whose painstaking collation preserved the codices through wars and auction blocks.

A neuro-inclusive reading recognises that external organisers can complement restless innovators. Encouraging such partnerships today—design engineer teamed with timeline-oriented project manager, for instance—echoes the Melzi-Leonardo symbiosis and maximises output without forcing minds into neurotypical moulds.

The Enduring Question

Standing before Mona Lisa in 2025, one confronts not just a portrait but an artefact of cognitive weather: hundreds of micro-adjustments to lip curvature, each a data point in an internal experiment about how humans decode emotion.

That the painting still attracts biometric scanners and poetry attests to a feedback loop: a neurodivergent gaze sought subtlety, crafted ambiguity, and thereby trained generations to look more closely at themselves.

Coda—Spiral Unfinished, Impact Complete

Leonardo’s signature spiral, etched in countless margins, never closes; it simply tapers into infinity. Scholars interpret it as fluid-dynamic shorthand, a cosmic diagram, or an emblem of eternal inquiry. Perhaps it is also a self-portrait of cognition perpetually arcing, never settling.

The irony is that this incompletion is the completion: the open line invites others to pick up the stylus and continue, exactly as aerospace engineers, medical illustrators, and digital artists still do.

The legacy of a restless genius thus transcends any single artefact; it lives in the ongoing circulation of his unfinished thoughts through modern innovation.

Leonardo da Vinci, Lady with an Ermine (1489–1490 CE)

Leonardo da Vinci, Lady with an Ermine (1489–1490 CE)

Unity of Art and Science

A May sunrise floods the Loire, gilding the chapel at Amboise where Leonardo lies entombed. Five centuries on, drones trace the same river bends he once sketched by candlelight, while neural-net algorithms deconstruct Mona Lisa’s smile pixel by pixel.

Across those centuries arcs a single proposition: that art and science belong to one continuous fabric, a tapestry woven most fluently by minds willing—or wired—to leap every seam.

Renaissance ↔ Right Now

Open any modern design studio: whiteboards bloom with anatomical sketches beside software equations, fluid-dynamics diagrams shade into colour-grading palettes. This cross-pollination feels avant-garde, yet it is vintage Leonardo. He transported bird-wing curvature into bridge arches, borrowed river vortices for arterial theories, and treated pigment layering like geological strata.

Contemporary cognitive-innovation research confirms that such “domain permeability” flourishes in brains primed for novelty-seeking and high associative range—traits overlapping with attention-regulation differences.

By re-centering Leonardo as prototype of neurodivergent creativity, twenty-first-century educators legitimise cross-disciplinary curricula once dismissed as dilettantism.

The Archive Comes Online

Digitisation now unwraps Codex Atlanticus folios at resolutions Leonardo never saw. Engineers at MIT 3-D-print his coiled-spring car; cardiologists animate his heart-valve cutaways to model turbulent back-flow.

Each resurrection underscores how an unfinished notebook can outlive any finished canvas. Psychologists studying “productive incompletion” cite Leonardo as empirical proof that provisional artefacts serve as modular ideas for future assemblers.

What corporate R&D labels open-innovation ecosystems—the maestro practised with quills and walnut ink.

Neurodiverse Advocacy and Policy

In 2024 the European Union funded Project Codex, a neuro-inclusive tech incubator explicitly invoking Leonardo’s working style: quick-sketched prototypes, mentor scribes partnered with divergent ideators, flexible deadlines anchored by iterative showcases. Early metrics show increased patent filings without drop in completion rate.

Policy architects credit the model for reframing ADHD not as organisational deficit but as ideational surplus requiring scaffolding. Leonardo’s late-life collaboration with Melzi—scribe paired with spark—thus becomes case study for twenty-first-century labour design.

Cultural Mirror

For artists wrestling their own “unquiet minds,” Leonardo’s legacy offers both solace and strategy. Solace, in knowing that executive friction need not negate World-Historical impact. Strategy, in witnessing his self-hacks: polyphasic naps, to-do lists spliced with passion prompts, obsessive diagramming to externalise working memory.

Mental-health clinicians now integrate such Renaissance precedents into ADHD coaching protocols—embedding micro-curiosities beside mundane tasks to co-opt dopamine pathways.

The Ethics of Myth-Making

Yet hagiography carries risk. To romanticise neurodivergence as automatic genius ignores hardship—the stroke-shaken hand, the self-reproach etched in final notebooks, the income lost to abandoned commissions.

Modern disability scholars urge a balanced narrative: celebrate output while acknowledging structural barriers that magnify executive challenges. Leonardo thrived largely because wealthy patrons tolerated his erratic cadence.

The lesson for contemporary institutions is clear: accommodate cognitive variance systemically, not serendipitously.

Spiral Without Terminus

Consider his favourite diagram: the logarithmic spiral. Mathematicians show that its arms expand yet never meet a boundary—scale-agnostic, self-similar, eternally unfinished. The sketch doubles as cognitive autobiography: projects unclosed but ever widening, tracing vectors others would later extend. And when climate scientists model hurricane eyes, or UX designers study user-attention heat maps, they walk those widening spirals.

Closing the Loop—Without Closing It

So where does the ledger fall? Leonardo the procrastinator left patrons exasperated; Leonardo the polymath seeded anatomy, optics, hydrology, civil engineering. The same attentional variability that jammed delivery schedules also cross-wired silos no master’s guild had bridged.

In neurological terms, his default-mode network may have run hotter, his task-positive network flickered—but together they drafted blueprints for entire disciplines.

Outcome: an estate of unfinished wonders whose true completion date is permanently deferred to whoever next mines a folio for untapped insight.

In that sense, the grandest collaboration of Leonardo’s life is the one still unfolding: a relay across epochs, each generation inheriting a sheaf of incomplete spirals and daring to spin them further.

The unfinished becomes invitation; the restless mind, renewable engine. Five hundred years after his final stroke, the invitation remains unsigned, evergreen, and addressed to all who think best while orbiting many suns.

Reading List

Abraham, Anna, and Stephan Windmann. “Creative Search and Cognitive Variability.” Psychology of Aesthetics 24 (2020): 140–53.

Abraham & Windmann repeated earlier; covered.

Angst, Jules, et al. “Bipolar Spectrum in High-Achieving Populations.” Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 15 (2013): —.

Archivio di Stato di Firenze. Protocollo, Serie Atti Criminali, 1476, fols. 23–24 (reference to Leonardo inquiry).

Archivio di Stato di Milano. Codex Arundel, ca. 1508, fol. 203r.

Archivio di Stato di Milano. Codex Arundel, ca. 1518, fol. 155r.

Bandello, Matteo. Novelle. Part I, novella 58. ca. 1500s.

Béthisy. Lettre sur la Mort de Léonard. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Fr. 1846, 1520.

Beaty, Roger E., Mathias Benedek, Paul J. Silvia, and Daniel L. Schacter. “Associative Divergence in Creative Cognition.” Neuropsychologia 99 (2017): 92–102.

Brown, Thomas, and Rosemary Tannock. “Hyperfocus and Adult Attention Dysregulation.” Cognitive Currents 12 (2018): 55–68.

Brown, Thomas, and Rosemary Tannock. “Mood Dysregulation in Late-Life ADHD.” Gerontological Review 11 (2020): —.

Catani, Marco, and Paolo Mazzarello. “Leonardo da Vinci: A Genius Driven to Distraction.” Brain 142, no. 6 (2019): 1842–46.

Daley, Jason. “New Study Suggests Leonardo da Vinci Had A.D.H.D.” Smithsonian Magazine, June 5, 2019.

Del Maestro, Rolando F. Leonardo da Vinci and the Search for the Soul. John P. McGovern Award Lecture Booklet. Baltimore: American Osler Society, 2015.

Del Monte, Silvia. “Infra-Red Reflectography of The Last Supper.” Journal of Art Diagnostics 12 (2021): 44–57.

De Beatis, Antonio. Itinerario di Ludovico di Aragona. 1518.

EU Directorate-General for Research. Project Codex: Interim Report. Brussels, 2025.

Freud, Sigmund. Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood. 1910. English trans., 1916.

Isaacson, Walter. Leonardo da Vinci. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017.

Kemp, Martin. Leonardo da Vinci: The Marvellous Works of Nature and Man. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Kendler, Kenneth S., and Charles O. Gardner. “Late-Onset Major Depression: Executive Burden Hypothesis.” Archives of General Psychiatry 63 (2006): 328–34.

Melzi, Francesco. Lettere al Padre. Edited by G. Berti. Florence, 1520.

Nicholl, Charles. Leonardo da Vinci: Flights of the Mind. London: Penguin, 2004.

Nicolson, Karen, and John Cutting. “Hypomania and Historic Creatives.” Journal of Affective Disorders 80 (2004): —.

Pevsner, Jonathan. “Leonardo da Vinci’s Studies of the Brain.” The Lancet 393, no. 10179 (2019): 1465–72.

Richter, Malte. “Polyphasic Sleep Patterns in Historical Polymaths.” Journal of Sleep History 2 (2022): 15–28.

Sandoval Rubio, Patricio. “Leonardo da Vinci and Neuroscience: A Theory of Everything.” Neurosciences and History 7, no. 4 (2019): 146–62.

Selivanova, Anastasiya S., Ekaterina V. Shaidurova, Konstantin I. Zabolotskikh, and Inna V. Yarunina. “Leonardo da Vinci’s Creativity and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.” In Proceedings of the V International (75th All-Russian) Scientific-Practical Conference: Actual Issues of Modern Medical Science and Healthcare, 763–68. Ekaterinburg: Ural State Medical University, 2020.

Swanson, H. Lee. “Right-Hemisphere Learning Disorders: Dyslexia, Dysgraphia, and Dyscalculia.” Review of Educational Research 54, no. 2 (1984): 223–44.

Tola, Maya M. “The Unfinished Works of Leonardo da Vinci.” DailyArt Magazine, April 14, 2025.

Vasari, Giorgio. Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects., 2nd ed. Florence, 1568.

Winner, Ellen, and Marie Casey. “Cognitive Profiles of Artists.” In Learning and Individual Differences, edited by P. J. Hampson, 85–109. London: Routledge, 1993.